Monday, September 19, 2022 – THE VALUE OF SILK WAS SO GREAT, SPECIAL TRAINS RUSHED IT EAST

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2022

THE 787th EDITION

THE SILK

TRAINS

THAT RUSHED

ACROSS AMERICA

&

WHO WAS

SPENCER TRASK

The Silk Train That Killed Financier Spencer

Trask

| On the morning of December 31, 1909, Saratoga Springs philanthropist and financier Spencer Trask was just waking up after a night in a railroad sleeping car at the rear of the Montreal Express. The night before this southbound train had picked up Trask in Saratoga as it made its way toward New York City.At 8:03 am, only moments after the express train had stopped unexpectedly on the mainline near Croton, Westchester County, New York, a train transporting bales of raw silk crashed into its rear, killing Trask, the porter in his sleeping car, and injuring several other of the passengers. While the direct cause of this deadly wreck pointed to a failure of signal equipment and railroad personnel, events leading up to the tragedy had been put into motion six thousand miles to the west seventeen days earlier.Silk was a commodity whose value in North America had increased dramatically in the years following the Civil War. In 1909, the year of Spencer Trask’s death, our country consumed half of the world’s production of raw silk, about twenty-four million pounds, with an estimated value of eighty million dollars.After silk was harvested in Japan, it was packaged into three-foot bales weighing just under two hundred pounds. The bales were sealed, wrapped in heavy paper, and then marked for shipment throughout the world. In the middle of December of 1909 at the Japanese port of Yokohama, a fast steamship of the Canadian Pacific Railroad’s Empress Line was loaded with the bales of raw silk that twelve days later would be on the silk train that ended Trask’s life.The destination of this vessel was Vancouver, British Columbia, where within minutes of docking bales of raw silk were streaming down a conveyor belt and into the hands of an army of stevedores whose sole duty was to quickly fill the waiting railroad freight cars. In less than two hours, over one million dollars of silk bales were in place and the journey across Canada began.Special silk trains transported this valuable cargo from Pacific Ocean ports to the National Silk Exchange in New York City. The train’s freight cars were specially made for moving this valuable product with both safety and speed. Built on passenger car suspension and wheels, they were shorter than the standard freight car to allow them to take curves at higher speeds. They were also lined on the inside with varnished wood and airtight as the value of the raw silk diminished if it was allowed to absorb moisture.From Vancouver, the train headed east to Prescott, in Ontario, Canada where the cars were taken across the St. Lawrence River to Ogdensburg on the Canadian Pacific Railroad ferry Charles Lyon. From here, the freight cars were attached to a New York Central engine and started south through upstate New York. Five days after coming off the boat from Japan, these valuable bales of raw silk were expected to arrive in New York City.Speed was of the essence in these trips for several reasons, some practical and others clearly financial. The most important of these was the high cost of insurance and bonding that the railroad took out on each shipment which amounted to thousands of dollars a day, often calculated by the hour. There also was the practical matter of the safety of the train and the silk it carried. The railroad looked at each trip as traveling through what they called “a zone of danger” as it passed from point A to point B, with the solution being to travel as quickly as possible. For the silk train, it meant often moving at speeds more than eighty miles an hour with only periodic stops for water and to change out the hard-working steam engines and crews.To expedite these trains, they were put through as a Special, a designation that required all other trains to move aside. These trains were on no schedule, they left Vancouver whenever a ship arrived and then moved as quickly across the continent as conditions allowed. The August 19, 1911, edition of the Plattsburgh Press gave this account of one of these runs:“A million-dollar silk train of eight cars was rushed to Prescott Thursday night after a record-breaking run of four days from Vancouver and no time was lost in getting the cargo ferried across to Ogdensburg where a fresh engine was waiting to rush the valuable cargo down to New York in eighteen hours.”On January 3, 1910, just days after the accident, the Ogdensburg Journal ran a story that suggested that the Canadian Pacific silk train that caused Spencer Trak’s death was in a race to New York with the Union Pacific Railway. It was said that the winner would be given preference in future shipments of raw silk. Harper’s Weekly Magazine in a story that they published on December 4, 1909, reported that winning these contests was “the one important thing to these otherwise unemotional railroad men,” and that they would do everything possible to cut even a few minutes off the time it took to move these trains along their route.No changes concerning the racing of silk trains were ever made after this tragic accident, and the only reported penalty to the railroad was a sixty-thousand-dollar lawsuit that his widow donated to Saratoga charities. By the 1930s the silk trains had been discontinued, due to the dramatic drop in the value of raw silk, and the development of manmade fibers. |

The Life and Legacies of Spencer Trask

BY JIM RICHMOND | SPONSORED BY THE SARATOGA COUNTY HISTORY ROUNDTABLE | HISTORY

Spencer Trask awoke on the morning of December 31, 1909 in the last compartment of the last sleeper car on the Montreal Express as it neared New York City on the D&H Railroad line. Getting dressed, his thoughts may have turned to the three passions that dominated his life of 65 years. He did not know then that it would the final day of his eventful life.

Trask was born in 1844 in Brooklyn, the son of Alanson Trask and Sarah Marquand Trask. His early years were immersed in his first passion, to become a successful businessman like his father. Alanson Trask was a New Englander of Puritan stock, descended from a family that arrived in Massachusetts in 1628. Two centuries later, Alanson became the first of the family to move away, settling in New York City. The Trasks were a prominent family of some means, but Alanson took their fortunes to a new level. Investing in a shoe manufacturing business during the Civil War, he became an overnight multi-millionaire by today’s standards, selling shoes and other goods to the Union Army.

Son Spencer entered Princeton in 1862, and upon graduating 4 years later entered the investment banking field. Focusing first on providing venture capital funds to the idea men of the post-Civil War era, he had an uncanny ability to pick winners, most famously backing unknown inventers, such as Thomas Edison. Later he and his firm, Spencer Trask & Co., took on the challenge of rescuing struggling businesses. About to go under, he was among the financiers that saved the New York Times from bankruptcy, becoming President of the newspaper from 1897 to 1906.

By that time, his fortune made, he could indulge his other passions. In 1874 he had married Kate Nichols, daughter of another elite New York family, whose own passions centered around the cultural and literary world. That partnership was to bear fruit in later years. The Yaddo Corporation, first conceived by the Trasks in 1900, opens its doors to members of the artistic community after his death. Authors, painters, sculptors and musicians availed themselves of that restful retreat located in the woodlands near the Saratoga racecourse.

For Spencer and Kate Trask, the decade of the 1880’s was filled with both joy and sorrow. In 1880 their first child, Alanson, named after his grandfather, died at the age of five at their Brooklyn home. Distraught, they made a life changing decision to seek a peaceful place in the country to help them deal with their loss. They were already familiar with the resort town of Saratoga Springs, having visited there during the summer social season. Spencer’s father had retired there and taken up residence in an estate he named ”Ooweekin,” Home of Rest, in the native Iroquois language. In 1881 they leased the former Barhydt estate for the summer. Kate was so enchanted they purchased the 155-acre property for $16,500 the next year. Father and son now owned adjacent retirement estates. Ooweekin was on Nelson Avenue, (later the estate and horse training facility owned by John Hay Whitney), and the soon-to-be named Yaddo on Union Avenue, connected by a road now enveloped by private property south of the NYRA backstretch.

Tragedy struck again in 1888 when daughter Christina and son Spencer, Jr. died of diphtheria they had contracted from their mother Kate, who survived. One year later their fourth child, Katrina died three days after birth. Saddened, but still resilient, they plunged themselves into expanding their estate. When their renovated Queen Anne style home was destroyed by fire in 1891, they immediately set to work to construct the large Gothic style mansion, still the centerpiece of Yaddo today.

During this time, Spencer indulged his third passion – using his resources and influence to address what he saw as the dark side of the Gilded Age. In a town whose life blood was gambling, he railed against it, spending $50,000 and creating his own newspaper, the Saratoga Union to promote his views. When several companies were formed in the 1890’s to extract carbonic gas from the springs – thereby threatening the springs and their park-like surroundings – he swung into action. Trask worked with Governor Hughes to secure passage of the Anti-Pumping Act of 1908, followed by the establishment of the State Reservation in 1909, which was given the authority to purchase the land that was to become the Saratoga Spa State Park.

Trask was appointed to head the three-member commission and it was on Reservation business that he traveled to New York on the last day of 1909. While dressing in his compartment, the train was halted by a signal. A freight train following behind failed to stop and plowed into the passenger train, crushing the last car, and ending the life of this man of many virtues. His legacy lives on in his adopted hometown. Katrina commissioned family friend Daniel Chester French to sculpt the Spirit of Life in Congress Park in his honor, and Yaddo continues to welcome artists to its peaceful grounds.

Jim Richmond is a local independent historian, and the author of two books, “War on the Middleline” and “Milton, New York, A New Town in a New Nation” with co-author Kim McCartney. He is currently researching the early history of today’s Saratoga Spa State Park. Jim is also a founding member of the Saratoga County History Roundtable and can be reached at SaratogaCoHistoryRoundtable@gmail.com

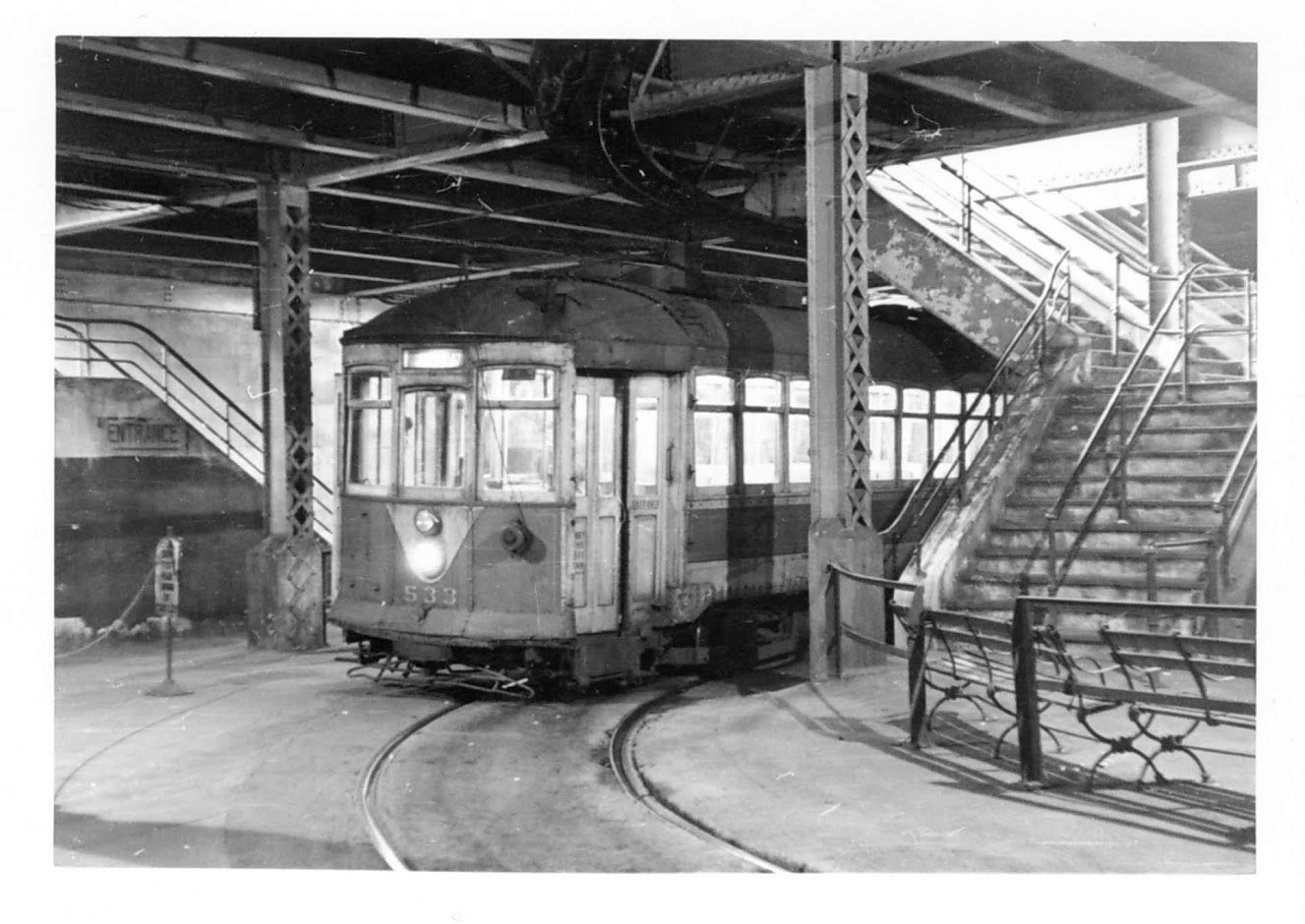

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

Send your response to:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

WEEKEND PHOTO

INTERIOR COURTYARD OF THE

BOSTON CENTRAL LIBRARY

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

NEW YORK ALMANACK

SARATOGA COUNTY HISTORY ROUNDTABLE

GRANTS

CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE JULE MENIN DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment