Monday-Tuesday, August 5-6, 2024 – THINKING OF GREAT DINING….MAYBE IT IS THE PARIS OLYMPICS

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY-TUESDAY, AUG. 5-6, 2024

WAITERS, RESTAURERS,

AUTOMATS &

DEPRESSION COCKTAILS

Jaap Harskamp

New York Almanack

Waiters, Restaurers, Automats & Depression Cocktails

August 5, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp

An automaton is a machine designed to operate on its own by responding to predetermined instructions. By the mid-eighteenth century, a number of talented craftsmen operated in Paris from

where they exported clockwork automata and mechanical singing birds around Europe and beyond.

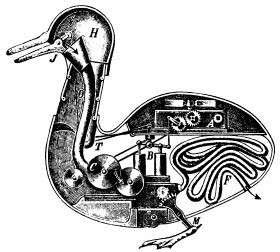

The undisputed master in this domain was Jacques de Vaucanson. In 1735, he constructed a life-sized flautist that produced twelve melodies. His masterpiece was unveiled in May 1764 when he presented a “Canard Digérateur” (Digesting Duck) to the public.

The bird consisted of a copper exterior with more than a thousand moving parts. As well as flapping its wings and quacking, it appeared (by a design trick) to have the ability to eat kernels of grain, then digest and defecate them.

De Vaucanson was a man of the Enlightenment. He combined his studies in anatomy at the Paris medical school with an interest in mechanical inventions. Like the philosophers of his day, he was intrigued by the “man and machine” issue.

In 1747, Julien Offray de La Mettrie published L’homme machine (Man: A Machine) in which argued that all living beings are machines fueled by food. The human body is the “living image of perpetual movement.” He proposed the slogan: “You are what you eat.” Linking mechanical technology with food consumption would later acquire a specific relevance.

Are You Being Served?

The Enlightenment marked a turning point in the history of cookery. As gluttony gave way to refinement, settings were improved. Tables were laid with crockery; cutlery and (crystal) glasses became part of the ritual. Round tables inspired convivial interaction. Consumption was associated with well-being.

Throughout his work, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (a vegetarian) discussed food, suggesting that a nutritious “natural” diet would boost the formation of a wholesome character. The word restaurant itself was derived from the verb restaurer (to reconstitute). Early Parisian restaurants reflected the health awareness of the era. These establishments focused on selling a slow cooked bone broth (bouillon) as their main dish.

One of the first restaurant proprietors was A. Boulanger, a “bouillon seller,” who opened his business near the Louvre in 1765. In his establishment, soups were served that had the reputation

of restoring strength to those who suffered poor health. Its sign bore the motto: “Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis et ego restaurabo vos” (Come to me, all of you whose stomachs hurt and I will restore you). The proprietor called himself a healer or “restaurateur.”

Boulanger was not content to serve just bouillon. He also offered leg of lamb in white sauce to his clients. As his action infringed on the monopoly of the powerful caterers’ guild, he was taken to court. The case ended in a judgment favoring Boulanger, thus lifting all restrictions on eating establishments.

Bouillon restaurants started to expand their offering and the popularity of eating out began to spread. In 1782 chef and culinary writer Antoine Beauvilliers opened La Grande Taverne de

Londres on the Rue de Richelieu in Paris. It was dubbed Europe’s first luxury restaurant.

The French Revolution accelerated the development towards the democratization of dining. The political events of the 1790s released kitchen staff from aristocratic patronage. As the nobles fled or faced the guillotine, their private chefs found themselves unemployed. They had to offer their skills to the public at large, setting up as independent restaurateurs catering to a new bourgeois clientele. By 1804 Paris had more than five hundred restaurants.

The word waiter in the sense of a “servant who waits at household tables” dates from late fifteenth century. In reference to inns and taverns it dates from 1660s, predominantly referring to someone who serves drinks. The proliferation of hotels and restaurants caused a transfer of workers in domestic service to the hospitality sector and contributed to the emergence of serving staff as a distinctive (hierarchical) occupational group.

Automat

From the outset, there has been an uneasy relationship between restaurateurs, waiters and clients. For owners, waiters were an expensive and often troublesome addition to the cost of running a business. For clients, their intrusive hovering around the dinner table was a source of continuous irritation.

Tipping was another disturbing issue. As small acts of generosity, tips had their origins in domestic service. Ever since the Tudor era, visitors to private homes would give sums of money (known as “vails”) at the end of their stay for service rendered by the host’s staff. Tips supplemented the wages of domestic servants.

The giving of vails was probably a uniquely British phenomenon and it is not known how the habit spread to restaurants and hotels. In hospitality, the expectation grew that the customer would subsidize the worker’s income (allowing employers to refrain from paying serving staff a fixed wage).

Towards the end of the nineteenth century the idea of the automaton re-emerged and was given a new direction. Researchers began to explore ways of developing a “waiter-less” system of service in order to improve efficiency, raise client satisfaction and reduce staff numbers.

The concept of an automatic restaurant was proposed in Germany. The word “automat” was introduced to describe any type of coin-operated dispensing apparatus.

The world’s first such restaurant was established in June 1895 on the grounds of Berlin’s zoological garden by a company named Quisisana that manufactured automat machines and equipment. On the first Sunday of operation it sold 5,400 sandwiches, 22,000 cups of coffee and 9,000 glasses of wine and cordials.

The firm’s name maintained the “healing” connotation of the term restaurant as it is derived from the Italian phrase “qui si sana” (here you become healthy).

In 1896 a new firm named “Automat” was founded as a joint venture between the Berlin engineer Max Sielaff, an inventor of different types of slot machines, and the Cologne-based chocolate maker Stollwerck. The company presented itself to the public at the Berlin Industrial Exposition that same year and was an instant hit.

Its “waiter-less” restaurant was designed by Sielaff and provided hot meals, sandwiches and drinks in a lavish dining room with stylish stained glass windows.

How did the Automat function? The walls of the establishment were lined with small windows, each of which contained edibles or drinkables. Customers inserted a coin to unlock the window, allowing them to pull out a meal or drink. The food came ready-made. No waiters. No tips.

The fame of automatic restaurants spread rapidly after one such premises won a gold medal at the Brussels World Fair of 1897. The German prototype was sold all over Europe and would soon reach the United States.

A Toxic Profession

Delmonico’s opened its doors in 1837, comprising lavish private dining suites and an enormous wine cellar. The restaurant, which still remains housed at its original Manhattan location, is said to be the first in America to use tablecloths. Delmonico’s employed an army of waiters.

With the rapid expansion of the hospitality sector, resentment against waiters increased. An 1885 editorial in The New York Times condemned servers as one of the “necessary evils of an advanced civilization.” Waiters were accused of rude mannerisms. A particular driver of anti-waiter sentiments was the expectation of tipping. The practice was despised as a European import and maligned as “offensively un-American.” Waiters were a strain, the prospect of having to tip them was an insult.

Affluent citizens were accused of having initiated the custom at resorts such as Saratoga Springs or Newport, guaranteeing good treatment for the stay. The word “tip” was British English (many critics blamed England for the practice), Americans tended to use the term “fee” which inspired a popular quip in the 1870s, “When you have feed the waiter of the summer resort, then he will feed you.” Attempts to eradicate tipping failed. Instead, entrepreneurs took an interest in European experiments with waiter- less restaurants.

Frank Hardart was an immigrant from Sondenheim, Bavaria, who had settled in Philadelphia working in hospitality. In 1888 he responded to an advertisement placed by Joseph Horn who was seeking a business partner. Horn & Hardart (H & H) founded a chain of establishments that catered to urban workers with a reputation for fast food and fresh coffee. Public esteem encouraged their willingness to experiment.

In 1901, Hardart traveled to Berlin and having seen the Automat technology in operation, the entrepreneurs shipped the machinery to America and opened a restaurant on June 12, 1902, at 818

Chestnut Street, Philadelphia. The first H & H Automat Lunch Room in New York City was established a decade later (July 1912) on Times Square to feed Broadway’s theatre crowd. A second

Manhattan location opened its doors shortly after on Broadway and East 14th Street.

Those who entered the premises were stunned by an impressive vending machine with rows of windowed compartments containing different menu items, including sandwiches, macaroni cheese, chicken pot pie, baked beans or coconut cream pie. Having made a choice, the customer dropped a nickel into a coin slot, turned a knob, lifted up the door and removed the food.

Unlike Manhattan’s sophisticated dining rooms, Automats were simple and democratic. But they were not without decorum. Many H & H premises were Art Deco designs with elegant marble counters and floors, stained glass, chrome fixtures and carved ceilings. Food was served on china plates and consumed with proper cutlery. French-drip style coffee was always hot and freshly brewed.

Just before the outbreak of the Second World War, at the height of the Automat’s popularity, the company had over eighty locations in Philadelphia and New York City, serving some 350,000 customers per day. In the second half of the twentieth century, Automats began to lose their prominent position with the emergence of more convenient fast-food restaurants. The last H & H Automat closed in 1991.

Depression Cocktail

H & H restaurants were integral to Manhattan’s cityscape. The Automat was an institution, a metaphor for a lifestyle in the spirit of the Ford assembly line. The “nickel-in-the-slot eating place” became an American icon (in spite of its European roots), celebrated on stage and screen. Movie stars like Audrey Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart, Gene Kelly and Gregory Peck all dined there. In Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Marilyn Monroe in the role of Lorelei Lee sang “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” (Verse 1):

A kiss may be grand but it won’t pay the rental

On your humble flat or help you at the automat.

Although Automats originated as a high-tech form of food service, they reflected New York City’s fast-paced and multi-national society where people from all walks of life gathered briefly to eat without being bothered by waiters before hurrying on with their day to day business. Smart but impersonal, H&H was a place of autonomy and instant gratification.

During the Great Depression, Automats offered cheap sustenance or a warm coffee to many impoverished people. They also offered shelter. The absence of waiters meant that homeless or unemployed New Yorkers could come in from the cold (or heat) without being requested to leave the premises. Some of them consumed a “Depression Cocktail” consisting of free ketchup mixed into a glass of water. The Automat could be a place of loneliness and lingering.

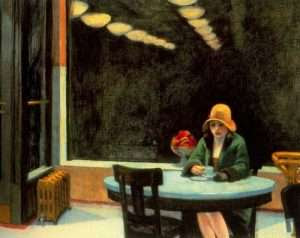

In 1927, there were fifteen Automats in New York City. On Valentine’s Day that year Edward Hopper opened his second solo show at the Rehn Galleries on Fifth Avenue. It was here that he first displayed his painting “Automat.” Like in other works, forlornness is the central subject of this painting.

In an evocative scene of introspection, it depicts a woman at a restaurant table staring downward over a cup of coffee on a seemingly cold night. The reflection of artificial light in the window glass highlights her melancholic solitude.

The sparsely furnished interior is reminiscent of the Automat at Times Square. An establishment associated with vending machines and crowds is reduced to a sober scene without any others. Her self-conscious presence in an empty public space, puts the onlooker in the uncomfortable position of being an intruder.

Hopper’s painting communicates a narrative about modern life. Alienation (the state of being withdrawn from the urban world) was a theme that preoccupied sociologists of the 1920s and 30s.

Many Americans felt disconnected from traditional values and their sense of uncertainty is reflected in literature. F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and other novelists created disillusioned characters who felt lost in society. Hopper’s work linked with perceptions of alienation and disaffection. In “Automat” he captured the psychological make-up of the American social landscape of his age.

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: Edward Hopper’s “Automat,” 1927 (Des Moines Art Center, Iowa); Jacques de Vaucanson’s ‘Canard Digérateur’ (Digesting Duck), 1764; Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau in Paris, 1766; Horn & Hardart’s Automat on Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, 1904 postcard; Mark Twain dining at Delmonico’s, 1905 (Museum of the City of New York); and a typical Automat on 8th Avenue, 1937.

SALVAGED REMNANTS OF GOLDWATER LAMP PLACED IN RIOC STORAGE UNTIL PIECES CAN BE MADE INTO AN ARTWORK.

STAY TUNED……& SUGGESTIONS WELCOME.

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment