Friday, August 11, 2023 – HEADING SOUTH FROM 34TH STREET TO CANAL STREET

FROM THE ARCHIVES

FRIDAY, AUGUST 11, 2023

ISSUE# 1058

1820’S LITERARY RIVALRY:

MANHATTAN VS. BOSTON

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARSKAMP

1820s Literary Rivalry: Manhattan Versus Boston

August 7, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp

On November 2, 1820, the city of New York‘s Chamber of Commerce placed an advertisement in the Commercial Advertiser and other newspapers inviting merchant clerks to meet in Tontine Coffee House at 82 Wall Street and discuss forming of an organization that would be similar to Boston’s Mercantile Library (founded earlier that same year).

Nearly two hundred and fifty young men responded to the notice and joined the meeting which led to the creation of Manhattan’s Mercantile Library Association.

On February 12, 1821, the library opened in a large room on an upper floor of 49 Fulton Street under the guidance of its first librarian, John Thompson. Politically, it was an era of change. In Europe the year marked the death of Napoleon and the coronation of George IV; in the United States, President James Monroe had just begun his second term as the last of the so-called “Founding Fathers” in the post.

In the city of New York positive perceptions of opportunity and advancement took hold. It was felt that an “Era of Good Feelings” was about to open up.

Young professionals were inspired and challenged by people like John Jacob Astor, the son of a German butcher who had arrived in the United States after the Revolution and who, by 1820, had risen to be one of the city of New York’s wealthiest men.

The Association’s circulating library held a collection of seven hundred volumes in a mix of trade books and novels. Its mission was to provide the city’s growing population of young (often newly-arrived and socially mobile) clerks with an alternative to “immoral” entertainments and urban vices.

Books were championed as a means of cleaning up the city’s poor image of an incoherent mass of money-grabbing individuals. From our cynical perspective, it was astonishing that in commercial circles the realization dawned that a good library would be beneficial to the building of a civilized and cohesive society.

It may well be that their representatives had taken note of Benjamin Franklin’s words when he – the “ultimate bibliophile” – recommended the creation of lending libraries to stimulate learning.

Another (implied) aspect of the initiative was the growing irritation with rival Bostonians for their cultural snobbery and claims of intellectual superiority. New Yorkers were ready to take up the gauntlet.

Literary Manhattan

By 1820, with a population of somewhere between 120,000 and 150,000 inhabitants, Manhattan had become America’s most populous city. The small-town feel was vanishing slowly. The dirty streets were mostly unpaved and any form of infrastructure had barely been initiated. Pigs still ran lose all over town. Manhattan was an outhouse.

Early visitors were not impressed by the city’s poor standard of accommodation and hospitality. At night, the streets were as dark as a country town, lit only by smokey whale-oil (later: gas) lamps in an attempt to prevent crime. English novelist Frances “Fanny” Trollope, visiting in the late 1820s, complained bitterly about the New York’s philistinism in her book Domestic Manners of the American (1832). New York City was a haven for cash worshipers, an uncultured temple of

Mammon.

Boston in the early nineteenth century was New England’s nerve center with a network of railways and other means of transport. Thanks to the city’s economic success, it became a financial center with abundant capital available for social and commercial investment. By 1820, Boston was focus of the nation’s intellectual, medical and publishing activities.

Three decades later, the roles were reversed. The city of New York had become a magnet of internal migration with many of the country’s most ambitious and creative individuals being drawn to Manhattan which soon was establishing itself as America’s publishing capital, displacing Boston as a literary hub.

Many in Manhattan’s emerging literary environment produced work that was unmistakably American in style and subject, but authors were just as keen to promote both their individual and collective status as New York intellectuals – thinkers that were as distinct from New Englanders as they differed from their European counterparts.

Publishers of newspapers and magazines established their headquarters in Manhattan. The most significant contribution was made by the monthly Knickerbocker Magazine. Founded in 1833 by New York-born Charles Fenno Hoffmann, it set out to resist and correct the predominant Anglo-Saxon and Puritan narrative of American history.

Celebrating New York’s fountain of creativity, Washington Irving, William Cullen Bryant and other contributors would turn it into the most popular literary magazine of the age. The journal’s competitive tone had been set in the mid-1820s with the arrival of James Fenimore Cooper in Manhattan.

Literary Rivalry

Although born in New Jersey, James Fenimore Cooper was raised in Cooperstown, a pioneer settlement founded by his father on Otsego Lake. After finishing boarding school in Albany he attended Yale College, but was expelled for bad behavior after only two years as a student. This unhappy spell in his younger years filled him with a lifelong dislike of New England.

In 1819 William Tudor, co-founder and first editor of the North American Review, referred to Boston as the “Athens of America” for being “perhaps the most perfect and certainly the best-regulated democracy that ever existed.” Fenimore Cooper must have been irked and challenged by such statements.

Having inherited a fortune, Cooper briefly led the life of a country gentleman before taking up the pen. His debut novel Precaution, set in England and published anonymously in 1820, was followed a year later by The Spy, the first historical romance about the American Revolution. Its success encouraged him to move to New York and pursue writing as a career.

In 1823, he published The Pioneers, the first of a set of five novels called The Leatherstocking Tales, in which the novelist introduced the figure of Natty Bumppo, a mythic frontier man and the first American fictional hero.

In 1824, Cooper founded the Bread & Cheese Club which was a continuation of “Cooper’s Lunch,” a gathering of friends which had first met in 1822 in the back room of premises owned by bookseller and printer Charles Wiley in Reade Street, Manhattan.

This small printing shop would play a prominent role in the emergence of New York’s literary movement. Among a number of notable writers whose words went to print there were Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Wiley made Cooper a celebrity with the publication of The Spy in 1821.

Fenimore became the center of a group of about thirty-five members that included painters of the Hudson River School as well as writers such as William Cullen Bryant.

The Bread & Cheese Club was not a bohemian gathering of young artists, but a self-conscious coming together of the first generation of the city of New York’s creative and intellectual elite. Although living in Paris at the time, Washington Irving was made its Honorary Chairman in absentia.

The meetings of the Bread & Cheese Club were held fortnightly on Thursday afternoons and ended in the evening after dinner. African-American Abigail Jones was mentioned in Longworth’s Street Directory of 1824 as a pastry chef at 300 Broadway, running an establishment that was considered amongst the finest of the era. Cooper requested that she would prepare the Club’s dinners.

One of the circle’s chief aims was the promotion of America’s artistic competence, but just as important was the drive to compete with Boston’s literary elite and put the city of New York on the intellectual map. The rivalry was intense.

Bread & Cheese

New England and New Netherland clashed on many different levels. New England was a religious colony founded by refugees from a persecuted minority. New Netherland, established by the Dutch West India Company, was a trading post. The Dutch Reformed Church may have been the official religion, but citizens were free to practice other teachings in private. A substantial population of Huguenots, Quakers and Calvinists settled along the Hudson River.

New England did not allow such leniency. Feelings of hostility between the two communities originated in long standing tensions between England and the Low Countries which resulted in four Anglo-Dutch Wars over trade routes and colonial monopolies.

Today, New York City has a rich bread culture that reflects the diversity of the metropolis. Bread had a prominent place almost since the foundation of New Amsterdam when doughnuts were introduced by settlers from the Low Countries. Wheat was a profitable commodity crop for a number of notable New Yorkers, including the descendants of the Dutch Schuyler family.

By 1770, wheat was shipped from New York’s port across the Atlantic to Europe, the West Indies and down the coast. Over time, waves of Germans, Italians and East European Jews (bagels) brought loaves of their own. Once outlandish immigrant specialties, they soon reached every street corner of the city.

| Cheese arrived by a different route into America. When English Puritans crossed the Atlantic, they brought their knowledge of dairy farming to the colonies. Coming from predominantly agricultural areas, they set up cheese making operations in their areas of settlement.Production of Cheshire and Cheddar-style cheeses began in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629. As had been the case in Europe previously, cheese making on farmsteads was managed by women. For some considerable time, it remained almost a New England monopoly.With an increasing number of arrivals, English colonists began to press into former New Netherland territory from Connecticut. These Yankees, a disparaging name for New Englanders derived from the Dutch “Jan Kaas” (Jack Cheese), first took the eastern half of Long Island. They then moved westward, finally capturing New York’s port in about 1820 and dominated shipping activities until the Civil War.These expansive developments provoked a triumphant statement by Timothy Dwight, the fundamentalist preacher and President of Yale University (nicknamed the “Puritan Pope”), that New York was becoming “a colony from New England.” Such bragging must have infuriated the proud associates of Fenimore Cooper’s Bread & Cheese Club.Those who aspired to join the Club were chosen by ballot. The club’s very name was derived from the peculiar polls that were applied to admit or refuse new members. Critics have described the practice as somewhat eccentric. In doing so, they ignored its significance in view of the cultural rivalry between Boston and New York City.Considering Cooper’s aversion of New England and Puritanism (he was strongly attached to the Episcopal Church), the manner of selecting candidates was based on the following symbolic principle:Bread = New York = acceptance Cheese = New England = rejectionThese literary meetings and events lasted until 1827. Cooper himself had sailed to Europe in 1826 at the height of his popularity and the Club was dissolved soon after. The generation of “Knickerbockers” would continue his work in its drive to make New York City the nation’s cultural capital. |

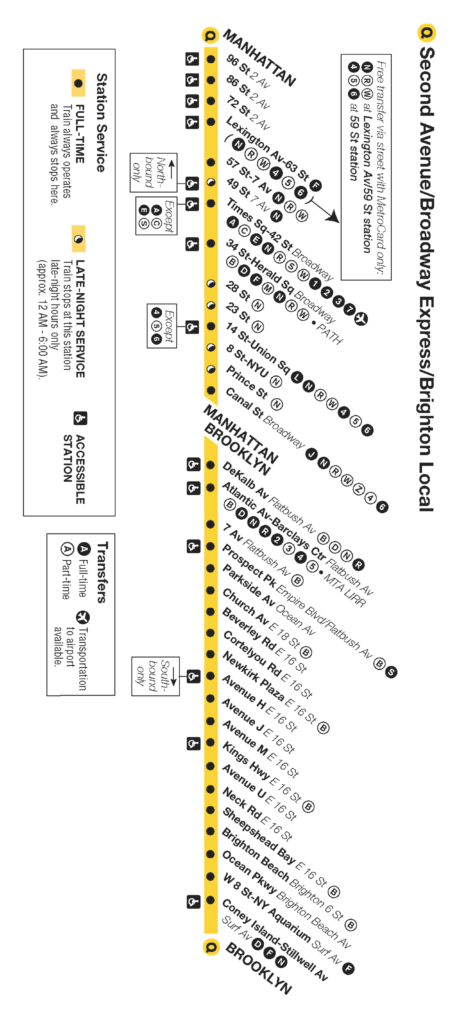

| TIME TO BITE THE BULLET AND STUDY THE ROUTE MAP FOR RIDING THE “Q” TRAIN ON AUGUST 28TH. |

WE WILL BE AT THE CHAPEL

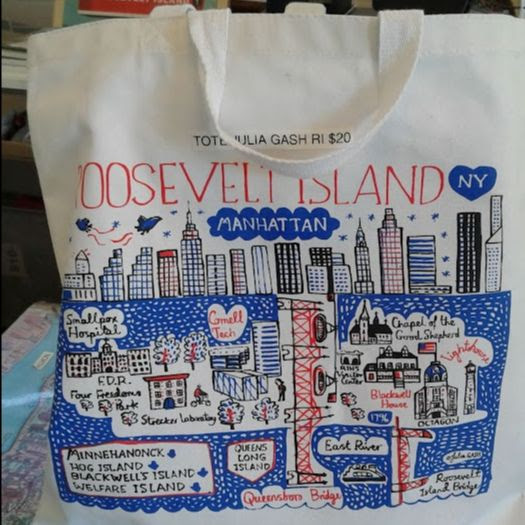

FLEA MARKET THIS SATURDAY STOP BY TO ORDER YOUR TAPESTRY THROW.

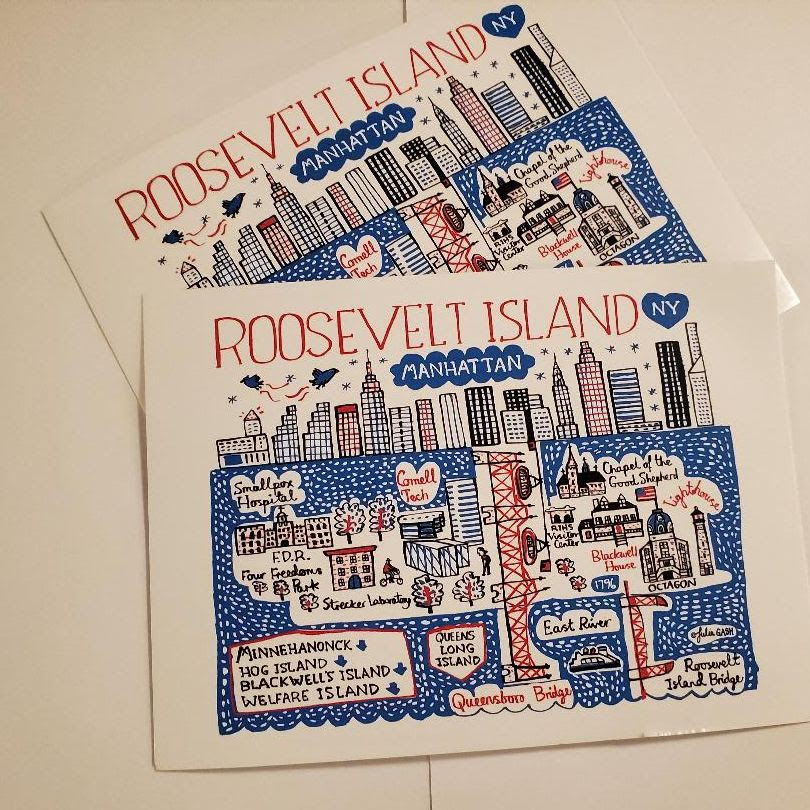

OUR JULIA GASH TAPESTRY THROWS WILL BE AVAILABLE VERY SOON. RESERVE YOURS TODAY FOR DELIVERY SOON.

THINK OF CUDDLING UP THIS WINTER UNDER A UNIQUE JULIA GASH (C) THROW!

STOP BY THE RIHS VISITOR CENTER KIOSK OR E-MAIL US AT ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM.

SEE THROW IN RIVERCROSS DISPLAY WINDOW.

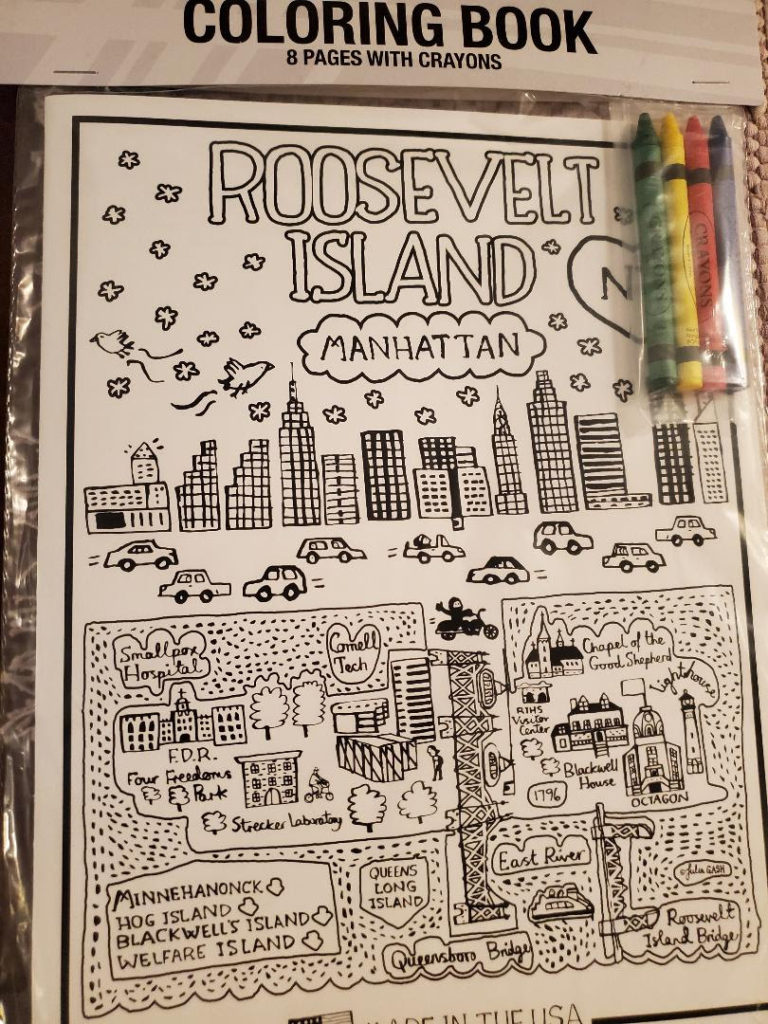

COME SHOP OUR JULIA GASH COLLECTION OF GREAT NEW ITEMS:

TAPESTRY THROW $70 UNTIL OCTOBER 1, $80 AFTER OCTOBER 1

MUGS $15-

TOTE $28-

LANYARD $8-

ORNAMENT $20-

COLOR BOOK $8-

POSTCARD $2-

LARGE POSTER $35 (NOT SHOWN)

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO: OUR SLOTHS ARE BACK IN STOCK. WE WILL BE AT THE FLEA MARKET ON SATURDAY READY FOR YOU TO ADOPT ONE,,,,,OR MORE.

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

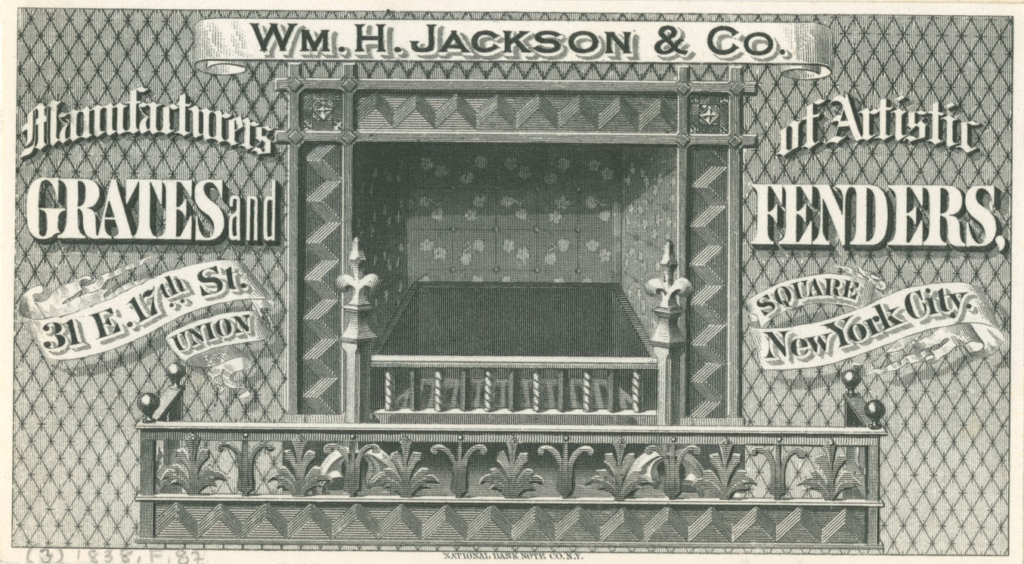

WM. H. JACKSON IS THE MANUFACTURER

OF OUR LAMP POST BASE LOCATED AT THE KIOSK CORNER.

PHOTO IS OUR LAMP BASE AT THE CORNER OF 60th STREET AND SECOND AVENUE

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

MAYA LEVANON-PHOTOS TIK TOK & INSTAGRAM

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Illustrations, from above: Francis Guy’s “Tontine Coffee House” (with flag on top), 1797 (New-York Historical Society); advertisement in the New York Commercial Advertiser of November 2, 1820; Knickerbocker Magazine cover (1856); the first edition of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Pioneers published by Charles Wiley; and William Cullen Bryant at work, ca. 1870s (New York Public Library).

JUDITH BERDY

www.tiktok.com/@rooseveltislandhsociety

Instagram roosevelt_island_history

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment