December 5/6, 2020 – His work was more than one asylum

WEEKEND EDITION

DECEMBER 5-6, 2020

228th Edition

ALEXANDER JACKSON DAVIS,

ARCHITECT

Stephen Blank

RIHS

Dec. 3, 2020

Another famous architect on Roosevelt Island! Alexander Jackson Davis (1803–1892) is widely considered America’s greatest architect of the mid-nineteenth century. “Imaginative, innovative and influential, Alexander J. Davis was an extraordinary figure in American architecture…He introduced and developed new ideas and new forms while producing some of the finest buildings of his time,” writes Jane Davis in the introduction to the splendid volume, Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect 1803-1892.

Davis’ work covers a broad range of fields – public buildings, universities, grand mansions, interiors and, perhaps his greatest love, gardens. And, back to our island, he and his partner, Ithiel Town, designed our Lunatic Asylum – our Octagon.

Born in New York City on July 24, 1803, the son of a bookseller and publisher of religious tracts who moved around the Northeast in search of a market for his works, Davis grew up in Newark and then the rapidly growing towns of Utica and Auburn in central New York State.

In these years, the US was booming. The purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803 doubled the size of the new nation, and from 1800 to 1860, 17 new states joined the Union. In these years, millions of immigrants came from other countries. US population more than tripled from 1800 to 1850, from 7 million to 24 million. Our fiscal system remained chaotic and bank failures were not uncommon (in 1837, the country suffered a huge fiscal crisis). Issues of the future of slavery roiled politics, but there was a lot of money about and a new class of wealthy drove the emergence of a new American cultural life

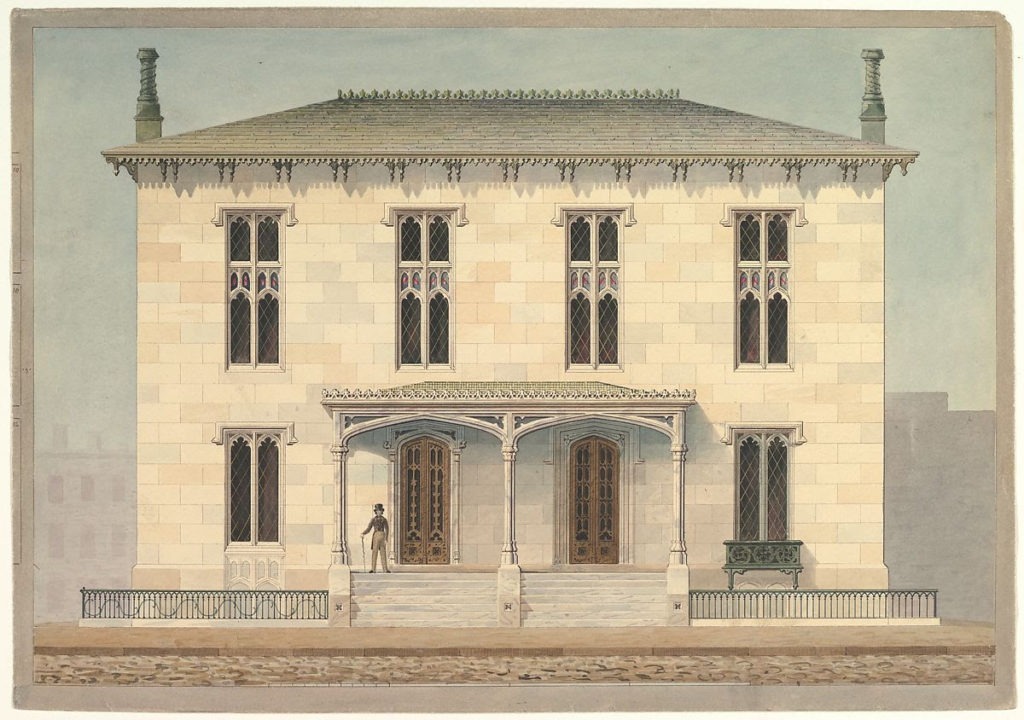

Grace Hill for Edwin C. Litchfield, Brooklyn, New York (front elevation)1854

Alexander Jackson Davis American

Davis’ greatest Italianate villa, Grace Hill, is now the headquarters of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. The original stucco has been removed from the house, and many of the interior details, including the elaborately painted ceiling murals, have been lost. Davis also designed a coach house, greenhouse, and chicken house for the property, none of which are extant.

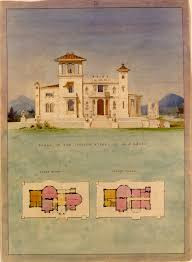

Proposal for Astor House (Park Hotel), New York (perspective)ca. 1830–34

Designed by Ithiel Town American

This drawing shows a design produced by A.J. Davis and Ithiel Town (as Town & Davis, 1829-1835) for the Astor House, the first luxury hotel in New York City envisioned by John Jacob Astor. Although Town & Davis’ imaginative study was very modern and quite spectacular, the actual commission went to Isaiah Rogers in 1834 and the hotel opened in 1836 as the Park Hotel. The south side of the building was demolished in 1913 to make way for the subway constructions, and the rest of the building was torn down in 1926.

Davis at 14 was sent to Alexandria, Virginia, to learn the printing trade in a half-brother’s newspaper office. When his apprenticeship was completed in 1823, he returned to New York City where he studied at the American Academy of the Fine Arts and other top art schools.

New York City was growing rapidly, with an 1820 population of 122,000, but it was still a pretty small community for artists. Young Davis knew many, including John Trumbull, Samuel F. B. Morse, and Rembrandt Peale. His friends advised him to concentrate on architectural drawing – and he went to work as a draftsman in 1826 for Josiah R. Brady, a New York architect who was an early exponent of the Gothic revival.

He was successful as an architectural illustrator and his drawings were widely published, but he soon moved on from drawing buildings (though his drafting skills remained central to his identity) to designing them. Davis set up a practice and his first executed design was a country house outside of New Haven, Connecticut for the poet James A. Hillhouse. His Greek Revival design piqued the interest of Ithiel Town, one of the premier architects of the time and the leading designer of Greek Revival style buildings. Davis joined the firm of Town and Martin E. Thompson and, in 1829, became a partner. Working with Town gave Davis, just 26, extraordinary opportunities. It brought him to the cutting edge of American architecture—Town was not only a leader in the Greek Revival style, he was also a respected engineer and enjoyed wide social contacts.

ABOVE: INDIANA CAPITOL

BELOW: lLYNDHURST

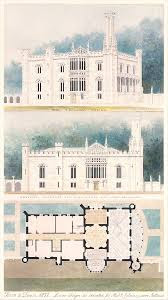

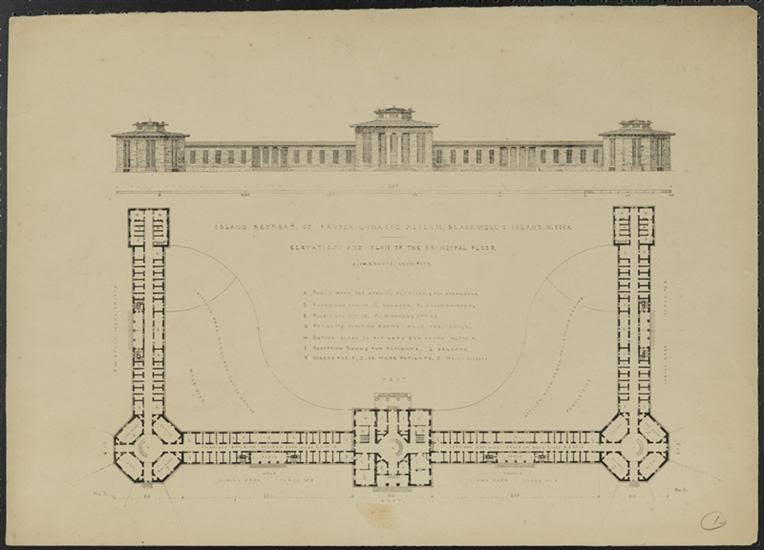

ASYLUM PLAN AND RENDERING

In the six years he spent with Town, in what became the first recognizably modern architectural office, Davis developed into a brilliantly original designer. He designed many late Classical structures, including several well-known buildings in Washington DC. We recognize him because he and Pool were the architects of the Custom House of New York City (now known as Federal Hall, where in an earlier iteration George Washington was sworn in as our first president). Federal Hall is one of the best surviving examples of Greek Revival architecture in New York, and was the first purpose-built U.S. Custom House for the Port of New York.

After the Town-Davis firm submitted the winning design for the State of Indiana capitol building (modeled on the Parthenon except for a large central dome) and then completed it ahead of schedule, the firm was consulted on the design of several other state capitols –- North Carolina, Illinois and Ohio. Back in New York City, they designed the Greek Revival “Colonnade Row” on Lafayette Street, the first apartments designed for the prosperous American middle class, and built several iimportant New York churches and several impressive residences: Samuel Ward’s New York City house (1831-33) included an art gallery, pilasters and introduced columns in the townhouse doorways. “Glen Ellen,” a large country estate built for Robert Gilmor outside of Baltimore, Maryland, was an early indicator of Davis’ future career. Davis designed buildings for the University of Michigan in 1838, and in the 1840s he designed buildings for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. At Virginia Military Institute, Davis’s designs from 1848 through the 1850s created the first entirely Gothic revival college campus.

Davis and Town also designed the Blackwell Island Lunatic asylum, though only some of which was ever built. More on this will come.

The partnership with Town was dissolved in 1835, and Davis worked without an architectural partner for the remainder of his career. In 1836, he began writing Rural Residences, the first American book about the design of country houses, illustrated with hand-colored lithographs that helped introduce the concepts of picturesque architecture to the United States. His many drawings and watercolors provide idealized documents of mid-nineteenth-century designed landscapes as they were built and imagined.

Because of the 1837 financial panic, only two of the proposed six parts of the book were issued. But in 1839, he joined with the influential landscape and architectural theorist A. J. Downing in a most important collaboration. Davis designed and drew illustrations for Downing’s widely read books, such as The Architecture of Country Houses (1850) and his journal, The Horticulturist. Together, they popularized the ideas and styles of the picturesque.

Yes, the same Downing who invited Frederick Chase Withers to come to the United States and became his partner (and brother-in-law), a partnership which included Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmstead. Talk about small worlds!

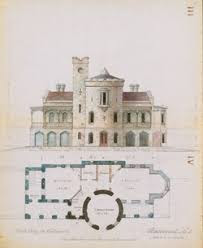

In the 1840s and ‘50s, Davis shone brightly as a designer for country houses. Over 100 of his designs for villas and cottages were built among which “Lyndhurst” at Tarrytown is the most famous. Davis developed two main types of residential structures: large, asymmetrical villas for wealthy clients and smaller rectangular cottages intended for clients of more modest means. Both types featured a veranda or porch wrapped around the building, which connected the house to its immediate surroundings, while his villas often incorporated “prospect towers” or “prospect rooms” that provided sweeping views of the landscapeFor some houses he drew interior details, and occasionally designed furniture. Many of his villas were built in the Hudson River Valley— and his style called Hudson River Bracketed gave Edith Wharton a title for her last novel — but Davis also sent plans and specifications to clients far away from New York. He was crucial in transforming the English idea of picturesque into an American Romanticism. Davis felt the English house style was too grand for the new republican nation, and insisted on the individualism of Americans by varying each house design to it landscape as well as owner’s tastes. His designs were instrumental in opening up the boxy American house form, and moved toward open floor plans. (Are we thinking Frank Lloyd Wright?) All of this was carried out as the Hudson River setting was being popularized and romanticized by the Hudson River School of artists – again the close connections in style and setting among these new America-focused artists and designers.

With the onset of Civil War in 1861, patronage in house building dried up, and after the war, new popular styles were unsympathetic to Davis’s work. He closed his office in 1878 and built little in the last thirty years of his life. Rather he spent his easy retirement in West Orange drawing plans for grandiose schemes that he never expected to build, and selecting and ordering his designs and papers

So what about the Lunatic Asylum?

This section is taken largely from the fine materials prepared by the RIHS (think Jude Berdy.) The Blackwell’s island Asylum was the first lunatic asylum for the city of New York and the first municipal mental hospital in the country as well as the first in what later became a larger system of New York City Asylums comprised of hospitals on Blackwell’s, Ward’s, and more briefly Hart’s and Randall’s Islands. Up to 1825, the city’s insane were either kept in the city almshouse or at the Bloomingdale Asylum. In 1825 the insane of the city were moved to the basement and first floor of a building built as a General Hospital on Blackwell’s Island. Here the mentally ill remained in conditions described by the very commissioners in charge of the hospital as “a miserable refuge for their trial, undeserving of the name Asylum, in these enlightened days”.

Only in 1834 did the city approve the construction of a separate institution for the insane on the island. Designs for the Asylum were prepared by Davis and Town in 1834-35, and the building was opened in 1839. Their plans called for a much more elaborate scheme than was actually built; the Octagon was to have been one of a pair within a great U-shaped complex, ordered around a central rectangular pavilion. As built, the single Octagon, from which two long wings extended, became the focal point of the building.

The architectural historian, Talbot Hamlin, has praised Davis’ “consistent feeling for logical planning.” The original symmetrical plan for the Asylum took into account efficient supervision of patients, ease of circulation and ample provision for good lighting and ventilation in the wards. Davis’ plan was a variant of the influential “panoptic plan,” which was centralized with radiating wings, developed in Great Britain by Jeremy Bentham (1742-1832), a philosopher and jurist interested in prison reform. While only a portion of Davis’ original proposal for the Lunatic Asylum was actually built, the plan still functioned very effectively. Davis’ New York City Asylum project was also significant in that it served as the prototype for his North Carolina Hospital for the Insane at Raleigh.

Dr. R.L. Parsons, Resident Physician of the Lunatic Asylum during the 1860s, remarked in his annual report of 1865 that the Octagon “has a symmetry, a beauty and a grandeur even, that are to be admired.” These qualities are still in evidence, not only to the visitor to Roosevelt Island, but also from Manhattan where the picturesque silhouette of the Octagon is a prominent feature of the island’s skyline.

WEEKEND PHOTO

SEND IN YOUR SUBMISSION

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WIN A TRINKET FROM THE KIOSK SHOP

FRIDAY PHOTOS OF THE DAY

Did you guess them?Trestle Bridge, Roosevelt Island Bridge

London Tower Bridge, Pont Neuf, Paris

Bow Bridge, Central Park., Hellgate Bridge, New York

References

Wikipedia

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/davs/hd_davs.htm

https://tclf.org/pioneer/alexander-jackson-davis

https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/Alexander_Jackson_Davis

http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/nyhs/davis/bioghist.html

https://rihs.us/landmarks/octagon.htm

Amelia Peck, ed., Alexander Jackson Davis, American Architect 1803-1892

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.

Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment