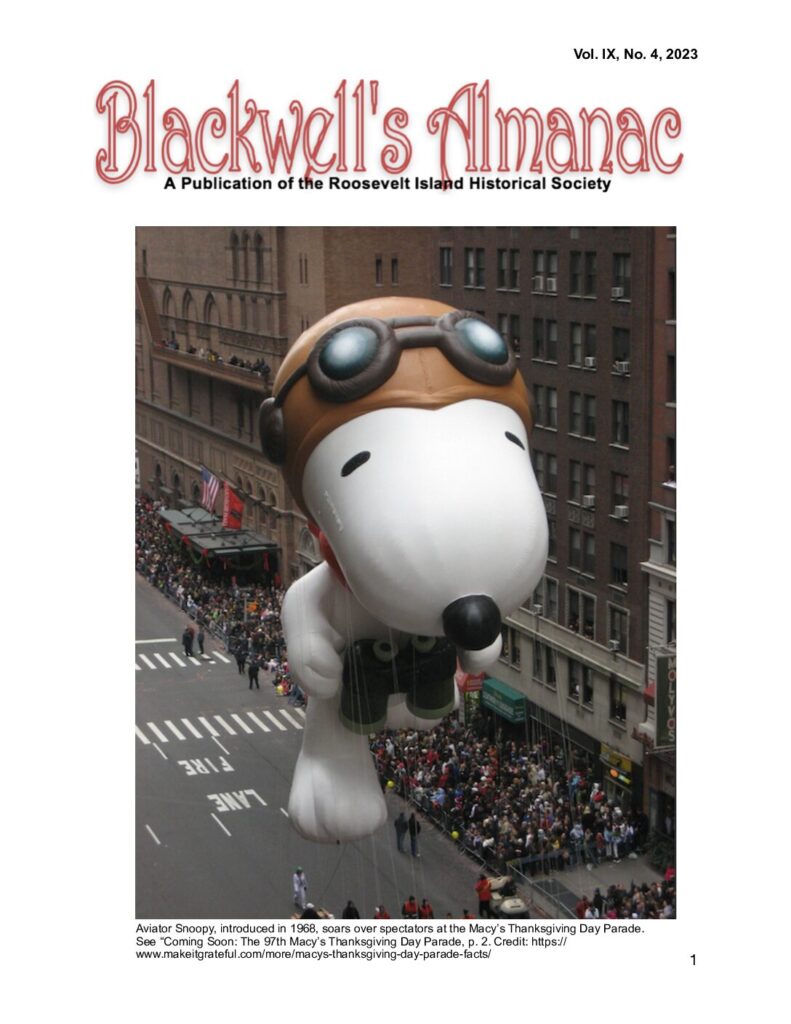

November Issue of Blackwell’s Almanac

Click the image below for the full text of the November Issue of Blackwell’s Almanac.

Nov

14

Oct

24

In 2015, Untapped New York writer Thomas Hynes asked a pressing question to a representative of the NYC Department of Environmental Protection. “Are there now or have there ever been alligators in the New York City sewer system?”

Legend has it that in the early 20th century, wealthy New Yorkers would vacation to warm states like Louisiana and Florida, bringing back with them baby alligators as souvenirs. Once these gators got bigger and their owners realized New York was not the appropriate home for them, they would be flushed down the toilet to live and reproduce in our city sewer system. Despite the response that came back from the Department denying any existence of sewer alligators, New Yorkers have remained fascinated with this mythical concept

Photo by Jane Kratochvil

The myth comes back to life with a new statue unveiled on Tuesday, October 17th; a life-sized bronze alligator perched on the back of a manhole lid. This piece of alligator art, titled NYC Legend, was crafted by Swedish artist Alexander Klingspor, famous for his gorgeous bronze work. A smaller version of the gator was displayed at the 2022 London Art Fair, only now having the full-sized piece unveiled in exactly the city where it belongs.

In Klingspor’s description of the sculpture, he says that it’s inspired by two themes he noticed in our world. The first is the fact that our civilization still very much needs gods and mythical creatures as did the humans that came before us. Our natural desire for the supernatural is simply not as visible as it once was, but it surely still exists in the backdrop (or sewers) of our daily lives. The second theme aims at exposing our modern habit of taking animals out of their natural environment and putting them where we see fit, creating an endless cycle of invasive species.

Photo by Jane Kratochvil

Alligators themselves have made themselves an integral part of mythology spanning thousands of years, symbolizing survival and the ability to regrow and adapt. New Yorkers have consistently proven they have the thick skin of a gator- through a pandemic, economic downfall, a terrorist attack, and beyond. Klingspor’s statue is a personification of this resilient New York spirit.

Alligator art sculpture in Union Square

At the Thompson Central Park New York, a short distance uptown from Union Square, there is a highly-anticipated public art exhibition featuring more of Klingspor’s work where visitors can also get a behind-the-scenes into the artist’s creative process of bringing NYC Legend to life. This exhibition will be on display within the hotel’s newly unveiled ground floor atrium through November. The alligator sculpture, NYC Legends, will be on display in Union Square’s Triangle Park through June 2024.

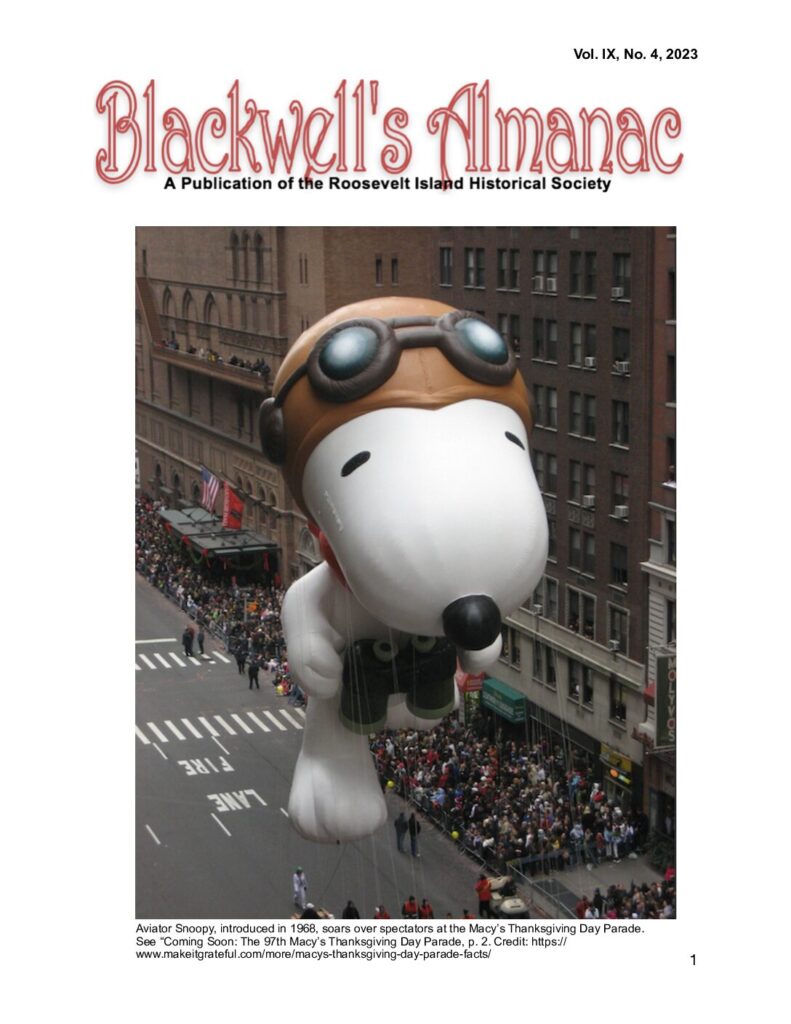

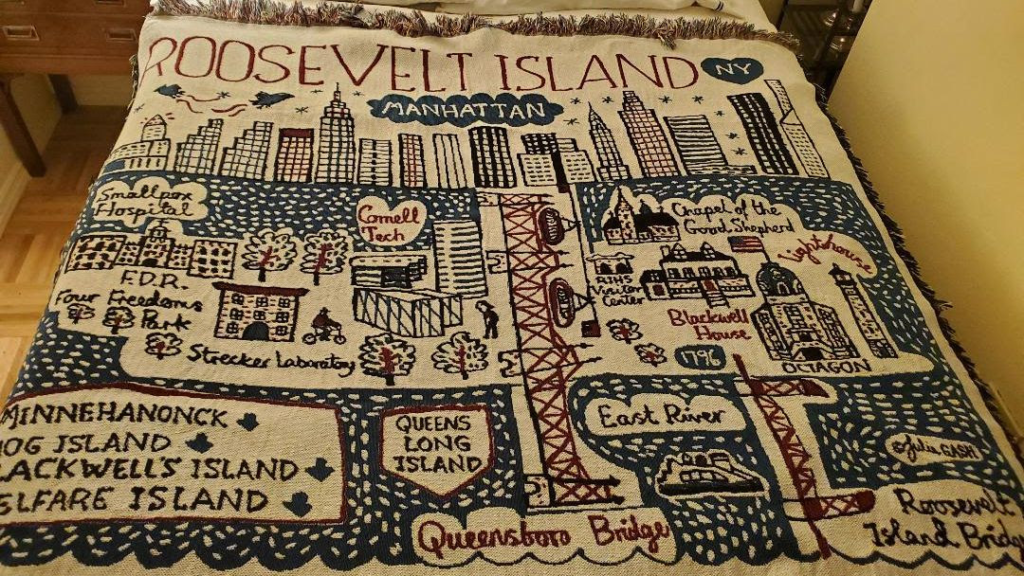

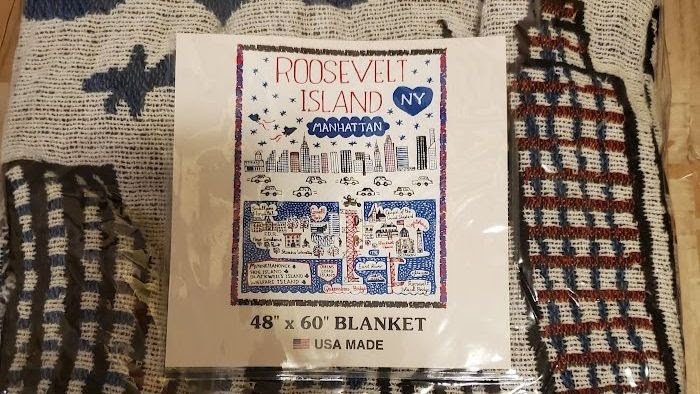

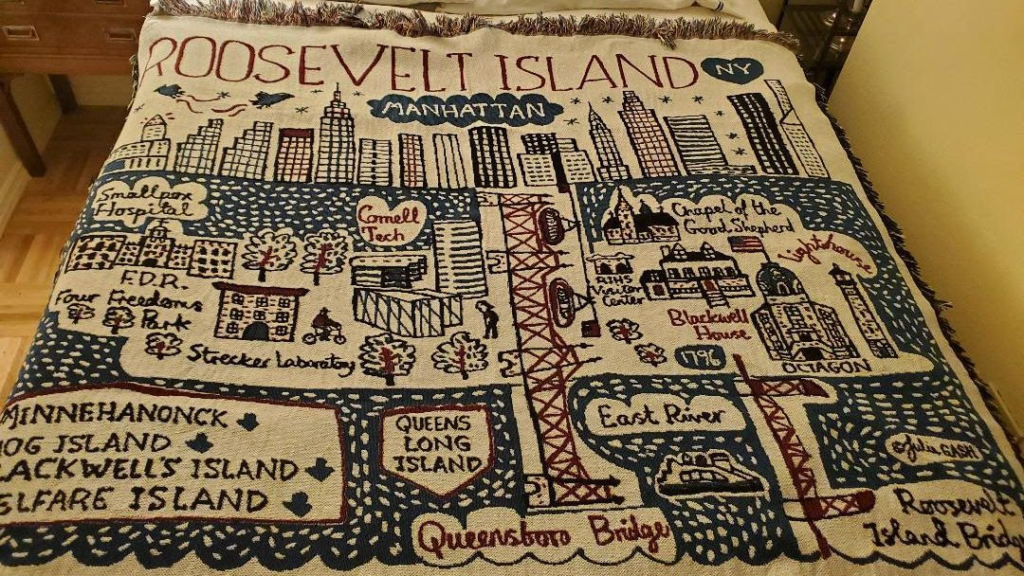

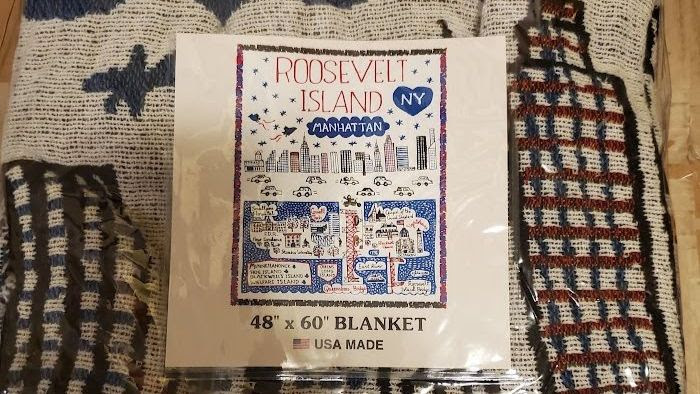

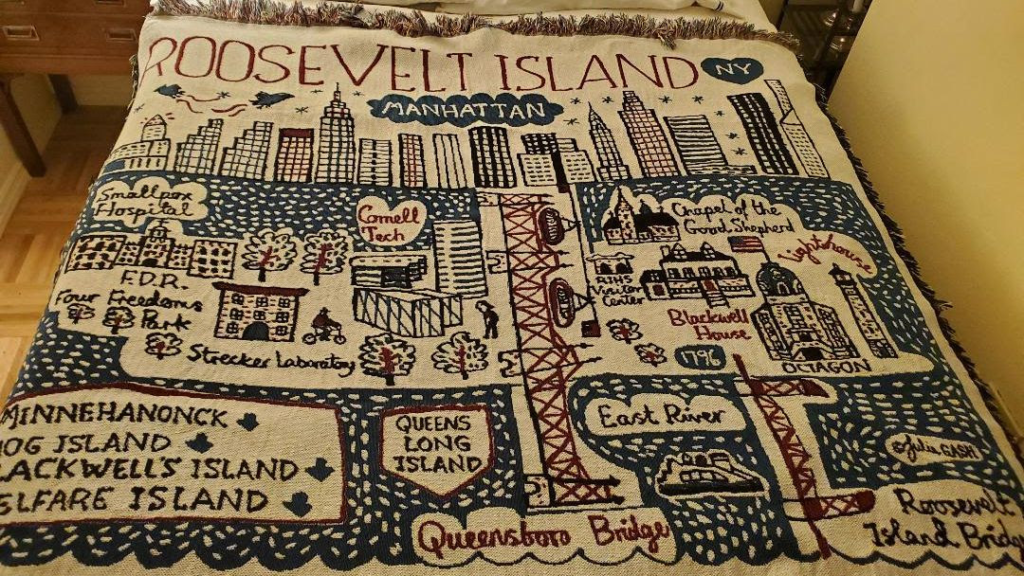

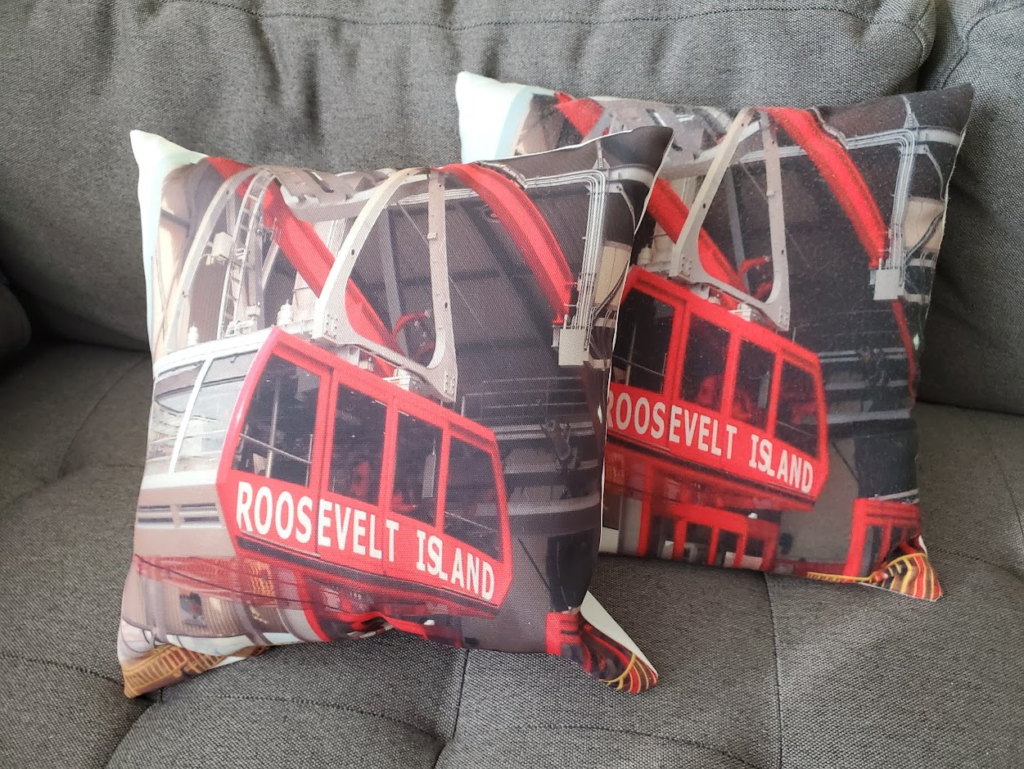

OUR JULIA GASH TAPESTRY THROWS HAVE ARRIVED.

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Oct

17

What exactly attracted William Glackens to Washington Square, leading this founding member of the Ashcan School to create more than 20 paintings set in this iconic Greenwich Village park between 1908 and 1914, according to Washington Square Park Blog?

“Washington Square Park,” 1908]

Proximity likely had something to do with it. After Glackens left his home city of Philadelphia and relocated to New York City in 1896, he found a studio on the southern edge of Washington Square, according to the New-York Historical Society. Over the years, he occupied studios at different locations on the Square.

Glackens also moved with his family into a circa-1841 townhouse at 10 West Ninth Street, steps away from Washington Arch. Here, the painter dubbed the “American Renoir” lived and worked from 1910 to his death in 1938, explains Village Preservation in a 2019 Off the Grid blog post.

[“Descending From a Bus,” 1910]

But there might be something more to it than the Square’s convenient location. At the time Glackens established himself in Greenwich Village, Washington Square “represented the demarcation between the old and new communities of New York,” according to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA).

While the descendants of many old New York families still lived in the stately brownstones of Washington Square North, “the less fashionable neighborhoods around Washington Square attracted newly arrived immigrants who worked in the factories and sweatshops nearby and also artists (including Glackens) who were drawn to the bohemian lifestyle of the district,” the MFA states

[“Italo-American Celebration,” 1912]

The presence of this new population mix in Washington Square is evident in Glackens’ 1912 painting of an Italian immigrant parade celebrating Christopher Columbus. Per the MFA: “The juxtaposition of the Old World and the New is further enhanced by the prominence of the Italian and American flags standing side by side in the lower foreground.”

What else may have influenced his decision to paint Washington Square Park, particularly his many full-color depictions of moments of leisure and pleasure?

[“29 Washington Square,” 1911]

Perhaps he was inspired by the simple loveliness of this historic square, as so many ordinary New Yorkers are as well.

OUR JULIA GASH TAPESTRY THROWS HAVE ARRIVED.

Tags: Ashcan School William Glackens in New York City, New York City in 1910s, William Glackens Impressionist NYC, William Glackens Painting Washington Square Park, William Glackens Washington Square, William Glackens Washington Square Studio

Posted in art, Lower Manhattan, Music, art, theater, West Village |

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Oct

16

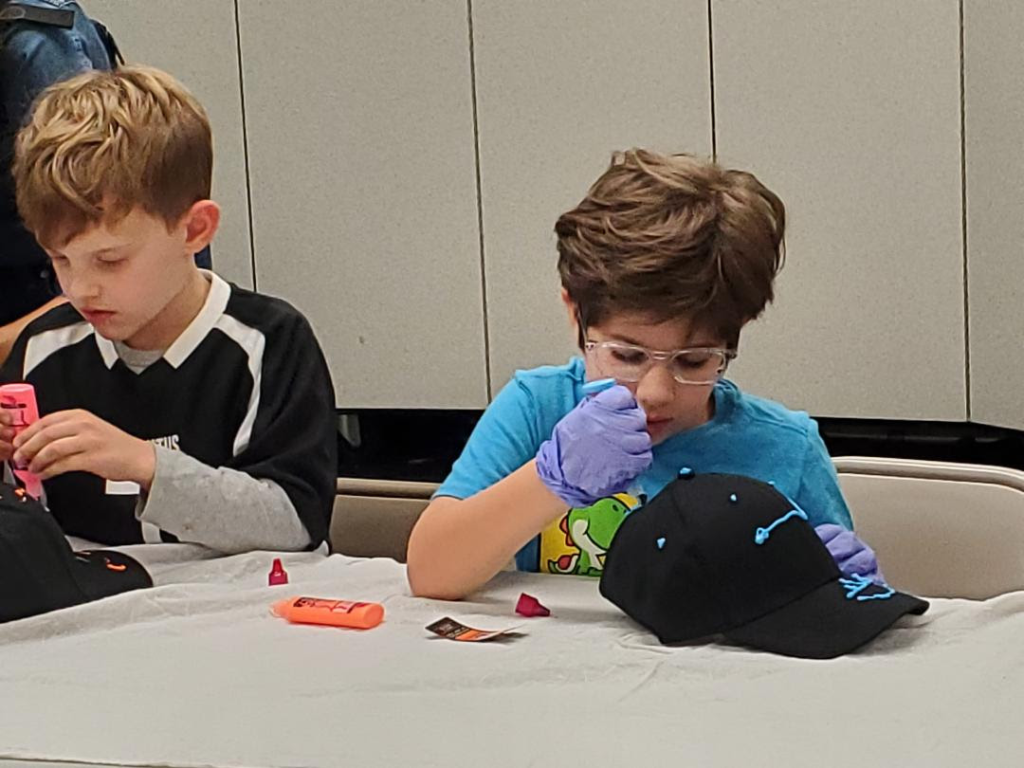

PHOTOS BY GHILA KRATZMAN AND JUDITH BERDY

George encouraged the kids (and adults) to use the paints and enjoy the fun of free flow art.

Nina and Oona with a freshly painted masterpiece

George has made cap art for years and is eager to share with others

It took two artists to work with all the kids and families

George Krassas, Chrisina Delfico and Judith Berdy enoying the activity.

The joy of free flow art!!!

It takes concentration!!!

It took me a while to find 145 Front Street in Brooklyn, Today the BQE was closed and the streets around DUMBO were jamned with impatient drivers, lots of cops and someone who has no talents with a Google map, me.

After wandering thru the hip and crowded street near York Street I finally located the small arcade where The Tagua is located. GREAT!! Wonderful displays of jewelry and creations on exhibit in this closed shop. The sign on the door said the shop would reopen October 24th.(Please change your listing on Google)

Vegetable ivory or tagua nut is a product made from the very hard white endosperm of the seeds of certain palm trees. Vegetable ivory is named for its resemblance to animal ivory. Species in the genus Phytelephas (literally “elephant plant”), native to South America, are the most important sources of vegetable ivory. The seeds of the Caroline ivory-nut palm from the Caroline Islands, natangura palm from Solomon Islands and Vanuatu,[1] and the real fan palm, from Sub-Saharan Africa, are also used to produce vegetable ivory.[2] A tagua palm can take up to 15 years to mature. But once it gets to this stage it can go on producing vegetable ivory for up to 100 years. In any given year a tagua palm can produce up to 20 pounds of vegetable ivory.[3]

The material is called corozo or corosso when used in buttons.

An early use of vegetable ivory, attested from the 1880s, was the manufacture of buttons. Rochester, New York was a center of manufacturing where the buttons were “subjected to a treatment which is secret among the Rochester manufacturers”, presumably improving their “beauty and wearing qualities”.[5] Before plastic became common in button production, about 20% of all buttons produced in the US were made of vegetable ivory.[6]

Vegetable ivory has been used extensively to make dice, knife handles, and chess pieces. It is a very hard and dense material. Similar to stone, it is too hard to carve with a knife but instead requires hacksaws and files.[1]

Vegetable ivory is naturally white with a fine marbled grain structure. It can be dyed; dyeing often brings out the grain. It is still commonly used in buttons, jewelry, and artistic carving. Many vegetable ivory buttons were decorated in a way that used the natural tagua nut colour as a contrast to the dyed surface, because the dye did not penetrate deeper than the very first layer.[1][7] This also helps identify the material.

The display of jewelry in the closed shop.

My interest was peaked by purchase of a ring.

OUR JULIA GASH TAPESTRY THROWS HAVE ARRIVED.

EACH THROW IS NEATLY PACKAGED READY TO BE GIVEN AS A GREAT HOLIDAY PRESENT

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Sep

27

September 21, 2023 by Helen Allen Nerska

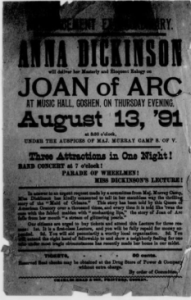

On a cold, snowy January evening in 1874, Anna Elizabeth Dickinson became one of the first women of national prominence to speak on women’s suffrage in Clinton County, NY. Those gathering to hear her at the Palmer Hall, located upstairs at 60 Margaret Street in downtown Plattsburgh, were described as the most intellectual and cultivated in the community.

The crowd that night would have known her reputation.

Dickinson was born in 1842 into a Philadelphian Quaker family. Her father was an abolitionist. She was educated at the Friends’ Select School in Philadelphia and acknowledged as a gifted speaker and prodigy.

Her first speaking engagement was in 1860 at age 18 when she addressed the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. In early 1861, when she spoke in her native city on “Women’s Rights and Wrongs,” her career on the speaking circuit began.

By 1863 Dickinson’s reputation had grown and her name appeared around the country for her anti-slavery stand during the Civil War. She was a staunch supporter of the Republican Party, though not always of Abe Lincoln, whom she felt was too moderate. Because she was a young phenom, she was elevated by some as the “Joan of Arc” of the United States’ ongoing battle to end slavery in the South.

In 1864 she was the first woman to speak before Congress and after the war she resumed her speaking career, equality for African-Americans and women’s rights. The speech was attended by Lincoln.

By 1874 she had been on the speaking circuit for nearly 15 years. During the 1871-72 lecture season she spoke almost every night from October to April commanding from $150 to $400 a night, a very large sum for its time. At her peak, she earned more than Mark Twain.

Dickinson’s spoke on “The Rights and Wrongs of Women,” Reconstruction, “Women’s Work and Wages,” and “Between Us Be Truth,” on the social evils of venereal

disease. Before arriving in Plattsburgh, she had started an acting career, climbed Pike’s Peak, and traveled the nation to give her orations on African American and women’s suffrage. (is is believed to be the first white woman to summit Colorado’s Longs Peak, Lincoln Peak, and Elbert Peak, and the second to climb Pike’s Peak.) It is unclear which organization in Plattsburgh sponsored her lecture or if admission was charged.

She entered the Palmer Hall stage not as the audience expected a radical, nonconformist to appear. Her rich brown silk dress included a train. There were diamonds on her ears, neck, and fingers. Her passport described her as 5’ 2” with large gray eyes, a fair complexion, a large Grecian nose, full lips, a round chin, and a round face. Her voice was rich, deep, and mellow, with a style betraying her Quaker training using biblical words.

Her stage presence was not that of a petite woman, and she used the entire stage to deliver her speech. She was a dramatic actress with a message. The title of her address was “What’s to Hinder Women from Helping Themselves?”

She began with the premise women are weak and dependent and need to understand how to overcome their “disabilities.” Women are their own worst enemy, she said, due to their typically gentle upbringing, women are not toughened for real work as their brothers are. Further, in order for women to do men’s work they needed to have the same training.

There would be no free ride, she argued. One will not get something for nothing. If all women are waiting for is marriage, they are not fitting themselves for good work and will not receive rewards for good work.

“The key of a woman’s success is in the brain and in the skill and cunning handle craft that come only with practice,” the Essex County Republican quoted. The reporter felt she did far more than other female orators in the country to create “a correct public sentiment for the best interests of her sex.”

After Dickinson’s 1874 lecture, Plattsburgh organizations started to host lectures by other noted suffrage supporters such as Wendell Phillips and Susan B. Anthony. But it would be 43 years before the city’s women would win the right to vote in state and federal elections.

Also a writer, Dickinson published the radical novel What Answer? (1868), supportive of interracial marriage. She made arguments for worker training, prison reform, assistance for the poor, and compulsory education for children in A Paying Investment, a Plea for Education (1876).

In the meantime, Anna was committed to against her will by her sister Susan Dickinson to the Danville State Hospital for the Insane in Pennsylvania, before being transferred to a private hospital in Goshen, Orange County, NY, where she quickly began giving lectures. She sued newspapers who claimed she was insane and those who had her committed, winning the case against her kidnapping and three libels suits in 1898.

Once released, she lived with George and Sallie Ackley in Goshen for more than 40 years. According to letters between them, and confirmed by George Ackley and his sisters, Dickinson and Sallie Ackley were lovers. When Sallie died, she left a large portion of her estate to Anna.

Anna Elizabeth Dickinson died in 1932 at the age of 89 and was buried in Slate Hill Cemetery in Goshen. A marker at her grave (next to that of the Ackleys) reads “America’s Civil War Joan of Arc,” and quotes her: “My head and heart, soul and brain, were all on fire with the words I must speak.”

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Anna Dickinson papers, including letters to Mark Twain, Susan B. Anthony, and Frederick Douglass, are located in the Library of Congress.

Illustrations, from above: A Mathew Brady photo of Anna Elizabeth Dickinson, taken between 1855 and 1865; an Anna E. Dickinson photo and autograph; and a lecture poster from 1891.

John Warren contributed to this article.

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Sep

26

In 1993, the Roosevelt Island Jewish Congregation (RIJC) moved into it’s new home in the Cultural Center. We were the only tenants along with the Main Street Theatre and Dance Alliance (MSTDA).

The RIJC held its services in the same room all year and expanded to the adjacent dance studio for high holidays and and occasional celebrations.

The MSTDA thrived under the direction of Worth and Nancy Howe, and subsequent directors.

Many other island and outside organizations used the space and it thrived as a cultural headquarters.

In the 2000’s the Cultural Center suffered two massive floods that closed the facilties for years. RIOC decided that the RIJC and MSTDA would now rent their space and other groups would also use the facilities.

The constant delays and construction issues, along with RIOC politics lead to extensive delays and postponements of usage.

Our sanctuary was no longer ours, stripped of all removable furnishings. Anyone can now rent the space for any event. We agreed to the changes and worked to reserve the space when we needed it for events.

Other groups used the space and left in frustration of dealing with RIOC. Only two groups have persevered with use of the center.

We are thirilled to be back in our “home” even for they most holy of holidays and welcome all to our Succah this Friday evening on the roof of the CUltural Center, at the 540 breezeway (on the senior center terrace) RIJC.ORG for more information.

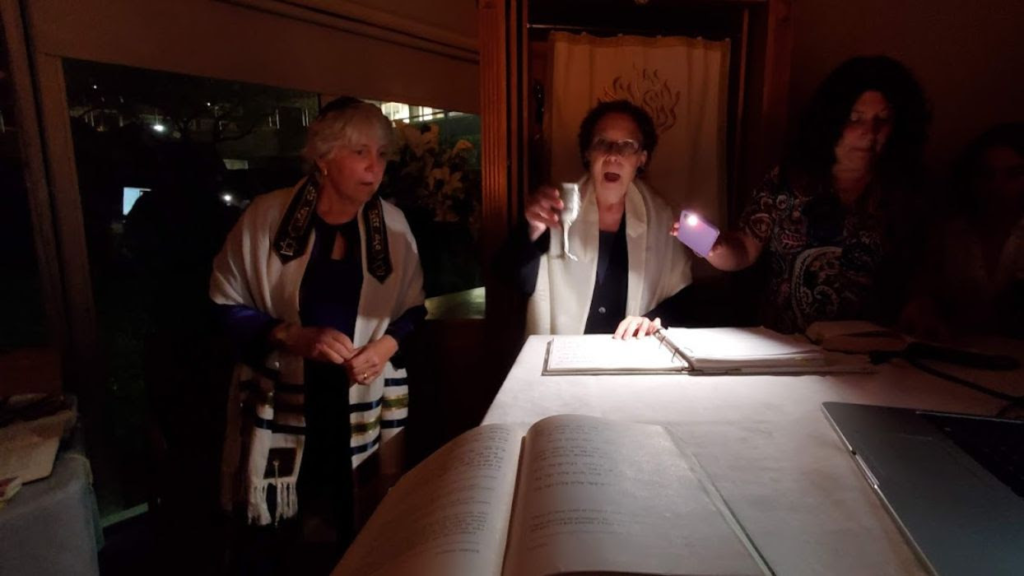

Rabbi Laurie Gold and Cantor Sandra Goodman welcoming congregants for our Yom Kippur service

The torah is read and congregants follow in person or on Zoom.

The end of the holiday is celebrated with Havdalah

NINA LUBLIN AND RABBI LAURIE GOLD AFTER THE LONG YOM KIPPUR SERVICES.

Our first decor in the sanctuary in 1990’s

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

SUZANNE VLAMIS, PHOTOGRAPH (C)

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Sep

18

VACATION TIME

I was just away on a long-needed cruise. Our trip was to start on Monday, September 4th. The ship, the Norwegian Joy was delayed due to the hurricane in Bermuda. This gave the 4,000 passengers an extra day in New York (at the cruise lines expense). I asked many of my fellow travelers how they spent the day. Here is one families story.

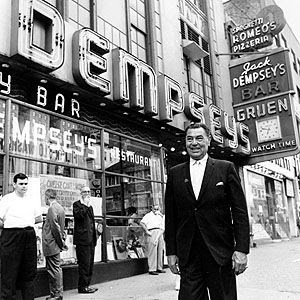

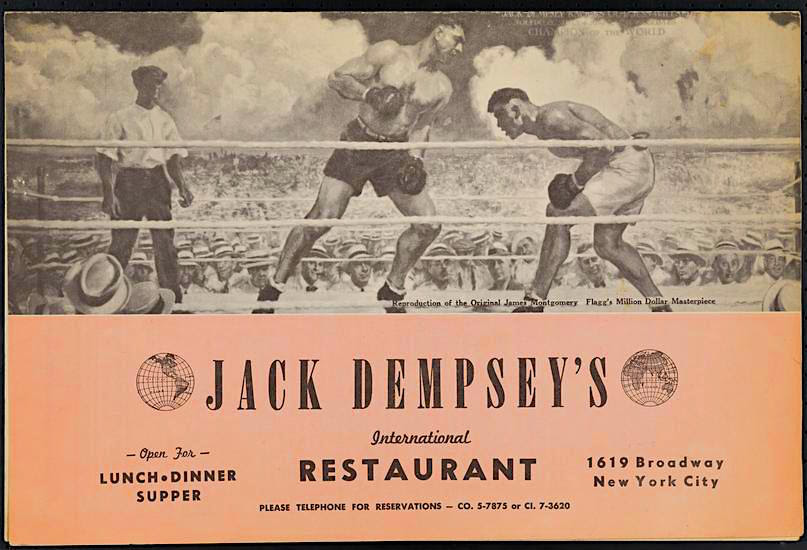

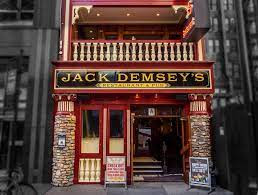

The father was in New York, in 1942, a member of the Royal Navy and waiting to sail to Europe to the battle front. As any good sailor, he found his way to Jack Dempsey’s Bar on Times Square. He sent a postcard home to England. His family kept the card and his story of having Jack Dempsey autograph it personally.

They came to our city with the mission to photograph the Jack Dempsey’s.

When told the site was the Brill Building I knew there was another story behind the address; the home of many in the music industry.

I could not wait to get home and read Daytonian in Manhattan to find our more about the Brill building.

The current Jack Demsey’s is a reproduction of the original at a new location.

Nothing, it seemed, could go wrong for Abraham E. Lefcourt prior to 1930. Born on New York’s Lower East Side, he started business manufacturing ladies’ apparel. In 1910 he built his first building, a 12-story structure at 48-54 West 25th Street that housed his factory on two floors.

In 1914 he created the Alan Realty Company–named after his 2-year old son–and continued building, erecting structures throughout the Midtown area. In 1924 Lefcourt gave his now 12-year old son ownership of a $10 million office building being erected at Madison Avenue and 34th Street. His purpose, he said, was to “inculcate in his son…a sense of thrift and responsibility.”

By 1929 Lefcourt not only commanded a vast real estate empire, but was president of the Lefcourt National Bank & Trust Company. On October 3 of that year he announced that he would build the tallest building in the world at the northwest corner of Broadway and 49th Street – the Lefcourt Building. Exceeding the Chrysler Building by four feet in height, it was to cost an estimated $30 million. Negotiations began for leasing the land from brothers Samuel, Max and Maurice Brill, where their Brill Brothers clothing store stood, and the architect Victor A. Bark, Jr. was commissioned for the project.

Nothing, it seemed, could go wrong for Abraham E. Lefcourt.

Suddenly, however, Lefcourt’s fortunes plummeted. Three weeks after his announcement, the stock market crashed. The plans for the skyscraper were quickly reworked, reducing the structure to a $1 million, 11-story office building.

Tragically, one month after the lease of the site was finalized in January 1930, 17-year old Alan Lefcourt died suddenly of anemia. Coupled with the intense grief caused by his son’s death, Lefcourt was forced to deal with a crumbling empire. In August he resigned his bank presidency to devote more time to his real estate holdings. By the end of the year he had sold no fewer the eight Manhattan buildings and investors brought suit against the bank alleging “improper investments.”

The developer continued to lose millions even as the Lefcourt-Alan Building was completed in 1931. By the fall of that year Lefcourt defaulted on the agreement with the Brill Brothers, who foreclosed. The building which he intended as a monument to his son was renamed the Brill Building.

In November 1932, with a judgment pending against him and his world collapsing, Lefcourt suddenly died. While the official report blamed a heart attack, rumors of suicide persisted. His one-time $100 million fortune was reduced to a few thousand.

| The polished brass portrait bust of young Alan Lefcourt over the main entranceCompleted in 1931, the striking Art Deco Brill Building remained, in a sense, a memorial to Alan Lefcourt. Above the entrance doors an elaborate niche holds a brass bust of the handsome youth. Another, larger bust, possibly terra cotta, graces façade at the 11th floor. Only the smaller bust is documented as being of Alan (mentioned in Abraham Lefcourt’s obituary in The New York Times as “his son’s bust over the entrance”); however the New York Landmarks Commission feels the evidence suggests the larger bust “too, represents the son, or, perhaps, an idealized male tenant.” |

The Lefcourt-Alan Building rises above Broadway on September 10, 1930 with the upper-story bust in place — photo by Edwin Levick — NYPL Collection

Perhaps more significant than the Brill Building’s striking Art Deco architecture, with its contrasting brass and polished black granite, and terra cotta reliefs, it is subsequent place in American music history.

Early tenants were music publishers, many having roots in Tin Pan Alley. Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and Tommy Dorsey had offices here along with their music publishers.

By the 1950’s radio disk jockey Alan Freed and Nat King Cole leased space here. Leiber and Stoller wrote for Elvis Presley here; Red Bird Records, famous for its “girl groups” was on the 9th Floor, and Burt Bacharach and Hal David met here in 1957 after which they wrote over 100 songs together.

Throughout the years the building was home to publishing houses such a Lewis Music, Mills Music and Leo Feist, Inc. and composers Johnny Mercer, Billy Rose, Neil Sedaka and Rose Marie McCoy. By 1962 there were 165 music businesses here.

| The larger, possibly terra cotta bust above the top floor |

Initially the entire second floor –approximately 15,000 square feet—housed The Paradise, a cabaret where music for the floorshows was supplied by bands like Glenn Miller and Paul Whiteman.

Later it became the Hurricane with tropical palms and flowers, headlining Duke Ellington. In 1944 it was Club Zanzibar where Nat King Cole, Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Jordan and the Ink Spots entertained guests in evening attire.

In the 1960’s the songs for the girl groups and teen idols that emanated from the offices here gave rise to what was called “The Brill Building Sound.” It was, according to Robert Fontenot, “poppier, more laden with strings, more giddy with romantic possibility than some of the earthier R&B stuff…This was, in other words, sophisticated pop for teens in the first blush of love, and it’s precisely that combination of classic songwriting technique and post-rock modernism that helped it get over and kept it fresh and exciting in the years since.”

Abraham Lefcourt’s striking Art Deco monument to his son was designated a New York City landmark in 2010.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

non-credited photographs were taken by the author

Posted by Tom Miller at 3:18 AM

Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Pinterest

Labels: art deco, Brill Building, james renwick jr., midtown, new york architecture, New York Landmarks, Victor A. Bark

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

May

13

IL BUCO VITA at 4 East Second Street specializes in Italian glassware, porcelain and giftware. Image a wonderful Tuscan lunch as you wander thru this small shop.

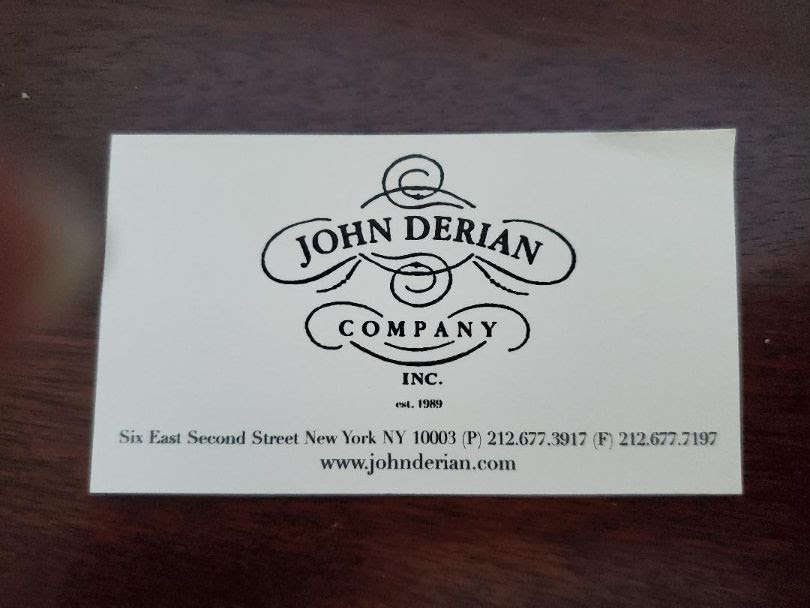

There are three John Derian shops adjoining each other. Each one is loaded with all kinds of decorative merchandise from a plate at $14- to an automated French Squirrel for $1500-.

| One shop has much housewares including bed and table linens. |

After BRIDGERTON you may need to purchase an ancestor

Trinkets from long ago safaris to countries beyond.

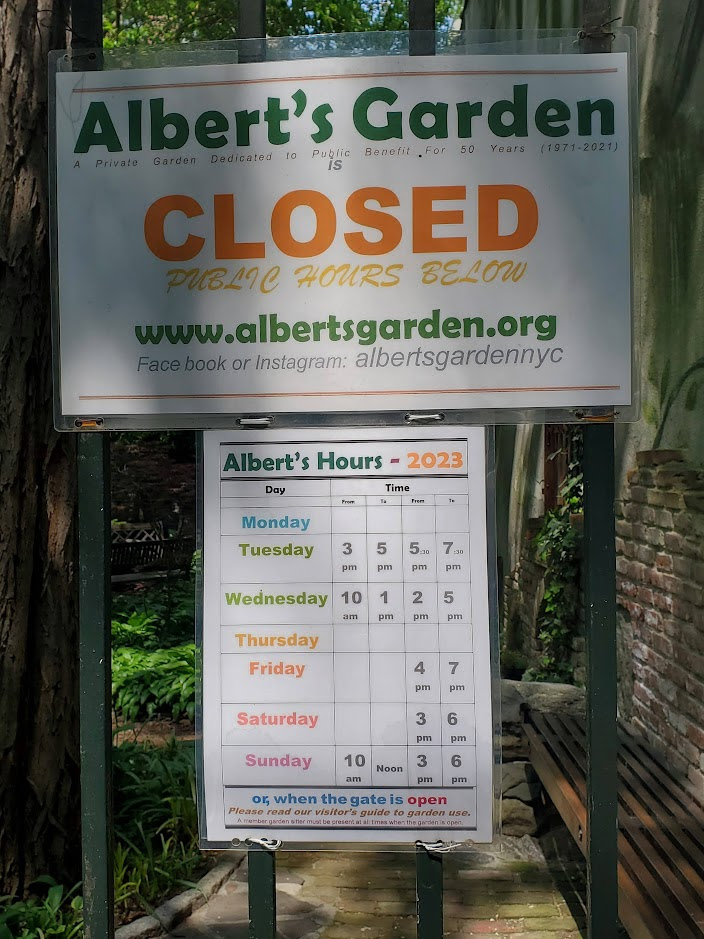

Midblock is Albert’s Garden, tucked in between buildings. A wonderful oasis.

What a wonderful spot.

The bird mural at Albert’s gate is by Belgian street artist, ROA, who is recognized for his use of wildlife imagery that is usually inspired by the local environment.

To read all about the garden go to:

https://albertsgarden.org

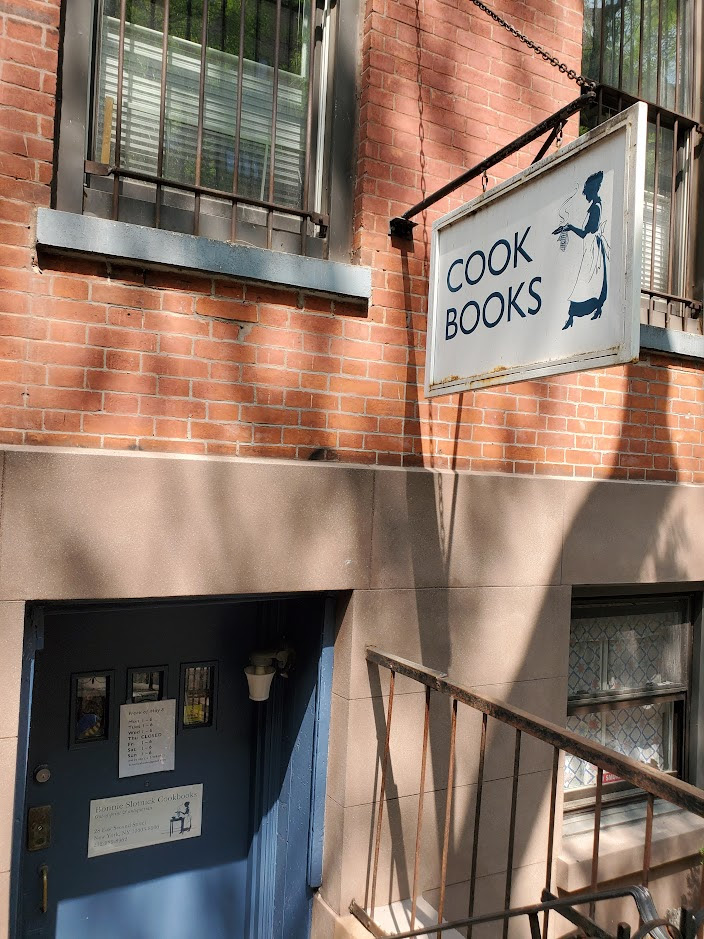

Still looking for the 1967 Harry Belafonte recording of “Matilda, try this shop.

The shop was closed but I can imagine looking for more recipes.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

May

5

Peter Senzamici,Patch Staff

Posted Wed, May 3, 2023 at 2:41 pm ET|Updated Wed, May 3, 2023 at 3:52 pm ET

Replies (3)

UPPER EAST SIDE, NY — To the untrained eye, the new East Midtown Greenway, an expansion of the East River Esplanade alongside the Upper East Side and Sutton Place, seems like it could be ready for summer fun.

But all that seems is not so.

Despite the extensive landscaping and near completion of a totally new pedestrian footbridge in Sutton Place near Clara Coffey Park at East 54th Street, the project won’t be ready for bikes, strolls and sitting until the best time of year for waterfront fun: December 2023.

As recently as a year ago, the New York City Economic Development Corporation claimed a Fall 2023 completion date.

Yvi McEvilly, an NYC EDC vice president, told Community Board 8 as recently as March 2022 that the final stage of the project, the section around Andrew Haswell Green Park, would be completed right on cue with the rest of the esplanade.

Subscribe

But according to the two most recent EDC presentations to Community Boards 6 and 8, this past October and Febuary, that while the rest of the greenway esplanade might be completed, continued work at Andrew Haswell Green Park and the Alice Aycock Pavilion will prevent them from opening the much anticipated — and needed — green space.

“We won’t be able to open just this part of the part because then it will create dead end public space, which could cause safety concerns,” said NYC EDC project director Ankita Nalavade at the February Community Board 6 meeting. “This is one of the reason why the completion of the entire project will be extend until December 2023.”

When asked for any additional details or updates about the construction, NYC EDC only told Patch that the work would be completed by the end of the year.

While neighbors find the new completion date “a little disappointing,” as one CB6 board member put it, residents are still thrilled to have another way to engage with the neighborhood’s waterfront.

Jennifer Ratner, founder of the group Friends of the East River Esplanade, called the project “a great leap forward” when it comes to creating a greenway around Manhattan.

“We are very excited about the opening of the East Midtown Greenway. We can’t wait to have even more mileage on a contiguous waterfront for runners, walkers, bikers, and people just strolling with kids and their families,” she said.

Work on the much anticipated project began in 2019, and again in September 2020 after a pandemic pause.

Even when the current construction finishes, more work will be on the way — once the project can find about $38 million.

That’s how much it’s gonna cost to enact any of the ideas Community Board 8 had for the space under Andrew Haswell Green Park, a former heliport and Sanitation waste transfer station, according to Michael Bradley, a Parks Department project administrator.

Those ideas pitched in 2018 included a bathroom or a cafe as well as a new ADA compliant ramp.

While the concrete curtain walls are mostly demolished at the structure, until the funds are secured, half of the space will be fenced off and will act as temporary Parks Department maintenance space.

The next stage of the East River Greenway — the United Nations headquarters gap — is currently in the design stage and should be ready for strolls, bikes and sits in about four years, according to NYC EDC.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Apr

3

Winners of the “Oscars of Preservation” have been announced and they feature a wide variety of historic structures across New York City. The Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award is the highest honor for excellence in preservation awarded by The New York Landmarks Conservancy. Every year the Conservancy recognizes outstanding contributions to the city from individuals, organizations, and building owners. Here, we take a look at the winners of this year’s preservation award, including a Manhattan armory, a historic lighthouse, stunning churches, and more!

In addition to the buildings being honored, Laurie Beckelman, former Chair of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, will receive the 2023 Public Leadership in Preservation Award. John J. (Jack) Kerr, Jr., attorney, will receive the Preservation Leadership Award in honor of his role in preservation’s most significant legal decisions, and for his work with many nonprofit organizations, including the Conservancy, where he served as Board Chair. Winners will be recognized at the Awards Ceremony on April 19th at 6:00 pm at Saint Bartholomew’s Church in Manhattan. You can register for tickets to attend the event here.

Church of Saint Mary the Virgin Entry Sculpture Photo Courtesy of JHPA, Inc

After two decades of being obscured by a sidewalk bridge, the restoration work at the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin can finally be seen and appreciated. The Lucy G. Moses Award-winning project has revealed a newly restored limestone and brick façade. Restored limestone statues by John Massey Rhind are out in the open once again on 46th Street.

Known as Smoky Mary’s, for the generous incense used in services, the church was designed by Napoleon LeBrun and Sons in the French Gothic Revival style. Completed in 1895, it was the first building in the world to use steel frame construction, eliminating the need for flying buttress supports and permitting a large interior on a narrow lot.

Photo (c) Albert Vecerka Esto

Restoration work on 131 Duane Street in the Tribeca South Historic District revealed the building’s historic “Hope Building” sign. A team of preservation professionals rediscovered the sign while restoring the structure’s original marble, brick, and cast iron façade, paying careful attention to the ornate architectural details.

Now a mixed-use building with lofts, retail and amenity spaces, and a two-story rooftop penthouse, the building was originally constructed in 1863 by Thomas Hope. It housed a variety of dry goods companies and shoe manufacturers. The upper floors were converted for residential use in the 1970s.

Photo by Michael Middleton/ Li Saltzman Architects

The Church of St. Luke and St. Matthew is made up of seven different stone types to achieve its unique polychrome design. Completed in 1891, the church exemplifies the Italian Romanesque Revival style.

This restoration project which will receive the Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award has stabilized and restored the monumental façade and stained glass, and repaired a hole in the roof. The project was funded in tandem with zoning changes to a nearby new development.

Photo by Mary Kay Judy

1065 Clay Avenue in the Bronx was once a vacant wreck. Now, the formerly abandoned residence has been transformed into a home by the current owners Ali and Farah Mozaffari. Located within the Clay Avenue Historic District, the Mozaffari’s home has become a beacon of renewal.

The three-story house, which is attached to a twin, boasts a Roman brick facade with prominent three-sided angled bays. There are Flemish-inspired gables at the roofline above the wrought-iron railings encircled balcony created by the bays. It is clear that much work and care has gone into the restoration of this historic home to bring it back to its former brilliance.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com