Thursday, March 30, 2023 – AUDUBON TERRACE AND THE HISTORY OF ITS CREATORS

FROM THE ARCHIVES

THURSDAY, MARCH 30, 2023

ISSUE 952

Archer M. Huntington:

Titan Arts Patron of New York City

***********************

“DOLLARS FOR DAFFODILS”

UPDATE:

OUR FIRST DONATIONS HAVE ARRIVED

THANK YOU TO RACHEL MAINES AND GLORIA, MARK HERMAN, CAROLINE CAVALLI, MR. & MRS. RICHARD MEYER, NANCY BROWN, ARLENE &STEVE BESSENOFF, MARIE EWALD & DAVID DANZIG, BARRY & JUDY SCHNEIDER, & MICHELLE ROY, ARON EISENPRESIS & ANNONYMOUS FOR THEIR DONATIONS.

WE ARE WAITING TO ADD YOUR NAME TO OUR DONOR LIST

We need your help this spring to help us restore and enhance our garden.

Our goal is $2000.00 for a complete restoration of soil, drainage, plantings and fencing.

We will update donations daily. We will list our donors.

Join us in making our garden thrive again.

ALL DONATIONS ARE TAX DEDUCTIBLE

TO MAKE YOUR DONATION: https://rihs.us/donation/

TO MAKE YOUR DONATION BY CHECK: R.I.H.S., 531 MAIN STREET, #1704. NY NY 10044

Archer M. Huntington: Titan Arts Patron of New York City

March 27, 2023 by Andrew Kurt

As New York City reached its Silver Jubilee in 1923, one of the ways it celebrated 25 years since its formation as a greater city uniting the five boroughs was to have residents vote on the six people who had done the city the most good. Who made the Big Apple’s early honor list?

Might you have guessed Millicent Hearst, wife of the famous press baron? Nathan Straus, co-owner of Macy’s and Abraham & Straus department stores and renowned philanthropist? Another one of those recognized as a civic hero was the magnificent patron Archer Milton Huntington. Ever heard of him? Although his and other names in this select circle might not be household figures today, this towering figure of a century ago left a mark worth remembering.

Huntington (1870-1955) utilized the enormous fortune inherited from his father, railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington, to found or assist nearly two dozen institutions. With a vision, drive, and acquired knowledge far surpassing other patrons of the arts in the Gilded Age and beyond, in 1908 he established the museum of the Hispanic Society of America, of which the New York Times apperceived “there is nothing narrow or haphazard about its origin and purpose.”

Perched on the Audubon Terrace at Broadway and 155th Street when Manhattan was seeing expansion northward, it was joined with Huntington’s patronage by the American Numismatic Society, The American Geographical Society, and in 1922 and 1923, respectively, The Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation and the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

For several years he was president of the first two of these societies. An Atlas of public learning, he would hoist numerous other institutions, some in the city and some elsewhere including in Spain, where he heavily endowed the Casa de Cervantes and the Casa del Greco.

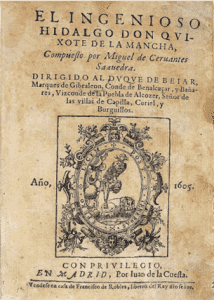

First and foremost a library, the HSA made the richness of Spain and the Hispanic world available for study with thousands of manuscripts and early printed works – first editions of works by Cervantes and Lope de Vega, to name but two notables, not to mention other earliest printings from Mexico and elsewhere in Spanish America – in addition to facsimiles, reprints, and a vast array of modern studies.

Such an institution raised the scholarly access at a time when interest in Spain was just being kindled and foresaw the “closer approach between the North and South American peoples,” as the New York Times observed in a review at its opening. It’s still doing all that.

By 1923 the HSA had on display paintings by Old Masters in Spain, among them Diego Velázquez’s compelling “Portrait of a Little Girl” (ca. 1640) and Antonio Moro’s (or Antonis Mor’s) magisterial “Duke of Alba” (1549); maps including Juan (Giovanni) Vespucci’s worldmap of 1526; a precious collection of Hispano-Muslim ceramics, lusterware, silks, rugs, and carved boxes; and ancient through early modern sculpture, wares, and coinage.

The enterprising Huntington had even installed revolvable capsules that permitted the viewer to see both sides of the coins in their cases, normally not possible. Ingenuity in physical arrangement and lighting marked Huntington’s sense of maximizing space and creating an effective experience.

To gather his bountiful yield he had literally got into the dirt as well as working his way into the right social circles in Spain and judiciously putting book and art dealers into action. Specifically appointing women as curators and librarians, he stood apart from philanthropists of his day such as his cousin Henry E. Huntington of the famous library and art museum in California founded in 1919. Henry was actually emulating his younger relative in that enterprise, overcoming an earlier disdain for museum patronage.

A special exhibition in 1909 that quickly helped put the Hispanic Society in the spotlight was that of Joaquín Sorolla, a master of plein air impressionism whom Archer Huntington came upon while seeking out art in London. It could equally be said that Huntington put a new spotlight on Sorolla, until then hardly known in America.

On view for just a month, the exhibition drew close to 160,000 visitors, then a New York record. Bursting demand pushed closing hours to 11 pm. Soon Huntington commissioned Sorolla’s 12-foot tall murals labeled “Provinces of Spain” (1913-1919), also known as Vision of Spain, unfolding some 230 feet across the walls of the western wing and adding to the museum an astounding element when opened to the public in the mid-1920s.

Special exhibitions up to that time included one in 1911 of the De Forest Collection of Mexican pottery and another six years later of the famous tapestries and carpets from El Pardo Palace (Madrid), among whose eighteenth-century wall weavings from the Royal Manufactory were ten made from cartoons drawn up by Francisco de Goya. Never before had these items been removed from El Pardo.

South American historians above all must have been impressed two years later with a showing of two thousand original documents from Lima spanning from conquistadors to Peru’s wars of independence in the early nineteenth century, from the collection of Peruvian senator and antiquarian Jorge M. Corbacho.

Archer Huntington’s museums alone, even just the HSA, would merit recognition on the Silver Jubilee of New York City. But his contributions went much further. Already at twenty-seven years of age he had produced an outstanding three-volume manuscript printing – translation – notes of El Poema del Cid from the unique manuscript, in Madrid – quite a feat for a young man without formal education, instead relying on a singular focus and a preparation afforded by his means.

Honorary degrees were conferred on him by no less than Yale University (1897), Harvard University (1904), Columbia University (1907, 1908), University of Madrid (1920), and Kenyon College (1921). He was elevated to Spain’s major Orders: Isabel la Católica, Alfonso X, Alfonso XII, Carlos III, Plus Ultra. In 1916 he was made member of the Orden del Libertador of Venezuela.

By the early 1920s the Hispanic Society’s publications of specialized study were advancing research on Spain, Portugal, and the vast territories held by Spain. The library had grown to tens of thousands of items. A massive coin collection, although not publicized and only a portion of which was displayed, condensed several eras of the Iberian Peninsula in one location in New York. Later in life Huntington personally delivered it in crate after crate on indefinite loan to the American Numismatic Society next door. Who knew, for instance, that the largest collection of gold coins from the Visigothic Kingdom in Spain and southwestern France (around 450-711) are nestled in New York because of his doing?

New York City would headquarter the hugely ambitious millionth scale map of Hispanic America, which The American Geographical Society began in 1920. Twenty-five years later this essential groundwork for comprehensive geographical studies of Hispanic America was completed. Huntington’s generosity made the giant project possible. His opening outlay of $25,000 eventually accrued to a quarter million dollars – roughly 8 million in today’s terms.

Financing of a lengthy study of the native peoples of the Southwest by The American Museum of Natural History, New York led to numerous publications and a new landmark. Discovery of a 12th/13th -century Pueblo Great House near the New Mexico town of Aztec, donated by the museum to the US Government in Huntington’s name, gave rise to Aztec Ruin National Monument established by presidential proclamation in 1923.

1923 happened also to be the year that Huntington married the already acclaimed sculptress Anna Hyatt. She went on to grace not only the Audubon Terrace but many other venues with her creative genius. In subsequent years Archer Huntington added more personal accomplishments and the HSA made estimable acquisitions, as it has continued to do to the present.

Huntington’s chef-d’oeuvre, now the Hispanic Society Museum and Library, an “uptown outpost” sitting today “in the Arctic Circle of New York’s Cultural Globe,” might not draw the crowds it once did, but it never ceases to amaze visitors. Monetary wealth brought artistic and literary wealth across the seas in great measure.

Huntington would add the Medal of Merit of the Saint Nicholas Society of New York City (1939) to his host of recognition, although he shunned the limelight and frequently donated anonymously. The Gari Melchers Gold Medal of the Artists’ Fellowship, Inc., given annually “to a person or an organization that has materially furthered the interest of the profession of the fine arts,” was awarded to him five years after its inception at the end of World War II.

When Huntington died in 1955 plaudits sounded around the world. But already in his early life he had left a mark, helping solidify New York’s still emerging place as a beacon of culture and learning. On the Silver Jubilee he was given a flag of the city for his selection. It is fitting for us to remember the popular recognition a century ago of this titan New Yorker. By chance, after some years of fundraising and renovation have kept the Hispanic Society Museum and Library closed recently, it will partially reopen in Spring 2023, more than ever one of New York’s precious gems. It will be quite an anniversary gift.

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

PLEASE REPLY BEFORE 4 P.M.

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

THE FORMER GENERAL THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY

A portion of architect Charles Haight’s mid-1800s masterpiece and Federal Historic Landmark, the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, have been transformed into The High Line Hotel.

JOYCE GOLD AND ELLEN JACOBY GOT IT RIGHT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: Archer Milton Huntington (second from left), in Spain in 1892 traversing the route of El Cid, from Burgos to Valencia; Main Hall of Hispanic Society Museum & Library (Mark B. Schlemmer, CC); Miguel de Cervantes, El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha, 1605, (Hispanic Society Museum and Library); Duke of Alba (Fernando Álvaro de Toledo, Third Duke of Alba), 1549, oil on canvas by Antonio Moro (Hispanic Society Museum and Library); and Portrait of a Little Girl, ca. 1638-42 by Diego Velázquez (Hispanic Society Museum and Library).

PHOTOS COURTESY OF JUDITH BERDY

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment