Monday, July 24, 2023 – SO MANY DISCOVERIES CAME FROM NEW YORK

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, JULY 24, 2023

ISSUE# 1042

J Robert Oppenheimer in Schenectady

NEW YORK ALMANACK

J Robert Oppenheimer in

Schenectady

July 20, 2023

On October 21, 1941, 46 days before Pearl Harbor, The National Academy of Sciences Uranium Committee met in the office of Dr. William C. Coolidge, director of the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady. This top-secret meeting was historic for two reasons.

First, the Schenectady deliberations became the basis of the first U.S. governmental report unequivocally affirming the feasibility and urgency of producing an atomic bomb. At that time, U.S. and British scientists feared that Nazi Germany was working on the bomb.

Second, the meeting marked the beginning of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s high-level involvement in government efforts to develop an atomic bomb. Oppenheimer, of course, would later go on to lead the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico that designed, constructed, and detonated the first atomic bomb.

The National Academy of Sciences Committee Members

The Committee chair was Nobel Laureate Dr. Arthur Compton from the University of Chicago. Compton was appointed by Vannevar Bush, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s science advisor. There was question whether it was feasible to produce a nuclear fission bomb in time to make a difference in the Second World War.

The National Academy of Sciences, a most prestigious body, was ideally suited to be the final arbiter of such scientific questions and to appraise the military value of nuclear energy. The Committee, formed in April 1941, had met several times and had issued two previous reports. This was to be the last meeting and the final report of the Committee.

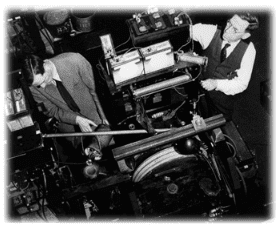

The vice-chair of the Committee was Dr. Coolidge, a physical chemist. Under Coolidge’s leadership, General Electric had gained considerable experience in nuclear research. In fact, GE had expressed to Compton willingness to make a nuclear reactor for producing plutonium on an experimental basis. Prominent GE scientists included Dr. Kenneth H. Kingdon and Dr. Herbert C. Pollock, who both would go on to work for the Manhattan Project at the Berkeley Radiation Lab.

Arguably the most famous member of the Committee was University of California physicist Ernest Lawrence, recipient of the Nobel Prize for the invention and application of the cyclotron at his Berkeley Radiation Lab. On September 21, 1941, he was visited in Berkeley by British physicist Marc Oliphant who described promising research related to the feasibility of making an atom bomb. (After his Berkeley meeting, Oliphant also visited Dr. Coolidge in Schenectady where he briefed him on the British research program).

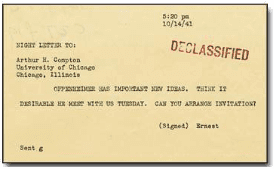

Britain, locked in a life and death struggle with Germany, desperately needed the U.S. to join the scientific race. Lawrence, convinced of the urgency of the task, brought his Berkeley colleague, theoretical physicist Robert Oppenheimer, into the Oliphant meeting with its secret revelations.

Lawrence was apparently indiscreet in involving Oppenheimer because Oppenheimer did not have security clearance. Furthermore, Lawrence felt that the National Academy of Sciences Committee needed the expertise of somebody of Oppenheimer’s caliber and prevailed upon chairman Compton to bring him to the Schenectady meeting as an “invited consultant.”

Other members of the Committee included: G. B. Kistiakowsky, Harvard chemist and explosives expert; W. K. Lewis, MIT chemical engineer; R.G. Mulliken, University of Chicago chemist; J.C. Slater, MIT physicist; J.H. Van Vleck, Harvard physicist and future Nobel Laureate. Also added to the Committee were engineering experts O. E. Buckley, Bell Telephone Labs and L. W. Chubb, Westinghouse Electrical and Manufacturing.

Dr. Coolidge offered to accommodate everyone at the Mohawk Club on lower Union Street.

The Committee Meeting and the Report

In light of the British progress in their atomic bomb program and other related developments in the U.S., the meeting of the National Academy Committee was called to determine the cost, development time, and potential destructiveness of an atomic bomb. The minutes of the meeting were taken by Lawrence and are archived at the U.C. Berkeley Bancroft Library.

The meeting exposed Oppenheimer for the first time to the latest research from U.S. and British scientists. His major contribution at the meeting was to estimate how much uranium -235 would be required to make the bomb. For the final report, he helped estimate the destructiveness of an atomic bomb explosion.

Much to the frustration of Compton and Lawrence, the engineers and chemists on the Committee refused to give an estimate of the cost and time necessary to process uranium and turn it into a bomb, the very purpose for which the meeting was called. There simply was not enough data. Therefore, Compton relied on his own rough estimate: 3 to 5 years and a total cost of several hundred million dollars.

As it turned out, it took three years and eight months to detonate the first bomb (in August, 1945). The final cost was $1.5 billion, but this involved using multiple methods of making fissionable material.

The final report, written over the next few weeks by Compton with input from Committee members and Oppenheimer, recommended that full effort toward making atomic bombs is essential to the safety of the nation and of the free world – a fission bomb of superlatively destructive power will result from bringing together a sufficient mass of element U-235.

The report was presented to Vannevar Bush on November 6, 1941 and to President Roosevelt on November 27. On December 7, 1941, Japan declared war on the United States. Germany followed suit on December 11.

The following year Robert Oppenheimer was chosen by director of the Manhattan Project General Leslie Groves (who was born in Albany) to lead the scientists and engineers of the Los Alamos Laboratory in the complex task of making the first atomic bomb. The stakes and time pressures were incredibly high. In many ways, Oppenheimer was an unusual choice. He had no management experience at all and he had been connected to persons in various left-wing groups deemed to be subversive.

Nevertheless, Oppenheimer proved to be an excellent choice and deserved the accolade, “Father of the Atomic Bomb.” The meeting in Schenectady, mentioned prominently in many histories of the atomic bomb, was an important milestone in his personal story as well as the nation’s quest for the atomic bomb.

Illustrations, from above: portrait of J. Robert Oppenheimer; portrait of William C. Coolidge; telegram from Lawrence to Compton; GE nuclear scientists H.C. Pollock and K.H. Kingdon in lab, 1940; and GE Buildings 5 and 37, home to the R & D Center.

Martin A. Strosberg wrote this essay for the Schenectady County Historical Society Newsletter, Volume 61. Become a member of the Society online at schenectadyhistorical.org.

WE ARE NOW ON TIK TOK AND INSTAGRAM!

INSTAGRAM @ roosevelt_island_history

TIK TOK @ rooseveltislandhsociety

CHECK OUT OUR TOUR OF BLACKWELL HOUSE ON TIC TOK

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEEKEND PHOTO

INTERIOR OF STEAM PLANT BELONGING TO

NYC HEALTH+HOSPITALS, NOW CLOSED

THE VIEW OF “DOUBLE TAKE” FROM THE ROOF OF THE SUBWAY STATION.

TO SEE MORE OF DIANA COOPER’S ART AND PHOTOGRAPHS CHECK OUT HER WEBSITE:

dianacooper.net

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

NEW YORK ALMANACK

www.tiktok.com/@rooseveltislandhsociety

Instagram roosevelt_island_history

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment