Wednesday, February 19, 2025 – HOW THE FOUNTAIN ARRIVED IN CENTRAL PARK

Emma and the Angel of Central Park:

A Talk with Maria Teresa Cometto

Wednesday, February 19, 2025

ISSUE #1399

FROM THE STACKS

NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

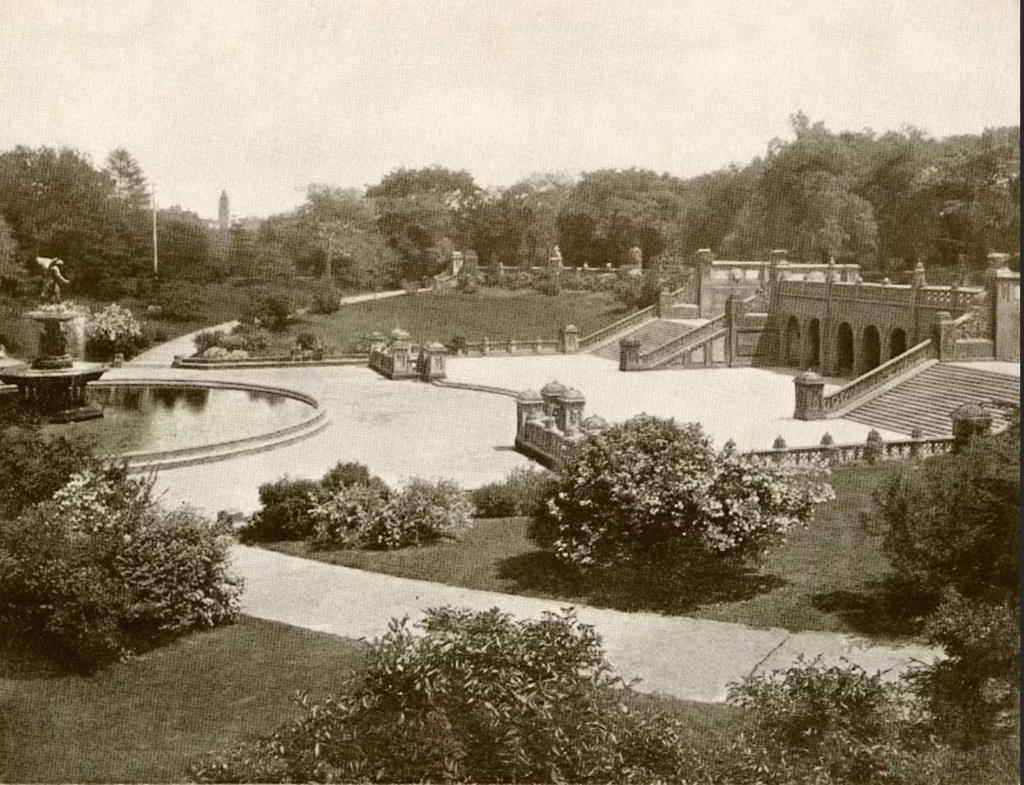

As our 2023–24 exhibition Women’s Work enters its final weeks, we at the Center for Women’s History are in a reflective mood. New York City doesn’t always lend itself to quiet introspection, but it’s worth remembering that, even among the hustling pedicabs and bustling bridal parties, Central Park was created expressly for this purpose. Park architects Frederick Law Olmstead (1822–1903) and Calvert Vaux (1824–1895) sought to provide weary urbanites with a peaceful oasis—a beautiful, pastoral setting in which they could refresh their bodies and minds.

And at the center of the Park lies the Bethesda Terrace with its iconic fountain, topped by the Angel of the Waters. “This is my favorite place in New York City,” reflects Prior Walter in the Epilogue of Tony Kushner’s award-winning Angels in America. “No, in the whole universe, the parts of it I have seen…This angel. She’s my favorite angel. I like them best when they’re statuary…They are made of the heaviest things on earth, stone and iron, they weigh tons but they’re winged, they are engines and instruments of flight.”

The Angel of the Waters in Bethesda Terrace is all of those things and more. Based upon a passage from the Biblical Book of John, the fountain was commissioned in 1863 to commemorate the completion of the Croton Aqueduct and the incalculable benefit it brought to New York in the form of clean drinking water. As such, it symbolized a major victory in the fight against cholera and the other deadly diseases that plagued the 19th-century city.

The Angel of the Waters also represents a landmark in women’s history. As journalist and author Maria Teresa Cometto writes, it is “the first and only sculpture commissioned as part of the Central Park plan and funded with taxpayer money,” and the artist, Emma Stebbins, was “the first woman in New York City to be commissioned to create a large work of public art.” Stebbins, though born into a wealthy and well-connected New York family, created the Angel in her studio in Rome. She had gone to Italy in 1857 to study sculpture and live in a community of like-minded, independent women artists. Among them was the famous 19th-century actor Charlotte Cushman, acclaimed for her facility in playing male roles, including Romeo and Hamlet. Stebbins and Cushman maintained a romantic relationship for many years, and it is thought that Stebbins may have modeled the figure of the Angel after her gender-bending partner. In addition to acting, Cushman worked as a model; a bust representing her form is currently featured in our special exhibition, Women’s Work, alongside a discussion of her relationship with Stebbins.

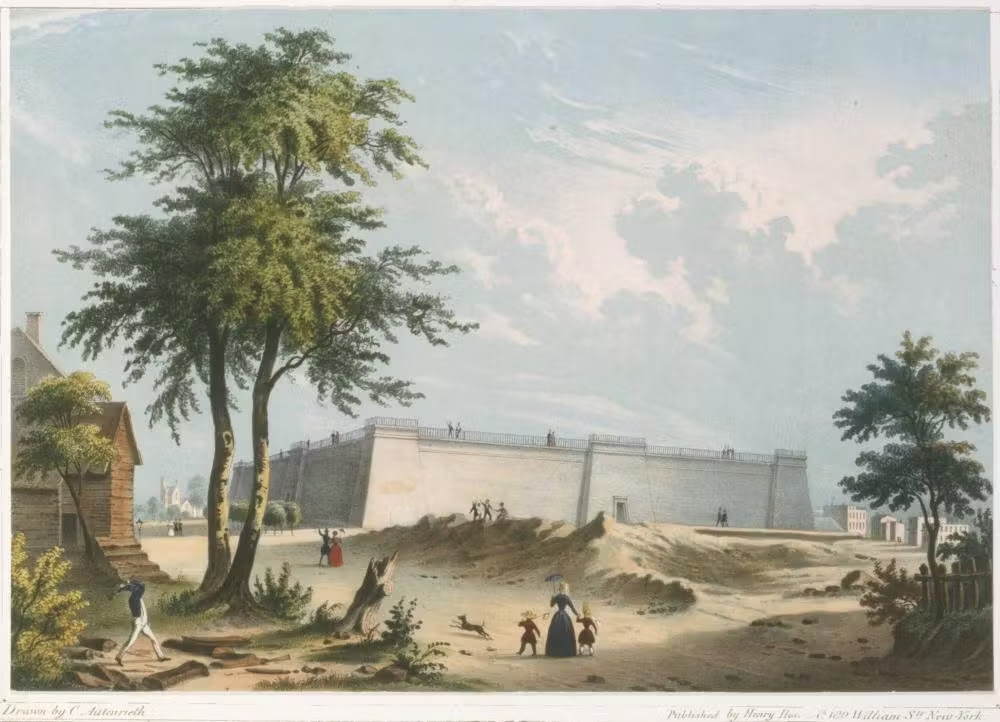

Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept New York, the city celebrated the opening of the Croton Aqueduct, which brought fresh water from what is now Westchester County to this reservoir, which occupied the site where Bryant Park and the New York Public Library’s Schwartzman Building now stand. You can learn more about the Croton Aqueduct at our exhibition Lost New York, on view until September 29, 2024.

To learn more about Stebbins, we spoke with Cometto about her recent biography of the artist, entitled Emma and the Angel of Central Park. Our conversation appears below, lightly edited for length and clarity:

Ten years after a cholera epidemic swept New York, the city celebrated the opening of the Croton Aqueduct, which brought fresh water from what is now Westchester County to this reservoir, which occupied the site where Bryant Park and the New York Public Library’s Schwartzman Building now stand. You can learn more about the Croton Aqueduct at our exhibition Lost New York, on view until September 29, 2024.

To learn more about Stebbins, we spoke with Cometto about her recent biography of the artist, entitled Emma and the Angel of Central Park. Our conversation appears below, lightly edited for length and clarity:

Miss E. Stebbins (Emma Stebbins, 1815-1882), Cartes de visite portraits of nineteenth century artists, 1856. American Art and Portrait Gallery Collection, Smithsonian Institution.

Emma Stebbins is a rather opaque figure. As you write in your Introduction, she was “very shy, reserved… she left no diary, she destroyed her private correspondence with Charlotte [Cushman]…here are few traces of her in the archives of universities, museums, and research centers, from New York to Rome.” Why do you think this might be the case? And given her enigmatic nature, what prompted you to take on Emma Stebbins as a subject?

“(I am) a soft-shelled crab, forced by circumstances into hard-shelled positions.” This is how Emma Stebbins described herself. So yes, Emma was very shy and reserved. She destroyed the letters she exchanged with Charlotte [Cushman] because Charlotte had asked her to: they were too scandalous and would have compromised the image of Charlotte herself, the very famous actress happy to be remembered as a “virgin queen of the dramatic stage,” as the New York Times wrote in her obituary.

As for me, I am a journalist, curious by nature. I was struck by the gap between the popularity of the Angel of the Waters versus the silence about the artist who created it. Even today, very few know the story of this iconic New York monument and the woman behind it. My book is the first and only biography of Emma Stebbins. I decided to write it when I started looking for news on the Angel of the Waters—which I love very much—and I realized that its creator, Emma Stebbins, was a true pioneer as an artist and as a woman who, together with her companion Charlotte Cushman, defied prejudice and social conventions, living openly as a married couple 150 years before marriage equality in the United States.

Although we often think of artists as solitary geniuses toiling alone in their studios, you’ve demonstrated that Emma Stebbins was part of several very distinguished social and artistic circles, through both her family of birth in New York and later, her chosen family in Rome. Can you describe some of the key players in Stebbins’s life, and how they impacted her and her career?

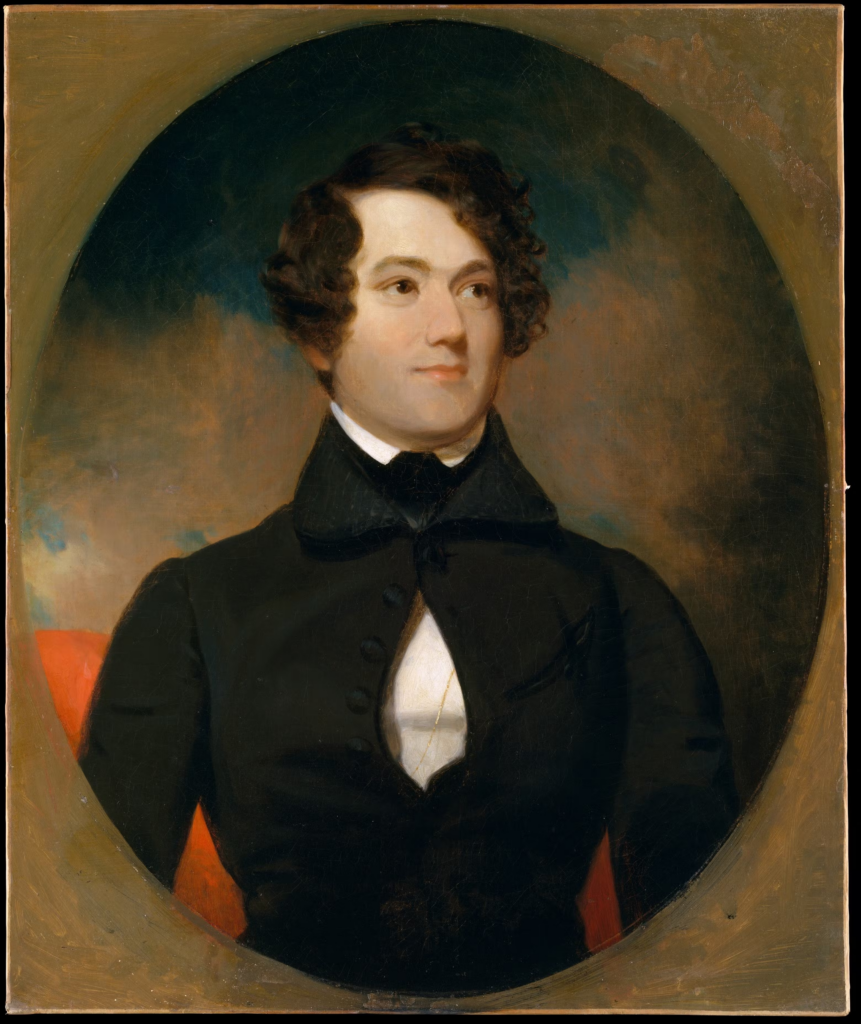

The first key player in Stebbins’s life was her brother Henry, an early supporter of her artistic career. He was president of the New York Stock Exchange and a patron of the arts— one of the founders of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in fact. He was also a commissioner of Central Park, which led some critics to say Emma got the commission for the Bethesda Fountain because of nepotism. But she was already pretty famous when she got the commission, and Henry Stebbins was always praised as an upstanding citizen, devoted to improving life in New York and fighting corruption.

The other key player was Charlotte Cushman. As I wrote in my book: “Strong, decisive, passionate, a shrewd steward of her own image and financial fortune, Charlotte was also generous to her expatriate artist women friends in Rome. She hosted them, helped them, promoted them within the art world, and defended them from the envy and attacks of male competitors.” Emma became part of Charlotte’s “family” when she moved to Rome in 1856. And Charlotte became not only her partner but also took on a managerial role, helping her solve all the practical problems of artistic activity, from getting commissions to getting paid.

Henry Inman (1801-1846), artist. Henry G. Stebbins (1811-1881), 1838. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Josephine S. Stebbins, 2001.269

Emma Stebbins’s process was different from other sculptors of her time; you mention that Stebbins insisted on “being 100 percent the author of her sculptures,” which was not the way that her contemporaries and friends (such as Harriet Hosmer or Edmonia Lewis) worked. How would you characterize the differences between these artists, and how did Stebbins’s creative process affect her career?

Harriet Hosmer and Edmonia Lewis worked as all neoclassical sculptors did, starting with the master of neoclassicism Antonio Canova. They employed Italian craftsmen to rough out marble blocks based on their models and then engaged with the chisel only in the final stage of statue creation. (Indeed, access to high-quality Carrara marble, skilled yet affordable assistants, and nude models—none of which were readily available in the United States—was the reason why so many women artists made their way to Rome.) This process allowed Hosmer and her colleagues to make several copies of their more popular and successful statues.

In contrast, Emma did everything herself, with maniacal perfectionism. It was a matter of professional pride and a desire to be independent, to maintain control of her work, without interference. So Emma limited much of her production to small statues and didn’t make many copies of her statues. But the hours and hours spent using hammer and chisel on marble, breathing in the dust, were harmful to the lungs and eventually proved fatal to Emma.

You’ve gathered so many interesting stories about the creation of the Angel of the Waters, it’s difficult to focus on just one—but if there was one thing that you wanted everyone who saw this statue to know, what would it be?

I would like to draw attention to the fact that for Emma, the Angel is a woman. When she explains the significance of the Angel of the Waters in the program printed for its inauguration, she speaks of her angel as a woman: “She bears in her left hand a bunch of lilies, emblems of purity, and wears across her breast the crossed bands of the messenger-angel. She seems to hover, as if just alighting on a mass of rock…”

It struck me, because it is not a customary way of depicting angels. In the collective imagination the association of angels with the male gender prevails. The cherubic angels are definitely male, and the Archangel Michael is a warrior, wielding a sword to defeat the dragon, that is, evil.

In fact, the Angel of the Waters has a woman’s breasts, although overall the body is as powerful as a man’s. The face, on the other hand, is androgynously beautiful. So Emma’s statue anticipates by a century and a half the concept of gender fluidity. Its beauty also lies in being open to ever new interpretations, which is the essence of true art.

The Angel of the Waters took a long time to plan and execute, and it had a very fraught journey from Emma Stebbins’s studio in Rome, to the foundry in Germany, to its final placement in New York. Can you describe the statue’s journey, and some of the problems that stood in its way? And, in the end, when it was finally installed, how was the statue received?

It took 10 years for the Angel of the Waters to appear in Central Park. It was 1863 when Emma got the commission, and 1873 when the fountain was finally inaugurated. One reason is that Emma was a perfectionist: it took her four winters, between 1864 and 1867, to create the clay and plaster models of the Angel and the fountain. But Emma was also unlucky. In 1869 the statue arrived in Munich to be cast at the Royal Foundry, the best in the world for artistic works. But because of the Franco-Prussian war, the statue remained stuck in Germany until 1871.

The statue didn’t arrive in New York City until July 2nd, 1871. At that time, the City administration was in the hands of William “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Ring, who, among other things, mismanaged Central Park. The corrupt Tweed administration was defeated during the municipal election in 1872, in part because a commission chaired by Emma’s brother, Henry Stebbins, had publicly enumerated and denounced Tweed’s misdeeds. Tweed’s thefts left the public coffers in shambles and to restore them the comptroller of New York City, Andrew Green, drastically cut spending, including spending for Central Park. That is probably why the inauguration of the Bethesda Fountain was a very low profile event.

The inauguration took place on May 31, 1873, “without ceremony, without even any spoken words of introduction by a Commissioner, and with a simplicity that it was not possible to attenuate,” wrote the New York Herald. There was only a little music played by a band. The spectators were mostly Americans of German descent, entire families, flocking not so much for the Angel itself as for their pride in the work of the Royal Munich Foundry.

For the New York Times the Angel was a great disappointment: “From a rear view the figure resembles a servant girl executing a polka pas seul in the privacy of the back kitchen; from the front it looks like a naughty girl jumping over stepping-stones, while the wind drives back the voluminous folds of her hundred petticoats, which, however, are so diaphanous in texture as to clearly reveal the form. The head is distinctly a male head, of a classical commonplace, meaningless beauty, the breasts are feminine, the rest of the body is in part male and in part female.” The article closes with a message that seems actually paid for by the American foundry lobby: The casting of the bronze Angel made in Munich is “infinitely inferior” to that of the Shakespeare statue made by a Philadelphia foundry. It sounds like the slogan “Buy American” that is popular now!

Fortunately, other newspapers and magazines loved Emma’s Angel. The New York Evening Post wrote that the Angel of the Waters elicits “emotions of delight and admiration.” And the New York Herald—the most influential newspaper at that time, and with the largest circulation—praised the Angel.

Emma was not surprised by the bad reviews. She wrote to a friend: “I confess I dreaded the comments of the press which in this country respects nothing human or divine and is moved by any but celestial influences.” But by this time, she was totally absorbed by caring for Charlotte Cushman, who had been diagnosed with breast cancer in 1869.

Towards the end of her life, Emma Stebbins devoted much of her time and energy to Charlotte Cushman—first caring for her as she battled breast cancer, then writing Cushman’s biography after her death. This seems to have been a terribly painful time for Stebbins, especially since she was in poor health herself, and could not return to her own artistic pursuits. How do you think she viewed her own legacy—as a person and as an artist?

It was indeed a terribly painful time for Stebbins. But towards the end of her life, she tried to find her own dimension by looking to the future, even though lung disease always plagued her. She proposed to her friend and colleague Anne Whitney that they write a book together, in epistolary form, exchanging views on art. Emma wanted to share her approach, explaining that she always tried to resist “the pressure of outside influences,” and felt that the pressure to complete work quickly often harmed the final product. Stebbins wrote Whitney that sculpture as a form was the “saddest of all, because what we do is so imperishable.” She added that if she could write exactly about her experience as an artist, that “would teach many lessons.” Unfortunately the book project didn’t materialize. But from her letters you can understand that she wanted to be remembered as an artist who was true and honest.

I think that Emma gave her sister Mary instructions about her grave in the Green-Wood Cemetery, the Brooklyn cemetery where she is buried. And that gives us a hint about how she viewed her own legacy as a person: a brave woman who remained faithful to her partner all her life, resisting the pressures of family and society. On the simple, small marble headstone you can read: “Love is the fulfilling of the law.” It is part of St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans. The apostle summarizes all of God’s laws in one precept: “Love your neighbor as yourself. Love does no wrong to its neighbor. Therefore, love is the fulfillment of the law.” I believe it’s a way of saying that loving another woman is the fulfillment of the law too.

PHOTO OF THE DAY

“OUR LADY OF NOMAD”

CREDITS

N-Y HISTORICAL SOCIETY

JUDITH BERDY

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment