Thursday, January 26, 2023 – MOST UNPLEASANT STORY OF SHIPS TO THE AMERICAS

FROM THE ARCHIVES

THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 2023

ISSUE 896

MASSACRES & MIGRANTS AT SEA:

DEADLY VOYAGES TO NEW YORK

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Jaap Harskamp

Massacres & Migrants at Sea: Deadly Voyages To New York

January 11, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp

The 1840s brought about a transformation in the nature of transatlantic shipping. With the development of European colonial empires, the forced transportation of African slaves had become big business.

Liverpool was the focus of the British slave trade. As a result of crusading abolitionist movements and subsequent legal intervention, the brutal practice declined there during that decade. But more or less simultaneously a new form of people trafficking took its place.

The flow of destitute migrants from Europe to the United States offered lucrative opportunities for Anglo-American shipping lines. The epoch established the cynical maxim that there is money in misery. Liverpool developed into the main port of departure for countless emigrants on the seemingly endless sea journey to New York. For all too many it proved to be a deadly voyage.

To this day, the image of migrants at sea remains an emotive but unresolved issue that has its roots in “business” models going back as far as the slave trade.

Liverpool & Slavery

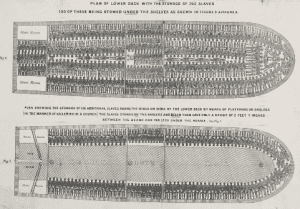

Between 1550 and 1850, approximately twelve and a half million Africans were transported by English ships. Eleven million survivors landed in the West Indies and the Americas, the majority of whom were sold to Brazilian and Caribbean sugar plantations. The others went missing. Liverpool was central to Britain’s involvement. By the heyday of the Atlantic trade, one in six enslaved Africans made their forced journey aboard a Liverpool-registered ship.

In February 1781, with the 4th Anglo-Dutch War in full flow, the English brig HMS Alert captured the slave ship Zorg (meaning: care / caring) which operated from Middelburg delivering kidnapped Africans to the Dutch colony of Surinam to work on its plantations. Renamed rather oddly as Zong, she arrived at the Gold Coast of West Africa later that month where the slaver was purchased on behalf of a Liverpool syndicate led by James Gregson.

By the standard of similar ships, the Zong was small in size and designed to carry just under two hundred slaves. When she sailed from Africa in September 1781 bound for Jamaica, Captain Luke Collingwood had more than doubled the ship’s capacity, carrying 442 slaves in order to maximize profits.

When reaching a corridor near the equator known as “the doldrums” because of intervals of extreme heat and no wind, the ship sat stranded, short of water and food. Driven by the critical state of affairs, Collingwood gave the order that the numbers on board had to be reduced. Crew members threw 142 slaves over the side. On arrival, the insurers refused to pay the claim for compensation. The matter had to be settled in a British court.

The issues of who had committed the atrocity and why were not considered. The central question before the court was if the “lost cargo” was covered by insurance or not. A jury heard the dispute at London’s Guildhall in March 1783 and ruled in favor of the ship owners. The insurers appealed and the case came before Lord Chief Justice Mansfield. The latter rejected the verdict by pointing to new evidence which suggested the Captain and crew were responsible for the tragedy (Collingwood had died three days after his ship reached Jamaica).

Those responsible for the Zong massacre were never brought to justice, but the tragedy exposed the brutality of a trade that reduced African lives to mere items of commerce. Reports of the massacre increased momentum for the abolitionist movement, although it would take another half century before the United Kingdom passed the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

Massacre at Sea

J.M.W. Turner was an outstanding marine painter and many of his canvasses depict storms at sea in which ships are torn apart and sailors struggle to survive. His unfinished “A Disaster at Sea” (c. 1835) was based on a real incident, the loss of the Amphitrite in September 1833.

The ship had sailed from Woolwich, London, bound for New South Wales. On board were over one hundred female convicts and twelve children. Gale-force winds drove the ship on to a sandbank off Boulogne, but the captain refused all rescue offers. The ship broke up and only three people survived. What political system could justify such cruel treatment of women and children?

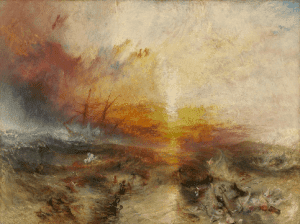

Soon after this attempt, the painter would turn his anger on one of the deep and continuing injustices of his age. In 1840 Turner first exhibited “The Slave Ship” (originally titled “Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying”) at London’s Royal Academy. It depicts a ship at the mercy of a tumultuous sea, leaving scattered human forms drowning in its wake.

The canvas was inspired by the tale of the Zong massacre in Thomas Clarkson’s The History and Abolition of the Slave Trade, the second edition of which had been published in 1839. The 1840 exhibition of the painting coincided with various international abolitionist campaigns (that same year, two anti-slavery conventions took place in London). A public display of this horrific event was intended to evoke a strong response to the barbaric slave trade. A powerful protest, Turner’s painting functioned as a call to political action.

To present-day viewers Turner’s manner of applying Edmund Burke’s concept that connects the Romantic “Sublime” with awe and terror when facing the forces of nature may be over-elaborate, but his contemporaries felt the full impact of this intensely dramatic approach. Abolitionists had found a formidable ally.

Migrant Trade

As the slave trade declined, Liverpool became engaged in another form of people trafficking by which greedy ship owners packed as many migrants as possible in the limited space on board to make spectacular profits. The city opened up the route across the Atlantic for countless European emigrants. It was – in all but name – a new slave trade.

When the influx of Irish migrants hit Liverpool with the start of the potato famine in 1845, an estimated 1.5 million desperate people crossed the Irish Sea heading for the city, three quarters of which then boarded ships to New York, Philadelphia or elsewhere.

Early migrant vessels were nicknamed “coffin ships” because of the horrific conditions on board and the number of people who did not survive the crossings. In 1847, 1,879 immigrants died on the voyage to New York, forcing governments to (reluctantly) impose regulations that would limit fatalities and improve the conditions of travel.

Whilst living in New York in 1818, British merchant Jeremiah Thompson had pioneered the concept of the sailing packet which was guaranteed to depart on schedule rather than (the traditional) waiting until its hold was full. Offering a time table, his Black Ball Line revolutionized the transatlantic trade. British and American merchants joined forces to take full advantage of the migration boom. The Liverpool firm of Caleb Grimshaw & Company, specialists in migration traffic, teamed up as agents for Thompson in 1842 to take charge of the Liverpool to New York route.

Sailing under the “New Line” flag, they secured passengers and freight for the Thompson packets (and many others). By 1845 the company was advertising a dozen or more ships at a time and dispatching them every five to seven days. Having changed the name to “Black Star,” the firm sent out more American migrant ships under their flag than any of its rivals.

Caleb Grimshaw

One of the vessels operated by Grimshaw was the wooden packet ship Caleb Grimshaw (named after the company’s late founder). Built at William Henry Webb’s shipyard in New York and launched in early 1848, she sailed from Liverpool’s Waterloo Dock to New York under command of Captain William Hoxie with a crew of thirty men, carrying a maximum of 427 migrants. Samuel Walters, Liverpool’s leading marine artist at the time, painted a portrait of the full-rigged ship in 1848.

The ship completed a total of five trips before disaster struck on her sixth crossing in November 1849 with 425 migrants aboard. A fire created panic and chaos. A lack of leadership drove some passengers to take matters into their own hands, lowering one of the ship’s boats which crashed into the water. Twelve people were swept away and drowned. Another boat was lowered by the crew, equipped with supplies of food and water for a select number of passengers.

The next morning, with the blaze raging, a boat was reserved for the captain’s wife and daughter who were joined by some of the first-class cabin travelers. Later that day Hoxie himself abandoned ship. The unfortunate migrants in steerage were left behind to fend for themselves, building survival rafts with remaining members of the crew on board.

Help arrived on the fourth day when the trading barque Sarah, sailing from London to Halifax, drew alongside. Her master David Cooke first rescued the passengers on the boats and rafts, leaving more than 250 passengers on board clinging to the burning wreckage. It took a total of ten days to save the last of the survivors and deliver them safely to the port of Flores in the Azores. When the Caleb Grimshaw finally sank, the lives of ninety migrants had been lost.

When news of the rescue spread in New York, Captain Cooke was granted the Freedom of the City and he and his crew shared a reward for their bravery. Although the tragedy caused angry exchanges in the British press, Captain Hoxie escaped official censure for leaving his ship prematurely. Questions were raised in Parliament as to the cause of the fire, but no one was held responsible or further action taken.

Art & Calamity

The pictorial representation of catastrophe in the centuries before the invention of photography took the shape of a visual commemoration of events with a narrative content. The 1666 Fire of London, the 1755 Lisbon earthquake or the 1794 eruption of Vesuvius were all treated in this manner.

More generally, disaster was treated as an allegory, demonstrating man’s insignificance when faced with the terrors of nature. Tiny painted figures face a panorama of atmospheric effects behind which hides the hand of a wrathful God. The might of a turbulent sea was there to remind us of our frailty and impermanence. This is the realm of mythological or Biblical retribution, the seascape of Rembrandt’s “Storm on the Sea of Galilee” (1633). Even the loss of the Titanic was interpreted by some moralists as divine “punishment” for man’s hubris.

Over time artists have paid ample attention to violent phenomena such as armed conflict and warfare. In the seventeenth century grand battles at sea were a favorite theme of marine painters. It was not the suffering of sailors, but the grandiose spectacle of warships in combat that made such paintings popular.

Calamity – and more specifically: calamity at sea is a much rarer theme in art history. There are few painted reminders of disasters in which overloaded migrant ships ran by unscrupulous owners went down with the tragic loss of many lives. Turner’s brush had highlighted the viciousness of the slave trade, but the urgent need to artistically record the maltreatment of migrants was obscured.

Ford Madox Brown’s “The Last of England” depicts a couple of emigrants sailing away from the country. Created in 1855, the artist painted the scene in his Hampstead garden; he himself and his wife posed as “suffering” migrants. Since Turner, public taste had changed. Pain and anguish were covered with a sugar coating of sentimentality; the destructive powers of the elements tamed for domestic use; the troublesome subject of migration was sanitized. Brown’s image has persistently been named one of the nation’s favorite paintings.

The rather pathetic nature of this painting becomes clear when put in the context of real events. On October 1853 the migrant ship R.M.S. Tayleur was launched on the River Mersey. Designed by William Rennie of Liverpool, the vessel was built within six months and chartered by the White Line. She left Liverpool in January 1854 on her maiden voyage with 652 passengers and crew on board. The ship’s master was young and inexperienced; the crew consisted of ill-trained seamen some of whom did neither speak nor understand English.

In poor weather conditions, the ship drifted off course and ran aground on the east coast of Lambay Island, close to Dublin Bay, and sank. An inquest blamed its owners, accusing them of neglect for allowing the ship to depart with faulty equipment (compasses). The number of people who lost their lives in the disaster varies from three to four hundred, depending on source. There were over one hundred women on board. Three survived.

PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR SUBMISSION TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

GIVERNY, THE HOME OF CLAUDE MONET

HARA REISER, GLORIA HERMAN, VICKI FEINMEL ALL GOT IT RIGHT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: diagram (1787) of the Liverpool-launched slave ship Brookes; the vessel is known to have carried 609 slaves at one time; 1782 woodcut of the Zong massacre; The Slave Ship, 1840 by J.M.W. Turner (Tate Gallery, London); The Caleb Grimshaw, 1848 by Samuel Waters; Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633) by Rembrandt; The Last of England, 1855 by Ford Madox Brown (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery).

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment