Wednesday, September 20, 2023 – STORIES OF THE ERA INCLUDED MUCKRACKING

TODAY

FROM THE ARCHIVES

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2023

GASLIGHT FOSTER:

OLD NEW YORK STORYTELLER

&

SOCIAL GEOGRAPHER

EPHEMERAL NEW YORK

ISSUE# 1080

Gaslight Foster: Old New York Storyteller & Social Geographer

September 6, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp

Having spent three weeks in Boston where he enjoyed an enthusiastic reception, Charles Dickens arrived on February 12, 1842, in South Street, Lower Manhattan, on the packet New York from New Haven. The city depressed him.

In his travelogue American Notes, he contrasted sun-filled Broadway with the filth of The Five Points. In the district’s narrow alleys the visitor was confronted with all that is “loathsome, drooping, and decayed.” Dickens described New York as a city of sunshine and gloom.

As Manhattan’s built environment expanded with the arrival of large numbers of newcomers, New Yorkers complained of being engulfed by blackness. The introduction of gas light in the streets alleviated the issue during night time hours, but distribution of the new technology was unequal. The monopolistic New York Gas Light Company bypassed deprived localities in favor of affluent or commercial districts.

Access to light in Manhattan, both natural and artificial, defined the difference between rich and poor neighborhoods, between safe and troubled environments. It marked the social inequalities of the urban landscape.

Pen Power

In 1906 Carl Hassman published his cartoon The Crusaders depicting a vanguard of writers and journalists as knights campaigning against corruption and corporate deceit. Many of the portrayed characters carry the pen as it were a warrior’s lance. The artist incorporated a number of vanguard journals in this imaginative army, including McClure’s Magazine and the satirical weekly Puck (famous for its cartoons).

That same year the term “muckraking” was introduced by President Theodore Roosevelt in describing the socially committed journalism of his day. Having borrowed the word from John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678), he criticized the press for focusing on corruption at the expense of more positive news. Journalists took this attack as a compliment and adopted the term as a badge of honor.

During the period between roughly 1890 and 1920 (the Progressive Era), muckrakers were investigative journalists who exposed fraud and duplicity in authority whilst highlighting social problems. Their aim was to generate public anger which would force lawmakers to intervene (or not). The muckrakers’ well-researched reporting differed from “yellow” journalistic practice by which newspapers sensationalized stories based on fiction and hearsay rather than factual information.

The muckraker was driven by both a quest for dramatic effect and a passion for justice. Coinciding with a growing readership and an emerging sense of urban identity, this type of journalism had been expanding gradually. In the city of New York, the scandal-focused approach and stylistic tone was set earlier in the nineteenth century by an enigmatic author named George Goodrich Foster.

Journeyman Journalist

Foster remains a shadowy figure as biographical information is scarce. He was born about 1812 in (probably) Vermont. With little or no formal education, he was – in his own words – a “dreamy poet” who took up journalism out of financial necessity.

Having moved to New York in 1842, his love for poetry became clear three years later when he published the first American edition of The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. In his introduction he praised the radical poet for his civilizing role in society. A student of French utopian philosophy, Foster’s thinking was influenced by Charles Fourier’s radical views on social change. He made his political engagement clear with the publication of The French Revolution of 1848. From the outset of his career, Foster acted as a commentator with reform in mind.

It may have been this particular aspect of his intellectual makeup that motivated Horace Greeley to hire him as a reporter. Founder and editor of the New York Tribune, the latter was a promoter of reform movements such as socialism, feminism, temperance and vegetarianism.

Foster soon established a reputation as an author of urban sketches and an observer of events that took place during New York City’s gaslight era. In engaging pieces, he attempted to pinpoint underlying sources of urban vice and crime and suggest solutions to the problems engendered by those living in poverty and destitution.

On a roving assignment (a “journeyman journalist” in his own phrase), he covered city life in all its aspects. Day or night, Foster hurried to report from fire or crime scenes; he joined public processions; covered local controversies; and commented on visits to New York by foreign dignitaries.

Foster was a regular guest at Manhattan’s House of Detention (known locally as “The Tombs”) which he outlined as a “shrine of petty larceny, drunkenness, vagabondism and vagrancy,” referring to his slum and prison tours in terms of “pilgrimages.” The use of the term is a reminder of the fact that journeys into the urban “jungle” were considered to be of great moral significance. Here too, Forster set an example.

Victorian London of the 1870s was a city of stark contrasts between affluence and squalor. In 1872 English journalist Blanchard Jerrold and French engraver Gustave Doré produced a book entitled London: A Pilgrimage. Together, the two explored the capital, visiting night refuges, lodging houses and opium dens.

In order to produce a telling record of the city’s “shadows and sunlight,” they also attended an event at Lambeth Palace and the Derby at Epsom Race Course. Doré’s 180 engravings, with their dramatic use of light and shade, captured the public mood.

Gaslight Foster

Few writers or journalists knew Manhattan by day or by night better than did George Foster. An urban chronicler, he roamed the streets and avenues, observed the razzmatazz of city life, and recorded events with a sharp eye and in a fluent and witty style.

His portraits of “swells” dining at Delmonico’s or gathering in oyster cellars; of Bowery derelicts and criminals; of “sidewalkers” hooking clients at The Five Points; of high-class “cyprians” operating in luxurious brothels (the “Golden Gates of Hell” in his words), provided his readers with juicy tales of life in a metropolis that by then had become the nation’s richest, most crowded and most vice-ridden center of activity. Foster’s snapshots helped forge the city’s identity and its distinct vocabulary (“New York City English“).

We shape our buildings and thereafter they shape us, Winston Churchill insisted in a speech of October 1943 concerning the rebuilding of the bomb-damaged House of Commons. The same statement can be applied to urban neighborhoods. In his descriptions, Foster dissected the metropolis into various “slices” of life animated by colorful characters. He was one of the first authors to offer a social geography of New York City.

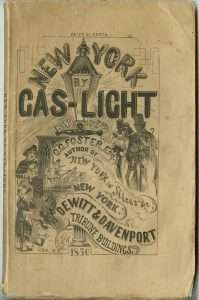

Foster’s columns proved popular and a collection of tales was published in 1849 as New York in Slices; by an Experienced Carver. In autumn 1850, he published a new series of sketches entitled New York by Gas-Light, with here and there a Streak of Sunshine which, as his publisher claimed, sold even better than the previous book.

Covering much the same topics, this set of stories concentrates on the “festivities of prostitution, the orgies of pauperism, the haunts of theft and murder, the scenes of drunkenness and beastly debauch, and all the sad realities that go to make up the lower stratum – the underground story – of life in New York!” (opening paragraph). The effort earned him the nickname “Gaslight Foster.”

What was the appeal of Foster’s columns? In his writing the author showed genuine sympathy for people caught in the meshes of poverty, a concern that was spiced by his contempt for politicians and religious dignitaries who defended the status quo and peppered by his hatred of the hedonistic lifestyles associated with a “sporting man culture.”

In his self-described role as an “experienced carver” of urban life, Foster practiced voyeurism with a social conscience. His success indicated an emerging wider sense of city identity that went beyond the Knickerbocker history of New York City.

That shift in urban awareness became evident when Benjamin Baker’s musical farce A Glance at New York in 1848 hit the stage, turning out to be one of the greatest theatrical successes up to that time. Following the adventures of Big Mose, a muscular firefighter, the play was a potpourri of filth and fury.

Its main character was presented as the “toughest man in the nation’s toughest city.” The play became a trailblazer for a new kind of drama populated by street-familiar characters that spoke directly to New Yorkers. Baker’s realistic and unsentimental image of the Bowery would have inspired Foster’s approach.

Foster’s work remains of interest to the social historian. Criminals, beggars and prostitutes may abound in his tales, but there is also ample attention to the plight of working people, to women struggling in sweatshops, to gangs that controlled districts, or to the aimless exploits of “b’hoys & g’hals” hanging out on street corners.

In spite of his stress on degradation and exploitation, Foster’s approach did help to instill a feeling of anticipation of “better days ahead.” The author believed that the city would “cure” itself from the “poison” of prostitution. Poverty and injustice could be eradicated. New York City was full of potential and an era of social change and reform was imminent. Foster’s messianic idealism never left him.

Decline & Demise

Throughout his writings, starting with the introduction to his Shelley edition, Foster showed an understanding of those being destroyed by the impersonal forces of poverty and destitution. His final book New York Naked was undated and appeared sometime in 1854. More substantial than his two preceding publications, it lacked their spark. By now he had become interested in Italian opera (he edited a Memoir of Jenny Lind, a compilation of printed items resulting from the from the adored Swedish singer’s 1850 tour) and his sketches of New York’s publishers, editors and writers remain of interest to historians of books and newspapers.

Beyond his publishing activities little is known of Foster during the years after he left the Tribune in 1849/50. Sometime before the end of 1853 he moved to Philadelphia, but must have hit hard times. In January 1855 he landed in prison for passing forged bank notes. He died on April 16, 1856, shortly after his release.

At best, Foster was a great storyteller, an author who could outline a scene in a single stylish paragraph through sharp characterisation. At worst, his writing deteriorated into sugary sentimentalism or petty finger-wagging. This was a thin dividing line. Many moralists had entered and described the sordid world of the metropolis, be it in London or New York, but only the work of great narrators survived and made an impact. Gaslight Foster was one of those.

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

GUASTAVINO CEILING ON ROOF OF ENTRACE TO CHATEAU FRONTENAC HOTEL IN QUEBEC CITY

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

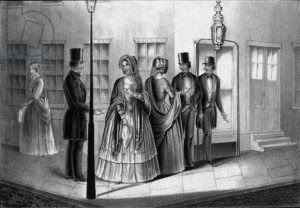

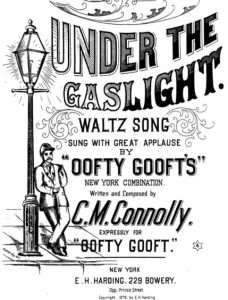

Illustrations, from above: “Prostitution: ‘Hooking a Victim’,” Engraving from New York by Gas-Light, 1850; Carl Hassman’s “The Crusaders,” 1906 (Library of Congress); Cover of 1879 sheet music for C.M. Connolly’s song “Under the Gas Light”; Cover of the first edition of Foster’s New York by Gas-Light (1850); and “Mayhem in Five Points,” an 1855 guidebook lithograph by an unknown artist.

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

MAYA LEVANON-PHOTOS TIK TOK & INSTAGRAM

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

www.tiktok.com/@rooseveltislandhsociety

Instagram roosevelt_island_history

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment