Friday, May 26, 2023 – CELEBRATING 1000 ISSUES THIS WEEKEND

FROM THE ARCHIVES

Friday, MAY 26, 2023

Raines Law, Loopholes and Prohibition

by Jaap Harskamp

NEW YORK ALMANACK

ISSUE 999*

Raines Law, Loopholes and Prohibition

May 25, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp Leave a Comment

A loophole is an ambiguity or inadequacy in a legal text or a set of rules that people identify and use to avoid adhering to it. Exploiting loopholes in tax legislation by big corporations or wealthy individuals is a preoccupation of our time. The authorities fight a losing battle trying to plug them as lawyers specialize in finding new and profitable flaws.

The word itself has an intriguing history. Originally it referred to a vertical slit-opening in the walls of a castle from which archers fired arrows at an enemy without fear of being hit themselves. Its etymology was most likely derived from the Middle Dutch word lupen, “to watch or peer.”

By the mid-seventeenth century the term had acquired its figurative sense as a “means of escape.” It then became applied to legal issues, allowing practitioners to identify ambiguities in the law that could be applied to court matters. Over time, the word came to signify the legal “holes” that were there to be exploited and taken advantage of.

A New York liquor tax law was framed by Senator John Raines and adopted in the State Legislature in March 1896. Better known as Raines Law, it was a precursor to Prohibition and took effect in April that year. The law provided one of the more spectacular loopholes in New York’s legislative history.

Blue Laws

America has a long-standing problem with and an ambivalent attitude towards alcohol. When Peter Stuyvesant arrived in New Netherland to take on the role of Director-General on behalf of the Dutch West India Company, he was instructed to impose order in the remote and unruly colony. He immediately issued an edict limiting the sale of alcohol and enforcing strict penalties for violent and/or drunken conduct.

George Washington on the other hand established in 1797 the nation’s largest whiskey distillery in Mount Vernon (producing 11,000 gallons by 1799); Thomas Jefferson brewed his own beer; and in 1833, preceding his career as a legislator, Abraham Lincoln held a liquor license and operated a tavern in New Salem, Illinois.

With the advance of urbanization and industrialization, drinking was increasingly seen as a social problem that needed ‘solving.’ In the first half of the nineteenth century, temperance societies were founded in a number of European countries: Sweden (1819); Germany (1830); England (1831); and the Netherlands (1842). Referring to pathological changes in the body due to sustained intoxication, Swedish physician Magnus Huss coined the term “alcoholism” in 1849.

America’s temperance movement began in the mid-1820s as part of a fervent Protestant revival referred to as the Second Great Awakening (the first Evangelical Revival had swept the colonies in 1730/40s). It gave rise to the nation’s oldest political third-party in existence, the Prohibition Party.

Founded in 1869, members campaigned for legislation to prohibit the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors. Rural and small-town voters affiliated with Evangelical churches provided most of the party’s support. Enormous energy was dedicated to eliminating perceived sin from society (gambling, drinking, prostitution or sloth) through the introduction and enforcement of “blue laws.”

After the American Civil War and following the massive increase of immigration from Europe, beer replaced whiskey as the working men’s preferred beverage. It was the favored drink of the German and Irish newcomers; in temperance circles the craving for beer signified disorderly taverns and dissipation (there was a “hidden” xenophobic element in the push for Prohibition). The moral mission of prohibitionists was the abolition of the saloon.

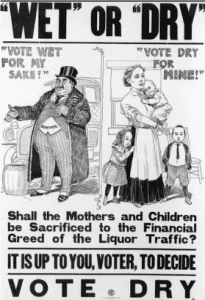

By the mid-1890s New York City counted some 8,000 saloons. Crime and prostitution were rampant in many of these establishments. Saloons were prohibited from opening on the Sabbath, but the police turned a blind eye. As laborers worked six days a week, this single day was their only boozing time. Saloons were financially depended on Sunday clients.

In the meantime, the temperance movement was bearing down hard on New York City’s drinking habits. Moral crusaders and groups like the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) led by the forceful attorney Wayne Wheeler lobbied city leaders to curb the manufacture and sale of liquor. Advocates of an official ban argued that alcohol posed a threat to public decency and moral safety. They successfully campaigned for legal intervention by the authorities.

Raines Law

In 1896 a new law, authored by the Republican Senator John Raines, was passed by the New York State legislature. Nominally a liquor tax, its real purpose was to tackle the “scandal” of intoxication and public drunkenness.

The “Raines Law” put strict limits on the opening of new saloons and made the issue of licenses to sell liquor prohibitively expensive. A renewed crack down on Sunday drinking was the most contested aspect of the regulations. The law exempted establishments that offered the hospitality of ten or more bedrooms, allowing wealthy clients to dine on the Sabbath in hotel-restaurants and order drinks at an open bar with little risk of prosecution.

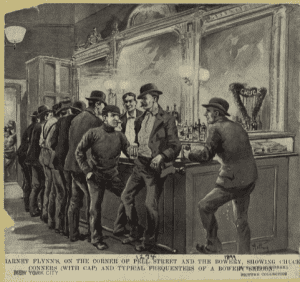

In 1895, young Theodore Roosevelt had been appointed New York City’s Police Commissioner with the specific task of removing corruption and bribery from the force. Ambitious to clean up the city as a whole, he championed the Raines Law and predicted that the measure would solve “whatever remained of the problem of Sunday closing.”

It was huge miscalculation. Saloon owners quickly started to exploit a loophole in the law. They partitioned back rooms and turned upper floors of their bars into “bedrooms” which were rented out to prostitutes or unmarried couples to meet the high cost of licensing fees. By the early 1900s, more than 1,000 Raines Law hotels were established. Sunday drinking continued unabated.

As concerns grew that these “hotels” were operated for sexual encounters and commercial prostitution, the city’s authorities decided on a “men only” policy by forbidding women to enter the premises. One consequence of this rule was that a number of Raines Law hotels developed into relatively “safe” spots for gay men.

Raines Sandwich

Eugene O’Neill, the first American playwright to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, completed his play The Iceman Cometh in 1939 (although he delayed its production until after the war). The play covers two days in the life of a group of “lost souls” who, hiding behind alcoholic pipe dreams, shield themselves from the harsh realities of modern-day urban life.

The action takes place in a Raines Law hotel owned by Harry Hope which is located on the ground floor of a tenement building in downtown Manhattan. In the saloon cheap whiskey is served accompanied by a “property” sandwich described as an old “desiccated ruin of dust-laden bread and mummified ham or cheese.” The reference to a property sandwich, once clear to members of the audience, now needs clarification.

In April 1896, The New York Times published an analysis of the Raines Law in which the author pointed out that any hotel guest could buy a Sunday drink as long as a meal was ordered first. The procuring of drinks was made subordinate to a formal request for food. Another loophole was found. The Raines legislation focused on ordering food, but did not require its consumption.

As a consequence of the necessity to supply a meal before serving drinks, Raines Laws hotels designed a system of preparing fake food to comply with the letter of the law. Saloons produced the cheapest possible sandwiches. The so-called Raines sandwiches were not meant for consumption at all; they were used and re-used. The same disgusting plate could be served multiple times. Some barkeepers decided to present a sandwich made of rubber instead.

Journalist and photographer Jacob Riis fought out his “battle with the slums” in the pages of The Atlantic. In the issue of August 1899 he focused on families that lived in overcrowded tenements. In an article on “The Tenant,” the author describes the life of a laborer who drinks his beer in a Raines Law hotel, “where brick sandwiches, consisting of two pieces of bread with a brick between, are set out on the counter.”

When a saloon keeper from Stanton Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side was taken to court over serving this particular “meal” in his establishment, he was acquitted by a jury.

Committee of Fourteen

Determined to clean up New York City’s image, a citizens’ group that lobbied for the elimination of prostitution and gambling founded the Committee of Fifteen in 1900. Members of the group visited and inspected various locations of concern (saloons, dance and pool halls) and filed detailed records on each site.

In 1902 the evidence was collated in a comprehensive account, The Social Evil with Special Reference to Conditions Existing in the City of New York, and presented to the city’s 34th Governor, the Republican Benjamin Barker Odell, after which the Committee disbanded. The report’s final conclusion was that the Raines Law hotels were responsible for the curse of uncontrolled prostitution. The group’s work was continued by the Committee of Fourteen. Founded in 1905, the association’s explicit priority was the abolition of these hotels.

At the time, New York was known as a “wide-open” city in which public order was difficult to impose and maintain. The Tenderloin, the Lower East Side and Little Coney Island (around Third Avenue & 110th Street), were areas with a high concentration of saloons, brothels and “disorderly” dance halls. Sunday drinking was rife and many establishments had prostitutes soliciting openly in their back rooms. Corrupt officials and police officers were bribed to look the other way.

Having declared war on the Raines Law hotels, members of the Committee set out to have the legal provisions amended by making on-site investigations of “suspicious” establishments. They presented evidence of violations to the police, the State Department of Excise and the City Tenement House Department, to the brewers who supplied the saloons, and to real estate companies who owned the properties.

By 1911 most of the Raines Law hotels had closed up (although the law itself was not repealed until 1923), but the Committee remained active in the battle against alcohol, vice and “immorality.” Its members worked closely with the police and the courts to push for law enforcement in a political environment where the temperance movement gradually gained prominence and influence.

Campaigning alongside groups such as the Anti-Saloon League, they claimed that the prohibition of alcohol would eliminate poverty and eradicate vice and violence. It paved the way for the Eighteenth Amendment which was ratified in January 1919 and banned the sale and consumption of alcoholic drinks throughout the United States.

Prohibition

While the Raines Act was signed as a measure to curb drinking and deviancy, it created a massive loophole that gave countless businesses more freedom to serve liquor. Given that the law demanded the availability of bedrooms on the premises, the legislation inadvertently encouraged prostitution.

The Committee of Fourteen ensured the closure of the Raines Law hotels and promoted the argument for Prohibition. When the temperance movement finally won its battle to ban alcohol, opposition to and the dodging of the Eighteenth Amendment was set in motion. Loopholes were sought and found to acquire whatever alcohol that remained available. Drinkers posed as priests to obtain sacramental wine; they pestered their doctors to prescribe “medical” beer from the pharmacy to them.

Lawmakers had not learned the lesson from the Raines debacle that moral indignation alone does not produce effective legislation. Prohibition did not stop drinking, but it pushed the consumption of booze underground.

By 1925, there were thousands of speakeasy clubs located in New York City and profitable bootlegging operations sprang up around the nation. Prohibition boosted a booming industry of organized mobster crime which continued until Congress ratified the Twenty-First Amendment in December 1933, allowing Americans to raise a (legal) glass again.

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

BUDDHIST MONKS VISITING THE ISLAND

IN THEIR WONDERFUL SAFRON ROBES

ALEXIS VILLAFANE AND GLORIA HERMAN GOT IT RIGHT

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

NEW YORK ALMANACK

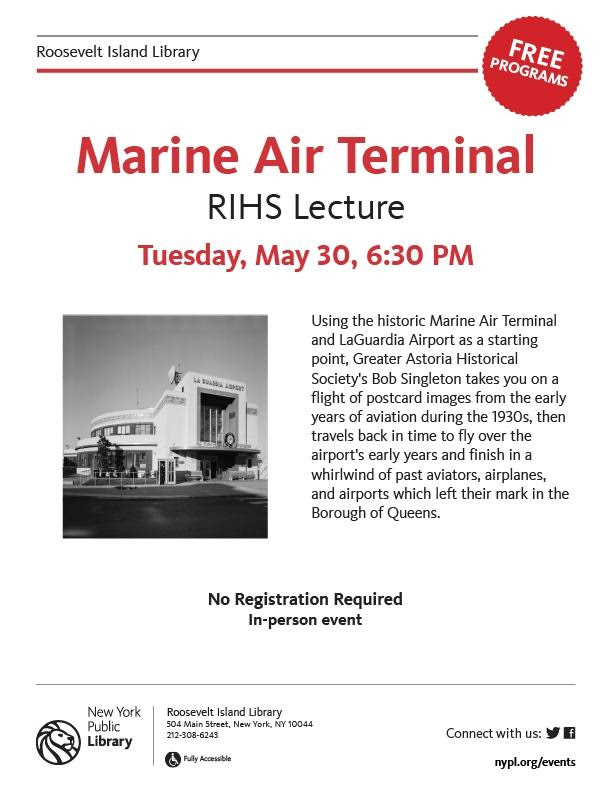

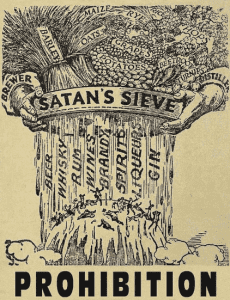

Illustrations, from above: Pro-Temperance cartoon from the 1900s (Getty Images); the original “loop hole”; Free lunch, 1911 by Charles Dana Gibson (Library of Congress); Barney Flynn’s Saloon on the corner of Pell Street and the Bowery, 1899; Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt in support of the Raines Law (Getty Images); and Satan’s Sieve anti-Saloon League Poster, 1919.

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment