Monday, May 8, 2023 – BEFORE MAE WEST***VICE WAS NOT ACCEPTED***

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, MAY 8, 2023

ISSUE 984

Vulgarity & Vice:

Times Square in the 1920s

JAAP HARSKAMP

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Vulgarity & Vice: Times Square in the 1920s

May 7, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp Leave a Comment

The 1920s was a decade of change and upheaval. While Europe was recovering from the First World War, the United States saw a period of economic growth and prosperity in which the country’s focus shifted from rural areas to the cities. It was also a time of great creativity in art and entertainment. New York City set the pace.

The focus of excitement was the theater with an unprecedented public demand for plays and performances. The era saw a burst of theatrical construction with more than thirty new venues appearing in the city. These were Broadway’s prime years. During the 1927/8 season, over 260 productions debuted there.

Times Square’s accessibility began to flourish during the 1920s when all forms of public transportation stopped at 42nd Street. Compared to other major crosstown thoroughfares, the street was developed relatively late. The first theater opened its doors in 1899 and was followed by a range of other entertainment venues alongside the development of top-end office space around Grand Central Terminal.

With the building boom taking place, the call for advertising space around Times Square increased sharply. During the night the district became covered in a sea of light, producing a huge splash of color. The dazzling illuminations were a public attraction in their own right. Leisure became a booming business. Broadway offered its audiences a rich choice of plays, musical comedies, revues, operettas and other forms of fun and entertainment. A key player in these developments was a Jewish immigrant from Hungary.

The Woods Factor

Albert Herman Woods was born Aladore Herman in January 1870 in Budapest, but his family moved to the city of New York when he was a child. Growing up in the immigrant district of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, he would roam the streets and skip school. Away from the gloomy tenements of his youth, he was lured by the gleaming lights of the theater.

Woods would become one of New York’s most prolific theatrical producers, staging over 140 plays on Broadway including a number of blockbusters. Having been involved in managing tour companies of popular melodrama at the start of his career, he soon turned his attention to Time Square.

In August 1903 he opened his first show with Theodore Kremer’s melodrama The Evil Men Do at the American Theatre in West 42nd Street (built in 1893; closed in 1930 and demolished two years later). Sensing that melodrama was losing its appeal, Woods was attracted towards an alternative genre that had previously taken Paris by storm.

Georges Feydeau was a wildly popular French playwright of the so-called “Belle Époque.” He is remembered for plays that delighted audiences from the 1890s to the pre-World War I era. His farces were marked by closely observed characters with whom his (urban) audiences could identify.

The dramatist created a new type of comedy consisting of slamming doors, mistaken identity, hidden onlookers, ridiculous dialogue, sexual innuendo, adultery and improbable plots that, once it had reached London and New York City, became known as the “bedroom farce.” Woods introduced the genre to Broadway.

Loved by the public at large, the emerging American passion for farce was closely scrutinized by anxious local authorities and angry morality crusaders. One of the attractions of the plays produced by Woods and his collaborators was pushing the boundaries of propriety and correctness beyond accepted norms. He encountered and almost encouraged legal intervention – it all added to publicity and promoted a scramble for tickets.

Let the Good Times Roll

Paul Meredith Potter, a playwright and journalist for the New York Herald, established a reputation for having turned George du Maurier’s best-selling novel Trilby – set in bohemian Paris – into a stage play in 1895. Woods took note of his success.

Having read the original version of the play Loute (1902) by the prolific Parisian farceur Pierre Vebler, he was quick to purchase its production rights. Woods commissioned Potter to adapt the play, the plot of which portrays several couples in a tangle of adulterous affairs.

Prior to opening at Weber’s Theatre on Broadway in February 1909, preview performances of The Girl from Rector’s were scheduled in Trenton, New Jersey. The opening matinee left some of the audience in shock. A group of local clergymen issued an official complaint about the play’s immoral contents upon which the police banned any further staging. The fall-out over the farce almost guaranteed its success. Once at Broadway, the show ran for 184 performances until July 1909.

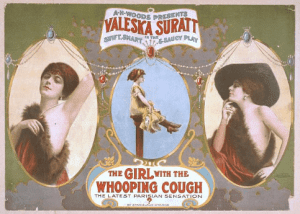

Encouraged by public interest in the genre, Woods started preparation for the next salacious bedroom farce. In April 1910, he produced The Girl with the Whooping Cough, an adaptation by Stanislaus Stange of a French play. The story follows the misbehaviors of Regina as she passes whooping cough to numerous lovers. The leading role was played by Valeska Suratt, a young vaudeville actress who was billed as “The Biggest Drawing Card in New York.”

The City’s 94th Mayor William Jay Gaynor was not amused. He attacked the play as obscene and demanded its immediate closure because of sexually suggestive themes. The Police Commissioner threatened the management of the house that if the play was not taken off the repertoire, he would refuse to renew the theater’s operating license.

Woods got an injunction from the New York Supreme Court that prevented the authorities from interfering with the show, but it did not compel them to renew his license. Left without a home for his show, Woods admitted defeat and was forced to shut it down. In response he built his own venue on 42nd Street. The Eltinge Theatre was named after one of his star performers.

Julian Eltinge (real name: William Julian Dalton) had started his acting career at a young age in Boston. Vaudeville authors at the time introduced cross dressing in their acts to create exaggerated sexual stereotypes. In doing so, they broke the (theatrical) norms of the time.

Julian would become the most celebrated of female impersonators. Simply known as “Eltinge,” his skillful performances turned him into a star. In 1906 he made his London debut at the Palace Theatre on Shaftesbury Avenue to such acclaim that he was invited to give a performance at Windsor Castle in front of King Edward VII (who presented the actor with a white bulldog).

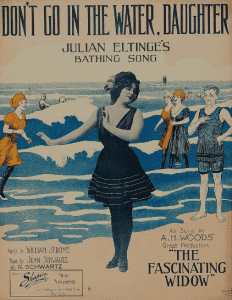

In 1911 Eltinge featured in The Fascinating Widow at the Liberty Theatre, West 42nd Street. A year to the day that the play was first staged, Woods opened his Eltinge Theatre. At the time of the occasion, Julian was America’s highest paid actor and he went on to appear in a string of musical comedies on Broadway (including The Crinoline Girl and Cousin Lucy) written to showcase his skills, although he never performed in the playhouse that carried his name.

The Demi-Virgin

The theatrical empire Woods built was at its peak in the 1920s, producing a series of hit plays that drew large audiences to Time Square.

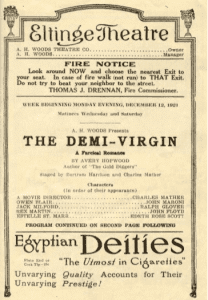

Dramatist Avery Hopwood made his debut in 1906 when his play Clothes (1906) was produced on Broadway. Specializing in risqué comedies, he became known as “The Playboy Playwright.” His 1921 three-act bedroom farce The Demi-Virgin was inspired by an earlier and popular theatrical adaptation of Marcel Prévost’s 1894 novel Les Demi-Vierges. Woods brought Hopwood’s play to Broadway.

Prior to its debut, several preview performances were staged outside New York City, beginning a one-week run in Pittsburgh in September 1921. The play was closed by the city’s Director of Public Safety who objected to its “vulgar” dialogue. Woods gained valuable free publicity from coverage of the closure. The play eventually opened at Time Square Theatre on October 18, 1921, before being transferred to the Eltinge Theatre three weeks later.

Contemporary reviews were negative. Critics condemned the play as immoral due to its sexual situations, revealing clothes and suggestive dialogue. The farce featured a strip poker scene (a game of cards called “Stripping Cupid”). The script also alluded to a sensational rape and murder case that was unraveling in court at the time and involved the silent movie star Roscoe Conkling “Fatty” Arbuckle.

On November 3, 1921, Woods and Hopwood were summoned to the chambers of William McAdoo, New York City’s Chief Magistrate, who had received a number of complaints about the play. The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and the Committee of Fourteen (fighting prostitution in the city) were prominent voices amongst those who opposed the show.

As Woods flatly refused to address any of the objections, McAdoo ruled that the play was obscene, describing it as “coarsely indecent, flagrantly and suggestively immoral.” The producer was accused of violating section 1140a of the New York State Penal Law which prohibited involvement in “any obscene, indecent, immoral or impure drama, play, exhibition, show or entertainment.” Having gathered on December 23, 1921, the Grand Jury dismissed the case that same day. An attempt to revoke the theater’s license also failed.

News coverage of legal actions provided ample publicity. It was reported that lengthy queues for tickets stretched outside the Eltinge Theatre after the case had opened in the magistrates’ court. Once triumphant, the production team milked the controversy to boost ticket sales (so much so, that irritated editors of The New York Times barred Woods name from any notices placed in its pages).

After the Broadway production ended on June 3, 1922, it had been one of the most successful plays of the season, having sold over 200,000 tickets across 268 performances. Woods then launched four road companies to present the play in other cities. The tour continued through 1923 with productions in cities such as Albany, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Washington.

Bust

Woods lost most of his fortune in the early 1930s and never recovered from the blow. Julian Eltinge’s career came to an end as a crackdown on homosexuality and cross-dressing prevented him from performing in costume.

The legal battle over The Demi-Virgin had reopened the discussion about strengthening the role of the censor. The call for new anti-obscenity legislation could be heard loud and clear. The economic slump of the 1930s encouraged those who were concerned about loose or lost moral values to tighten their grip and preach (and enforce) a return to more rigid standards.

Broadway’s building boom that took place in the 1920s was reversed during the Great Depression. Restaurants and theaters in Time Square were replaced by cheap eats and coarse entertainment venues. The turn-down was epitomized by the tumbling reputation of the Eltinge Theatre. It was degraded to an infamous burlesque house that, in the end, was shut down during a “public morality” campaign in 1943.

During the dark days of depression, the lights dimmed and the music died in the entertainment district. Theaters closed in rapid succession, some were demolished and others converted to cinemas. Residents who were accustomed to the “good times” of the 1920s were forced to move from the area and find more affordable properties. It would take some seven decades for Times Square to restore its reputation.

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR SUBMISSION TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHSTORY@GMAIL.COM

|

WEEKEND PHOTO

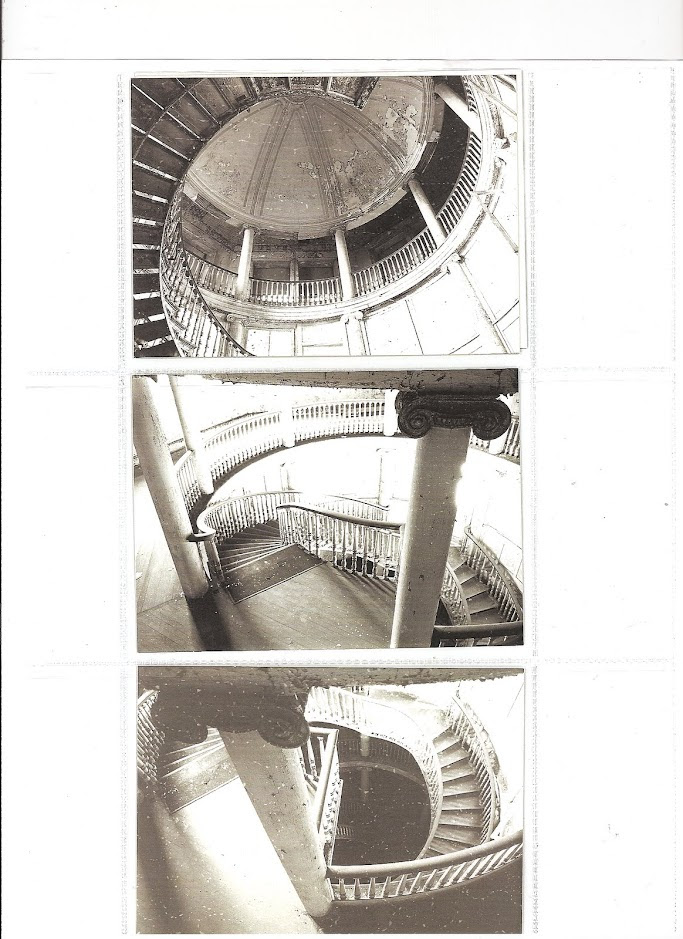

VIEWS OF THE ORIGINAL OCTAGON DOME

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: The Girl with the Whooping Cough; colored postcard of Julian Eltinge, ca. 1907 (Wellcome Collection); sheet music cover for a song from The Fascinating Widow, 1911 (Public domain); and inside page from the December 12, 1921, program for The Demi-Virgin.

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment