Friday, October 6, 2023 – MORE WONDERFUL HISTORY FROM NEW YORK ALMANACK

FROM THE ARCHIVES

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 6, 2023

Noah Webster’s Dictionary for

Independence

NEW YORK ALMANACK

ISSUE# 1093

Noah Webster’s Dictionary for

Independence

“Federal Procession” of nearly 5,000 citizens marched through Lower Manhattan in celebration of the ratification of the Constitution. The Order of the Procession was divided in ten divisions representing various trades and professions. One of those involved in the manifestation was a young Federalist and lexicographer by the name of Noah Webster.

Noah was a member of the Philological Society of New York. Founded in March 1788 for the purpose of “improving the American Tongue,” the Society was eager to take part in the event. Solemnly dressed in black, the philologists paraded in the Ninth Division with lawyers, college students and merchants.

Members of the Society carried symbolic props with them, including a flag depicting the “Genius of America” crowned with a wreath of thirteen plumes representing the States that had ratified the Constitution; a scroll displaying the principles of a “Federal Language” (the text of which has not survived); and the Society’s coat of arms.

From his early Dissertation on the English Language (1789) to his landmark dictionary of 1828, Webster would present himself as an indefatigable champion of American English. His name has become synonymous with the words “dictionary” and “independence.”

Teaching & Textbooks

Born in West Hartford, Connecticut, Noah was the son of a farmer who mortgaged the family business to pay for his son’s law studies at Yale University. During his freshman year on June 29, 1775, he witnessed George Washington moving through New Haven on his way to Cambridge to take command of the American Army. Under Noah’s musical leadership (he was a talented flautist), students escorted the General through town.

After his graduation in 1778, Webster experienced uncertain career prospects. A supporter of the Revolution, he was – like other young rebels – unable to find work as a lawyer. Struggling to decide which profession to pursue, he discovered the writings of the English lexicographer Samuel Johnson and turned his talent to education. The flow of printed materials from London had stalled because of the war between Britain and the thirteen colonies. Schoolbooks were in short supply. Noah set about filling the gap.

Webster published three textbooks: American Grammar (1784), American Reader (1785), and American Spelling Book (1789). He intended to introduce “uniformity and accuracy of pronunciation into common schools.” The fundamental idea had been formulated by Benjamin Franklin who suggested that “people spell best who do not know how to spell.” The more phonetic and logical, the better spelling would be. In political terms that meant opting for “democratic” clarity in linguistics. American English was to be purged of British aristocratic influence.

Webster succeeded in changing the French re and ce endings, theatre becoming theater, center instead of centre, and offense rather than offence; in replacing the English ou in words such has flavor, honor or humor (nabor instead of neighbour was never accepted); and in eliminating unnecessary double consonants (traveler for traveller; jeweler for jeweller).

Other changes Noah proposed were mocked and ridiculed: wimmen (women), blud (blood), or dawter (daughter) never caught on. In later years Webster backed off from his more radical spelling suggestions.

Seize the Moment

In Europe, the French Revolution had created hope and excitement, especially amongst young people. Renewal and liberation seemed concrete possibilities; poverty and injustice were to be eradicated here and now.

A similar sense of urgent anticipation was expressed by American revolutionary thinkers. “Now is the time” Webster wrote in an essay entitled “On Education” in the December 1787 issue of American Magazine. Let us seize the moment and “establish a national language as well as a national government.”

In 1789 Webster published his Dissertation on the English Language, dedicating the study to Benjamin Franklin. In the book, he suggested that the import of foreign terms by immigrants, the inclusion of Native American words, the multiplication of Americanisms, the re-interpretation of “old” British phrases, the introduction of scientific terminology and the proliferation of slang, made a specific American dictionary an essential tool for enriching American life and culture.

Webster concluded that these factors would lead to a gradual separation of the American tongue from the English. He insisted that the process should be accelerated through active intervention. The challenge to Americans was not just to create their own democratic system of government, but also their explicit manner of communication in which there should be no differentiation between classes and regions. Noah was an impatient man and time was of the essence.

Webster stood in the vanguard of those patriots who championed a distinctive “American language” that would be free from the corrupting influence of British English, but also protected from internal fragmentation. New nationhood provided unique opportunities for reform. Dissertation was a clarion call for linguistic unity and independence. The conviction that a “national language is a national tie,” was his guiding principle.

American Minerva

In 1793 Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington, recruited Webster to become editor of the newly founded Federalist newspaper American Minerva. Published on December 9, 1793, close to the Tontine Coffee House in Wall Street, it was the city’s first daily newspaper.

Aiming to contain the “earliest intelligence, collected from the most authentic sources,” the paper ran for 744 issues between 1793 and 1796 (it eventually became the New York Sun which finally ceased publication in 1950).

During that period Noah published a series of newspaper articles, political essays and textbooks. Working in an environment of news gathering, Webster must have been overwhelmed by the verbal richness of a rapidly expanding city and the vocal vitality of New York English. The journalistic experience may have served as a confirmation of his earlier “theoretical” reflections.

Webster returned to Connecticut in 1798. By then, his “Blue-Backed” American Speller had become a bestseller. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, about 100 million copies were in circulation. Only the Bible outsold the textbook.

Many of these “spellers” may have been pirated editions, but royalties were sufficient for him to devote the rest of his life creating an American dictionary (Webster’s battle against pirates and plagiarists would lead to the passing of the first federal copyright laws in 1790).

Over his lifetime, Webster published more than fifty books and pamphlets in a variety of fields. Most of his later scholarly work was carried out in his New Haven home at the corner of Temple and Grove Streets. Although his interest was predominantly in linguistics, he did pay attention to other social and communal issues. Public health was one of those.

Benjamin Rush was a physician and medical professor at the University of Pennsylvania. As one of the signatories to the Declaration of Independence, he was also a prominent politician with a strong concern for public health. When in 1793 an epidemic of yellow fever hit Philadelphia, killing nearly ten percent of the population, Rush assumed a leading role in battling the disease.

Webster teamed up with him and conducted a series of pioneering scientific surveys. In 1799 he published a Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, a review of available data and contemporary theories.

Dictionaries

British promoters of Empire at the time were keen to draw parallels with Imperial Rome. It was both an appealing analogy and a warning. Rome had been a civilizing force in barbaric times and it was Britain’s mission to play that role in the modern world. The Eternal City’s decadence should function as a constant reminder to rulers and administrators.

It was the task of grammarians to “fix” the English language, making it a fit vehicle for imperial ambitions just as Latin had been for Rome. A grand linguistic tradition had to be preserved for future generations, whilst banalities, vulgarities and foreign loan words had to be banned. In 1755, Samuel Johnson had published A Dictionary of the English Language, a two-volume folio work containing approximately 40,000 terms.

In his extensive use of illustrative quotations, Johnson looked backwards by selecting authors who “rose in the time of Elizabeth,” the “golden” age of linguistic excellence. Many linguists assumed that Johnson’s monumental effort would suffice for America as it did for Britain. Webster fundamentally disagreed.

In his ambition to standardize the nation’s language, Webster took the next step in 1806 by publishing A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. He did have a predecessor. The first dictionary compiled in America itself had been published in 1798 in New Haven by a fellow Connecticut lexicographer named Samuel Johnson Jr. (no relation of the English lexicographer; the extraordinary coincidence has created confusion among historians).

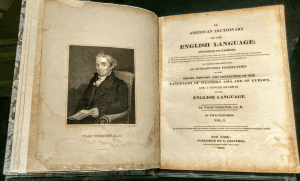

The first edition of Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1828. His classic volume was larger than Samuel Johnson’s by about a third. Native American speakers contributed terms such as moccasin, canoe and maize; from the French came prairie and dime; from Dutch, cookie and landscape; from Spanish, mesa and canyon; and from Mexican, hoosegow and stampede. Separate words were combined, creating the terms rattlesnake and bullfrog. Neologisms such as gimmick, currency and graveyard were also added.

Webster’s definitions frequently rambled out of scope. His religious and moral agenda shaped descriptions into mini-sermons rather than serve as mere clarifications of meaning. His etymology was flawed because he was unaware of research into the evolution of Indo-European languages from roots such as Sanskrit. Instead, his etymologies conform entirely to the interpretation of words as presented in the Bible.

Just like Samuel Johnson, Webster made ample use of biblical citations. Both were religious men, but the former focused on the Bible as a work of great literature; for the more orthodox Noah it was a tool for moral betterment. His dictionary was prescriptive as he tended to dictate how words should be used rather than record the way in which they were being used.

Webster’s dictionary was a cultural landmark, but a commercial failure. Its first edition sold only 2,500 copies. He was forced to mortgage his home to bring out a second printing and for the rest of his life he was dogged by a sense of failure. Noah died in 1843, almost forgotten and unrecognized.

Legacy

Webster’s legacy was secured by the efforts of editors who “cleaned up” his dictionary. In 1853 publishers George and Charles Merriam achieved success selling the dictionary as a national symbol through a method of “testimonial” advertising. Having sent out gift copies to many prominent figures, they used standard signed thank-you letter as proof of endorsement, angering Washington Irving and others who did not want to be associated with Webster’s enterprise.

American English would pursue its own development, in spite of Webster not because of him. His real legacy was the persistent call for an American literature by advising authors to seek detachment from English literary models.

What debases the genius of my countrymen, he cried out, is the “implicit confidence they place in English authors, and their unhesitating submission to their opinions.” If America desired to produce its own literary heroes, the nation had to minimize its dependence on Anglo-European examples. This was the rebellious message that resonated in the ears of subsequent generations of writers and artists.

When on July 24, 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson delivered an oration entitled “Literary Ethics” at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, his carefully crafted argument reflected the spirit of Webster. As creators we are grateful for a great history, he told his audience, but “now our day is come.” We will live for ourselves “not as the pall-bearers of a funeral,” but as creators of the present by putting “our own interpretation on things, and our own things for interpretation.”

Nearly half a century earlier, Webster had expressed the same viewpoint with an identical sense of conviction and immediacy.

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

OUR JULIA GASH TAPESTRY THROWS HAVE ARRIVED.

48″ X 60″ MADE IN USA

WE ARE TAKING ORDERS AND SELLING THEM THIS WEEKEND.

SEND YOUR ORDER TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

New York International Airport, then commonly called Idlewild Airport, when new around 1950. Pan American Airlines aircraft is on a taxiway passing over the Van Wyck Expressway.

Andy Sparberg

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

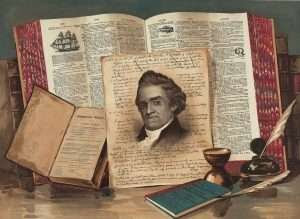

Illustrations, from above: The New York Grand Federal Procession, July 22, 1788, passing Bowling Green, from Martha J. Lamb’s History of the city of New York: its origin, rise, and progress (Volume 2), 1882; Noah Webster, “The Schoolmaster of the Republic,” print produced by Root & Tinker, New York, 1886 (Library of Congress); Front page of the inaugural edition of the Federalist newspaper American Minerva from December 9, 1793; the title page of Webster’s 1828 edition of the American Dictionary of the English Language; and Korczak Ziolkowski’s tribute to Noah Webster (early 1940s) in Blue Back Square, West Hartford, Connecticut.

JUDITH BERDY

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

MAYA LEVANON-PHOTOS TIK TOK & INSTAGRAM

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

www.tiktok.com/@rooseveltislandhsociety

Instagram roosevelt_island_history

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment