Week of March 23-30, 2024 – A STREET WITH A RADICAL HISTORY

WEEK OF

MARCH 23-30, 2023

VILLAGE RADICALS

&

A DELIRIUM OF

DEPORTATIONS

ISSUE # 1210

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARSKAMP

TIME OUT: I WILL BE WORKING EARLY VOTING THIS WEEK AT OUR ISLAND POLL SITE IN THE GALLERY RIVAA. STOP BY TO CAST YOUR BALLOT IN THE PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY AND SAY HELLO. BE BACK AFTER EASTER WITH MORE STORIES.

Village Radicals & A Delirium of Deportations

March 21, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp Leave a Comment

Manhattan’s MacDougal Street was named after merchant Alexander McDougall, a Scottish immigrant who hailed from the Isle of Islay. A rebellious character, he had been actively involved in the Revolutionary War.

In later years, McDougall represented New York in the Continental Congress and became the first President of the Bank of New York. Until their reckless destruction in 2008 to make space for New York University’s law school, the buildings from number 133 to 139 were landmark addresses in the history of Greenwich Village.

Manhattan’s MacDougal Street was named after merchant Alexander McDougall, a Scottish immigrant who hailed from the Isle of Islay. A rebellious character, he had been actively involved in the Revolutionary War.

In later years, McDougall represented New York in the Continental Congress and became the first President of the Bank of New York. Until their reckless destruction in 2008 to make space for New York University’s law school, the buildings from number 133 to 139 were landmark addresses in the history of Greenwich Village.

Village of Dreams

During the last decades of the nineteenth century, Europe’s major cities were in the grip of militant radicalism. Vienna experienced a number of uprisings. Rumors that the Emperor himself was a target abounded in and around the capital, especially since the assassination in 1898 of Empress Elisabeth of Austria by the Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni.

Born in 1869 in Bohemia (then part of the Austria-Hungarian Empire), Hippolyte Havel was educated in Vienna where he associated himself with radical circles. Anarchism in the late nineteenth century was literally a “movement on the move.”

Activists lived under constant threat of arrest and moved from country to country. Many would eventually end up in the United States. American anarchism was established by political refugees from Paris, London, Madrid, Rome, Berlin, Moscow or Vienna.

Havel had started his career as a journalist, but was arrested in 1893 after delivering a blazing May Day speech. Having served eighteen months in prison, he was deported from Vienna. Soon after he was re-arrested for taking part in an anarchist demonstration in Prague. Expelled from the country he traveled to Germany, spent time in Zurich and then moved on to Paris.

After a series of bomb attacks in the 1890s, the French authorities were not inclined to tolerate subversive activities and by 1899 Havel was living “down and out” in London. There he met the political activist Emma Goldman whose orthodox Jewish family had fled anti-Semitism in Lithuania and settled in the United States in 1885. The pair became lovers.

In September 1900 Havel accompanied Goldman to Paris where an attempt was made to stage an international anarchist congress (for which Peter Kropotkin wrote a contribution on Communism and Anarchy), but the police intervened and prevented the event from taking place.

Returning with Emma to the United States, Havel settled in Chicago. He was one of six anarchists arrested and briefly detained in the city on September 7, 1901, accused of plotting with Leon

Czolgosz who had murdered President William McKinley on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York.

All over the nation anarchists were hunted down, but repression breeds resistance. Havel had no intention of being silenced.

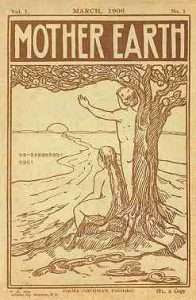

In 1903 Emma Goldman had settled in an East Village tenement at 208 East 13th Street. When in 1906 she founded the journal Mother Earth (“A Monthly Magazine Devoted to Social Science and Literature”), she ran her office from the neighboring tenement (No. 210). Arguably the most influential anarchist journal in America before the First World War, it was banned by the federal government in 1917. Havel became her associate and collaborator even though their love affair had ended.

Art & Anarchy

A flamboyant character, Havel spoke several languages and expressed himself in a fluent style of writing, but he was not academically minded and never produced a full-length book. A revolutionary with a fondness for drink, Havel’s heroes were activists who adhered to Johann Most’s “propaganda of the deed” and accepted violence as a legitimate means of achieving political ends.

Historically, creative milieus have clustered in urban areas where housing was relatively cheap, attracting a diverse group of migrants, artists and students. These densely populated and overcrowded sites were soon littered with small workshops, bakeries, cafés and eateries.

Their maze-like streets proved difficult to police and offered a perfect hiding place for controversial thinkers and activists. Interactions were intense, forging tight and often rebellious community bonds.

Although the image of Greenwich Village as a progressive “republic” of free spirits won popular acceptance during the mid-1910s, it reflected only a small part and brief period (between 1913 and 1918) of local life.

Most residents were not bohemians. Their lives were not shaped or determined by the influx of young artists and activists, but by continuous migration and changes in ethnic composition that affected local conditions.

The small Village community of radicals centered on Washington Square where Fifth Avenue ends at Stanford White’s triumphal arch. Inspired by his experiences in Vienna and Paris, Havel recognized the primacy of “creative spaces” such as cafes, salons and cabarets where anarchist ideas could be discussed away from the formality of political discourse.

Such gatherings cemented solidarity between anarchists and artists which he considered crucial for the movement’s expansion. They were natural allies who challenged the bounds of conventional thought in order to bring about renewal, be it artistic or social.

The association of anarchism with the arts had been stressed as early as 1857 by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. In his essay on the painter Gustave Courbet the philosopher stressed the social mission of the artist by giving visual form to the struggle of working classes in a bourgeois society.

Havel brought his European heritage to Greenwich Village. He argued that the cultural avant-garde had a vital role to play in the revolutionary struggle.

Playwright Eugene O’Neill served a brief apprenticeship as co-editor of Havel’s journal Revolt before it was closed down for its opposition to the nation’s involvement in World War One. This

involvement sparked the writer’s interest in anarchist activity (he portrayed Havel as Hugo Kalmar in his play The Iceman Cometh).

Polly’s Restaurant & The Liberal Club

Havel claimed to have come up with the idea for a Village restaurant as a platform where radicals could eat and talk revolution. In 1913, his then lover Polly Holladay opened a modest bistro in the basement of a townhouse at 137 MacDougal Street located just below Washington Square Park. Originally named The Basement, it became known as Polly’s Restaurant.

Born in Evanston, Illinois, Polly immersed herself in the bohemian atmosphere. Havel served as cook and waiter, while she handled finances and engaged with customers. The bistro’s walls in yellow chalk paint were hung with local artists’ work.

With its wooden tables crammed together, Polly’s soon became an alternative eatery of choice for a set of patrons that included novelists Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson, playwright Eugene O’Neill, political activist Emma Goldman as well as the imposing figure of Max Eastman, editor of the magazine The Masses. It was a creative space where Village residents sat down to discuss art, politics and revolution.

Havel took center stage for his verbal power and “volcanic outbursts.” He gained notoriety for addressing patrons of the restaurant as “bourgeois pigs” (throwing insults at clients was a feature of the European cabaret culture). He always reserved a table and bench for Emma Goldman and her lover, fellow Lithuanian activist and editor of her journal, Alexander Berkman.

The bistro was home to the Heterodoxy Club, a woman’s forum founded in 1912 by the extraordinary Marie Jenney Howe (biographer of the French novelist George Sand) to lunch and discuss radical feminist strategies.

A “heterodite” defined herself as a woman “not orthodox in her opinion” which allowed for members of diverse political views and sexual orientations to exchange ideas and in doing so define American feminism (a new word at the time, borrowed from the French).

The upstairs space from Polly’s basement was occupied by the Liberal Club which, founded in 1912, billed itself as a social meeting place for “those interested in new ideas.” Henrietta Rodman was the most outspoken of its female members in their demands for “free love,” birth control and equal rights.

Several of them took part on March 3, 1913, in the eventful women’s suffrage procession along Washington’s Pennsylvania Avenue (the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration).

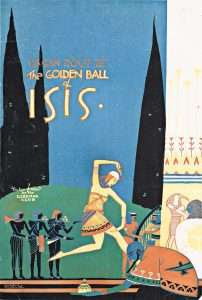

The club also became notorious for its annual costume ball, a bacchanalian event known as the Pagan Rout, held at nearby Webster Hall at 125 East 11th Street. The location became even more popular when a passage was created into the neighboring building where the brothers Albert and Charles Boni ran their Washington Square Bookshop.

Books & Plays

Opened at 135 MacDougal Street in 1913, the Washington Square Bookshop gained a central place in the Village community. Members of the Liberal Club used the shop as a library, “borrowing” books to read in the comfort of the club and return them when finished.

The Boni brothers never made a profit out of the business. In 1915, they decided to give up bookselling and focus on publishing instead (their company would eventually become Random House). They sold the shop to Frank Shay.

Born Frank Xavier Shea in 1888 in East Orange, New Jersey, he changed the spelling of his name in order to associate himself with Shays’ Rebellion (an armed uprising led by Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays against tax rises in Western Massachusetts). He would run the Washington Square Bookshop for about two years and became closely involved with the arrival of theater in the Village, both as an actor and a publisher.

In 1916, the Provincetown Players opened the Playwrights’ Theatre at 139 MacDougal Street, next to Polly’s Restaurant and the Liberal Club. This collective of artists, writers and theatre lovers produced plays for two seasons in Provincetown, Massachusetts (1915/6), and six seasons in New York City (1916 to 1922).

Shay played the role of Scotty in their production of Eugene O’Neill’s Bound East for Cardiff, the play that launched the dramatist’s career. From his bookshop he published three volumes of The Provincetown Plays (1916), landmark collections of the group’s earliest productions.

Shay’s activities were interrupted when conscripted in 1917. He fought the draft on the basis of his pacifist beliefs, but did not succeed. He served in the Headquarters Company of the 78th Division in France and saw action in the battles of Saint-Mihiel and the Forest of Argonne.

Demobilized in June 1919, Shay returned to New York and opened a tiny bookshop at 4 Christopher Street, West Village, and remained engaged in publishing volumes and anthologies of plays. He kept in touch with the latest literary developments.

When novelist and poet Christopher Morley visited the shop in April 1922, he reported his first sight of the blue-covered first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, recently published by Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Company in Paris.

Deportations Delirium

Politically the Village was no longer the same as the First Red Scare took hold of its community. From April through June 1919 several bombings were carried out nationwide aimed at judges, politicians and law enforcement officials, including the Washington home of newly appointed Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer. The latter responded by creating a division of intelligence agents led by the young lawyer J. Edgar Hoover. The aim was to crush the “Reds.”

Tensions between activists and agencies increased sharply after the raid on the headquarters of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the East Village on November 11, 1919, leading to violent street clashes between opposing political camps. The 1917 Espionage Act and the 1918 Anarchist Exclusion Act were used to justify the onslaught. Temporarily, Village radicalism went underground.

On December 21, 1919, the Federal government assembled 249 “undesirable” left-leaning East European immigrants onto the US Army transport Buford (nicknamed the “Soviet Ark”) and expelled them to Russia.

It was reported in The New York Times as “A merry Christmas present to Lenin and Trotsky.” Or as the jubilant Saturday Evening Post put it: “The Mayflower brought the first builders to this country; the Buford has taken away the first destroyers.”

On January 16, 1920, the ship arrived in Finland and the deportees were transported by train to the Russian border. Amongst them were Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman.

The impact of the intervention caused a persecution frenzy. Palmer and Hoover organized a massive roundup of radicals. By early January 1920, the Palmer Raids led to thousands of arrests and hundreds of deportations (described in 1923 by Louis F. Post as the “Deportations Delirium”).

The project turned into a festival of retribution based on dubious constitutional grounds and a disregard for civil rights. It should be a reminder to who partake in the present debate on democratic values.

An extremist is someone who engages in violence for political or religious ends. Any definition of radicalism must therefore be fit for purpose in a particular context. What matters is how people act, not what they think. Only those who resort to (or incite) extreme methods should be confronted.

Democracy encourages contrarian debate, even if an argument may offend the majority or unsettle the status quo. No nation can progress without heretics. Galileo was sentenced to life imprisonment for his perceived insult of the church while claiming the earth orbited the sun.

THURSDAY & FRIDAY PHOTO

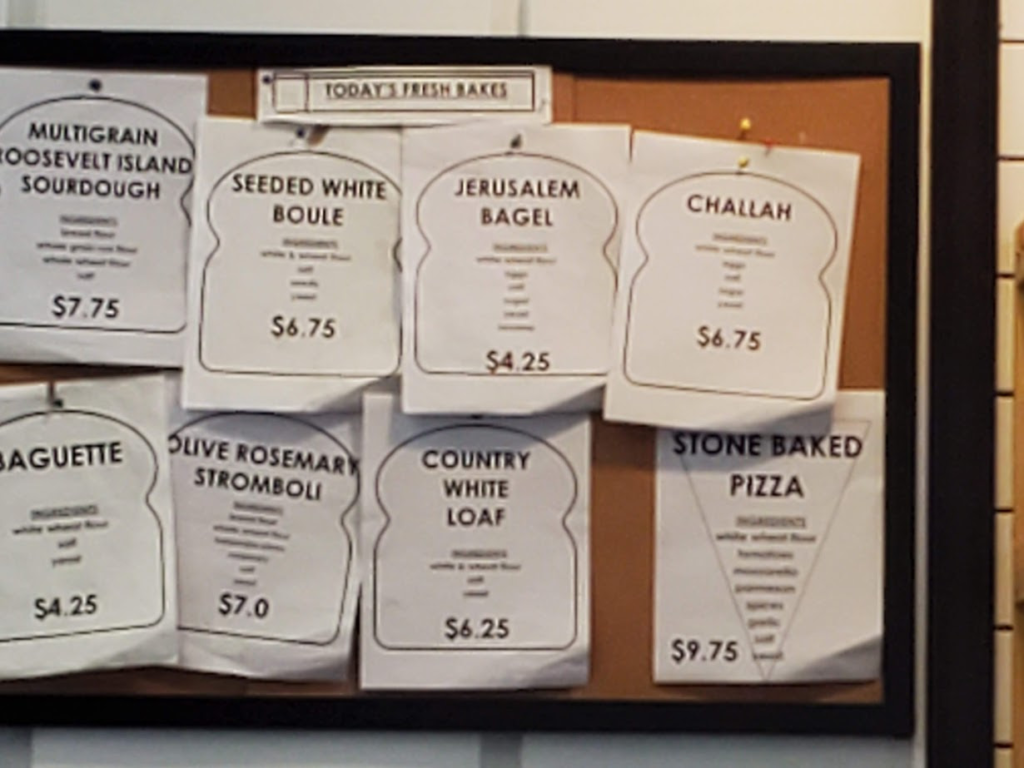

LIST OF DAILY BAKED GOODS AT MEDITERRANEAN EATERY

NINA LUBLIN., THOM HEYER, JOAN BROOKS, & GLORIA HERMAN GOT IT RIGHT

Text by Judith Berdy

Illustrations, from above: Demolition of historic McDougall Street buildings in 2009 (courtesy Village Preservation); Edwin Wright Woodman’s “Portrait of Havel,” published in September 1901 in The Minneapolis Journal (Library of Congress); cover of the inaugural issue of Emma Goldman’s anarchist magazine Mother Earth, March 1906; Polly’s Restaurant at 137 MacDougal Street, NYC circa 1915; poster of the Liberal Club’s annual ball, “Pagan Rout III,” 1917, signed by “Rienecke” (probably Rienecke Beckman); and the I.W.W.’s New York City headquarters after a Palmer Raid, 1919.

CREDITS

MAYA LEVANON-PHOTOS TIK TOK & INSTAGRAM

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

www.tiktok.com/@rooseveltislandhsociety

Instagram roosevelt_island_history

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment