Monday, April 10, 2023 – The Tompkins Square area has always had interesting activities

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, APRIL 10, 2023

ISSUE 960

Justus Schwab & East Village Radicalism

NEW YORKALMANACK

Jaap Harskamp

Justus Schwab & East Village Radicalism

April 9, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp

Today, the city of Frankfurt-am-Main is the largest financial hub in Continental Europe, home to the European Central Bank (ECB), the Deutsche Bundesbank and the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. The same city was at one time the epicenter of a liberal uprising that swept the German states. The Frankfurt Parliament was convened in May 1848; its members were elected by direct (male) suffrage, representing the full political spectrum. In the end, the revolution of 1848 failed and was suppressed with excessive force and retribution.

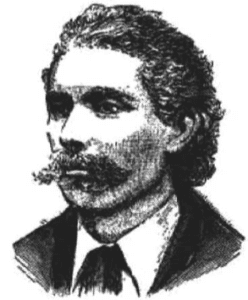

Many of those who had taken part in the uprising, collectively known as Forty-Eighters, moved to the United States (some of the refugees would fight on behalf of the United States in the Civil War). Others were arrested and some rebels served long jail sentences. One of them was a person by the name of Schwab (a Jewish regional name for a native from Schwaben [Swabia]) who ran a tavern in Frankfurt. Just after the birth of his son Justus, he was convicted to four years imprisonment for rioting against the Prussian military.

Trained as a mason, young Schwab became active in the German labor movement in the late 1860s. Conscripted into the army, Justus deserted and fled to France. He migrated to New York in May 1869, settled in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, and opened a small saloon named Liberty Hall that would become a hotbed of anarchism and social radicalism.

Allons Enfants on Tompkins Square

Schwab started his working life in New York in the building profession, but following the Financial Panic of 1873 (in which at least a hundred banks failed) he lost his job and became one of an ever-increasing number of unemployed laborers.

He joined the German Workingmen’s Association in their demand that the city provide aid to those affected by the depression. Rejecting offers of charity, labor movements demanded social protection programs that would create jobs for the masses desperately seeking work. An era of labor agitation followed to which the authorities took a heavy-handed approach.

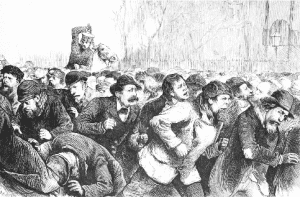

In January 1874 a protest meeting of an estimated 10,000 workers, including 1,200 members of the German Workingmen’s Association, was called in Tompkins Square Park, East Village. Without the organizers’ knowledge, their permit to assemble in the park had been revoked. A force of 1,600 policemen crushed the demonstration by brutally dispersing the crowd.

When Schwab and fellow workers resisted, they were clubbed by the cops. The square was cleared, but Schwab – a powerful, red-haired and bearded man known to friends as the “Viking” – marched back whilst holding a Paris Commune’s red flag and singing “The Marseillaise.” He was arrested and charged with incitement.

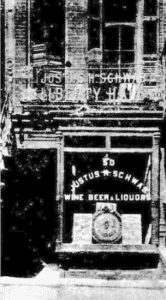

Justus married shortly after the incident and opened a saloon at 50 East First Street in the East Village neighborhood of Manhattan. Seen as a potential rabble-rouser, the police kept him under surveillance. Unwilling to pay bribes or give officers special treatment, his saloon was frequently raided.

He was also targeted by the temperance movement who celebrated his arrest in June 1876 for selling beer on a Sunday. Once acquitted, he became determined to take on the authorities by turning his establishment into a center for radical thinkers and activists.

On occasion, Schwab advertised his subculture saloon as “Pechvogel’s Hauptquartier” (losers’ headquarters) deliberately evoking an image of the bohemian outcast and beer-drinking anarchist mocked by New York’s mainstream society. The same ploy would be used over and again by urban protest groups during the 1960s.

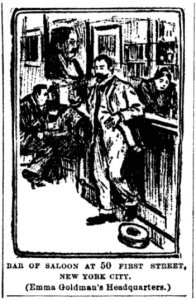

Inside the Saloon

Small in size, the saloon was described as a bier-höhle (beer cave: a pun on “bierhalle”). The tavern developed into a multi-national meeting place for political refugees and their American sympathizers, including the authors John Swinton and Ambrose Bierce as well as Sadakichi Hartmann, the Japanese-American poet and art critic. The bar was decorated with a bust of Shakespeare and several prints depicting the French Revolution.

Vanguard authors and artists intended at the time to transform art by fusing politics and painting, advocacy and poetry. They claimed that modernism should be the aesthetic realization of anarchist ideas. Creativity was an act of rebellion. Renewal implied destruction. The French avant-garde had suggested that the verb “trouver” (to find) is etymologically linked to the Latin “turbare” (to disturb; cause turbulence). Artist and activist happily shared the same saloon.

In a rich German-American tradition, Justus Schwab was a music lover and talented singer (a man blessed with a “golden voice”). He was leader and member of the Internationale Arbeiter-Liedertafel, a German anarchist choral society founded in 1884. Music was also an essential part of his saloon’s ambience. At the back of the establishment, placed on a platform, stood an old and smoke-stained piano. When requested, the landlord himself would happily play “The Marseillaise” or belt out “The Internationale” and invite his clientele to partake in a spontaneous concert of protest songs.

More ‘serious’ anarchists condemned such convivial gatherings as a waste of valuable time. They demanded (immediate) action, not recreational activities. They rejected joviality as an expression of a petty club mentality that was detrimental to the movement’s credibility. Rebel and dreamer Schwab would have laughed at these arguments. Fundamental to his political outlook was the idea that the fight for liberation must be an assertion of joy and fortitude.

His saloon was much more than a taproom or artist’s den. It developed into a proper infoshop, a term coined in anarchist circles to denote a center that served as a node for the distribution of information and resources to local comrades. The tavern functioned as a library by stocking books, pamphlets and an array of newspapers.

Schwab’s collection consisted of some six hundred books. His back room was used as a meeting place and reading room for socialists and anarchists. Amongst his visitors was Lithuanian-born Jewish immigrant Emma Goldman. She would make ample use of Schwab’s generous lending policy. To her, his saloon represented a political education and a space of freedom. For a while, it was also her mailing address.

Anarchist Nomad

Schwab was an active participant in political discussions and a member of the Socialist Labour Party (SLP). As it was the case in Europe, the history of radical socialism in the United States was one of conflict and infighting. The road to utopia is covered with potholes.

Disagreements about the reformist direction of the SLP would lead to the expulsion of Schwab’s faction from the Party. In November 1880 its members formed a new grouping by the name of the Social-Revolutionary Club which met weekly at Schwab’s saloon. Its increasingly anarchistic orientation was influenced by the arrival of Johann Most. The latter’s life reflects in many ways that of other European anarchists who, because of persecution, were forced into a nomadic existence. It explains the movement’s restless spirit. Many of its members were or had been continuously on the run from the authorities.

The illegitimate son of a clerk and governess, Johann Most was born in Augsburg, Bavaria, in February 1846. His mother died young and he was brought up by a stepmother who maltreated him. Working as a journeyman bookbinder, he plied his trade from job to job, working in fifty cities in six countries from 1863 to 1868. He moved to Vienna in 1867 where he joined the International Working Men’s Association (the First International). A committed socialist he became a well-known and – to the local authorities – an unwelcome street orator. In 1871 he was deported from the country.

Having returned to Germany, he worked as a journalist for the Berliner Freie Presse. In 1874 he was elected as a Social Democratic deputy in the Reichstag, but after the passing of Bismarck’s anti-socialist laws he was forced to flee the country.

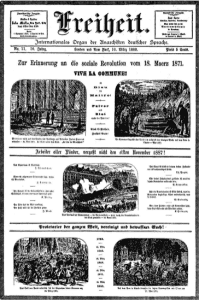

Johann Most arrived in London in 1878. The following year he began publishing the German-language newspaper Freiheit (Freedom) from an office in Titchfield Street, Westminster, targeting the international community of expatriate Germans and Austrians. The notorious slogan of “propaganda of [by] the deed” which came in circulation during that period is associated with his thinking and activities.

When Most published an article in 1881 justifying the assassination in Russia of Tsar Alexander II, he was arrested and sent to prison. Released in 1882, he moved to the United States and settled in Chicago where he continued to publish his newspaper.

Webster Hall

Schwab had been a subscriber to Freiheit since 1880 and the newspaper’s activist stance radicalized his own thinking. In 1882 he became interim editor of the paper whilst Most was making his way from Europe to the USA. The two remained closely associated for a number of years, with Schwab formally introducing Most to the Social-Revolutionary Club at his first appearance before an American audience.

However in 1886 the two fell out over a scam played out by some anarchists who first insured their tenements and then set fire to them. Several fire-raisers were imprisoned. The negative publicity caused a split in the German movement. Whilst Most refused to denounce the swindle, Schwab warned fellow radicals that the means of action must never desecrate the end. Most and friends stopped frequenting Schwab’s premises.

Justus contracted tuberculosis in the winter of 1895 and was bed-ridden until his death in December 1900. His funeral was attended by representatives of the various opposing factions in the movement of German-American anarchism, their differences forgotten in sorrow. A tearful Johann Most was also present at the occasion. According to The New York Times, the procession comprised nearly 2,000 people. Rarely has the death of an anarchist caused such a collective outpouring of grief.

Schwab’s saloon set the scene for later developments in the Village. Webster Hall was built in 1886 on East 11th Street. Commissioned by cigar maker Charles Goldstein and designed by Charles Rentz, the building was operated from its inception as a “hall for hire” and used for such social occasions as balls, receptions or Hebrew weddings. It soon became better known for its radical political gatherings, particularly after 1900 when the anti-establishment politics of the so-called Greenwich Village Left were widely communicated.

Webster Hall was turned into a presentation stage for controversial political factions and rebellious artistic groups. It was from here that Emma Goldman began to stir the national political sphere. In rousing speeches she developed provocative ideas that originated from the time that she had been a regular at Schwab’s establishment. It all had started in a Village beer cave in East First Street ran by a German-born host with a passion for French revolutionary songs.

ABOVE: ROSINA ABRAMSON, FIRST RIOC PRESIDENT AND FROM 2008-2010 VICE PRESIDENT OF RIOC. SHE RAN AN EFFICIENT OFFICE WITH CONSTANT COMMUNICATION AND OCCASIONAL INTERESTING INTERACTIONS WITH THE COMMUNITY. WE NEVER DOUBTED HER INTEREST IN THE RESIDENTS AND MAKING THE ISLAND A BETTER PLACE TO LIVE.

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Illustrations, from above: Portrait of Justus Schwab published in Leslie’s Weekly (New York) in February 21, 1874; Mounted police attack on demonstrators, Tompkins Square Park, 1874; Schwab’s Liberty Hall saloon at 50 East First Street; Schwab’s saloon according to Laporte Weekly (Pennsylvania), October 24, 1901; and Title page of Freiheit, March 10, 1888.

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment