Monday, February 10, 2025 – THE MANY HOMES AND COMPLICATIONS OF THE N-Y HISTORICAL SOCIETY

History on Central Park West:

Building a Home for Art and Culture

Monday, February 10, 2025

ISSUE #1392

by Sara Cedar Miller

in From the Stacks

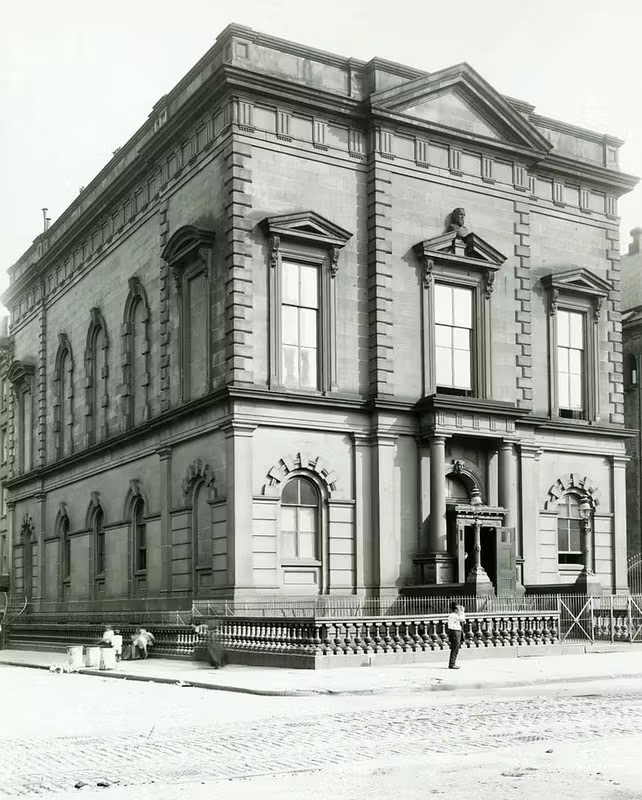

The New-York Historical Society was founded in 1804 and operated out of rented or donated spaces for about half a century before it settled into its first permanent home in 1857 in the fashionable neighborhood located around Second Avenue and 11th Street. However, the Society’s ever-expanding collections almost immediately demanded more space.

Box 1, Folder 2, New-York Historical Pictorial Archive.

New-York Historical’s leaders considered the new Arsenal building uptown at 64th Street and Fifth Avenue, admired for its green surroundings in the city’s most exciting new attraction—Central Park. The Society sought approval for their move from the New York State legislature and the Central Park Board of Commissioners and put plans in action to renovate the fortress-like building, which was designed in the 1850s as a storage repository for munitions.

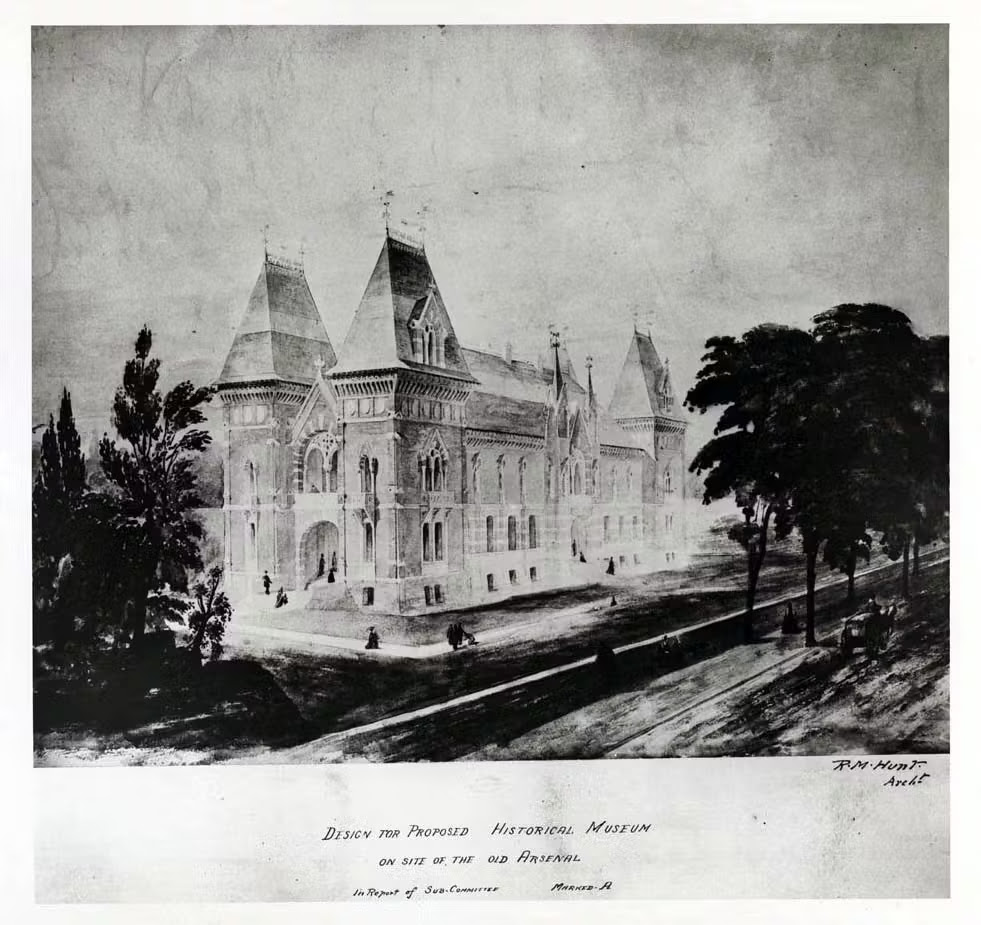

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

In 1862, New-York Historical enlisted the talents of the young, Paris-trained architect Richard Morris Hunt who proposed to transform the mundane military Arsenal into a whimsical neo-Gothic French chateau. Discord brewed between the Society and the commissioners of Central Park over Hunt’s plans. Their disputes centered over the proposed size and managerial control of the property and a strict completion date for the new construction.

By 1866, negotiations about the Arsenal building came to a head and the leaders of New-York Historical settled on an entirely new site, stretching from 79th to 84th Street along Fifth Avenue—the grounds that now house the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They again enlisted the talents of Richard Morris Hunt to design a building on this site on the Upper East Side.

Once again, New-York Historical encountered numerous hurdles and objections from the Central Park board of commissioners. They found their plans stymied by spatial constraints and were unable to raise the necessary funds within the city’s required three-year window. Moreover, the Society flatly refused one of the demands made by Central Park leaders: to set aside office space in their building for the park commissioners. In the meantime, the New-York Historical Society remained in the Lower East Side until the 1880s, when they once again prioritized relocation. This time, the Society initiated a concerted fundraising campaign to purchase property and construct a new building.

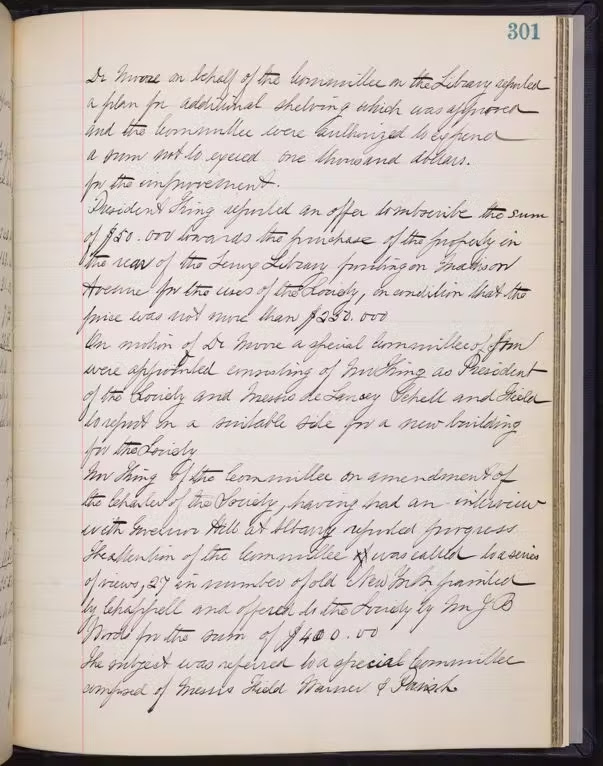

Various Manhattan real estate agents offered a trove of tantalizing properties to the building committee. Many of these prospects hovered close to Central Park. Remarkably, several of the properties rejected by the committee have since become some of New York’s most iconic landmarks: the Juilliard School at Lincoln Center, the Hearst Building, Carnegie Hall, and the General Motors Building at the southeast foot of Central Park (now home to an Apple Store). The committee even sent out an inquiry in May 1889 (recorded in the meeting minutes below) to the Lenox Library, located at Fifth Avenue and 70th to 71st Streets—the site of today’s Frick Museum—to inquire about the availability of the eight lots located behind the library on Madison Avenue.

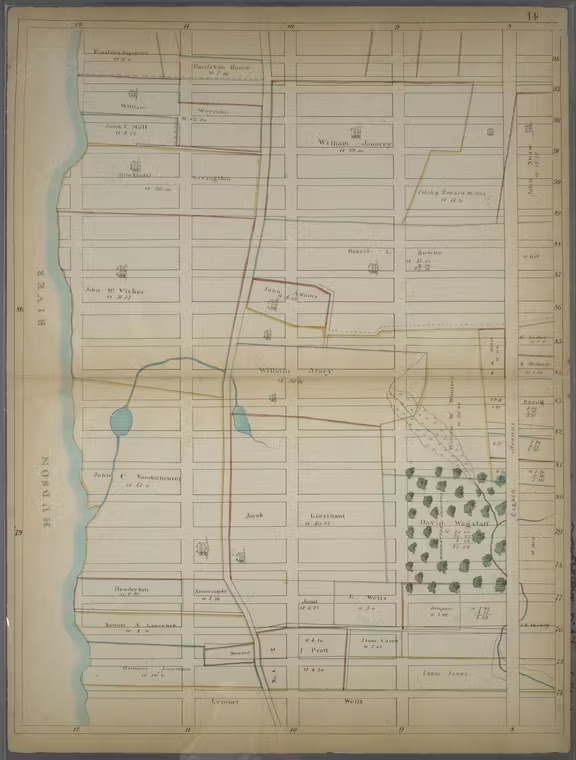

Finally in February 1891, the building committee purchased 10 lots of land on Central Park West between 76th and 77th Streets, New-York Historical’s current location. Curiously, the Society’s records do not contain any evidence of an agent’s proposal for these lots of land. It seems highly probable that the lots were not on the open market, but that Robert Schell, the treasurer of the Society and a member of the selection committee, made the deal possible. In 1890, Schell himself acquired a lot on Central Park West for $38,000 from landowner Harriet Fearing and then sold it to the Society the following year for the exact same amount. The total purchase price for the ten lots was $286,500.

Before it became home to the New-York Historical Society, the lots on Central Park West changed ownership several times during the 19th century. David Wagstaff, a wealthy merchant, farmer, and civic leader, acquired the land between 76th and 77th Streets as part of his estate in 1811. Among his assorted holdings, he loved his country home at the crossroads of Fifth Avenue and the 79th Street Transverse Road. In the 1820s, Cedar Hill (now Central Park’s beloved winter sledding hill) was part of Wagstaff’s estate where he cultivated asparagus, which he considered “among the finest brought to market.” It was on his Cedar Hill estate, complete with an icehouse and greenhouse, that Wagstaff and his wife Sarah raised their five children.

When David died in 1824, he bequeathed the lots on his half block between 76th Street and 77th Street to his three daughters and his son, who also served as the executor. Like their father, the four Wagstaff children held on to their property, recognizing its worth as a valuable investment. However, the next generation (David Wagstaff’s grandchildren) cashed in on their inheritance. In 1887, developers had begun constructing an unbroken string of residential rowhouses on West 76th Street and in 1890, Charles, William, and Caroline Lowerre sold three of the lots (1, 3, and 5 West 76th Street) to real estate speculator William B. Baldwin. Baldwin announced plans to erect carriage houses on a wide plot stretching along the north side of 76th Street, a prospect that ignited vehement opposition from the block’s wealthy landowners. They argued that having carriage houses in their midst would surely ruin their property values. Within months, the neighboring landowners collectively bought back the large plot from Baldwin at a higher price and created a legal agreement that only allowed the construction of private dwellings, the largest houses going up closer to Central Park. The Real Estate Record and Builder’s Guide applauded the result of such actions on West 76th Street to “raise the standard of buildings… against nuisances and cheap structures… [and admit only] a desirable class of residents” (May, 30, 1891).

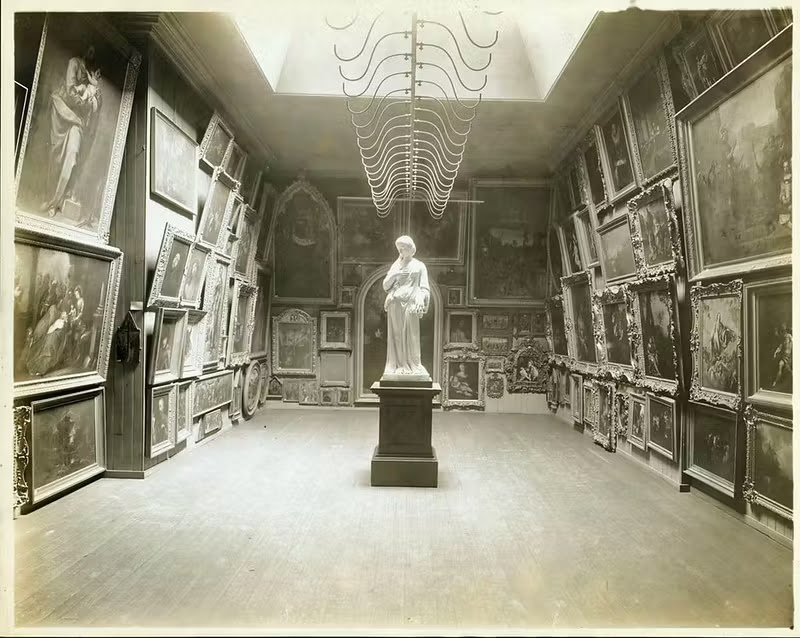

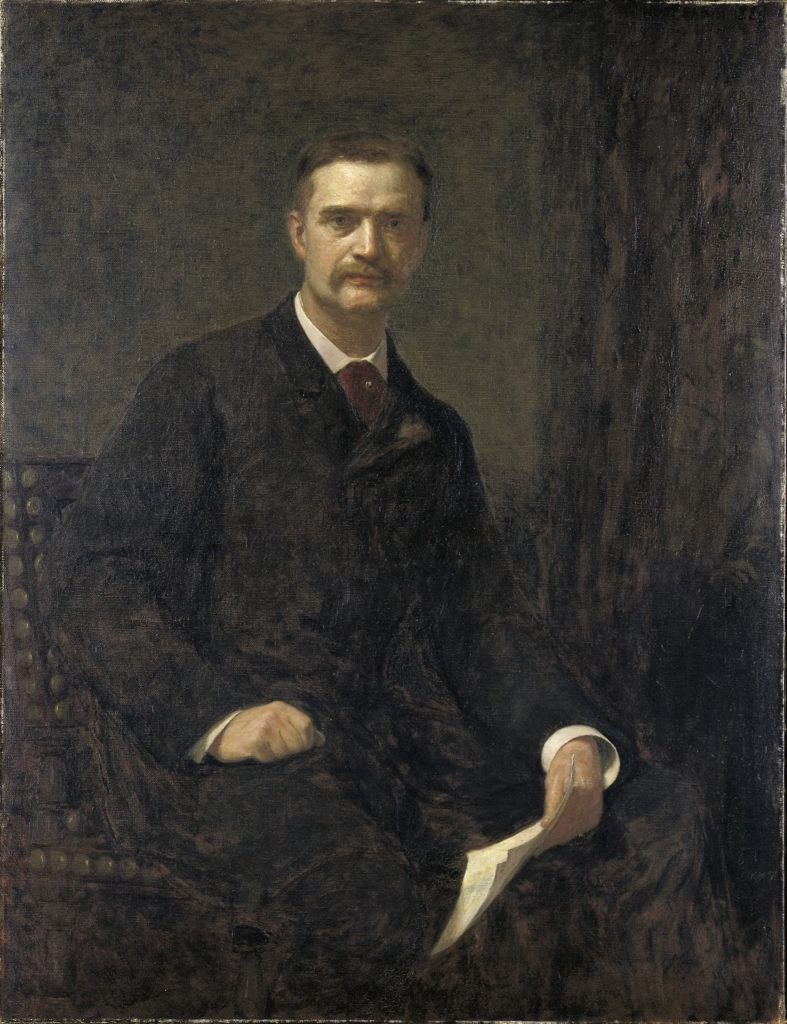

In 1890, Irish immigrant William T. Evans and his wife Mary purchased three lots formerly owned by Baldwin. Evans had amassed his fortune by investing in real estate and moving up the ladder to become president of Mills & Gibb, a New York firm that imported silk, linen, and dry goods. Though Evans had initially studied architecture, his passion for art had made him a major collector of masterpieces by the early 1880s. The same year he acquired his 76th Street lots, he surprisingly sold off his entire European art collection, largely consisting of French oils. In their place, he became a champion of American artists, whose works at the time were deemed inferior and financially risky by the art world’s cognoscenti. Evans befriended, corresponded with, and collected the works of such American artists as George Inness, Winslow Homer, Albert Pinkham Ryder, Childe Hassam, John Twachtman, Mary Cassatt, Ralph Blakelock, Worthington Whittredge, Frederick Remington, Albert Bierstadt, Winslow Homer, Rembrandt Peale, and Eastman Johnson.

Evans set out to design a sumptuous brownstone on the widest of his three lots (no. 5) where he could exhibit his new acquisitions. The four-story residence on 76th Street boasted a spacious gallery at the rear of the house which he quickly filled with American works. But his passion for art knew no bounds, spilling into every nook and cranny of the home. Art critic Charles De Kay marveled at how the collection “lights up the walls of drawing, dining room and vestibule, [and] overflows into the corridors, mounts the staircase, and invades the billiard room and sky parlor.” The Evanses opened their doors to visitors on Sunday afternoons from November to May, allowing people to enjoy their collection. In 1892, the Evanses sold their two other plots on 76th Street (lots 1 and 3) which buttressed their home to the New-York Historical Society. In March 1901, the family sold their brownstone in New York and moved to an even larger mansion in Montclair, New Jersey, likely to accommodate their growing art collection and their seven children.

During the first decade of the 20th century, Evans continued his relentless pursuit of American art, buying it at an even more feverish pace than before. In eight years, he purchased more than 200 artworks. His buying spree carried on until 1913, when Evans’s shocking secret was revealed. Unbeknownst to his friends and family, and shrewdly concealed from his colleagues at Mills & Gibb, Evans had illegally withdrawn more than $700,000 from the company’s accounts to fuel his insatiable passion. Evans sold much of his cherished collection in 1913 as well as his opulent Montclair mansion and other valuable properties in 1915. To make amends perhaps, Evans donated 160 paintings to the National Gallery in Washington (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum) as well as 60 other artworks to smaller museums in New Jersey. The firm of Mills & Gibb went into receivership in 1916 and he died two years later of, according to his obituary, a “general breakdown caused by illness and overwork.” It was a tragic conclusion to the illustrious career of one of the earliest and most fervent patrons of American art.

The next and last installment of this series will chronicle the story of Oscar and Sarah Straus, who bought the Evans’ home on 76th Street as well as several other fascinating landowners, who sold their lots to the New-York Historical Society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

COMING TO THE NYPL BRANCH ON

FEBRUARY 18TH

SAY NO TO THE LOO

At this weeks RIOC Real Estate meeting, they introduced the idea of placing “Portland Loo” public bathrooms near the Firefighter’s Field/Tram area to serve the public.

RIOC staff did not provide and image. I pulled one up on my phone and the reaction was very negative to this metal structure.

Imagine this in the heat of summer or the cold of winter!

(reminds me of Paris Pissoirs of days past).

It is ugly and completely inappropriate to our island.

CREDITS

NEW -YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Sara Cedar Miller is the historian emerita of the Central Park Conservancy, which she first joined as a photographer in 1984. Her most recent book is Before Central Park (2022).

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment