Thursday, July 25, 2024 – THE BUILDING THAT MAKES MUSIC HISTORY

MANHATTAN’S BRILL BUILDING

&

AMERICAN POP MUSIC HISTORY

NEW YORK ALMANAC

ISSUE #1279

THURSDAY, JULY 25, 2024

Manhattan’s Brill Building & American Pop Music History

July 24, 2024 by Guest Contributor

During the 1960s, the Brill Building in Manhattan revolutionized all aspects of the music industry. The operations of this one building turned the fledgling genres of rock and pop into a streamlined machine.

In a matter of a few years, the building’s music businesses revolutionized the process of songwriting, recording, and promotion. On top of this, the building produced timeless hits of the 1960s and launched the careers of the biggest singer-songwriters in history.

So how is it that a rather unassuming building in the heart of Manhattan could have such an immense impact?

The origin of the Brill Building can be traced back to one man: Abraham Lefcourt. Lefcourt was born in Birmingham, England in 1876 but immigrated to Manhattan in 1882.

He worked his way up through the ranks of New York City society, starting work as a shoeshine and newsboy. Lefcourt’s break came when he made his foray into the world of real estate.

In 1910, he built a 12-story building housing garment businesses. By 1930, he had developed 31 multi-million dollar properties throughout Manhattan’s Garment District.

In 1929, Lefcourt turned his attention to a property on the corner of Broadway and 49th Street. This property housed the Brill Brother’s men’s clothing store, but Lefcourt had greater ambitions for it. He aspired to build the tallest building on Earth – a 1,050 foot skyscraper – on the site of the store.

Lefcourt soon leased the property from the Brills and began construction on his $30 million colossus.

This plan was far from unique to Lefcourt. During the 1920s, Manhattan moved upward, with firms competing against one another to build the tallest tower in the city. The years following the First World War saw the US population and economy boom, leading to a need for 10 times more office space than was available.

On an island as small as Manhattan, the only choice was to build upward. As architect Louis Horowitz remembered, “Our bellwether was proven by the sudden hurry of many to lease offices from us-inland manufacturers of everything that fighting soldiers needed. Brokers, lawyers and a host of others signed up for space.”

In line with this was a trend of growing consumerism. More and more people could afford automobiles, radios, and tickets to movies – both silent and sound. In this period of unparalleled growth and prosperity, architectural projects likewise expanded, mirroring this growth.

As soon as there was demand for skyscrapers, there was also competition. By 1930, three Manhattan buildings were vying to be tallest in the world. The first completed was the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building at 40 Wall Street. With its upper pyramid reaching a staggering 927 feet, the building was the largest on record upon its completion in May 1930.

The building however would not keep this title for even a year before the Chrysler Building topped it at 1,046 feet. As the legend goes, Chrysler waited for the completion of 40 Wall Street, before raising the Chrysler Building’s trademark spire, giving it the title.

Again, within only a year, both towers had been dwarfed by the massive 1,454-foot Empire State Building. In spite of this, Abraham Lefcourt thought that his Brill Building stood a real chance at winning this architectural space race.

As if the space constraints were not bad enough, the market crashed one month into construction. October 29th, 1929 – known as Black Tuesday – ravaged Wall Street, and kicked off the multi-year Great Depression.

By 1932, the US stock market had lost 89% of its value, and unemployment rose to 25% as banks collapsed across the country. Lefcourt surprisingly viewed this as a blessing in disguise. He hoped that investors would abandon the stock market, and invest more in land, only emboldening his construction plans.

It was clear that construction constraints and the collapse of the global economy could not stop Lefcourt. However, personal tragedy in 1930 ended his architectural aspirations.

On February 3rd, Lefcourt’s son Alan died of anemia, and within one month Abraham had stopped construction of the building at only ten stories. Abraham christened this new office building the Alan E. Lefcourt Building in honor of his late son.

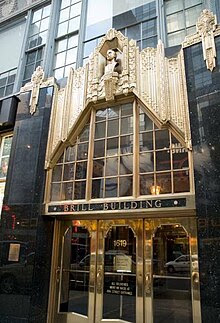

While nowhere near as tall as its competitors, the Lefcourt building was an architectural marvel in its own right. The white brick tower embodied the Art Deco style of the 1920s standing in stark contrast to the other buildings on Broadway. In addition, it features ornate terracotta reliefs, and brass portrait busts of Alan Lefcourt.

When the building opened in 1930, it hosted modern amenities that made it desirable as an executive office space. Upon its opening, the New York Times reported that it boasted “new automatic-stop, high-speed elevators,” and a shopping lobby.

Lefcourt began by leasing out entire floors to firms which were to be later subdivided. While some law and accounting firms, as well as utility offices opened, this model was largely a failure. By 1934, many offices were still vacant, leading to a shift in strategy.

Floors were divided up into small office spaces that were individually leased to tenants. This proved to be a success, attracting specifically the music industry to the building. Within only ten years, 100 music tenants had moved into the Brill Building.

The Origins of Popular Music in New York

The music industry within the Brill Building built off of a longer tradition of pop music in Manhattan. Since 1890, Midtown Manhattan had housed its own music industry known as Tin Pan Alley.

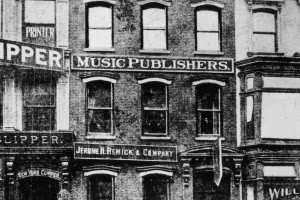

The area along West 28th Street originally housed residential row houses, but shifted towards music with the establishment of M. Witmark and Sons publishing in 1893. By 1900, the block had the largest concentration of music publishers anywhere in the country.

On top of this, Tin Pan Alley housed a large concentration of saloons and music halls that worked alongside publishers.

In many ways, Tin Pan Alley invented modern music promotion through the process of “plugging.” Plugging was the idea of having as many people as possible hear your song. In an era before radio, TV, or film, plugging required live performance.

As a result, Tin Pan Alley publishers allied with local music halls to promote their compositions. These promotions included free sheet music, singalongs, and other events. Because of these plugging techniques, Tin Pan Alley was always alive with the sound of piano tunes. This lively atmosphere gave the area and industry its name, with “tin pan” being slang for the cheap pianos used in the area’s saloons.

Throughout its operations, Tin Pan Alley launched timeless hits and legendary careers. The Alley’s composers penned songs including “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” “God Bless America,” and “Hello Ma Baby.” Many of these Tin Pan Alley hits transcend era and genre, remaining well known almost a century after their composition. In addition to hits like these, many of the alley’s composers became celebrities in their own right.

One such composer was a young Russian immigrant named Israel Beilin, who immigrated to Manhattan in 1893. Upon his naturalization, immigration authorities legally changed his name to Irving Berlin.

At only 19, Berlin was composing songs for Tin Pan Alley publishers. With hits like “Alexander’s Jug Band,” and the aforementioned “God Bless America,” Berlin took over popular music. Throughout his career, he penned hundreds of songs, and topped the charts 25 times.

Tin Pan Alley publishers also revolutionized the music industry through the creation of dance crazes. capitalizing off past theater and ragtime hits, the alley’s composers began writing danceable novelty songs. These – like modern dance crazes – were meant to be fads, spreading quickly and aiding in the sale of sheet music to clubs across the country.

Many of these Tin Pan Alley dances were just that, with the “Turkey Trot,” “Grizzly Bear,” and “Cubanola Glide” quickly gaining popularity then falling out of favor. One dance – The Foxtrot – became a craze unlike any other, growing into its own genre.

These dance crazes foreshadow a technique that Brill Building songwriters would latch onto decades later. In fact, Brill Building writer Neil Sedaka argues that its songwriting infrastructure was a natural evolution of Tin Pan Alley plugging.

Despite its massive success and revolutionary methods, Tin Pan Alley did not last forever. For one, the local industry could not keep up with the technological advances of the 1920s.

Much of Tin Pan Alley’s profits were directly tied to the sale of sheet music, which quickly became outdated as radio and recordings were becoming more widespread. Despite this, many publishers were able to persevere despite lowered sales.

The invention of the sound movie – or “Talkie” – was what really ended the alley’s operations. The medium was a great vehicle for song promotion, leading to West Coast entertainment firms buying up many of the local publishers in the alley.

As Tin Pan Alley was dying down, a new genre called Jazz was exploding in Manhattan. During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, New York became a hub for African American musicians and artists. Jazz was not a new genre, with its roots originating from the musical tradition of America’s enslaved population.

As the New York Times reported in 1926, “Jazz came to America 300 years ago in chains.” Despite this long history, the 1920s was when jazz really emerged onto the music scene.

In Harlem’s speakeasies, like the Cotton Club, artists like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong revolutionized the genre and introduced it to larger and larger audiences. As a result of these artists, the 1920s is often remembered as the “Jazz Age.”

As the US entered the 1930s, many Jazz artists began incorporating elements of Tin Pan Alley songs. Jazz bands were growing in size, featuring large horn and rhythm sections. Bandleaders began performing slower, lushly orchestrated jazz versions of the foxtrot.

This type of swing music became known as “Big Band” due to the size of the ensembles performing it. Big Band soon became the defining sound of the era, with bandleaders like Count Basie, Benny Goodman, and Bob Crosby topping the charts.

The Brill Building Becomes a Music Hub

When Tin Pan Alley’s influence began to wane, many of its songwriters still remained in New York. Needing work, many publishers, songwriters, and promoters began to lease small offices in the Brill Building throughout the 1930s. Stars of the Harlem Renaissance like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington, as well as big band stars Louis Prima and Nat King Cole all had offices in the building during the decade.

In addition to these big names, songwriters continued their work in the building, adapting the process of plugging for the radio era. These composers would take songs written in the Brill Building and present them to radio stations and orchestras to be made into hits.

Brill Building songs were frequent features on Billboard’s Hit Parade radio program, with stars like the Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and Tommy Dorsey Orchestras performing them. The building’s operations during the Big Band Era established the framework that its songwriters perfected during the rock n roll age.

By the 1950s, Big Band and crooners were falling out of fashion with American teens, who were becoming enthralled by rock ‘n’ roll. Much like its predecessor jazz, rock originated from the musical tradition of enslaved African Americans in the South.

This musical tradition, encompassing blues, country, and gospel slowly melded together to form something entirely new. Building off of guitar virtuosos like Robert Johnson, bluesmen like T Bone Walker and Muddy Waters began to incorporate electric instrumentation into their stylings.

These bluesmen established the electric guitar as the centerpiece of the genre, establishing the foundation for rock ‘n’ roll. In 1951, Jackie Brenston released “Rocket 88,” often considered to be the first rock record. The song is heavily indebted to the blues, being led by piano and saxophone with an underlying distorted guitar.

The song hit #1 on the Billboard R&B charts, kicking off the rock era. By 1958, with the release of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” rock had become the genre of American youth. Piggybacking off of this success, radio programs, jukeboxes, and American Bandstand all highlighted rock music.

It was this explosion of rock ‘n’ roll into the American mainstream that truly made the Brill Building. By the end of the 1950s, songwriters played a major role in rock music, penning tunes for rock stars to perform.

Perhaps the most influential songwriters were the duo of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who wrote Elvis hits “Hound Dog,” and “Jailhouse Rock.” With songwriters like these, there was a “professionalization” of the rock genre, with a streamlining of the songwriting, recording, and promotion processes.

The Brill Building quickly became the center of this professionalized rock industry. By 1962, the Brill Building housed 162 music businesses.

In 1958, publishing duo Don Kirshner and Al Nevis founded Aldon Music, which quickly became the city’s paramount music business. The firm was originally located at 1650 Broadway – a block away from the Brill Building – but cooperated closely with the building’s businesses.

Kirshner and Neivis recognized the importance of marketing towards America’s teens, and created an assembly line for rock music production. Aldon Music realized that teen songwriters could best understand the sensibilities that would appeal to the youth market. As a result they established a team of young writers to crank out pop songs.

This songwriting process was ruthlessly efficient. Writers would work in small offices, often adorned with only an upright piano, penning teen pop songs for hours each day. Once finished, writers would take their songs to the building’s publishers until someone bought them.

On top of that, publishers could get arrangements, vocalists, and lead sheets all from within the building’s businesses. With all of those pieces, a demo could be recorded all within the same day.

In many ways, the Brill Building was its own self-contained industry, containing all the ingredients needed for pop song writing, recording, and publishing.

You can read more about the Brill Building’s role in creating modern pop music at our arts and culture reporting partner NYS Music.

CREDITS

NYS Music is New York State’s Music News Source, offering daily music reviews, news, interviews, video, exclusive premieres and the latest on events throughout New York State and surrounding areas. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

Illustrations, from above: Tin Pan Alley in 1905; Abraham Lefcourt, June 1927 (courtesy Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University); The Brill Building in 1931; The Brass Portrait bust of Alan E. Lefcourt above the Brill Building’s entrance; and a young Paul Simon and Carole King in the Brill Building, 1959.

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment