Friday, March 17, 2023 – HOW TO GET MATERIALS FROM PLACE TO PLACE

FROM THE ARCHIVES

FRIDAY, MARCH 17, 2023

ISSUE 941

Hudson River Towing:

Austin’s Albany & Canal Line

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Hudson River Towing: Austin’s Albany & Canal Line

March 16, 2023 by Peter Hess

Jeremiah J. Austin, Jr. was born in 1819, just 12 years after the first commercial steamboat trip on the Hudson River and two years after construction of the Erie Canal began at Rome, New York. His father Jeremiah J. Austin Sr. was a prominent Albany businessman involved in Hudson River commerce.

After the Erie Canal opened, freight could be transported all the way across the Great Lakes to the entrance to the canal at Buffalo and then along the canal to Albany where it was shipped down the Hudson River to New York Harbor. From there freight could be fairly easily transported to any port on the East Coast, Europe or the Caribbean.

Millions of tons of freight began flowing both east and west along the canal as well as north and south on the Hudson River creating the first major interstate transportation system in the United States. Transporting this freight quickly became a booming business as Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York were now all connected by a water highway.

Many young men saw their opportunity to make their fortune by investing in canal boats. They carried grain, ice and products of all kinds to Albany in canal boats pulled by mules or oxen and then were towed by towboats to the city of New York where they were unloaded. They returned west with manufactured products.

Jeremiah J. Austin, Sr. and his son became involved in transporting freight along this system. They formed the Albany & Canal (A&C) Line shipping company. Their canal boats traveled along the Erie Canal pulled by teams of oxen or mules. At Albany, the freight was unloaded and reloaded onto steam-powered boats or sailing ships (such as frigates or sloops) to continue the trip to New York harbor.

Demand for shipping on the canal was great and Austin sought ways to increase his shipping capacity and shorten the time it took to move freight. He realized that if he could transport his canal boats directly to New York without having to transfer the freight to Hudson River vessels at Albany, he could save a substantial amount of labor and time. His solution was to construct specialized steam powered towboats to pull groups of canal boats.

Jeremiah J. Austin, Jr. commissioned the construction of the side-wheeled steam towboat Austin, which was built at Hoboken, New Jersey in 1853 for the A&C Line. The Austin was one of the first steam-powered towboats actually built to be a towboat; most of the other steam-powered towboats at the time were older passenger boats cut down and converted to towboats. The 197-foot Austin carried two green signal lights forward and two aft, which together with a green walking beam identified her as an A&C towboat.

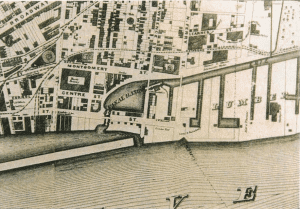

The Austin would tie up at the A&C Line’s dock at the Albany Basin and post notices that it was scheduled to depart for New York, usually within a day or so. As canal boats arrived at Albany, the captain would tie up at the A&C Line’s dock and hire the A&C Line to transport the canal boat to the city.

Typically, the canal boat could be lashed to as many as thirty other canal boats, in a pack two boats wide, and at the appointed hour the tow to would begin. The Austin, being one of the largest and most powerful tow boats on the Hudson, could tow over 50 boats at one time.

Transporting a large pack of canal boats was a hazardous task. Boats could not stop immediately and crosscurrents sometimes caused them to slide sideways. This made them hard to keep together without side-swiping other boats in the pack or other vessels passing the tow on the river. Storms could also play havoc with large packs of towed boats and barges.

To try to protect themselves from losses, the towboat companies required that the canal boat owners sign an agreement absolving the towboat owners from liability for damages incurred to their boats while being towed.

In 1853, the A&C’s main competitors for towing work on the Hudson River were the Schuyler Line owned by Samuel Schuyler, a black resident of Albany and rumored to be a descendant of the famous Schuyler family, and the Robinson & Betts Line. The Schuyler boats were noted for their red signal lights and red walking beam and Robinson & Betts used white lights and white walking beam.

In April of 1855, Jeremiah Austin, Jr. purchased the passenger steamboat General McDonald and had it converted to a towboat. The General McDonald was 222 feet long and had a 29 foot 7 inch beam with a 68 inch diameter cylinder and 11 foot piston stroke. The General McDonald had originally sailed in Chesapeake Bay and later ran a route between Cape May, New Jersey and Philadelphia.

On March 10, 1856, the A&C Line’s Albany agent, Captain George Monteath died. Albany newspapers described him as having been born in Dumblane, Scotland in 1778 and owning the Albany & Canal Line of Tow Boats where he made a fortune. Monteath may have been a part-owner of the A&C Line, or the newspaper was incorrect and he was just their Albany agent.

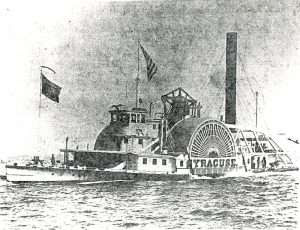

Austin’s third towboat was the Syracuse. The Syracuse was built as a towboat in 1857 and was said to be the most handsome and powerful towboat on the Hudson River. The Syracuse was 218 feet long and 35 feet 8 inches wide with a 72 inch drive cylinder and a 12 foot piston stroke. With the appearance of the Syracuse and a few other large towboats, towed packs of canal boats now sometimes reached close to 100 boats in rows four boats wide. Austin’s A&C Line’s fourth towboat was the Ohio, a passenger steamboat that had started its career running on the Delaware River and more recently carried passengers from Philadelphia.

Austin’s fifth towboat was the Silas O. Pierce, a small side-wheel steamboat built in 1863 by the ship-building company of Morton & Edmonds and immediately chartered to the federal government to be used as a troop transport moving Civil War troops to and from Fortress Monroe, Virginia.

During the war, bags of oats were piled around the Pierce’s pilot house to protect the pilot and crew from Confederate snipers. It was a tactic of Confederate soldiers to hide in woods adjacent to streams and wait for Union transports to come by. They would then try to shoot crew members and capture the ship and cargo.

When Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, was captured at the end of the war, he and his family were transported to Fortress Monroe under heavy guard on the Pierce. The Pierce also patrolled the Potomac River stopping all small craft, searching for John Wilkes Booth following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

At the end of the war, the Pierce towed the barge Catskill to New York Harbor where she ended her service. Austin purchased the Pierce at New York Harbor.

Jerry Austin and his father were active in the Albany business community for more than 50 years. In about 1865, an Albany newspaper ran an article saying “The following citizens of Albany returned an annual income of over $20,000 and upwards,” and then listed 32 residents of Albany.

J.J. Austin was listed fourth with an annual income of $75,848, behind only Erastus Corning ($101,300), Alfred Van Santvoord, owner of the Albany-New York Day Line Steamboats ($85,376), and Robert H. Pruyn, president of National Commercial Bank and an influential attorney ($78,370).

General John F. Rathbone, president of the Rathbone-Sard Stove Casting Company was behind Austin in fifth place at $68,150. Austin’s closest shipping competitor was Samuel Schuyler who was twenty-first on the list at $21,417. Austin was also a director of National Commercial Bank in 1866 and a trustee of Albany Rural Cemetery. The book Old Steamboat Days on the Hudson River by David Lear Buckman, described the life of the canal boat owners and operators as they were being towed down the Hudson:

“Among the most picturesque sights on the Hudson are its floating towns. No more fitting term can be used to designate the long lines of canal boats lashed together four and five abreast and strung out for nearly a half mile, being towed down the river, so slowly that the movement is hardly discernible.

“The tows which are made up at the basin above Albany where the Erie Canal enters the Hudson, look very much like floating towns, presenting the regularity of blocks of buildings, with lanes of open water between, not unlike streets in appearance.

“On one, the captain’s wife may be seen washing clothes just outside her cabin door and on another the entire wash hanging up to dry… Little shirts indicate the presence of children, and if you watch for them you will find them on some of the boats, playing with other children from the other craft in the tow or running over the decks with their dogs at such a rate, one wonders [why] they do not fall overboard. Some of the cabin roofs are fitted up with gay canvas awnings, hammocks and swings. Bright hewed geraniums and other flowers in boxes in front of the cabin windows add to the picture. Sometimes a group of men and women will be seen on one of the boats, spending a pleasant hour eating and listening to the lively music of a concertina or guitar… The mules that towed the boats on the canal were quartered in a stable built in the bow of the boat.”

In 1866, Austin’s A&C Line of Towboats was probably the largest and most successful towboat line on the Hudson River, but that year also signaled the start of a series of unfortunate events.

On the evening of May 15, 1866, the heavily laden freight and passenger steamer Rip Van Winkle departed New York for Troy, just north and across the river form Albany. At 2 am the next morning the Rip Van Winkle passed Rodger’s Island and was approaching Brandow’s Hollow when her pilot observed lights from three tow boats. The three boats were the Joe Johnson and the Syracuse coming down the Hudson and the Arnold going up the river; all had tows. Many of the tows also had their lights on creating a display of lights that appeared to cover the entire width of the river.

The Syracuse moved to the middle of the river and prepared to pass the Joe Johnson, both coming down the river. At the same time the Rip Van Winkle blew a long whistle to signal that she intended to move to her left to pass the Arnold going up the river.

The Rip Van Winkle moved left and prepared to pass the Arnold. As the Rip Van Winkle began to pass the Arnold, the steamer’s pilot testified:

“just before I got abreast of the Arnold … the steamer Syracuse… altered her course… and came right… towards us. I didn’t slow the boat nor did I stop her… I thought I could outrun her when I saw her coming… I hove my wheel over aport… and that took us more to the eastward… Then the Syracuse hit us… It was the barge that she had alongside that hit us… it carried away our deck beams, and side house and water wheel… disabled our engine, and then we drifted, til in time we drifted ashore.”

The large ice barge Colgate, which was being towed by the Syracuse, had collided with the Rip Van Winkle and both were seriously damaged. The Rip Van Winkle brought suit against the A&C Line for damages.

The U.S. Supreme Court found in favor of the Syracuse. The Court said that the towboats were known to have less control over their cargo than the powered steamer Rip Van Winkle and the Van Winkle had been accelerating when the accident occurred while the Syracuse had her engine disengaged, and since the actual impact had occurred to the sides of both ships rather than the front, the court felt that both boats had sheared (drifted sideways toward each other) and the Rip Van Winkle could have avoided the accident because she was under power and had better control, while the Syracuse could not.

On March 13, 1869, Jeremiah Austin’s house at 295 Hamilton Street was broken into at night while Austin was upstairs asleep and about 50 items of silverware were stolen. A second burglary occurred the following night at the home of Belle Lorrimer. The silverware was discovered under a nearby bridge and when Edwin Van Gaasbeck and John Burt returned to take it, they were arrested and subsequently sentenced to 10 years in Clinton State Prison at hard labor.

In December, 1870, the U.S. Supreme Court heard a second liability claim involving the Syracuse. In this case the Syracuse had left the Albany Basin headed for New York Harbor towing 40 boats. One of them, the Eldridge, was a late arrival and was one of the last lashed to the end of the double line of 40 boats. It was stated in testimony that although 40 boats was a large count, it was not a large number for the Syracuse which had towed as many as 52 canal boats at one time. (By then, some tows were actually larger, consisting of 70 or 80 canal boats at one time.)

Within a mile of the Battery in New York Harbor, the Syracuse’s pilot testified that he saw an unusually large number of boats in the harbor but he assumed that the towboat Cayuga had just preceded him through this area safely.

It was well-known that tow boats coming down the Hudson River with the tide would meet an ebb tide (or cross tide) at the East River. As the Syracuse reached the East River, she took on two small steam-tugs to help guide the end of her dual line of canal boats. As they swept around into the East River, the current coming out the East River swept the line of canal boats sideways with the boats at the far end sweeping furthest.

The Eldridge, near the end of the line, was swept out furthest and struck a large ocean-going brig which laid at anchor and which also swept toward them. The Eldridge struck the brig’s stern and the Eldridge sank. The owner of the Eldridge sued for damages.

Testimony showed that there were no unusual circumstances beyond the strong current coming out of the East River which normally had a strong current. The pilot of the Syracuse testified that he could have stopped the tow above Thirteenth Street and divided it into smaller tows but at that point he was unaware of the heavy traffic below him near the Battery.

The U.S. Supreme Court found that even if the canal boat had agreed to be towed at her own risk, the law required the towing boat to exercise reasonable care, caution and maritime skill and if these were neglected and disaster occurred, the towing boat was liable.

The court felt that the Syracuse should have stopped above Thirteenth Street until they could determine that it was safe to bring a large tow into the harbor. By proceeding without adequate knowledge, the Syracuse was liable. The A&C Line was ordered to pay the damages.

This decision probably caused the A&C Line a considerable loss and may have placed them in financial difficulty.

Then, on July 21, 1875, the boiler of Austin’s Silas O. Pierce exploded violently. Two crew members were badly scalded and subsequently died within a few days of the accident.

It was a fourth disaster however, that may have caused A&C’s final demise.

In 1875, an appellate decision was handed down by the New York Supreme Court that found Austin’s A&C Line liable for $7,814.24 in damages caused by the August 19, 1863 collision of the canal boat J.L. Parsons, being towed by the General McDonald, with the Washington, being towed by the Austin. Both towboats, the General McDonald and the Austin were owned by the A&C Line.

The A&C Line had argued that the accident was caused by the fact that the J.L. Parsons did not have her lights on. The J. L. Parsons was sunk and her cargo of corn was lost. The Arctic Insurance Company paid the claim and sued Austin for recovery. The judge felt that since both towboats were owned by Austin, the A&C Line was responsible for the accident.

The A&C Line went into bankruptcy and in the summer of 1876 was placed in the hands of a receiver. At the Receiver’s Auction in 1876, the prize boat of the A&C Line, the Syracuse, was purchased by Samuel Schuyler of the Schuyler Line. The other boats, the Austin, General McDonald, and Silas O. Pierce were bought by the Cornell Line. When the Schuyler Line ceased operations in 1892, the Syracuse also went to Cornell. The Ohio was listed as abandoned in 1878.

After the failure of his towing line, Captain Jeremiah J. Austin, Jr. moved to Stamford, Connecticut. He died there on Sunday, November 29, 1879 at the age of sixty, only three years after his business folded. His burial record at Albany Rural Cemetery indicates that he died of typhoid fever.

On May 23, 1880, the New York Times re-published an article that had appeared in the Albany Argus the day before. The article was entitled: “Ex-Millionaire’s Fifteen Dollar Estate.” The article said that Jeremiah J. Austin Jr., once one of Albany’s wealthiest residents, had died on November 29, 1879. It said that due to Austin’s death, an application was filed with Surrogate Judge Francis H. Woods the previous day and the application for letters of administration on his estate estimated the value of the estate at $15.

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

PLEASE SUBMIT ALL ANSWERS BY 5 P..M.

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

PILES OF ROCKS, RUBBLE AND TRASH IN BACK OF COLER,

THE SITE OF LIGHTHOUSE PARK EXPANSION

GLORIA HERMAN AND THOM HEYER GOT IT RIGHT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Greg Tranter is a prominent, award-winning Buffalo sports historian, curator, and collector. He has written two books, Makers, Moments & Memorabilia: A Chronicle of Buffalo Professional Sports (2019) and RELICS: The History of the Buffalo Bills in Objects and Memorabilia (2021), and numerous articles on Buffalo sports history for publications such as The Buffalo News and Western New York Heritage magazine.

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment