Weekend, April 13-15, 2024 – ALL SPORTS ARTICLES THIS WEEKEND

APRIL 13-15, 2024

SPORTS WEEKEND

SPECIAL

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Brooklyn Royal Colored Giants Baseball in

Northern New York

An 1896 ‘Old Timers’ Boxing Event in New York City

Babe Ruth, Sports and 1920s Identity Politics

The Black Cyclone & The Unbearable Whiteness of Cycling

ISSUE # 1220

These are some articles from New York Almanack, To sse the list of dozens of more sports articles, go to

newyorkalmanack/sports

Brooklyn Royal Colored Giants Baseball in Northern New York

August 11, 2023 by Maury Thompson 1 Comment

“A cloudburst of the harshest kind ever known in local baseball history,” hit Port Henry on Lake Champlain, June 14, 1923. It was not the kind of cloudburst of rain which disrupts a ballgame and sends fans scrambling, but a cloudburst of talent that finds local fans cheering for the visiting team.

The Brooklyn Royal Colored Giants professional baseball team defeated the Port Henry semi-professional team, comprised primarily of local players, 20-1 in a game the home team was not expected to win. Sourian, the Giants pitcher, had 19 strikeouts.

“The locals had no more of a show against this aggregation than a kitten would have against a tiger,” the Essex County Republican reported on June 22, 1923.

The goal of Port Henry management was to test the draw that a nationally-recognized team would have in this segregated Essex County mining village, where semi-professional and amateur baseball had long been a pastime.

Booking the Brooklyn team was a matter – as in real estate – of location, location, location.

Port Henry was a convenient stop on the way from Burlington, where the Royal Colored Giants had won two of three games against the University of Vermont the previous week, to Montreal, where the Giants were scheduled to play the next day.

Bringing in the “fast and classy aggregation” was expensive. “It cost the Port Henry team’s management so much to get this team that it is necessary to raise the admission price to 75 cents (the equivalent of $13.38 in 2023 dollars) for gentlemen and 50 cents for ladies,” the Ticonderoga Sentinel reported on June 7. “If the attendance of the game warrants it, Port Henry will book some more high-class teams like the Giants.”

Typically, 25 cents was the standard admission to baseball games in various towns in that era.

Fans got their money’s worth, according to the Essex County Republican. “Fans who witnessed the game will perhaps wait many a day before they will see a ball team in action as that of the Royal Colored Giants.”

John Wilson Conner, owner of the Brooklyn Royal Café, established the Royal Colored Giants in 1905. Over the decades, the team played in various Negro leagues, starting in 1907 in the National Association of Colored Baseball Clubs of the United States and Cuba.

The Royal Colored Giants also played against semi-professional white teams.

Conner later sold the team to Nat Strong, a white booking agent and promoter from New York City, who owned the team when it played at Port Henry.

In 1923, the same year the team played at Port Henry, the Royal Colored Giants was a charter member of Eastern Colored League, and played in the league through the 1927 season, according to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

The Royal Colored Giants placed third in the league in 1923, with a .500 season record.

The team disbanded in 1942.

An 1896 ‘Old Timers’ Boxing Event in New York City

January 26, 2023 by Guest Contributor

The following essay was published in the “The World Of Sport” column in The [Troy] Daily Times on December 15, 1896.

Pugilistic champions of other days and of the present time passed in rapid review before a crowd of 2,500 sports in the Broadway Athletic Club last night. There was a rare galaxy of them.

Jem Mace [James Mace, born in 1831-died in 1910], who was champion of England thirty-five years ago, and Mike Donovan [Michael J. Donovan, see below, b. 1847 – d. 1918] were the stars of the occasion. The kaleidoscopic entertainment was arranged for their benefit and they will divide $2,400 between them.

Preceding Mace and Donovan, however, there appeared more than one man who has played a larger part in fighting and done more to make ring history. There were champions of a quarter of a century ago and champions who in this day are prepared to defend the titles to which they lay claim.

Well known men and well known faces abounded. Thomas E. Byrnes, ex-superintendent of [New York City] police was present, witnessing a boxing entertainment for the first time since he left the police ranks. Then there were Bob Pinkerton [co- manager of the Pinkerton Agency, 1848-1907], H. K. Knapp [Harry Kearsarge Knapp, 1864 – 1926, thoroughbred racing executive], Harry Buermeyer [a rower call the “father of American athletics,” 1864-1926], Phil. Dwyer and his understudy, Colonel Abe Daniels; H. G. Crickmere [Henry G. Crickmere, 1839-1908], secretary of the Westchester Racing Association; Al Johnson [baseball executive Albert Loftin Johnson, 1860-1901], Frank Simpson [football coach Frank William Simpson, 1871-1929], Jockey Taral [Hall of Fame Jockey Fred Taral, 1867-1925], Dave Holland, Jack Lawrence [John Lawrence, ca. 1823-1896], who trained [American Bare-knuckle Heavyweight Champion] John Morrissey in his day; George E. Smith, better known as “Pittsburg Phil” [George Elsworth Smith, gambler and thoroughbred horseman, 1862-1905], Ed Kearney, Jr., Gottfried Walbaum [operator of Saratoga Race Course], Ike Thompson, Al Smith [probably future New York Governor Al Smith, 1873-1944], Dan Noble [19th century gambler and boxer], Ed Stokes [possibly Edward C. Stokes, later Governor of New Jersey, 1860-1942], Ed Gilmore [19th century boxing promoter], Timothy D. Sullivan [Timothy Daniel Sullivan, Tammany Hall leader, 1862-1913], Tony Pastor [Antonio Pastor, variety performer and theater owner known as the “Dean of Vaudeville,” (1837-1908] and Citizen George Francis Train [traveler and entrepreneur who inspired Jules Verne’s novel Around the World in Eighty Days, 1829-1904].

It was 10:30 o’clock when the real stars, Jem Mace and Mike Donovan, appeared. Both veterans wore long white flannel trousers and were stripped above the belt. “Parson” Davies [Charles E. Davies, Chicago sporting man, manager and promoter, 1851-1920], master of ceremonies, explained that the bout was friendly, and that no decision would be announced.

Donovan was decidedly more active on his feet and proceeded to dance around the Englishman in rapid style, at the same time tapping him with his opened gloves. Mace, in spite of his sixty-five years, was by no means slow and used his left constantly.

In the second round Donovan got in an extra hard slap and Mace stopped to remove his upper row of false teeth, which he carelessly threw to his seconds. Jem was a bit tired toward the end of the third round and said, breathlessly: “Don’t go so bloomin hard, Mike!”

The fourth round was the wind-up, and the old fellows went at it in lively fashion. Mace held his own and all the crowd yelled “Draw! Draw!” when it was all over. John L. Sullivan [first heavyweight champion of gloved boxing, 1858-1918] and “Jim” Corbett [James John Corbett World Heavyweight Champion, and the only man who ever defeated John L. Sullivan, 1866-1933] received an ovation during the evening.”

Note: During his professional boxing career Mike Donovan, later known as “Professor” for his teaching prowess, fought John Shanssey in a bout refereed by Wyatt Earp in Cheyenne, Wyoming in the late 1860s. At the end of his career he became a boxing instructor at the New York Athletic Club where he taught Theodore Roosevelt and his sons how to box.

Illustrations, from above; Professor Mike Donovan (on right) helping his son train in boxing, ca. 1910s; and a portrait of Jem Mace.

This essay has been edited and annotated by John Warren. More stories about the history of boxing can be found here.

Babe Ruth, Sports and 1920s Identity Politics

The Roaring Twenties saw the collision of an emerging culture of celebrity with the established popularity of sports, creating one of the twentieth century’s most enduring personalities — baseball hero Babe Ruth.

In 1928, Ruth not only led the New York Yankees to their third World Series victory, he also threw himself into politics, campaigning enthusiastically for New York State governor and Democratic presidential nominee Al Smith. Smith’s liberal and progressive platform appealed to diverse, working-class Americans, often marginalized by the policies of other politicians.

Ruth’s enthusiasm for Smith reinforced this appeal, but also brought backlash from voters, especially nativist, who viewed Smith and his admirers as un-American. Joined by teammates and other stars from the sporting world, Ruth’s support for Smith was a new and exciting development in presidential politics and showed the growing importance of sports in American culture and the role of identity in politics.

The New York State Museum will host “Babe Ruth Gets Political: Sports and Identity Politics in the Roaring Twenties,” a program with Stephen Loughman and Dr. Robert Chiles set for Thursday, November 17th, at the Huxley Theater in Albany.

New York State Museum Curator of Sports, Stephen Loughman, will present a short history of the “House that Ruth Built” and discuss New York Yankees-related artifacts in the Museum’s collection, including a recently donated Babe Ruth signed baseball.

Dr. Robert Chiles is a senior lecturer at the University of Maryland and, in 2021, became a Research Associate in History with the New York State Museum. He is co-editor of New York History, a member of the editorial board of The Hudson River Valley Review, and the host of “Empire State Engagements.” Chiles has written numerous pieces on New York State history, including in his first book, The Revolution of ’28: Al Smith, American Progressivism, and the Coming of the New Deal (Cornell Univ. Press, 2018); as well as in articles for Environmental History, the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, New York History, and op-eds for Newsday, the New York Daily News, and the Albany Times Union.

Stephen Loughman is the Curator of Sports at the New York State Museum. He has presented several times on New York State sports history and is working to build the Museum’s sports collections.

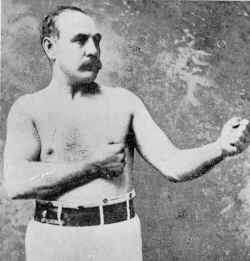

The Black Cyclone & The Unbearable Whiteness of Cycling

The invention of the wheel has been celebrated as a hallmark of man’s drive for innovation. By the 1890s, Europe and America were obsessed with the bicycle. The new two-wheel technology had a profound effect on social interactions. It supplied the pedal power to freedom for (mainly white) women and created an opportunity for one of the first black sporting heroes.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, bicycle racing as a sporting event reached feverish popularity both amongst the public and within artistic circles. In the early twentieth century racing developed as a distinct facet of modernity. The bicycle was the pre-eminent vehicle of the avant-garde.

Annie Londonderry

For women the bicycle was a “freedom machine” and a symbol of independence. It became a political force, an emblem of liberation. A popular line in the American press suggested that “woman is riding to suffrage on the bicycle.” Negotiating this new form of transportation was so liberating that women were eager to burn their bustle-cages. The bike not only forced a move away from the restrictive fashion of the Victorian age, for some women cycling was a life-changing exercise. Activists on bikes became role models in the emancipation process. Their pedals inspired social mobility.

A Jewish immigrant from Latvia, Annie Cohen Kopchovsky was a strong willed mother of three children under the age of six who took on the seemingly risible challenge to cycle around the world. Sponsored by the Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company of Nashua, New Hampshire, she was given the nickname Annie Londonderry. She started her epic journey on June 27, 1884, carrying with her only a change of clothes, a pistol, and her sponsor’s advertising placard.

Having reached the city of New York, she sailed to Le Havre from where she part cycled, part traveled by train to Marseille. The French public was intrigued, turning up in large numbers to encourage her. She then sailed to Alexandria, Colombo, Singapore, Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Nagasaki. In large towns and cities throughout the journey, Annie would halt and captivate audiences with colorful tales that were often exaggerated or completely made-up. She knew how to manipulate the media.

In March 1895 she landed in San Francisco, rode to Los Angeles, and then cycled through Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Nebraska. She arrived back in Boston fifteen months after leaving. She fulfilled what she had set out to do: to prove that women were equal to men in achieving what was considered the near impossible.

African-American Champion

Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor was born on November 26, 1878, in a rural area on the fringes of Indianapolis. His grandfather was enslaved in Kentucky; his father had been a Union soldier in the Civil War and, after moving from Kentucky to Indiana, was employed as a coachman in the family home of Albert Burley Southard, a railway executive who gave young Marshall his first bicycle.

Whilst in his early teens, Taylor’s agility caught the eye of the owners of the local Hay & Willits Bicycle Shop. They employed the youngster to perform stunts in front of the store. As he was dressed in a military uniform, his performances earned him the nickname “Major.” The tag would stick throughout his illustrious career.

Later Marshall worked as an instructor in a bicycle shop that was co-managed by Louis “Birdie” Munger, a retired racing cyclist who had started building bicycles in Indianapolis. He recognized young Marshall’s talent. Despite being barred from cycling clubs and the unwillingness of white cyclists to compete against an African-American, Marshall did participate in July 1895 in a seventy-five mile race from Massachusetts Avenue, Indianapolis, to Matthews in Grant County – and won.

In September that year Munger signed up his protégé to race at the Capital City Cycling Club’s track in Indianapolis (although it was whites-only event). He won over the crowd by setting new record-breaking times, but angry officials refused to acknowledge his efforts. Marshall was banned from further racing there. The taste of success however urged him to continue. Making his debut as a professional rider, he won the 1896 Six Day Bicycle Race at New York’s Madison Square Garden by clocking a record 1,732 miles on the track. He was the only African-American competitor.

Between 1896 and 1904 Major participated in races in Chicago, Connecticut, and New York. In spite of blatant and at times violent racism at the races, he would set world records at various distances between one-quarter mile and two-miles. In August 1899 he won the world championship in the one-mile race in Montreal, becoming the second African-American to win a sporting world championship (bantamweight boxer George Dixon had been the first in 1887).

Marshall’s talent was widely acknowledged in September 1900 when he won the American national championship in front of a crowd numbering more than 10,000 people. The press praised him as the “Black Cyclone,” but there was a cloud hanging over his career as he was denied opportunities to compete. White pros refused to race against an “intruder” which made it impossible for Taylor to complete the full round of the championship season.

European promoters in the meantime had been keen to offer Marshall a lucrative contract. In 1901, he crossed the Atlantic to take part in events that on several occasions had to be rescheduled for his sake. As a committed Baptist he refused to race on Sundays. In spite of that, between 1901 and 1904 Marshall defeated the best cyclists not just in Europe, but also in Australia and New Zealand, winning most of the races that he participated in, proving his reputation as a world-beater.

Parc des Princes

On June 4, 1972 President Georges Pompidou opened the Parc des Princes stadium with its innovative ring-shaped roof providing Paris with a state of the art venue for international rugby and soccer matches. The stadium replaced the velodrome of the same name that had stood in its place since July 1897 under directorship of former racing cyclist Henri Desgrange.

Nicknamed the “Father of French Cycling,” HD was also editor of the sports journal L’Auto (later: L’Équipe) which in 1903 initiated the Tour de France, to this day the world’s most spectacular cycling event. Every year until its destruction in 1967, a wild crowd at the Parc des Princes would welcome the arrival of those brave cyclists who had completed the brutal Big Loop (“La Grande Boucle”).

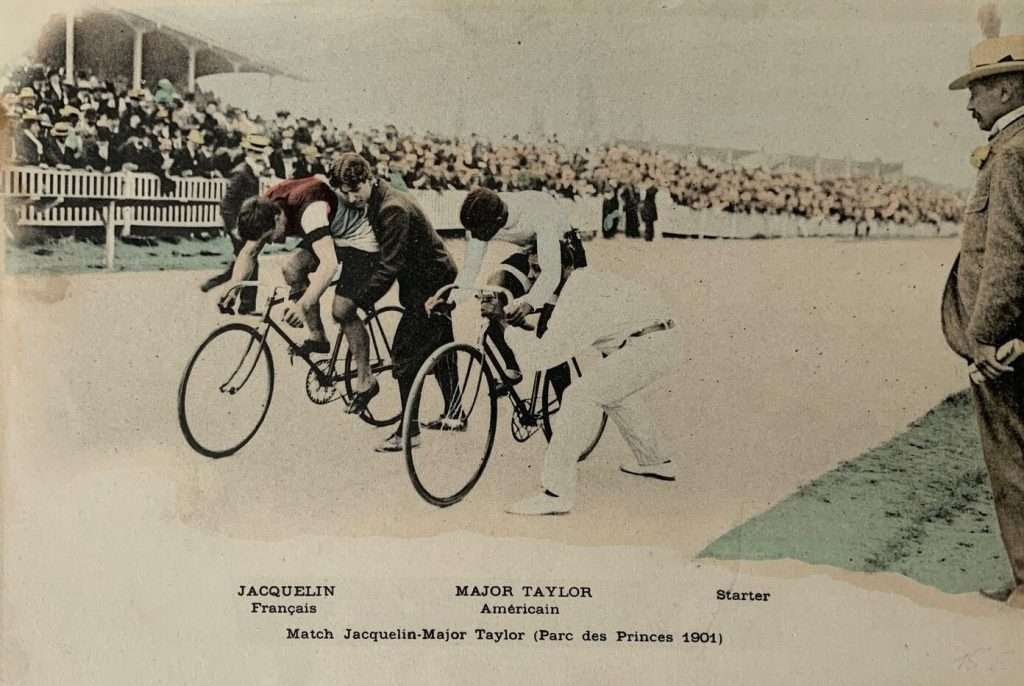

One of the highlights at the velodrome took place on May 16, 1901, when the reigning French sprint champion Edmond Jacquelin took on the American title-holder Marshall “Major” Taylor. Jacquelin had been absent when Marshall was hailed World Champion in Montreal (1899) and Taylor did not take part when Edmond was crowned World Champion in Paris (1900). It added spice to an eagerly anticipated encounter in which the two stars went head-to-head across the best of three heats.

The press had whipped up excitement, describing the event as an unofficial World Championship battle, featuring the master of Old Europe versus the star of the New World, a race in which a white Frenchman challenged a black American. The stands at the Parc des Princes were packed to capacity with some 20,000 spectators waiting in suspense. The duel turned out to be a disappointment. Jacquelin beat Taylor by two heats to nil, winning by a wheel in the first round and two lengths in the second. A re-match took place on May 27 with the Cyclone storming back to thump his opponent.

The sprinting head-to-head would become one of those sporting events that lived on in the public imagination. Endless pages of post-race analysis filled the cycling papers. Had the conditions changed? Had Taylor prepared himself better than his opponent? Was it all a sham in an attempt to set up a lucrative third and decisive meeting? To this day, sporting historians argue about the significance of a controversial encounter that in the end was never settled.

Modernism

Modern literature traveled on a bike. Alfred Jarry’s final novel Le Surmâle, roman moderne (1902) features a race between a train and a team of cyclists. The story concentrates on the exploits of a “super male” who is capable of prodigious muscular feats of endurance. Samuel Beckett’s works overflow with references to bicycles, including the extended “Dear bicycle” monologue in Molloy.

Early on Easter Sunday, 1897, a group of racing cyclists set out from Paris to Roubaix, an industrial town on the Belgian border. The 175 mile route ran along tracks of cobble stones that rattled the handlebars so badly it gave the riders nosebleeds (the contest was later dubbed “Hell of the North”).

One of the amateur participants was Maurice de Vlaminck, co-founder of the Fauvist movement. Although he did not finish the grueling race, cycling to him was an integral part of the creative process. Pedaling through the countryside of the Île-de-France he became “intoxicated with the light” that is such a vital part of his painting.

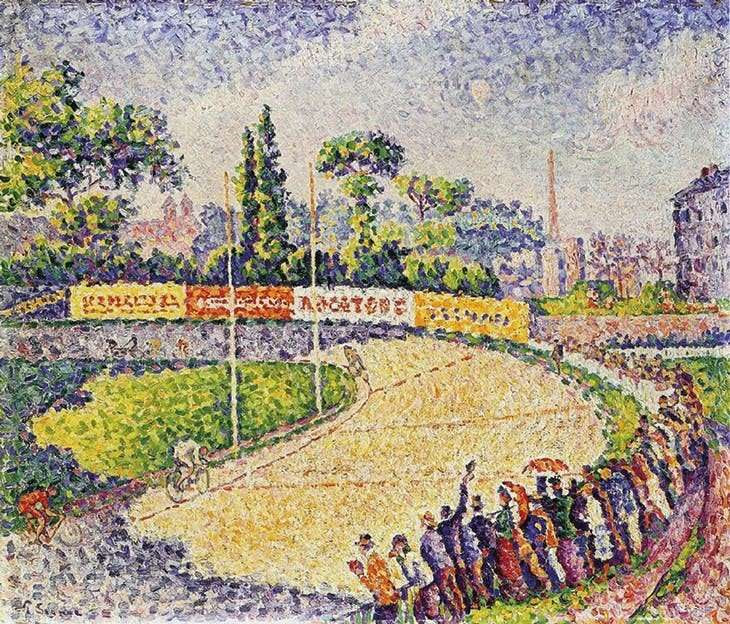

Within the context of European modernism, the bike figures strongly in art and design. Artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec (a great cycling fan) and Alphonse Mucha designed posters for bicycle manufacturers. Paul Signac’s pointillist painting Le Vélodrome dates from 1899. In 1908, Aristide Maillol was commissioned by Harry, Graf (Count) von Kessler, a great promotor of modernist art, to sculpt a statue of his young lover Gaston Colin. The bronze became known as “Le coureur cycliste,” the first known statue of a racing cyclist.

For artists of the Futurist movement the bicycle with its speed and turbine-like wheels was the embodiment of the machine age they exalted. Italian artistic interest in cycling goes back to Umberto Boccioni’s 1912/3 painting Dinamismo di un ciclista that demonstrated his preoccupation with the depiction of movement.

Natalia Goncharova and her partner Mikhail Larionov stood in the vanguard of modernist Russian painting. In March/April 1912, they organized the ground-breaking Donkey’s Tail exhibition in Moscow where Natalia exhibited her painting The cyclist (1913) in which the influence of Futurism is evident. In the two years preceding the First Word War, cycling had become a recurrent theme in art.

Feininger’s Cyclist

Major Taylor’s first bike race in Europe was held in April 1901at Berlin’s Friedenau velodrome. At that time, there was an American free-lance artist living and working in the city.

Lyonel Feininger was born Léonell Feininger on July 17, 1871, in New York, to the German-American composer Karl Feininger and his American wife. In 1887 he travelled to Germany to pursue a career in music, but decided instead to study drawing at Hamburg’s Kunstgewerbeschule. In 1888 he moved to Berlin where for four years he attended the Akademie der Künste and worked as a caricaturist for various American and German newspapers and sports magazines.

His output included a number of cycling-related cartoons. Cycling was his passion, riding the latest racing bikes available, though for his own pleasure rather than competitively. Feininger would not have missed Major’s appearance on the Friedenau track. In 1906/7 the artist was in Paris, mixed in avant-garde circles, and made the most of this cultural experience. There too Lyonel witnessed the intense excitement created by the presence of Major Taylor who set two new world records whilst racing in the capital. What is the relevance of all this?

In 1912 Feininger created his painting “Das Radrennen” (The Bicycle Race) which he submitted to Berlin’s First German Autumn Salon (Herbstsalon). Organized in 1913 by Herwarth Walden at his modernist Sturm Gallery, this was one of the first major Expressionist exhibitions that took place in Germany. Of all the works of art dedicated to bicycle racing at the time, Feininger’s image is unique in that it incorporates a black coureur.

Created two years after Taylor’s retirement in 1910, it may well be that at the time of creation the artist had the prestigious career of his compatriot in mind. Was it a belated tribute to the Black Cyclone?

At the peak of his career, Marshall “Major” Taylor was the fastest man on two wheels. Unfortunately, he did not leave a legacy. Racing remained and Illustrations: Annie Cohen Kopchovsky with her Londonderry-sponsored bike; Marshall “Major” Taylor (Smithsonian National Museum of American History); Postcard from May 1901 showing Major Taylor versus Edmond Jacquelin at Parc des Princes, Paris; Paul Signac, Le Vélodrome, 1899 (Private collection); Natalia Goncharova, The Cyclist, 1913 (State Russian Museum, St Petersburg); Lyonel Feininger, “Das Radrennen” (The Bicycle Race), 1912 (National Gallery of Art, Washington).still is an unbearably “white” sport. Cycling badly needs another Major.

Illustrations: Annie Cohen Kopchovsky with her Londonderry-spon

JUST PUBLISHED

CONTEMPORARY ART UNDERGROUND

Contemporary Art Underground presents more than 100 permanent projects completed between 2015 and 2023 by MTA Arts & Design. This ground-breaking program of site-specific projects by a broad spectrum of well-known and emerging contemporary artists has helped to create a sense of character and place at subway and commuter rail stations throughout the MTA system. Among the featured artists are Yayoi Kusama, Kiki Smith, Nick Cave, Ann Hamilton, Xenobia Bailey, Jim Hodges, Alex Katz, Sarah Sze, and Vik Muniz.

Of special interest is the discussion of fabricating and transposing the artist’s rendering or model into mosaic, glass, or metal, the materials that can survive in the transit environment. This is the definitive survey of the latest works of the internationally acclaimed MTA Arts & Design collection. On view 24 hours a day, the collection is seen by more than four million subway riders and commuters daily and has been hailed as ‘New York’s Underground Art Museum.’ The collection enlivens stations in all boroughs, with a myriad works by major contemporary artists executed in mosaic, glass, metal, and ceramic.

CREDITS

Hello there! Just a quick note to let you know that all material is the property of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society, © 2020, rights reserved. Big shout-out to New York Almanack and Judith Berdy, who make our work possible. Stay in touch with us via email at rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com and don’t forget to check out our website www.rihs.us for more information. If you ever want to update your subscription preferences or opt out of our mailing list, we’ve got you covered!

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

www.tiktok.com/@rooseveltislandhsociety

Instagram roosevelt_island_history

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment