Friday, November 15, 2024 – THE BACK STORY OF THE STATUE OF LIBERTY

CHECK OUT OUR NEW INSTAGRAM POST”

https://www.instagram.com/roosevelt_island_history/?hl=en

THE STATUE OF LIBERTY:

CHEMISTRY, PSYCHOLOGY

&

DEMOCRACY

New York Almanack

Friday, Nov. 15, 2024

ISSUE #1344

The Statue of Liberty: Chemistry, Psychology & Democracy

November 12, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp

Although Thomas Coman (1836-1909) served as Acting Mayor of New York for several weeks at the end of 1868 and early 1869, Irish-born William Russell Grace (1832-1904) was New York City’s first elected Roman Catholic Mayor.

Elected in 1880 as the City’s 54th holder of the office, he had made a splendid career as an entrepreneur, but his candidacy was criticized in the editorials of the New York Times and lambasted by opponents who claimed that the new Mayor would hand the metropolis to the “Holy Father of Rome.” But attitudes towards “Popery” were changing as the number of Catholic Americans grew and their influence increased.

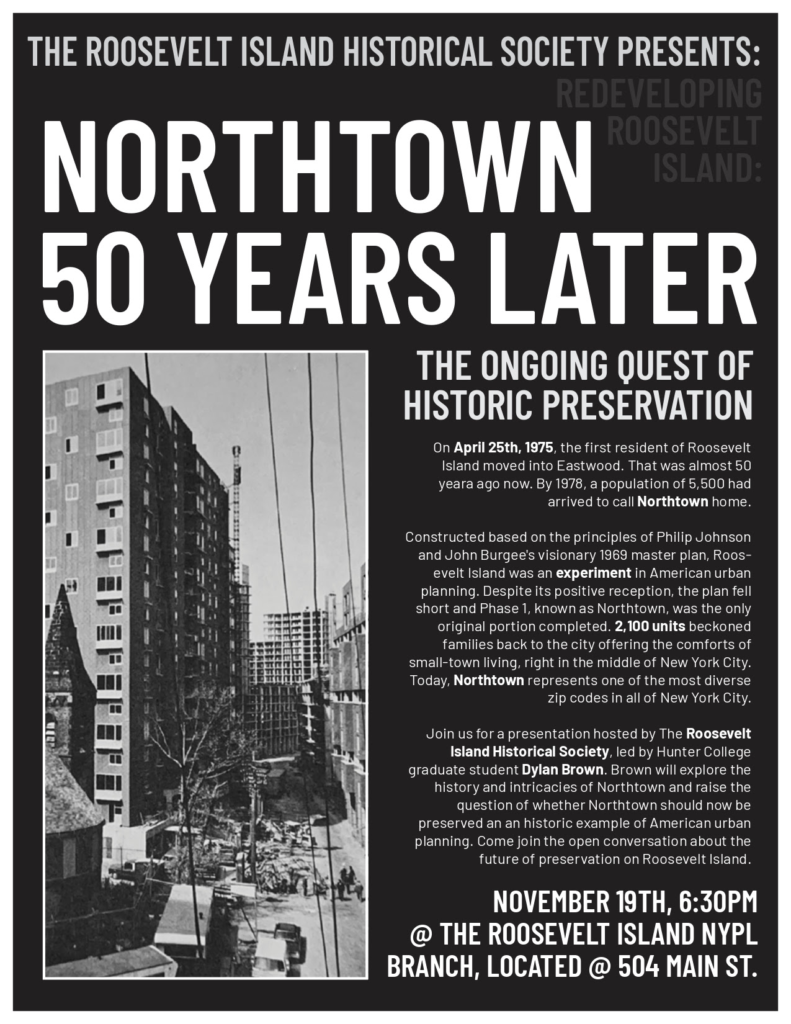

During his second term (as 56th Mayor), Grace gratefully accepted the Statue of Liberty as a gift from French citizens to the people of the United States. Towering over the entrance to New York Harbor, the monument would become the world’s iconic tribute to freedom and a beacon of hope for immigrants.

The history of its erection on Bedloe Island (renamed Liberty Island in 1956) highlights the diverse backgrounds and intentions of the project’s advocates.

Meeting of Minds

In June 1865 Édouard de Laboulaye invited a number of friends to dinner. A Professor of Comparative Law at the Collège de France in Paris, he was the author of a three-volume Histoire des États Unis (History of the United States) and translator of Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography. He supported the United States and acted as President of the French Association for the Abolition of Slavery during the American Civil War. He proved that Catholicism was not antithetical to liberal thinking.

The reason for this get together was to rejoice at the crushing of the rebellion against the United States. In his word of welcome, the host talked about an enduring friendship between the two nations and proposed that the French people should present the U.S. with a monument to celebrate its ideals of liberty and democracy.

Among the guests that evening was the sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi. Born in August 1834 at Colmar in the Alsace region, he was a former student of France’s most prominent architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc.

Having just returned from a trip to Egypt, he was fascinated by the monumental structures of Antiquity and had started designing a lighthouse named “Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia” to be located at the southern entrance to the Suez Canal, then under construction (it opened under French control in November 1869).

In the end, his grand statue of a woman holding a torch was rejected as too costly. Bartholdi embraced Laboulaye’s proposal instead. They called their projected statue “Liberty Enlightening the World.”

The 1870 Franco-Prussian War intervened. Serving as a squadron leader of the French National Guard, Bartholdi took part in the unsuccessful battle for control of Alsace. Outraged by the German takeover, he became an ardent advocate of political self-determination.

The deposition of Emperor Napoleon III was a positive outcome of the conflict. Elected to the National Assembly, Laboulaye participated in founding the Third Republic. The new political conditions were more conducive to generate support for his statue project.

Bartholdi envisaged creating a giant statue that would represent the democratic spirit of America. Armed with letters of introduction, he crossed the Atlantic in the summer of 1871 to gather support for the plan. During the journey he reworked his original Suez sketches and replaced the large figure of an Egyptian woman with “Libertas,” the Roman Goddess of Freedom.

As Bartholdi’s ship sailed into New York Harbor, he decided that Bedloe Island would be the perfect location for the monument. During that visit, President Ulysses S. Grant – the commanding General who had led the United States Army to victory against the Confederate States of America – promised him that using the site would be a possibility.

The Year 1876: Immigration Issues

In the decades following the Civil War, the United States emerged as an industrial giant with a railroad system that connected all parts of the country into a national market economy. Millions of people migrated from rural districts to cities that struggled to keep up with the pace of expansion.

Various crises in Europe saw the number of immigrants surge as America maintained open borders to settle its empty lands. By the mid-nineteenth century, streams of Chinese workers attracted by the California Gold Rush, entered the country. The influx of newcomers was seen as a necessity, but there were growing concerns about disunity and disharmony. Immigration became an issue.

Some states enacted statutes to limit the entrance of “unwanted” incomers, but these controls were challenged by stakeholders. The flow of destitute migrants from Europe and China to the United States offered lucrative opportunities for shipping lines. The interference of authorities impacted negatively on their economic prospects.

The case of Henderson v. Mayor of City of New York took place during the Supreme Court’s 1875/6 session. The Scottish Henderson brothers ran the Anchor Line, a merchant shipping company.

When SS Ethiopia arrived from Glasgow at New York Harbor, they challenged the statutes of New York and Louisiana that required ship owners to post a “bond” for landing immigrants that would cover indemnities in case any of them needed state support. The Court agreed with the plaintiffs, arguing that the responsibility for immigration policy rested exclusively with the federal government.

That same year, California’s Supreme Court came to a similar verdict in the case of twenty-two women (including a lady named Chy Lung) who had arrived from China in San Francisco on board SS Japan.

The immigration commissioner identified them as “lewd and debauched.” The ship’s captain refused to pay a (substantial) bond for their admittance, while Chy Lung resisted deportation. The Court decided in her favor, insisting that the federal government was in charge of immigration policy and diplomatic relations. It was not up to California to impose restrictions.

Having assumed command as a result of these verdicts, the federal government commissioned a study to determine the best place for a reception station in New York Harbor. By 1892, officers on Ellis Island began the inspection and processing of immigrants.

The Year 1876: Homage to Liberty

In the fourteenth century, Protestant Flemish weavers escaped Catholic persecution and settled in Lancashire where they established a textile “cottage industry.” The Industrial Revolution destroyed that economic pattern and unemployment rocketed.

There were few options. Workers could either work in the “satanic” cotton mills, join the army or emigrate. Considering their lineage, it is not surprising that the majority sailed towards New England.

Edward Moran was born in 1829 in Bolton-le-Moor, Lancashire, to a struggling family of handloom weavers. Set to work as a child, he found solace in sketching. In 1844, his parents moved the family to Maryland and settled in Philadelphia a year later. The youngster was employed in a textile factory. His supervisor recognized Edward’s artistic talent and encouraged him to pursue his interest.

Around 1845, Moran was apprenticed under Belfast-born James Hamilton who taught him the skills of marine painting. He was also instructed by Paul Weber, a German landscape artist – one of the “Forty-Eighters” – then living in Philadelphia.

In March 1871 Moran showed seventy-five paintings at James S. Earle & Sons gallery at Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, in an exhibition called “Land & Sea.” The show’s catalogue contained over seventy lithographs after the paintings. He donated proceeds from the exhibit to support the victims of the Franco-Prussian War.

The painter moved to Manhattan in 1872 where he lived until his death in 1901. An associate member of the National Academy of Design, he focused on New York Harbor scenes which were widely acclaimed.

Having met Bartholdi in 1876, he learned about the project. The idea inspired him. That same year he created an imagined spectacle of “The Commerce of Nations Paying Homage to Liberty,” which was then displayed at various fundraising events for the statue’s construction.

In the painting, “Lady Liberty” stands as a towering figure with a torch raised to the sky. In her other hand, she holds a tablet with the date of the Declaration of Independence. Surrounding her, a ceremonial scene shows a multitude of wooden boats with onlookers flying flags that represent different countries and communities. Moran’s image was a celebration of inclusiveness.

Franco-American Union

The response to Bartholdi’s first promotional trip to America had been disappointing. Undeterred, Laboulaye founded the Franco-American Union to raise funds. The statue would be constructed in Paris, whilst American participants were requested to finance the pedestal. The fact that French monarchists opposed the initiative was an additional motivation for him to press on with the plan.

Money was collected from all sections of society. A gathering at the Paris Opera on April 25, 1876, featured a newly composed cantata by Charles Gounod titled “La Liberté éclairant le monde.”

Industrialist Pierre-Eugène Secrétan donated 60,000 thousand kilos of copper to the project. The foundry of Gaget, Gauthier & Cie, located at Rue de Chazelles, was given the task of assembling the monument. Work started with the construction of head, arm and torch. Lady Liberty was born in bits.

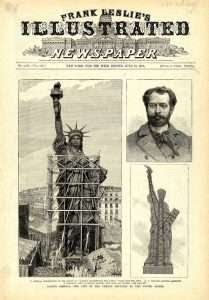

In May 1876, Bartholdi attended Philadelphia’s Centennial Exhibition. The completed arm and torch arrived too late for them to be recorded in the catalogue, but the exhibits became popular as the torch’s balcony offered a fine view of the fairgrounds.

These parts were then displayed at Manhattan’s Madison Square Park before being transported back to Paris. The head and shoulders were completed in 1878 and put on show at the Universal Exposition in Paris. The world started to take notice.

Viollet-le-Duc was invited to design the statue’s internal structure. The latter died suddenly in 1879 and Gustave Eiffel, then a promising engineer who specialized in metal construction, was employed to finish the job. The statue was assembled between 1881 and 1884. Parisians were astonished to see a colossal figure growing above the roof of buildings that surrounded the workshop.

Laboulaye encouraged his friends at the Union League Club to take responsibility for the pedestal. William Maxwell Evarts, President of the New York City Bar Association, took charge of the American Committee for the Statue (which included nineteen-year old Theodore Roosevelt).

Joseph Pulitzer, a Hungarian Jewish immigrant and publisher of the New York World, used his newspaper to promote the project. Richard Morris Hunt (architect of the Tribune Building at Printing House Square) was commissioned to design the pedestal. Construction started in 1884.

On July 4, 1884, the statue was formally handed over in Paris to Levi P. Morton, the American Minister to France (he was later U.S. Vice President and Governor of New York). Disassembled into 350 pieces, packed in 214 crates (thirty-six just for the rivets and bolts), it was transported by train to Rouen and shipped to New York aboard the Navy frigate Isère.

The French government borne the cost of the crossing, its only financial contribution to the scheme. Laboulaye would not see the final result of his determined efforts. He had died in May 1883.

On October 26, 1886, more than a million people attended the unveiling ceremony led by Grover Cleveland, former New York State Governor and the first Democrat President after the Civil War. In the presence of Edward Moran, Bartholdi revealed Lady Liberty’s face by removing the French flag that covered it.

The moment was greeted by cannon shots and ship sirens. Manhattan’s bells rang in the distance, while suffragists ridiculed the use of a female figure symbolizing freedom when women were denied the right to vote.

Chemistry & Psychology

The copper statue took four months to assemble and twenty years to transform from the original shiny reddish color into its iconic green through the natural chemical process of “patination” which prevented corrosion of the copper beneath.

Despite the statue’s age and exposure to the elements, the underlying structure remains unscathed. The change in color had a psychological effect too.

Laboulaye was a figure with lofty liberal ideals. His concept of a Statue of Liberty was intended as a tribute to freedom and equality (and the abolishment of slavery). From the outset he had his own agenda.

As Napoleon III’s Second Empire was a repressive regime, the proposed gift to the American people was an attempt to infuse the ideals of Republican democracy into the consciousness of fellow French citizens. At the early stage of instigation, the plan was an act of political rebellion.

The son of a Protestant counselor to the prefecture, Bartholdi received a liberal education. Having experienced the loss of Alsace to German troops, his stance took a sharper political edge. Witnessing deep divisions within Europe, his interpretation of the project was as much an alarm call as it was a salute. His message had an undertone of gloom.

Edward Moran on the other hand was an immigrant whose family members had escaped grinding poverty in Lancashire. He proceeded to become a celebrated artist. He joined the Liberty project to honor the country that had freed him from the shackles of deprivation.

To all these participants, the copper color of Lady Liberty was a metaphorical red warning light: if democracy and peaceful co-existence were not established in the “Old Continent,” then America would become an alternative to disillusioned Europeans.

That perception modified over time. As the Statue of Liberty was visible from every ship approaching New York Harbor, it provided a first glimpse of the new “promised” land to countless immigrants. She emerged as the “Mother of Exiles,” giving a green light of hope and expectancy to millions of newcomers.

THE SLEIGH IS BACK ON THE CHAPEL PLAZA!!

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARSKAMP

JUDITH BERDY

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment