Tuesday, August 3, 2021 – Many ideas were floated to re-build our iconic bridges

TUESDAY, AUGUST 3, 2021

The

431st Edition

From the Archives

Across the East River:

The Other Bridges

Stephen Blank

Let’s talk about East River bridges. We all know something about the Brooklyn Bridge and I have written about our Queensboro Bridge. But perhaps we can bridge some information gaps about other East River crossings.

First, how many bridges cross the East River? Seven? No, eight. (Don’t forget Hell Gate Bridge.) Three older bridges south of us (the BMW – Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg), Oueensboro, and then north, towards Long Island Sound – Hell Gate and Robert F. Kennedy, Bronx Whitestone and Throgs Neck.

Second question. Which of these bridges was viewed as the ugliest? Manhattan, Williamsburg and Queensboro – but never Brooklyn – have all been awarded that dubious honor at one time or another. Williamsburg is still considered the “Ugly Duckling” of suspension bridges, but the dysfunctional problem child is Manhattan. And, our cantilever truss, Queensboro, has been termed ungainly and visually heavy. Henry Hornbostel, responsible for the ornamental decoration on the towers and portals, has been widely quoted as saying, upon seeing the completed bridge “My God, it’s a blacksmith’s shop!”

Yet wonderful. Long ago, in 1916, Ellsworth Huntington, a well-known Yale geographer, gushed over our bridges and the City that built them: “With the exception of the bridge over the Firth of Forth in Scotland, New York has the four longest bridges in the world, their length varying from 6,000 to 7,500 feet… The New York bridges, too, have some of the longest spans in the world. Among suspension bridges, the Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Williamsburg Bridges…are unrivaled. The Hell Gate Bridge…is the largest arch bridge in existence… It is an astonishing fact that of the world’s seven largest bridges five should be in the midst of the world’s largest city.”

Also astonishing – how quickly they were built. Brooklyn, completed 1883; Williamsburg, 1903; Queensboro, March 1909; Manhattan, December 1909; and Hell Gate, 1916. These were among the largest and most complex – and most expensive – engineering jobs ever undertaken. Remember, too, that at this moment the City was raising the new sky scrapers, creating many of our great Beaux Arts edifices, and building the subways. In the 1890’s, much of the city was being wired for electricity. And New York’s population was increasing from just under 2 million in 1880 to almost 5 million in 1910.

We don’t know much about who actually worked on the bridges. Except, not Mohawks, who worked on many sky scrapers only from the 1920s. Many workers must have been immigrants whose number in the city increased from about half a million in 1880 to 2 million in 1910. (Soon, at the peak of immigration, some 40% of the City’s population would be immigrants.)

I learned preparing an earlier essay (“Thomas Rainey: A Man and a Bridge”) that discussions about a bridge crossing the East River over Blackwell’s Island had been on- and off-going since the 1850s, and were quite serious in the 1880s, but to no avail. So, of course, Brooklyn was first, and was the longest suspension bridge in the world.

Williamsburgers, too, pushed for a connector to Manhattan, even before Brooklyn opened. Why Williamsburg? Williamsburg stood apart from the rest of Brooklyn. Indeed, between 1852 and 1855, Williamsburg (or Williamsburgh, its original spelling) was its own city, comprised of the modern neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Greenpoint. In 1855 it was absorbed — along with the Town of Bushwalk — into the expanding city of Brooklyn and these new additions, more industrial and immigrant in nature, were referred to as the Eastern District.

But, as with the Queensboro idea, bottom up pressure, even from the business community, was insufficient. A new organization, the East River Bridge Company, was able to get a charter from New York State to build two bridges to form a loop transit line connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan. But the project proceeded slowly. Others then pushed ahead for a bridge that would be owned by the two cities, ultimately purchasing the Company’s rights for $200,000. And the loop design was dropped. As usual, New York politics intervened and successive NYC mayors fired and hired commissioners and engineers in the bridge project.

What began as a design similar to Brooklyn worked out to be something much different, with all-steel towers that never won the hearts and minds of New Yorkers, and seems to lack the charm and grace of Brooklyn.

1896 tower, main and approach span detail. https://www.structuremag.org/?p=10998

On the Manhattan side, planners used the project to clear away a notorious districts – Corlears Hook, where shipbuilding had been concentrated and now a well-known red light district. (The ladies there were known as “hookers”, a much better story than the conventional one about Civil War General Joseph Hooker.)

The Bridge opened up space in less populated Brooklyn for those, many Jews, who inhabited the very crowded Lower East Side. Thus the bridge was even called the “Jews Highway” as those of Eastern European and Russian Jewish heritage transplanted to Williamsburg.

But perhaps the most intriguing part of the story is the makeover proposed by Donald Trump in the 1980s. Williamsburg would be redone a “spectacular landmark”.

The fact is that Williamsburg was in bad shape. In May 1987, a six-foot beam fell from the bridge into the East River; in April 1988, the bridge was abruptly closed for two weeks after corrosion was found that presented a “5 percent chance there would have been a failure” of the bridge.

Trump’s plan included covering it with bronze reflecting panels and adding a two-story restaurant on one of the towers.

By 1898, electric trolleys, an El train and pedestrian lanes were crossing the Brooklyn, leaving only one lane in each direction for all other traffic. It is said that a traffic jam in 1898 was so bad the weight on the bridge caused it drop 12 feet, and engineers were afraid that if traffic was not reduced, it would fall. It was obvious that another bridge was needed from downtown Manhattan to the busy Fulton Ferry area.

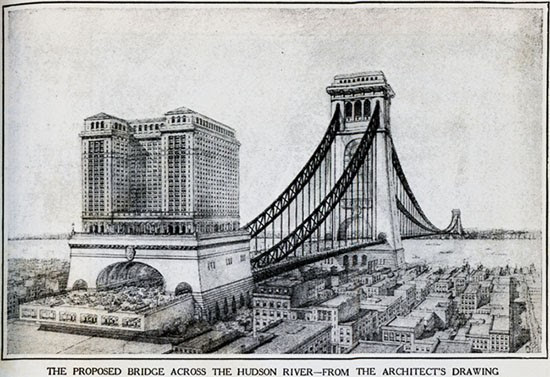

In 1901, planning began for the new bridge, called Bridge No.3. Seth Low, reform mayor elected to counter Tammany influence and graft, hired Gustav Lindenthal, a respected bridge engineer and architect to design what would be the Manhattan Bridge. Lindenthal had grand plans for an enormous bridge with 14 lanes of track, as well as towers large enough to hold auditoriums.

In accordance with the City Beautiful Movement, plans included large public plazas leading to the bridge from both sides, very grand Baroque style with a gleaming triumphal arch and colonnade on the Manhattan side and sedate but impressive portal with statues on the Brooklyn side. The Manhattan entrance, inspired by Paris’ Porte St. Denis arch and Bernini’s Colonnade at St. Peter’s in Rome, had a colored mosaic walkway within a large plaza leading to the bridge.

But before plans could be implemented, Low’s term ended and the Tammany machine installed George McClellen as mayor. McClellen appointed a political hack named George Best as Chief Engineer, who was not an engineer or even an architect, who immediately fired Lindenthal, and hired a Leon S. Moisseiff to complete the bridge.

Moisieff’s design envisioned a lighter and shallower stiffening truss. The bridge is braced in only two directions, allowing the towers to flex, reducing bending moments and requiring smaller foundations under the tower. He also put the subway and streetcar tracks on the outer edges of the roadway, instead of in the middle, as in the both of the other East River bridges. This stressed the bridge, so when trains were coming from both directions, it sway and twist – a problem that worsened with longer trains. And, as one bridge historian writes, “Because it was a Tammany Hall project, a whole lot of money had to be spread around, and the bridge, which was supposed to cost under $20 million ended up at $31 million by the time it was finished. Initially, that is. In reality, the bridge would become a massive black hole sucking money into its maw well into the 21st century.”

The bridge was constructed in record time, mostly so that McClellan could claim it under his administration, and it had a show opening, on December 31, 1909, the last day of his term. Since the road wasn’t finished, they laid temporary planks across the deck to enable vehicles to cross. The pedestrian walkway wasn’t finished until 1910, and the first trains crossed in 1912. The Beaux Arts entryways to the bridge weren’t completed until 1916.

In 1961, Robert Moses wanted to demolish the Manhattan entrance to the bridge in his plans for a Lower Manhattan Expressway that would connect the Manhattan Bridge and the Holland Tunnel. He got the permission of the New York City Arts Commission to do so, but the roadway was never built. The furor over this decision was a factor in the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Commission a few years later.

Most of the park leading to the bridge was reclaimed by the building of Confucius Plaza in the 1960’s. As Christopher Gray says in a “Cityscape” article in the NY Times in 1996, “Today the plaza of the Manhattan Bridge evokes not the City Beautiful but the sack of Rome.”

Bridges, love them or hate them, we can’t live without them.

Stephen Blank

RIHS

August 1, 2021

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY SEND TO ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

THE WONDERFUL BROOKLYN BRIDGE PARK THAT GENTLY FLOWS TO THE RIVERFRONT.

A CONTRAST TO OUR SOUTHPOINT WHERE THE RIVER IS MANY FEET BELOW.

NINA LUBLIN, ED LITCHER, OLYA TURCHIN, HARA REISER, ALEXIS VILLAFANE

ALL GOT IT RIGHT!!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

STEPHEN BLANK

Sources

https://gothamist.com/arts-entertainment/the-12-best-bridges-in-nyc

https://oldstructures.nyc/2018/03/22/sometimes-an-ugly-duckling-becomes-an-ugly-duck/ https://www.structuremag.org/?p=10998 https://newyorkled.com/williamsburg-bridge/ https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2018/01/construction-williamsburg-bridge-history-behind-scene-alienist.html https://www.brownstoner.com/brooklyn-life/walkabout-the-m/Ellsworth Huntington, “The Water Barriers of New York City,” Geographical Review, Sept., 1916

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS

CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment