Weekend, December 27-29, 2024 – A PERFECT NEW YEAR’S DAY***BAGELS & LOX

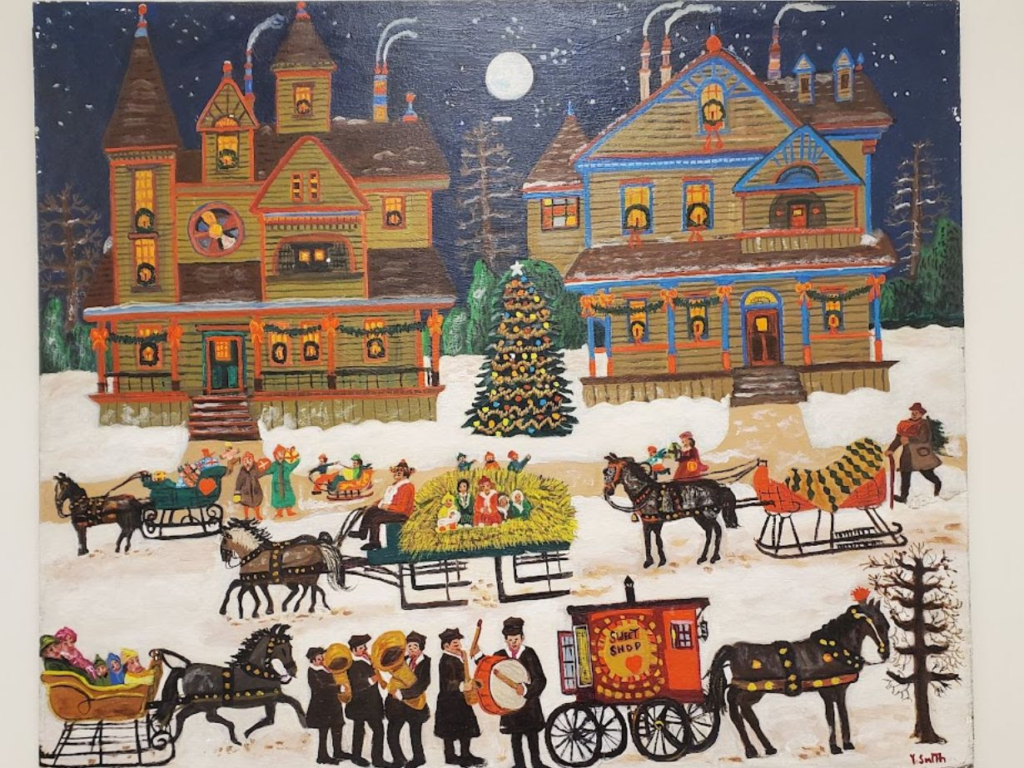

HOLIDAY SCENE

BY YVONNE SMITH

RESIDENT GOLDWATER HOSPITAL

COLLECTION OF NYC H+H COLER

NEW YORK CITY

BREAKFAST:

CREAM CHEESE, BAGELS & LOX

DECEMBER 27-29, 2024

ISSUE #1365

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARSKAMP

JUDITH BERDY

HAPPY CHANUKAH AS WE CELEBRATE THE

FESTIVAL OF LIGHTS

Manhattan Breakfast: Cream Cheese, Bagels & Lox

December 24, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp

Friends and strangers eating together offers an appealing image of togetherness. “Let us build a table where everyone is invited,” is an inspiring mantra. At the same time, food is a religious symbol that creates exclusion.

Food taboos appear in almost all societies, either self-imposed or enforced by authorities on minority groups. In medieval Europe, Christian authorities forbade Jews from baking “sacred” bread.

Different ethnic and religious groups identify themselves by the foods they consume or refuse to eat. A food taboo maintains a group’s identity in the face of others, creating a sense of belonging.

If such a ban limits the diet, it also encourages the consumption of symbolic foods particular to that group. Jewish tradition marks every calendar event (birth or death) with a special meal. Circular shaped bagels symbolize the lifecycle.

Bagels once were a Jewish specialty. First boiled and then baked, its preparation method gave the bread a chewy outer texture and soft dough within. The bagel was brought to Manhattan in the 1890s by Polish immigrants of the Lower East Side.

Longing for the breads of their homeland, they recreated rye, challah and above all: bagels. For decades bagels remained an exclusive ethnic delicacy. Taste and nostalgia are inseparable.

A multi-cultural metropolis demands coexistence and does not function properly in an environment of selective restrictions. At New York City’s collective dining table many traditional food taboos – either voluntarily or by necessity (hunger or scarcity of ingredients) – were overcome.

Since the 1950s, bagels have conquered Manhattan’s foodscape and permeated American culture.

Cream Cheese & Cheesecake

Jewish immigrants Isaac and Joseph Bregschtein from Panemune on the banks of the Nemunas River, Lithuania, settled in the United States in 1882, initially working as peddlers and (possibly) living in Pennsylvania.

By 1885, they had arrived in Manhattan where Joseph opened a grocery store at 27 Orchard Street. Isaac continued to deal in dry goods until 1888, when he entered the dairy market, selling milk and other products. At some time, they anglicized their name to Breakstone.

They quickly built a reputation in the world of dairy. Their cousins Morris and Hyman – a typical case of chain migration – owned stores of their own. In 1897, the family members joined together as the “Breakstone Brothers” and opened a grocery.

The name was copyrighted in 1906 and a year later the group began manufacturing dairy products at a small plant in Brooklyn.

At a time that many American households made their own butter and soft cheeses, the Brothers brought convenience by selling the products from big wooden tubs.

The company was among the first to use trucks to deliver their products. During the First World War, Breakstone’s was the largest producer of condensed milk for the Armed Forces.

After the war, the firm started to mass market their products to consumers, making soft cheeses and other products affordable to many poorer Jewish consumers. In 1925, Breakstone’s began designating their products as “kosher.” The brand played its role in the identification of New York City’s passion for cream cheese with the story of Jewish immigration.

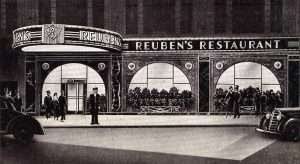

New York style cheesecake, which used cream cheese instead of drier ricotta or cottage cheese, was introduced in 1929 by German-born Jewish restaurateur Arthur Reuben in his legendary outlets Reuben’s Restaurant at 58th Street and the Turf Restaurant at 49th and Broadway.

Also known as “Jewish cheesecake” for the recipe’s kosher ingredients, it was a favorite of actors and actresses seeking late night relaxation after stage appearances.

The taste of cheesecake quickly became the rage of the city, but the story of its origin was in dispute. Reuben accused Leo Linderman, another German-born Jewish restaurateur, of copying his recipe and making it his own.

Lindeman owned Lindy’s, a Jewish delicatessen on Broadway which marketed its cheesecake (produced with Philadelphia cream cheese) as its iconic dish. Considered a masterpiece of Jewish culinary skills, it became the gold-standard in cheesecake baking. And yet …

No Success Like Failure

The history of cream cheese is an essential American tale. Early English and Dutch settlers had brought recipes for something tasting similar. At the turn of the nineteenth century, small producers of cream cheese could be found in the Philadelphia area, but it was in Upstate New York that the first large-scale manufacture of the product began.

Orange County was officially established on November 1, 1683, when after nearly two decades of English rule the Province of New York was divided into twelve counties. Each of these was named in honor of Charles II, his brother James, Duke of York, and other members of the Royal family.

Orange County referred to Dutch-born William of Orange, James’s son-in-law and subsequently King William III of England. Within the next few decades Dutch, English and German Palatine migrants began populating an area that consisted of fertile farming land.

The town of Chester’s economy in Orange County was based on dairy products, particularly milk. This industry flourished after completion of the Erie Railroad in 1841. The line ran through the town which enabled local farmers to ship their products directly to New York City, where demand was high. Chester became the original home of American cream cheese.

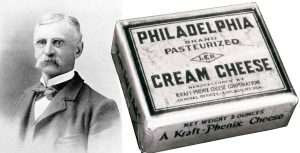

In 1872, dairyman William Lawrence was challenged by a Manhattan deli owner to produce a new fresh cheese that would please the taste of affluent customers. William tried to duplicate the popular French soft cheese brand of Neufchâtel, but did not succeed.

His failure became a massive success. He discovered and developed the formula for Philadelphia Cream Cheese. Although not created in that city, Lawrence adopted the name because of Philadelphia’s reputation for producing high-quality cheeses at the time.

Lawrence was the first to sell soft cheese in foil-wrapped rectangular packages and ship them to markets in New York City. At the outset, his creamery delivered about two boxes daily. By the time of his death in 1911, the factory was producing over two thousand boxes each day.

Lawrence’s cheese making operation had a major impact on the local economy. He employed rural residents and used regionally sourced milk in his cheese production. Although not an aspiring politician, he was elected Mayor of Chester in 1893.

James Lewis Kraft, a Canadian businessman of German descent living in Buffalo, NY, purchased the business in 1928. The company continues making Philadelphia Brand Cheese to this day. By the 1950s cream cheese had become an all-American staple without any particular ethnic or migrant ties.

A quintessentially New York creation, cream cheese has since proliferated throughout nation, touching disparate cuisines and inspiring multiple recipes.

Bagel Mania

In the early medieval period, a form of round bread similar to the “pretzel” became popular among German-speaking migrants to an area of Eastern Europe which (roughly) now constitutes Poland. In the region, bakers suffered less intervention in their profession than other Jews whose activities were severely restricted by segregation laws.

They were permitted to sell products to Christian residents who, when abstaining from rich foods during Lent, consumed a boiled and ring-shaped bread known as “obwarzanek.” They also enjoyed a smaller version for everyday consumption which was known as “bajgiel” in Polish and “beygal” in Yiddish.

The delicacy soon spread throughout the region and was sold by licensed street hawkers from a basket or hanging on from a stick.

The bagel became a Jewish staple in Poland. When in 1908 Isaac Bashevis Singer described a childhood trip to Radzymin (a suburb of the city of Warsaw) in “A Day of Pleasure,” he recorded the sight of sidewalk peddlers who were selling “loaves of bread, baskets of bagels and rolls, smoked herring, hot peas, brown beans, apples, pears and plums.”

Polish Jews brought the bagel to Manhattan. Their first known bakery was established on the Lower East Side in 1895. Twelve years later, the powerful International Beigel Bakers’ Union was created which monopolized New York’s bagel production.

The all-Jewish union carefully guarded knowledge of how to bake the bread and urged Jewish customers to buy from associated shops instead of giving their business to owners who were likely to exploit newly arrived immigrants. For decades, bagels remained an ethnic delicacy, virtually unknown to society at large.

The invention and adoption of a bagel-making machine spelled both the downfall of the Union and a widening interest in the product. The post-war years were a turning point. Food writers such as Fannie Engle, author of The Jewish Festival Cookbook (1954), popularized the bread at a time that Jews were assimilating and sharing their culinary traditions with others.

The bagel made an eye-catching appearance in the Yiddish-English revue Bagel and Yox (the word means “belly laugh”) that ran at the Holiday Theatre, Broadway, from September 1951 to February 1952. It included the song “Bagel & Lox” (written by Sid Pepper and Roy C. Bennett):

Bagel and lox with the cheese in the middle,

Bagel and lox let it toast on the griddle,

Bagel and lox with the cheese in the middle,

And a slice of onion on the side.

During the show’s intermission, freshly baked bagels were handed out to members of the audience. A 1951 review of the show published in Time magazine helped to hype them amongst American consumers. A passion for bagel and cream cheese erupted. It would take some more time before the addition of lox completed the “holy trinity.”

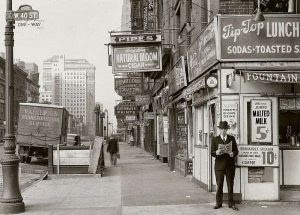

Iconic Breakfast

According to food historians, Jewish shopkeepers were selling preserved salmon by the early twentieth century, using recipes introduced by Scandinavian immigrants. Soon, lox and cream cheese were prized breakfast accompaniments. Newspapers in the early 1940s reported that bagels and lox were sold in Manhattan delis as a “Sunday morning treat.”

Lox is a fillet of salmon cured in salty brine, but not cooked or smoked. Known as “gravlax,” it was a Nordic method of preserving fish long before refrigeration was made available. The salmon was coated with a spice blend of dill, capers, juniper berry, salts, sugars and liquors, before being brined. Lox was also popular among Eastern European Jews (the word lox comes from the Yiddish “laks,” meaning salmon).

The Transcontinental Railroad helped to popularize lox as trains transported salted salmon from the Pacific coast to New York City. Bagel and lox became a Manhattan sensation. Spurred on by Kraft’s advertizing blitz for Philadelphia Cream Cheese, the Sunday morning ritual of lox, bagel and cream cheese took off.

This was as an American food concoction, a collage consisting of Polish Jewish bread, Scandinavian cured salmon, Mediterranean capers heaped over Anglo-French styled cream cheese. At some point by the middle of the twentieth century, Lox Bagel had replaced the English trilogy of bacon, eggs and toast as Manhattan’s breakfast of choice.

Read more about New York State’s culinary history.

CREDITS

JUDITH BERDY

NEW YORK ALMANACK

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment