Tuesday, February 23, 2021 – It is not a junkyard, but a treasury of maritime history

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2021

The

294th Edition

From Our Archives

WHERE DO SHIPS

GO TO DIE?

STATEN ISLAND

STEPHEN BLANK

MARITIME ARTIST

JOHN NOBLE

NOBLE MARITIME MUSEUM

Where do ships go to die?

Staten Island!

Stephen Blank

Like the fabled elephant graveyards, ships also have graveyards. Would you believe that there’s a ship graveyard on Staten Island? Read on.

Now let’s be clear. We’re not talking about ship breaking. Ship breaking is where large ocean going ships’ last voyage ends running up on a beach. The vessels are broken up for parts, which can be sold for re-use, or for raw materials, chiefly scrap. Most of this takes place today in India, Bangladesh, China and Pakistan, and much of the breaking up is done by hand –although in much of the 19th century, ship breaking took place mainly in the US and Great Britain.

In previous times, other uses were found for no longer useful ships. In South Street Sea Port in colonial times, old ships were used as fill to extend the shoreline. And Vikings and Egyptians, whose great leaders were entombed with boats. And less glam: Ships (and subway cars, too) have been deliberately sunk off shore to create new reefs.

A ‘graveyard’ for ships is an official dumping site for obsolete watercraft. The ‘graveyard’ is the location where the vessels, or their remains, have been deliberately abandoned. The Staten Island boat graveyard is a marine scrapyard located in the Arthur Kill in Rossville, near the Fresh Kills Landfill, on the West Shore of Staten Island.

When a ship reached the end of its operational life, it could be brought here to the highly industrialized Arthur Kill, sunk in shallow water of the Rossville Boatyard and left to rust away. The Rossville Boatyard is a graveyard of decommissioned, scrapped, and abandoned ships of various sizes, ages, and states of decay and has been recognized as an official dumping ground for old wrecked tugboats, barges and decommissioned ferries.

The Boatyard is known by other names including the Witte Marine Scrap Yard, the Arthur Kill Boat Yard, and the Tugboat Graveyard.

NOAA Nautical Chart 12331: Raritan Bay and Southern Part of Arthur Kill

A word about the Arthur Kill

The Arthur Kill (also known as the Staten Island Sound) is a tidal strait (like the East River) between Staten Island and Union and Middlesex counties in New Jersey and a major navigational channel of the Port of New York and New Jersey. The name is an anglicization of the Dutch achter kill meaning back channel, which refers to its location “behind” Staten Island and takes us back to the early 17th century when the region was part of New Netherland.

During the Revolutionary War, the Kill was the border between British occupied (and fiercely loyalist) Staten Island and New Jersey, held by Washington’s revolutionary troops. Skirmishing and larger battles took place across the Kill. A paragraph from Abandoned New York: Staten Island “was a loyalist stronghold, warmly greeting British troops upon their arrival. Hundreds of islanders enlisted in the British army as the conflict escalated. George Washington himself called the Staten Islanders “our most inveterate enemies.” John Adams was less generous, labeling them “an ignorant, cowardly pack of scoundrels, whose numbers are small, and their spirit less.”

BLAZING STAR TAVERN

BLAZING STAR CEMETERY

AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL ZION CHURCH

OYSTER SHUCKERS AT WORK

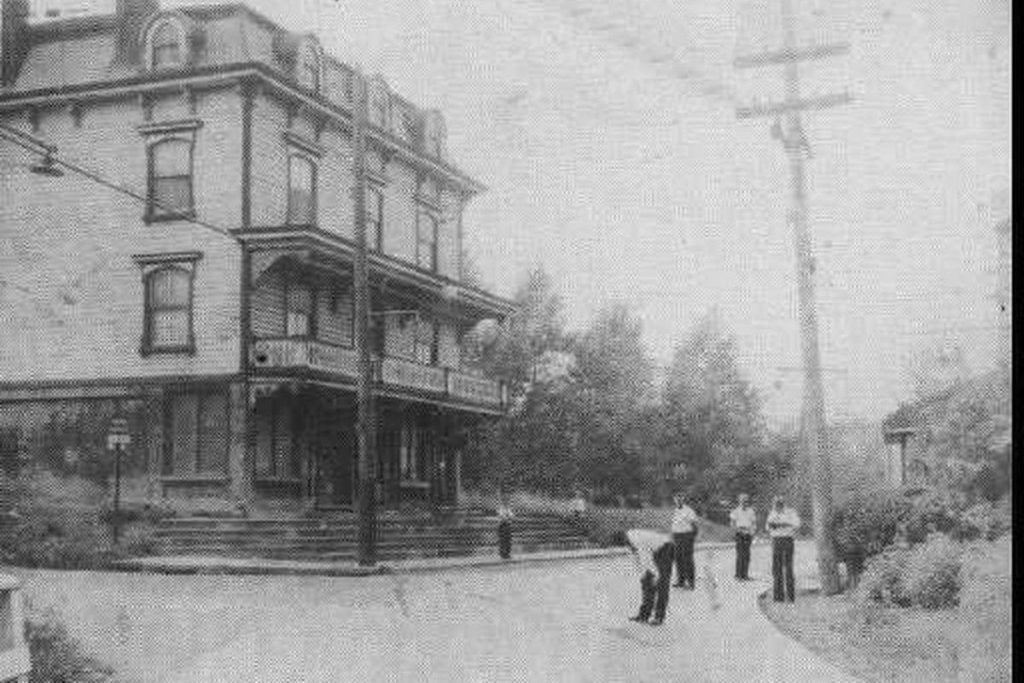

An early settlement on Arthur Kill was named Blazing Star, after a local tavern. Ferries, and later steamships whose wrecks are still sinking in the Arthur Kill, connected it with New Jersey. The Blazing Star Burial Ground, a cemetery dating from the mid-1750, is found just off Arthur Kill Road. In the early days farming flourished and travelers came to take the ferry and stay at a few local hotels, creating a bit of a resort community. The Old Bermuda Inn, built in 1814, still survives.

During the early 1800s, Blazing Star’s name was changed to Rossville, in honor of landowner Col. William E. Ross. He famously built a replica of England’s Windsor Castle on the coast. It was first known as the Ross Mansion or Castle, then became the Lyon Mansion or Castle, when the home was sold to Gov. Caleb Lyon, a poet, author, and member of the New York State Senate and House of Representatives. The building was demolished 45 years after his death in 1875.

In 1827, slavery in New York was abolished. Soon after, freed black slaves began to arrive in Rossville from Virginia and Maryland. They started an oystering village on the Arthur Kill and named their community Sandy Ground, because of the soil found there, leading to strawberry crops. By 1850, the freed men founded the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, which is known to have been an essential stop on the Underground Railroad. (It became a New York City landmark on Feb. 1, 2011.)

Beside Blazing Star Burial Ground is our boatyard burial ground, filled with deteriorating ships from the past.

https://ny.curbed.com/2018/6/21/17124140/staten-island-new-york-arthur-kill-boat-graveyard-photos

The Boatyard

An article in Forgotten New York notes, “Vessels from all decades of the 20th Century lie, not exactly in state, but in a state of decomposition and rust at this former boatyard at Arthur Kill Road and Rossville Avenue….The former piers have collapsed and are for the most part impassible, which makes them a magnet for daredevil urban explorers.”

The Boatyard was founded in the 1930s by John J. Witte and managed by him until his death in 1980. It was then taken over by his son-in-law, Joe Coyne, who described it as similar to an automobile salvage yard, with the boats serving as a source of parts to sell. As of 2014, its official name is the Donjon Iron and Metal Scrap Processing Facility.

Over the last century, Witte Marine dismantled hundreds of ships that once crowded the bustling piers of New York’s coastline. Business seems to have boomed after World War II as many old and battered ships were purchased for deconstruction. But even with a steady stream of salvage work, many old tugboats and smaller harbor ships accumulated on the shores of Arthur Kill and rotted in shallow water.

Some of the vessels here were historic, and the boatyard has been called an “accidental marine museum.” These included the American submarine chaser USS PC-1264, the first World War II US Navy ship to have a predominantly African-American crew; and the New York City Fire Department fireboat Abram S. Hewitt, which served as the floating command post at the 1904 sinking of the passenger ferry P S General Slocum, a disaster that killed more than a thousand people.

A 1990 New York Times story reported that 200 ships were sharing space in the Tugboat Graveyard. Today, there are fewer, each a jumble of broken beams and rusted metal. Over time, all the useful parts have been stripped or stolen.

Apparently, less can be seen today. But photographer Shaun O’Boyle, known for his work on Antarctica, produced a wonderful set of photos of the Ship Graveyard. See his “Modern Ruins: Portraits of place in the Mid-Atlantic Region” (2010), and online at https://www.oboylephoto.com/portfolio/G0000nvLhs57vUko

Portraits of Place

Stephen Blank

RIHS

February 20, 2021

https://ny.curbed.com/2018/6/21/17124140/staten-island-new-york-arthur-kill-boat-graveyard-photos

JOHN A . NOBLE

MARITIME ARTIST

(1913-1983), Self Portrait, Lithograph, Edition 20, 1951 The Noble Maritime Collection, Gift of the Noble Family

John Alexander Noble (1913–1983) was an artist known for creating drawings, paintings, and lithographs of ships and harbors around New York City.

Noble was born in Paris, France, in 1913. The son of painter John Noble, he moved to the United States with his family in 1919. About 1929, he started drawing and painting. While in school he was a “permanent fixture” on the McCarren line tugs, which towed schooners in New York Harbor. In the summer, he would go to sea. In 1931, he graduated from Friends Seminary and returned to France, where he studied for a year at the University of Grenoble and met his wife, Susan Ames. When he returned to New York, he studied for a year at the National Academy of Design.

Career From 1928 to 1945, Noble worked as a seaman on schooners and in marine salvage in New York Harbor. When he saw the Port Johnston Coal Docks on the Kill van Kull, which had become a “great boneyard” of wooden sailing vessels, the sight of it “affected him for life”. In 1941, he began to build a floating, “houseboat” studio there, made out of salvaged ship parts. From 1946, he worked as an artist full-time, voyaging through New York Harbor in a rowboat and creating—in oil paintings, charcoal drawings, sketches and lithographs—a “unique and exacting record” of the “characters, industries, and vessels” of the harbor.

Houseboat Studio

Permanent exhibition in the John A. Noble Maritime Collection at Sailors Snug Harbor

The centerpiece of the museum is Noble’s Houseboat Studio. The studio had been restored to its appearance in 1954, the year Noble and the studio were featured in the December issue of National Geographic. Noble created paintings, drawings, and lithographs there for over 40 years.

Of his “little leaking Monticello,” Noble wrote in 1977, “Strange cabin! and odd its beginnings—and lonely its long and precarious career. Through it all, our tenuous careers, its and mine, have been intimately and inexorably linked, for within its teak walls most of my pictures have been clumsily breech birthed for nigh unto forty years with great effort and small grace….

“After the Civil War, Newark Bay was bridged by the New Jersey Central Railroad. One of the results of this engineering was that anthracite coal came to the banks of the Kill van Kull; and … the world’s greatest hard coal complex—Port Johnston….Well, after a fire sometime in the early twenties…its docks became…a great boneyard.

“I first laid eyes on these acres of new, old, and dead vessels as a boy in 1928 from the deck of a stone schooner….I must say the sight affected me for life—and shortly thereafter I was drawing them….Well, it was but a few years more, and I was making my living there, keeping the vessels which had not yet sunk pumped out and watching their lines….

“Now this great length of pier was punctuated by odd cabins that had been thrown aside in wrecking operations. One of these was the teak saloon of a European yacht. One summer day when things were slack I had a sudden impulse. I cut a hole in its roof and fashioned a makeshift skylight. Through the years I rebuilt and collected teak fittings—adding, changing. Unknown to me was how much I was becoming wedded to my cabin studio. The shock to me was deep when the dock, already badly collapsing, was abandoned, and in panic I built the wooden barge which enabled me to escape from the boneyard. For years now I have been plagued with ‘Oh! the artist with the floating studio, etc. etc.’ There is no cuteness nor color in all this for me—the only small romance is that I did escape.

“The sources of the myriad parts that such a structure must have may seem peculiar now, for they came from that dim region where nothing is ever bought or stolen. The spikes in my bottom were pulled from the deck of the steam schooner Robert Dollar….Most of the planks in the bottom came from the wings of an old Bethlehem Steel Brooklyn dry-dock….The Romanesque windows are black walnut and came from the old Carteret Ferry….The main skylight windows (on the opposite side) are from the classroom built aboard the four-masted schooner Guillford Pendleton….The intriguing little fiddle block and the small davit are from the Kaiser’s sailing yacht Meteor….here also are parts from the steam lighter McKeever Bros.—that carried New York’s dead horses to the rendering plant—the Hart’s Island, that bore the poor and unknown dead to Potter’s Field—and the William C. Moore, the immigrant barge from Ellis Island….

“Time naturally flowed on as did the tides around me. To my port arose the largest oil still in the world, making Getty the richest man in the world, yet in time it rusted and was torn down. To my starboard…a great rack for car tows slowly went into obsolescence…. Dockbuilders, a dredging company, a shipyard came and went,…the nickering vandalism of Sailors’ Snug Harbor trustees never ceased as architectural gems and noble trees came down…until even the seamen were gone. It strikes me as weird that this stone was no sooner finished than the last of the great hulks of the boneyard burned to the water’s edge.

“Thus it came about that now my own little leaking Monticello pitches and survives in the wake of the passing tugs.” John A. Noble Essays, 1977

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR SUBMISSION TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

HUDSON YARD “&” TRAIN ENTRANCE

LAURA HUSSEY, GLORIA HERMAN & VERN HARWOOD & ANDY SPARBERG

GOT IT!

From our transit expert Andy Sparberg, some clarifications of Monday’s issue:

In 1945 the Transit Authority NYC Board of Transportation shut down the City Hall Station, demolishing the ornamental kiosks and sealing the entrances under concrete slabs. The tiled arches and brass chandeliers were thrust into tomb-like darkness and the station was essentially forgotten. However, Lexington Ave. Local (#6 today) trains continued to use the station’s loop tracks to change direction at Brooklyn Bridge, and do so to this day, as noted in the last sentence.

Any hope that the City Hall stop would be resurrected was smashed when modern train cars became too long , the R17s, introduced on the IRT in 1954, had door positions that could not safely open on the sharp curve of the platform. The wide gaps created between the platform and cars would be unsafe and logistically unreasonable to attempt to correct.

Explanations: The Transit Authority was not created until 1953. The older model cars had doors at the extreme car ends, whereas the R17 cars were the same length, 51 feet, but had a different door arrangement that created dangerous gaps on curved platforms.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

Sources

Wikipedia

SAILORS SNUG HARBOR

JOHN NOBLE MARITIME COLLECTION (C)

All image are copyrighted (c)

Roosevelt Island Historical Society

unless otherwise indicated

PHOTOS BY JUDITH BERDY / RIHS (C)

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS

CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment