Monday, July 8, 2024 – A BRITISH TRADITION CONTINUED IN BROOKLYN

LITTLE STAFFORSHIRE;

POTTERY &

CHAIN MIGRATION

MONDAY, JULY 8, 2024

NEW YORK ALMANACK

ISSUE # 1267

Brooklyn’s Little Staffordshire: Pottery & Chain Migration

July 6, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp

The village of Red Hook (Roode Hoek = Red Corner) was established by Dutch colonists in 1636 and named after the locality’s red clay soil. Two decades later its community became part of Brooklyn.

During the 1650s, settlers brought over ovens from the Low Countries to supply fellow colonists with household vessels. Manhattan’s production of red earthenware is thought to have begun with Dirck Claesen, a potter based in the New Amsterdam settlement.

Born in Leeuwarden, Friesland, he had arrived in New Netherland in 1653. As early products resembled objects produced at home, it is difficult to differentiate between local products and imports.

The expansion of the city of New York after the Revolution boosted the need for household earthenware and helped sustain local potters. Their numbers increased once mass migration from Europe was set in motion. Amongst the newcomers were many English potters who settled in Brooklyn and revitalized the industry.

The Six Towns

The “Potteries” is a collective name for six towns in Staffordshire (Stoke-on-Trent, Longton, Fenton, Hanley, Burslem and Tunstall) where during the Industrial Revolution the ceramic industry boomed. The availability of clay, coal and clean water from the River Trent meant that manufacturers had ready access to vital resources.

In 1770, Josiah Spode was the first Staffordshire potter to develop a viable method of manufacturing blue and white ceramics. His son Josiah II worked out the formula for bone china. Having opened a showroom in London in 1778, porcelain became popular amongst the city’s wealthy elite.

Although preceded by Josiah Wedgwood, Spode’s enterprise set a standard that was followed by the likes of Minton, Copeland and Ridgeway. Railway expansion in the 1840s increased distribution and soon there were over two hundred “potbanks” in operation, employing some 50,000 people.

With growing demand at home and abroad, manufacturers built larger ovens with little consideration for their workers. Factories were divided into workshops where skilled laborers were paid on “piece-rates,” their earnings depending on the number of pots produced. Child labor was common.

The kilns created a permanent haze of black smoke and turned the six towns into a polluted wasteland. Poor conditions caused ill health. Silicosis or “potter’s rot” was a common disease.

By 1824, potters had gained the right to organize into unions and negotiate conditions of employment. Forward steps were made, but by the mid-1830s the relationship between employers and workers worsened.

In 1836 the National Union of Operative Potters called out a strike that lasted for twenty weeks until starvation forced members to return to work. The walkout was followed by a recession in the early 1840s. Unemployment rose sharply and factory owners invested in machinery to reduce the wage bill. Skilled workers competed with each other for a diminishing number of jobs at low wages.

In 1843 a new union of potters was founded which, instead of confrontation, suggested a scheme to reduce surplus labor and improve the bargaining position of remaining workers.

The union supported emigration to the colonies. In April 1845 a polemical poem entitled “The Pioneers Song” appeared in the weekly newspaper The Potters’ Examiner, published in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, calling for English potters to forsake the tyranny of their employers and move to America.

The final verse reads:

But away with the pain – we shall see them again!

We are only preparing a way for the rest:

Then blow! Breezes blow! As onward we go-

The Potters shall yet have a home in the West!

Ceramics may not have figured on a priority list of crafts in America at the time, but urbanization and the push westward had increased consumer demand. The discovery of raw material deposits opened up the potential of a viable industry. The 1840s saw a sustained period of potter migration from the Potteries to the United States.

Beauties of America

Prior to the Revolutionary War, colonists imported mass produced earthenware from English potteries. In spite of trade interruptions the pattern was continued after independence. Entrepreneurs at Staffordshire factories promoted patterns that would appeal to American patriots. White items of pottery were decorated with transfer-printed scenes of New York and other cities, portraits of the Founding Fathers and coats of arms from the new states.

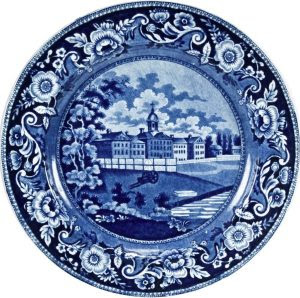

In September 1822, Hanley potter John Ridgway sailed to Boston, Massachusetts, where he began a two-month tour in order to procure American prints and views and establish relationships with local ceramic merchants. On his return he began the process of creating his “Beauties of America” dinner service by transferring twenty-two views and landscapes onto plates, dishes, gravy boats, etc.

Burslem-born Andrew Stevenson ran the Cobridge Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent. An enterprising character he set out to seek a market niche in New York City. In January 1823, he sailed on the packet ship James Cropper from Liverpool with a consignment of earthenware. Later that year, Spooner’s Brooklyn Village Directory listed Stevenson as a “China & earthenware Manufacturer / Address Mansion House, Brooklyn Heights / Store 58, Broadway, New York.”

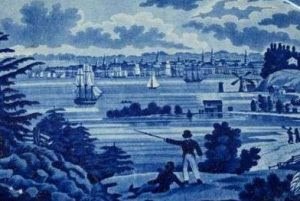

The business did not last long. In November 1823, the New York Gazette and General Advertiser supplied details of a sale at the above address of an assortment of china, earthenware and glass. From Brooklyn Heights Stevenson had enjoyed a view of the city which, on his return to Cobridge, served as inspiration for printed patterns on plates and dishes – New York in Staffordshire blue.

Greenpoint

Located at Brooklyn’s northernmost point, Greenpoint was an industrial site that would become associated with shipbuilding, but the first firms here were practitioners of the so-called “five black arts.” Glass and pottery makers, printers, refiners and cast-iron producers were so named because of the toxic fumes they produced. Smokestacks were a feature of Brooklyn’s skyline.

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, there were at least a dozen potteries operating here. Many of the entrepreneurs and workers were English-born. This was a case of chain migration, the socio-economic process by which migrants from a particular place follow others from that area to a specific destination. Greenpoint was turned into Little Staffordshire.

Although modellers brought along popular English styles and motifs (such as Toby jugs), they quickly incorporated local flowers, trees, fish and animals in their pottery designs. Niagara Falls inspired waterfall scenes. In addition to utilitarian pieces, they began to produce “Fancy” ceramic pieces in a variety of styles, glazes and materials.

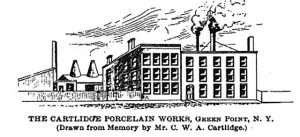

In 1848, a migrant by the name of Charles Cartlidge set up a works in Freeman Street. Born in 1800 into a Burselm family of potters, he manufactured tea sets, pitchers, bowls, door knobs, buttons, cane heads, inkstands and cameos. His brother-in-law Josiah Jones modeled “busts of celebrated Americans” in what the firm always described as bisque (white unglazed) porcelain.

Cartlidge engaged talented painters to decorate the firm’s products. One of these artists was Elijah Tatler who had served an apprenticeship at Minton in Staffordshire. After Cartlidge closed the factory in 1855, he would establish his a decorating business in Trenton, New Jersey.

In 1853 Longton-born William Young, also a former employee at Cartlidge, settled in Trenton producing decorative hardware and household crockery. During the 1860s, several potteries were ranged along the Delaware and Raritan Canal.

Two years after closure of Cartlidge’s pioneering firm, German-born William Boch founded a pottery in Greenpoint. He produced Rococo-style pitchers as well as household ceramics and ornamental figures. Boch displayed his wares at Manhattan’s spectacular Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1853. But, as with Cartlidge, the firm ran into financial difficulties and passed into the care of a stock company. At the outbreak of the Civil War, a new owner took over.

Patriotic Pottery

Thomas Carll Smith had started his career in New York as a builder. A wealthy man at a young age, he had funds to invest. Although without experience in pottery and in spite of the high rate of failure in the trade, Smith decided to proceed.

In 1863, suffering from ill health, he traveled to Europe to recuperate and embraced the opportunity to visit the French porcelain factory of Sevres and some potteries in Staffordshire. He engrossed himself in the minute details of porcelain making.

On his return he renovated the factory which he named the Union Porcelain Works (UPW) and invested in the plant’s modernization. He acquired a quarry in Brachville, Connecticut, to secure the supply quartz and feldspar. Located at 300 Eckford Street, UPW became the main manufacturer of porcelain tile, door knobs and fireplace ceramics, a position it held well into the 1920s when the factory was finally closed.

But Smith had bigger dreams. His ambition was to compete with the quality china of Limoges or Meissen. Unwilling to copy European motifs, he resolved to use only original designs and create typical American patterns.

In 1874 he offered a job to sculptor Karl Müller to design wares for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Born in Germany about 1820 and trained in Paris, Müller had moved to the city of New York in the aftermath of the 1848 political unrest. Smith admired his work.

Müller’s designs at the Exhibition attracted keen interest. His most notable contribution was a pair of large Century Vases, each covered with a profusion of historical and patriotic scenes. Bison heads serve as handles; a portrait of George Washington embellishes each side; and six biscuit-relief panels around the base depict historical events.

By producing uniquely themed china, UPW shaped a stylistic tradition that set the tone for future developments. The 1876 Centennial spurred on a vogue of collecting Americana. People sought out items memorizing the early years of the Republic, from furniture and silver to ceramics with patriotic themes.

Pioneering Pottery

Decorators were elite artisans in porcelain manufacturing as the work required both artistic talent and the skill to paint with enamels. Born in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Edward Lycett was apprenticed aged twelve at Copeland & Garrett, the former Spode manufactory in Stoke-on-Trent.

In 1852, he joined Thomas Battam’s renowned decorating firm in London. He created classical figures and cameo medallions as well as flowers, birds and fish in a palette that was characteristic of the finest china painting in England.

Lycett was one of many Staffordshire craftsmen who made his way to New York in search of new challenges and better prospects. He settled in Greenpoint in 1861 where he worked to order, sometimes alone and on other occasions in partnership, decorating a range of wares in a variety of styles, from ornate dinner services to bar pitchers, building a growing name for himself. In 1866 he was commissioned by President Andrew Johnson to paint a china set for use in the White House. His reputation rocketed.

In 1884, eager to experiment with the aesthetics of design, he accepted an invitation by Bernard Veit, part owner of the Faience Manufacturing Company, to take up the role of Art Director. French faience (tin-glazed earthenware) and Limoges wares had been fashionable ever since the Centennial Exposition.

It inspired the name of the company and served as models for wares produced at the Brooklyn factory and sold at Veit & Nelson’s showrooms in Lower Manhattan. But the public’s taste was changing, becoming more focused on Royal Worcester or Crown Derby porcelain. Lycett was appointed to facilitate the change towards the creation of art pottery.

Within two years of his arrival, he transformed the Faience Manufacturing Company’s artistic agenda. Edward specialized in large bulbous vases and ewers decorated with an eclectic mix of Japanese and Islamic influences that reflected the “cult of beauty” associated with the Aesthetic Movement.

Imposing size and complex in decoration, his designs of the 1880s exhibited an American inspiration that distinguished them from those by European art potteries. They were sold in elite art emporiums, including Tiffany & Company. He set a new standard of excellence in ceramics.

The high cost of producing labor-intensive art ceramics for a relatively small market was not sustainable. In 1890, the Faience Manufacturing Company ceased production. Lycett retired, but his legacy endured.

In 1895 historian Edwin Atlee Barber (author of Marks of American Potters in 1904) described him as “The Pioneer of China Painting in America” and the label stuck. He stood out as a gifted craftsman in Brooklyn’s Little Staffordshire community.

2006

BRAND NEW BUS #3

Judith Berdy

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

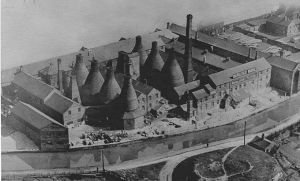

Illustrations, from above: A detail from Andrew Stevenson’s platter “New York from Heights near Brooklyn,” a Staffordshire blue roast dish from ca. 1825 (Brooklyn Museum); Middleport in the Potteries, Staffordshire, from above; 20th century workers in the casting room Middleport pottery, England; Andrew Stevenson’s plate showing the 1816 Alms House in New York City on the banks of the East River; the Cartlidge Porcelain Works at Greenpoint, “drawn from memory by Mr. C.W. A. Cartlidge”; a William Boch pitcher decorated by F.K.M. Kropp, 1850s (Brooklyn Museum); a Karl Müller vase, ca. 1876 (Brooklyn Museum); and a Edward Lycett covered vase, ca. 1887 (University of Richmond Museums).

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment