MONDAY, MAY 4, 2020 ELLIS ISLAND IMMIGRATION STATION

MONDAY

MAY 4, 2020

RIHS’s 42nd Issue of

Included in this Issue:

Ellis Island Immigration Station

REMEMBRANCES

My Visits to Ellis Island

1995 & 2006

CELEBRATING ISLANDS WEEK

NORTH BROTHER

WARD’S & RANDALL’S

BEDLOE’S

HOFFMAN & SWINBURNE

GOVERNORS

CONEY ISLAND

AND NOW

ELLIS ISLAND

The New Colossus

Emma Lazarus – 1849-1887 •

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch,

whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning,

and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows world-wide welcome;

her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips.

“Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless

tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

From Military Fort to National Gateway

From 1794 to 1890 (pre-immigration station period), Ellis Island played a mostly uneventful but still important military role in United States history. When the British occupied New York City during the duration of the Revolutionary War, its large and powerful naval fleet was able to sail unimpeded directly into New York Harbor.

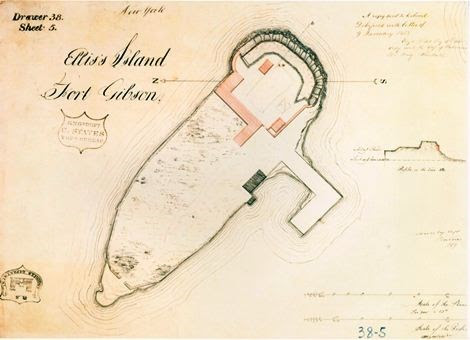

Therefore, it was deemed critical by the United States Government that a series of coastal fortifications in New York Harbor be constructed just prior to the War of 1812. After much legal haggling over ownership of the island, the Federal government purchased Ellis Island from New York State in 1808.

Ellis Island was approved as a site for fortifications and on it was constructed a parapet for three tiers of circular guns, making the island part of the new harbor defense system that included Castle Clinton at the Battery, Castle Williams on Governor’s Island, Fort Wood on Bedloe’s Island and two earthworks forts at the entrance to New York Harbor at the Verrazano Narrows.

The fort at Ellis Island was named Fort Gibson in honor of a brave officer killed during the War of 1812.

Immigration Policy Embraces the Masses

Prior to 1890, the individual states (rather than the Federal government) regulated immigration into the United States. Castle Garden in the Battery (originally known as Castle Clinton) served as the New York State immigration station from 1855 to 1890 and approximately eight million immigrants, mostly from Northern and Western Europe, passed through its doors.

These early immigrants came from nations such as England, Ireland, Germany and the Scandinavian countries and constituted the first large wave of immigrants that settled and populated the United States. Throughout the 1800s and intensifying in the latter half of the 19th century, ensuing political instability, restrictive religious laws and deteriorating economic conditions in Europe began to fuel the largest mass human migration in the history of the world. It soon became apparent that Castle Garden was ill-equipped and unprepared to handle the growing numbers of immigrants arriving yearly.

Unfortunately, compounding the problems of the small facility were the corruption and incompetence found to be commonplace at Castle Garden. The Federal government intervened and constructed a new Federally-operated immigration station on Ellis Island.

While the new immigration station on Ellis Island was under construction, the Barge Office at the Battery was used for the processing of immigrants. The new structure on Ellis Island, built of “Georgia pine” opened on January 1, 1892.

Annie Moore, a teenaged Irish girl, accompanied by her two brothers, entered history and a new country as she was the very first immigrant to be processed at Ellis Island. Over the next 62 years, more than 12 million were to follow through this port of entry.

Ellis Island Burns and Years of Records Lost

While there were many reasons to immigrate to America, no reason could be found for what would occur only five years after the Ellis Island Immigration Station opened. During the early morning hours of June 15, 1897, a fire on Ellis Island burned the immigration station completely to the ground.

Although no lives were lost, many years of Federal and State immigration records dating back to 1855 burned along with the pine buildings that failed to protect them.

The United States Treasury quickly ordered the immigration facility be replaced under one very important condition: all future structures built on Ellis Island had to be fireproof. On December 17, 1900, the new Main Building was opened and 2,251 immigrants were received that day.

Journeying By Ship to the Land of Liberty

While most immigrants entered the United States through New York Harbor (the most popular destination of steamship companies), others sailed into many ports such as Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco, Savannah, Miami, and New Orleans.

The great steamship companies like White Star, Red Star, Cunard and Hamburg-America played a significant role in the history of Ellis Island and immigration in general. First and second class passengers who arrived in New York Harbor were not required to undergo the inspection process at Ellis Island. Instead, these passengers underwent a cursory inspection aboard ship, the theory being that if a person could afford to purchase a first or second class ticket, they were less likely to become a public charge in America due to medical or legal reasons.

The Federal government felt that these more affluent passengers would not end up in institutions, hospitals or become a burden to the state. However, first and second class passengers were sent to Ellis Island for further inspection if they were sick or had legal problems.

This scenario was far different for “steerage” or third class passengers. These immigrants traveled in crowded and often unsanitary conditions near the bottom of steamships with few amenities, often spending up to two weeks seasick in their bunks during rough Atlantic Ocean crossings. Upon arrival in New York City, ships would dock at the Hudson or East River piers. First and second class passengers would disembark, pass through Customs at the piers and were free to enter the United States. The steerage and third class passengers were transported from the pier by ferry or barge to Ellis Island where everyone would undergo a medical and legal inspection.

Arrival at the Island and Initial Inspection

If the immigrant’s papers were in order and they were in reasonably good health, the Ellis Island inspection process would last approximately three to five hours. The inspections took place in the Registry Room (or Great Hall), where doctors would briefly scan every immigrant for obvious physical ailments. Doctors at Ellis Island soon became very adept at conducting these “six second physicals.”

By 1916, it was said that a doctor could identify numerous medical conditions (ranging from anemia to goiters to varicose veins) just by glancing at an immigrant. The ship’s manifest log, that had been filled out back at the port of embarkation, contained the immigrant’s name and his/her answers to twenty-nine questions. This document was used by the legal inspectors at Ellis Island to cross-examine the immigrant during the legal (or primary) inspection.

The two agencies responsible for processing immigrants at Ellis Island were the United States Public Health Service and the Bureau of Immigration (later known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service – INS). Despite the island’s reputation as an “Island of Tears”, the vast majority of immigrants were treated courteously and respectfully, and were free to begin their new lives in America after only a few short hours on Ellis Island.

Only two percent of the arriving immigrants were excluded from entry. The two main reasons why an immigrant would be excluded were if a doctor diagnosed that the immigrant had a contagious disease that would endanger the public health or if a legal inspector thought the immigrant was likely to become a public charge or an illegal contract laborer.

Immigration Laws and Regulations Evolve

From the very beginning of the mass migration that spanned the years 1880 to 1924, an increasingly vociferous group of politicians and nativists demanded increased restrictions on immigration. Laws and regulations such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Alien Contract Labor Law and the institution of a literacy test barely stemmed this flood tide of new immigrants. Actually, the death knell for Ellis Island, as a major entry point for new immigrants, began to toll in 1921. It reached a crescendo between 1921 with the passage of the Quota Laws and 1924 with the passage of the National Origins Act.

These restrictions were based upon a percentage system according to the number of ethnic groups already living in the United States as per the 1890 and 1910 Census. It was an attempt to preserve the ethnic flavor of the “old immigrants”, those earlier settlers primarily from Northern and Western Europe. The perception existed that the newly arriving immigrants mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe were somehow inferior to those who arrived earlier.

After World War I, the United States began to emerge as a potential world power. United States embassies were established in countries all over the world, and prospective immigrants now applied for their visas at American consulates in their countries of origin. The necessary paperwork was completed at the consulate and a medical inspection was also conducted there. After 1924, the only people who were detained at Ellis Island were those who had problems with their paperwork, as well as war refugees and displaced persons. Ellis Island still remained open for many years and served a multitude of purposes.

During World War II, enemy merchant seamen were detained in the baggage and dormitory building. The United States Coast Guard also trained about 60,000 servicemen there. In November of 1954, the last detainee, a Norwegian merchant seaman named Arne Peterssen, was released, and Ellis Island officially closed.

REMEMBRANCES

Judith Berdy

1995 & 2006

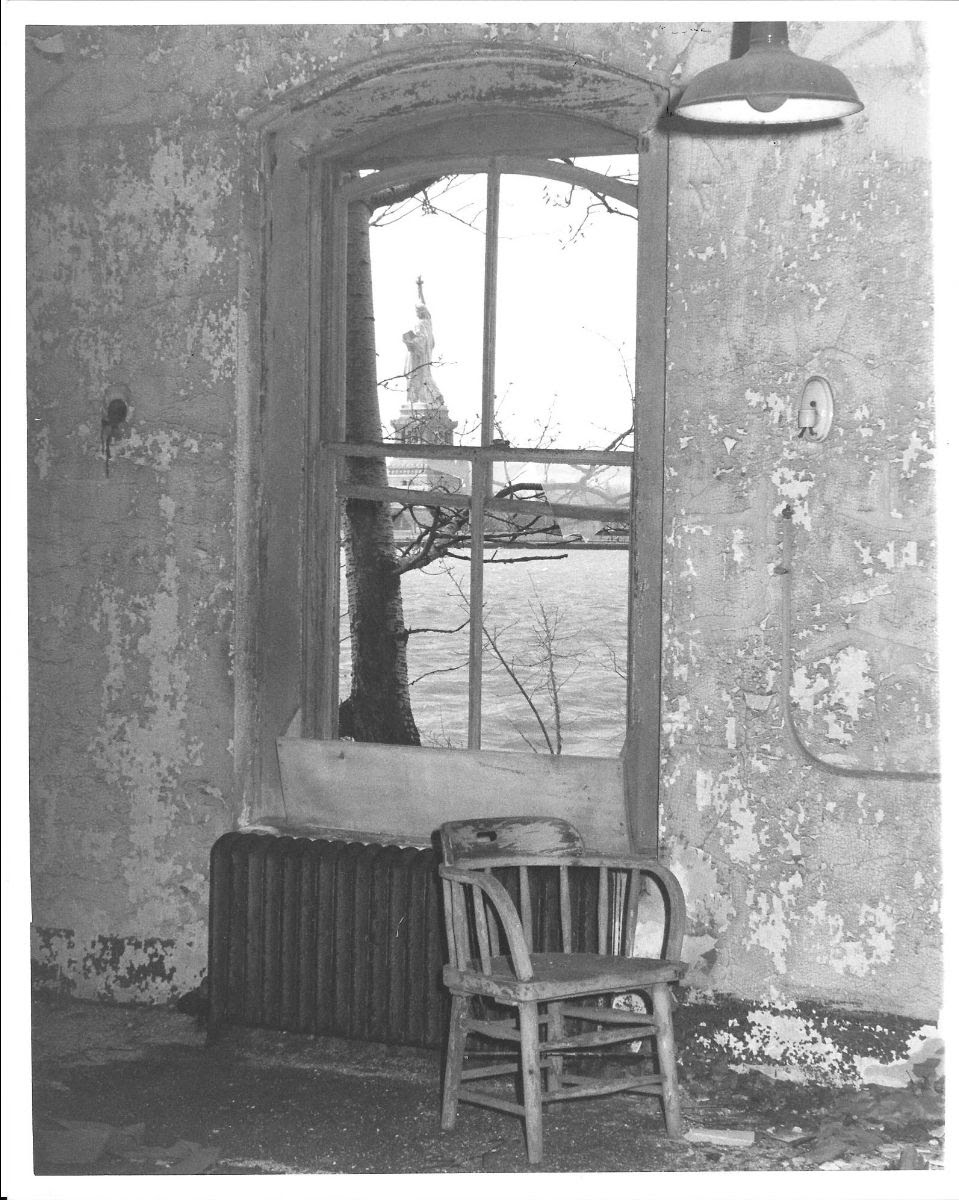

In 1995 I was contacted by a staff member at Ellis Island. In exchange for information on Roosevelt Island he offered a friend and myself tour of the “other” south side of the island. In 1995, the hospital part of the island was not open to the public and was in hazardous condition, wanting me more to see it.

I remember it was a freezing cold day and we walked thru the enormous kitchen in the main building.

Text by Judith Berdy

Photos (c) RIHS

There was a row of kettles for soups and in the corner a Hobart mixer (making bread dough). The kitchen was vast and in abandoned state.

We walked in a long corridor with windows on each side, past the ferry landing and onto the other part of the island. Th weeds and broken glass with wind blowing was an interesting experience.

and fenced in entries.

EDITORIAL

The hospital at Ellis has a fascinating history, which we did not have space for in this issue. The glass enclosed corridors we walked thru lead to the hospital where persons were treated and most released to become Americans.

Thanks to the STATUE OF LIBERTY ELLIS ISLAND FOUNDATION (c) for the historical information.

There are hat tours of the abandoned buildings and reservations are available online.

Ellis, like Blackwell’s had a community of staff that lived and worked on the island. Their story soon.

Best wishes,

Judith Berdy

212 688 4836

jbird134@aol.com

From Bonnie Waldman about our weekend Coney Island issue:

I have so many great memories of Steeplechase Park. I went there a couple of times each summer from the late 1940’s and all through the 50’s. I rode the Electric Horses with my older brother and rode the parachute with him as well as the Wonder Wheel. I would scream so loud when the car suddenly swung back and forth. One time I “burned” my back going down the giant curved wooden slide. it was REALLY high. I was wearing a midriff so much of my back was exposed to the wood and because I was leaning back instead of sitting up I came off the ride in pain. My mother brought me to the Infirmary that was hidden away off to the side of all the amusements. The nurse put a thick salve on the affected areas. But what I remember most was a midget man clown resting on one of the tables and me wondering what was hurting him. Judy, thanks for jogging my memories of my old Brooklyn.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment