Monday, February 15, 2021 – A Barthe artwork brings attention to the wonderful sculptor

TOMORROW

USE THIS LINK TO REGISTER FOR PROGRAM.

A LIBRARY CARD NUMBER IS NOT REQUIRED

AN E-MAIL

CONFIRMATION WILL BE SENT

https://www.nypl.org/events/programs/2021/02/16/nyta-objects

287th Edition

Monday,

February 15, 2021

James Richmond Barthé,

Richmond Barthé (January 28, 1901 – March 5, 1989) was an African-American sculptor associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Barthé is best known for his portrayal of black subjects. The focus of his artistic work was portraying the diversity and spirituality of man. Barthé once said: “All my life I have been interested in trying to capture the spiritual quality I see and feel in people, and I feel that the human figure as God made it, is the best means of expressing this spirit in man.”

FROM WIKIPEDIA

RICHMOND BARTHE

HARLEM RENAISSANCE-ERA FRIEZE AT KINGSBOROUGH HOUSES TO BE RESTORED

“Exodus and Dance” by Richmond Barthé depicts African-American figures engaged in collective dance. Photo by Michele H. Bogart

from Brooklyn Paper by Jessica Parks

A crumbling Harlem Renaissance-era sculpture at Crown Heights’ Kingsborough Houses is getting a much-needed facelift following decades of neglect. “The artwork is falling apart,” said Larry Weeks, Fulton Art Fair treasurer and neighbor of the Kingsborough Houses. “I would walk through there and I would see it and say this piece needs some tender loving care.”

Richmond Barthé — a gay, Black sculpturist prominent in the city’s art revival era — built the frieze, titled “Exodus and Dance,” on commission for an amphitheater that was never built at the Harlem River Houses, a mostly-Black housing complex at the time. Instead, the artwork traveled across the East River to the Kingsborough Houses, which had a mostly-white population, in 1941.

The sculpted-stone mural can now be seen at the New York City Housing Authority complex, although it exists in a state of disrepair — suffering from cracks due to rainwater and a bad patchwork job, according to one of the project’s advocates. “The work of cast stone was literally cracked and crumbling and you could put a finger through sections of it,” said Michelle Bogart, an author and art history professor.

“The immediate approaches to it are crumbling too… there was patching that had been done but very badly.” The restoration is a result of the combined effort of a number of people and organizations — which is said to have begun in 2018, when Bogart drew attention to the artwork’s dilapidated state on Twitter, and when the Weeksville Heritage Center and Fulton Art Fair began reaching out to their councilmember.

“So I was just simply trying to draw awareness to the work, so I started tagging [First Lady] Chirlane McCray and [Councilmember] Alicka Ampry-Samuels,” Bogart said. “And it was on that basis that some people saw it.” Their pleas eventually reached the right people, and moves were made to preserve Barthé’s largest work of art — in a project costing a whopping $1.8 million. “NYCHA continues to move forward with the in-house work on the Barthé frieze,” said a NYCHA spokeswoman. “In 2018, the Public Design Commission, NYCHA, and Speaker Corey Johnson’s staff met to discuss the conservation of this work, and The Speaker allocated $1.8 million for the work to be done.

BARTHE’S LIFE AND OTHER WORKS

Early life

James Richmond Barthé was born in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. His father’s name is Richmond Barthé and mother’s name is Marie Clementine Robateau. Barthé’s father died at age 22, when he was only a few months old, leaving his mother to raise him alone. She worked as a dressmaker and before Barthé began elementary school she remarried to William Franklin, with whom she eventually had five additional children.

Barthé showed a passion and skill for drawing from an early age. His mother was, in many ways, instrumental in his decision to pursue art as a vocation. Barthé once said: “When I was crawling on the floor, my mother gave me paper and pencil to play with. It kept me quiet while she did her errands. At six years old I started painting. A lady my mother sewed for gave me a set of watercolors. By that time, I could draw very well.”

Barthé continued making drawings throughout his childhood and adolescence, under the encouragement of his teachers. His fourth grade teacher, Inez Labat, from the Bay St. Louis Public School, influenced his aesthetic development by encouraging his artistic growth. When he was only twelve years old, Barthé exhibited his work at the Bay St. Louis Country Fair.

However, young Barthé was beset with health problems, and after an attack of typhoid fever at age 14, he withdrew from school.[6] Following this, he worked as a houseboy and handyman, but still spent his free time drawing. A wealthy family, the Ponds, who spent summers at Bay St. Louis, invited Barthé to work for them as a houseboy in New Orleans, Louisiana. Through his employment with the Ponds, Barthé broadened his cultural horizons and knowledge of art, and was introduced to Lyle Saxon, a local writer for the Times Picayune. Saxon was fighting against the racist system of school segregation, and tried unsuccessfully to get Barthé registered in an art school in New Orleans.

In 1924, Barthé donated his first oil painting to a local Catholic church to be auctioned at a fundraiser. Impressed by his talent, Reverend Harry F. Kane encouraged Barthé to pursue his artistic career and raised money for him to undertake studies in fine art. At age 23, with less than a high school education and no formal training in art, Barthé applied to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago, and was accepted by the latter.

Josephine Baker 1951

Chicago

During the next four years Barthé followed a curriculum structured for majors in painting. During this time he boarded with his aunt Rose and made a living working different jobs.[9] His work caught the attention of Dr. Charles Maceo Thompson, a patron of the arts and supporter of many talented young black artists. Barthé was a flattering portrait painter, and Dr. Thompson helped him to secure many lucrative commissions from the city’s affluent black citizens.

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Barthé’s formal artistic instruction in sculpture took place in anatomy class with professor of anatomy and German artist Charles Schroeder. Students practiced modeling in clay to gain a better understanding of the three-dimensional form. This experience proved to be, according to Barthé, a turning point in his career, shifting his attention away from painting and toward sculpture.[

Barthé had his debut as a professional sculptor at The Negro in Art Week exhibition in 1927 while still a student of painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. He also exhibited in the April 1928 annual exhibition of the Chicago Art League. The critical acclaim allowed Barthé to enjoy numerous important commissions such as the busts of Henry O. Tanner (1928) and Toussaint L’Ouverture (1928). Although he was still in his late 20s, within a short time he won recognition, primarily through his sculptures, for making significant contributions to modern African American art. By 1929, the essentials of his artistic education complete, Barthé decided to leave Chicago and head for New York City.

New York City

While many young artists found it very difficult to earn a living from their art during the Great Depression, the 1930s were Richmond Barthé’s most prolific years. The shift from the Art Institute of Chicago to New York City, where he moved following graduation, exposed Barthé to new experiences as he arrived in the city during the peak of the Harlem Renaissance. He established his studio in Harlem in 1930 after winning the Julius Rosenwald Fund fellowship at his first solo exhibition at the Women’s City Club in Chicago. However, in 1931, he moved his studio in Harlem to Greenwich Village. Barthé once said: “I live downtown because it is much more convenient for my contacts from whom it is possible for me to make a living.” He understood the importance of public relations and keeping abreast of collectors’ interests.

Barthé mingled with the bohemian circles of downtown Manhattan. Initially unable to afford live models, he sought and found inspiration from on-stage performers. Living downtown provided him the opportunity to socialize not only among collectors but also among artists, dance performers, and actors. His remarkable visual memory permitted him to work without models, producing numerous representations of the human body in movement. During this time, he completed works such as Black Narcissus (1929), The Blackberry Woman (1930), Drum Major (1928), The Breakaway (1929), busts of Alain Locke (1928), bust of A’leila Walker (1928), The Deviled Crab-Man (1929), Rose McClendon (1932), Féral Benga (1935), and Sir John Gielgud as Hamlet (1935).

In October 1933, a major body of Barthé’s work inaugurated the Caz Delbo Galleries at the Rockefeller Center in New York City. The same year, his works were exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. In summer 1934, Barthé went on a tour to Paris with Reverend Edward F. Murphy, a friend of Reverend Kane from New Orleans, who exchanged his first class ticket for two third-class tickets to share with Barthé. This trip exposed Barthé to classical art, but also to performers such as Féral Benga and African American entertainer Josephine Baker, of whom he made portraits in 1935 and 1951, respectively.[

During the next two decades, he built his reputation as a sculptor. He was awarded several awards and has experienced success after success and was considered by writers and critics as one of the leading “moderns” of his time. Among his African-American friends were Wallace Thurman, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, Jimmie Daniels, Countee Cullen, and Harold Jackman. Ralph Ellison was his first student.

Supporters who were white included Carl Van Vechten, Noel Sullivan, Charles Cullen, Lincoln Kirstein, Paul Cadmus, Edgar Kaufmann Jr., and Jared French.

In 1945, Barthé became a member of the National Sculpture Society.

Blackberry Woman, modeled by 1930, cast 1932, bronze, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 2001.6

Later Life

Booker T. Washington, 1946, National Portrait Gallery

Eventually, the tense environment and violence of the city began to take its toll, and he decided to abandon his life of fame and move to Jamaica in the West Indies in 1947. His career flourished in Jamaica, and he remained there until the mid-1960s when ever-growing violence forced him to move again. For the next five years, he lived in Switzerland, Spain, and Italy, then settled in Pasadena, California in a rental apartment. In this apartment, Barthé worked on his memoirs, and most importantly, editioned many of his works with the financial assistance of actor James Garner until his death in 1989. Garner copyrighted Barthé’s artwork, hired a biographer to organize and document his work, and established the Richmond Barthe Trust.

Haitian works

Barthe’s Haitian works came in a time after his 1950 move to Ocho Rios, Jamaica, and were among his larger and more famous works. The huge 40-foot equestrian bronze of Jean Jacques Dessalines, (1952), was one of four heroic sculptures commissioned in 1948 by Haitian political leaders to mark independence celebrations. The Dessalines monument was part of a larger 1954 restoration of the Champs-du-Mars park in Port-au-Prince, Barthe’s 40-foot-high Toussaint L’Ouverture statue (1950), and stone monument was positioned nearer the National Palace, and was unveiled in 1950 with two other commissioned heroic sculptures (in the capital and in the north of the county) by Cuban sculptor Blanco Ramos. At the time, one African-American newspaper called the collection “the Greatest Negro Monuments on earth.” [ L’Overture was a subject Barthe returned to several times, having created a bust (1926) and painted portrait (1929) of the figure early in his career.[

Exhibitions

Barthé’s debut as a professional sculptor was at The Negro in Art Week exhibition in Chicago in 1927. His first solo exhibition was held at the Women’s City Club in Chicago in 1930, exhibiting a selection of 38 works of sculpture, painting, and works on paper.[23] In 1932, the Whitney Museum of American Art decided to purchase a bronze copy of the Blackberry Woman (1930) after exhibiting it at the opening exhibition of Contemporary American Artists in 1932. Barthé’s work was paired with drawings by Delacroix, Matisse, Laurencin, Daumier, and Forain at the Caz-Delbo Gallery in 1933 in New York City.[ In 1942, he had an exhibition of 20 works of art at the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago.] The retrospective which included works from private collections shown for the first time, Richmond Barthé: The Seeker was the inaugural exhibition of the African American Galleries at the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art in Biloxi, Mississippi, curated by Margaret Rose Vendryes, PhD.

Barthé’s most recent retrospective, titled Richmond Barthé: His Life in Art, consisted of over 30 sculptures and photographs.[ The exhibition was organized by Landau Traveling Exhibitions of Los Angeles, CA, in 2009. The exhibition venues included the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, the California African American Museum, the Dixon Gallery and Gardens,] and the NCCU Art Museum.

Save the Date

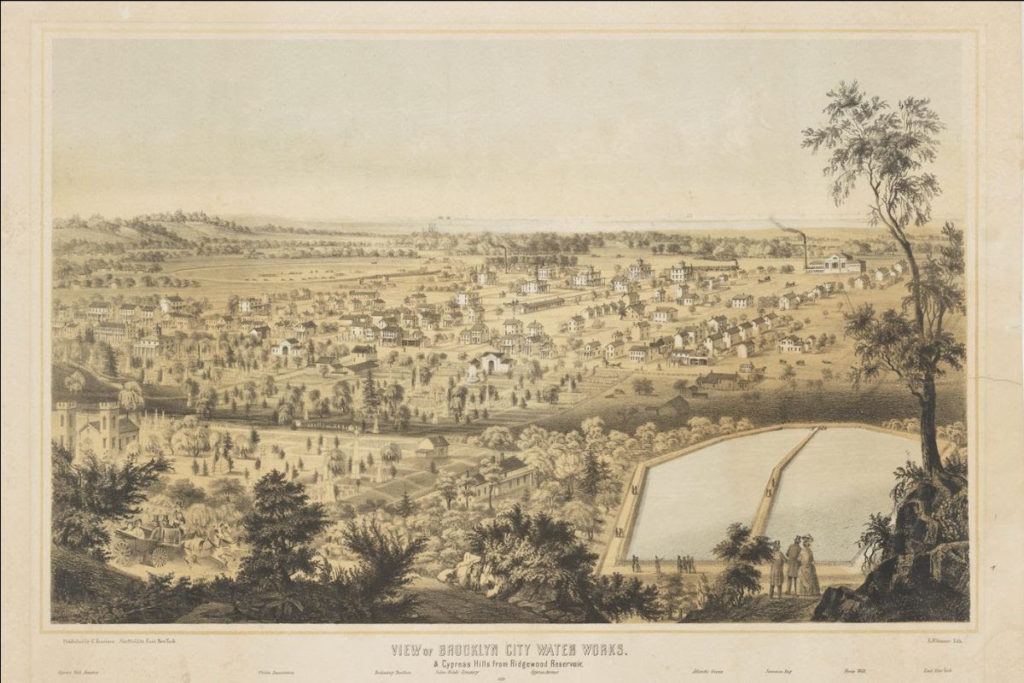

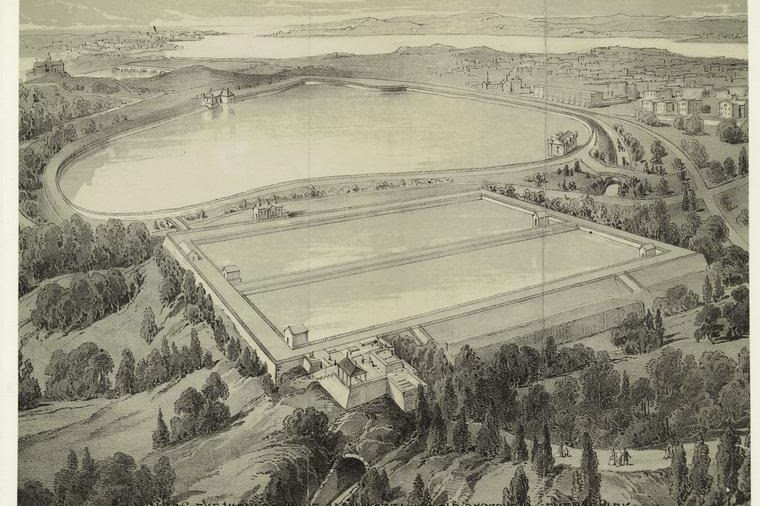

A Tale of Two Waterworks

Talk by Jeffrey Kroessler

presented as part of NYC H20’s Ridgewood Reservoir for the 21st Century

Tuesday, Mar 2, 2021 6:00pm–7:15pm

In conjunction with the current Community Partnership Exhibition Ridgewood Reservoir for the 21st Century situated around the historic Watershed Model at the Queens Museum,

We are pleased to host A Tale of Two Waterworks, talk by Jeffrey Kroessler presented by NYC H20. The presentation will be followed by Q&A with attendees.

This event will take place on Zoom.

To join please see queensmuseum.org

The history of the water systems of New York City and the once independent City of Brooklyn is not only a story of engineering triumph, but a story about the public spirit. Clean water was essential for economic prosperity, health, sanitation, and municipal growth. When New York reached into Westchester and the Catskills for water sources, and when the City of Brooklyn tapped the Long Island aquifer, what were the environmental, economic and political factors in play? A Tale of Two Waterworks will explore the history of the two water systems, how and why they were built, how they determined the city’s future, and the story behind their unification.

Jeffrey A. Kroessler is the Interim Chief Librarian of the Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He is the author of New York, Year by Year, The Greater New York Sports Chronology, and the forthcoming Sunnyside Gardens: Planning and Preservation in a Historic Garden Suburb.

Image Credits: (black and white image) Drawing with aerial view of the two rectangular-shaped reservoir basins built in NYC in 1842, prior to the construction of Central Park, showing the larger oval-shaped reservoir which would replace them in1858. (color image) Lithograph,1859, showing the original two Ridgewood Reservoir basins in the City of Brooklyn, completed by 1858.

MONDAY PHOTO

Send your entry to ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEEKEND PHOTO

Roman Aqueduct – Caesarea Maritima, Haifa, Israel

ARLENE BESSENOFF AND ANDY SPARBERG GOT IT RIGHT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

Sources:

WIKIPEDIA

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM

BROOKLYN NEWS

QUEENS MUSEUM

JUDITH BERDY

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS

CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment