Thursday, April 10, 2025 – DESIGNING A MODERN BABYLON IMAGED BY HUGH FERRIS

Modern BabylonZiggurat Skyscrapers and Hugh Ferriss’ Retrofuturism

By Eva Miller

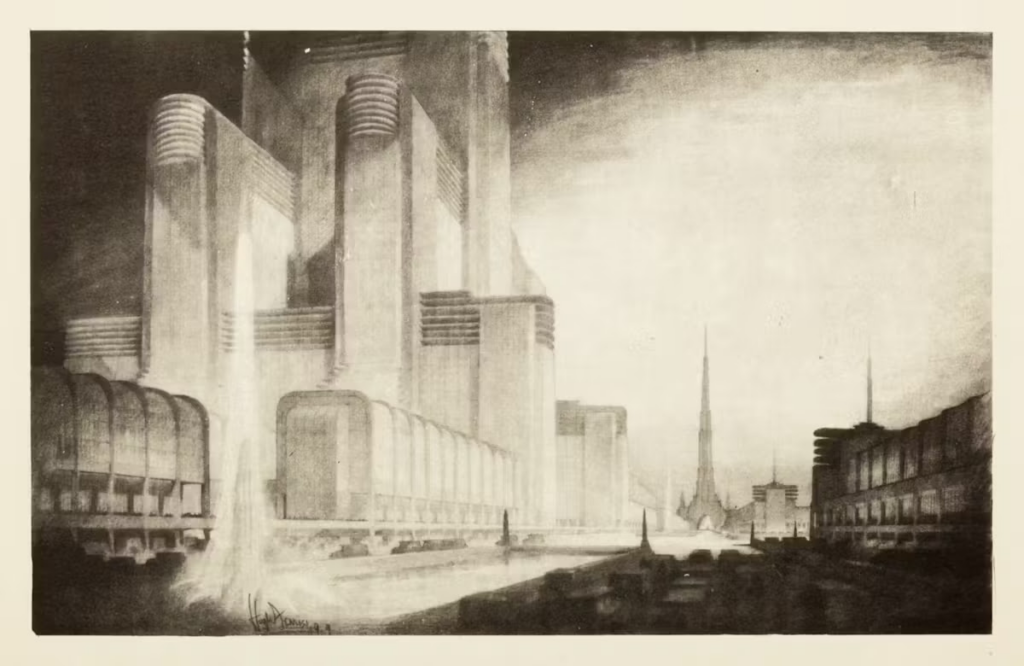

THE PUBLIC DOMAIN REVIEW

Thursday, April 10, 2025

ISSUE #1421

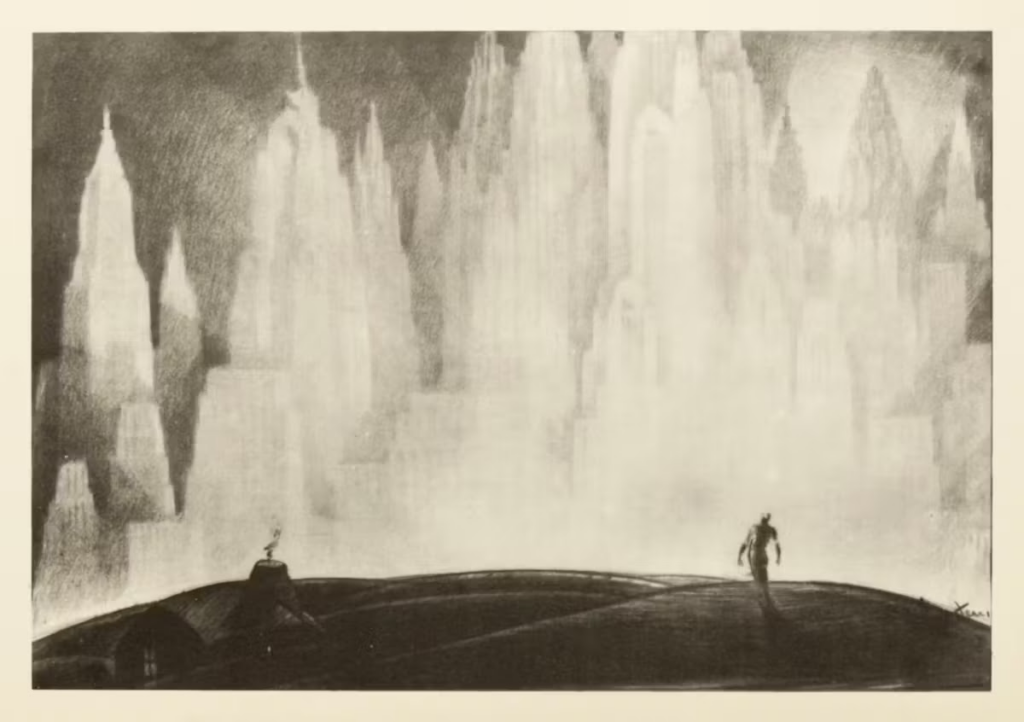

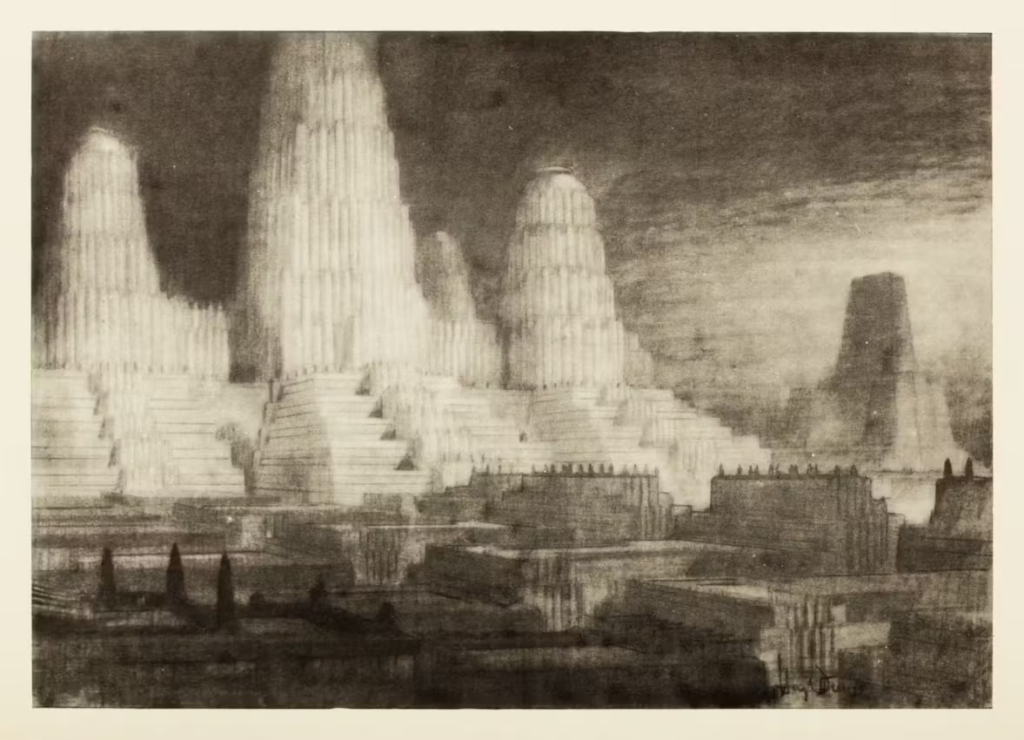

In a dramatic, monochrome rendering in ink and charcoal, a fractal of pyramids and steps regenerates at different scales and angles. Vertiginous towers, the tallest outgrowing the frame, ascend from a base of tiered structures — ziggurats — rising in regular terraces. The roofs of lower blocks are dotted with miniscule trees that echo the larger, manmade shapes around them. They are the only living things visible at this scale, but an accompanying text tells us that this skyline is populated with people, citizens who enjoy the city’s elaborate roof gardens, sun porches, and open-air swimming pools.1

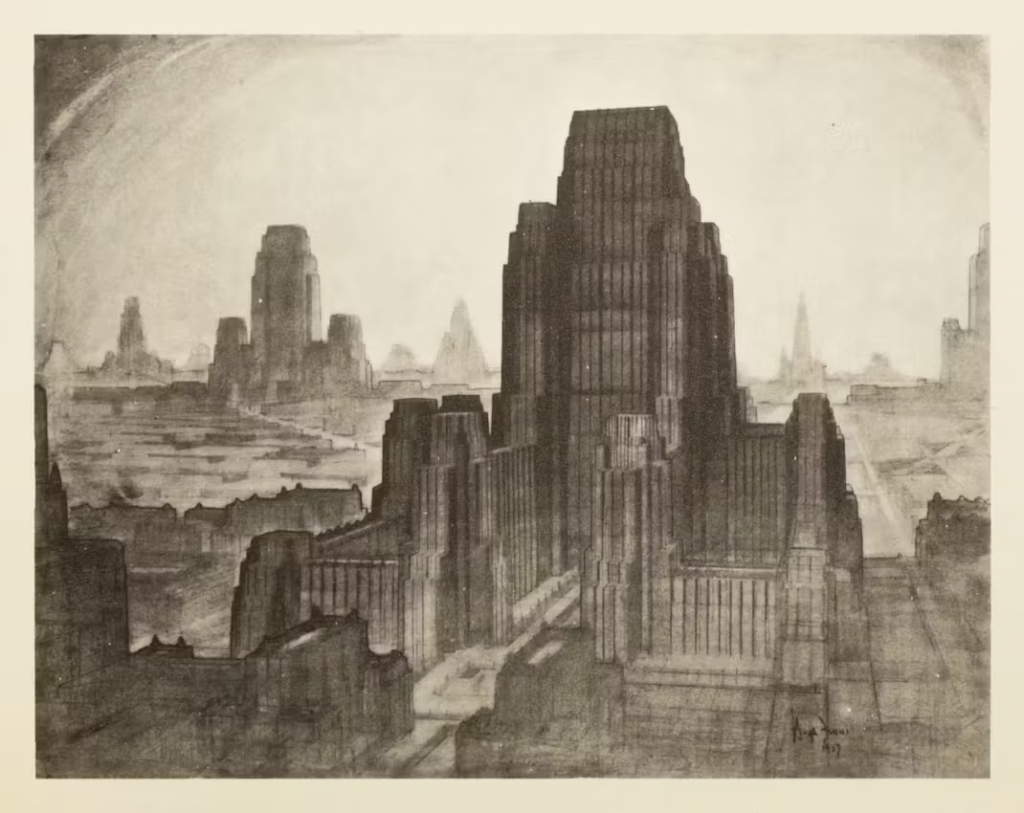

This was how Hugh Ferriss imagined the future of urbanism in his treatise Metropolis of Tomorrow (1929). Born in St. Louis in 1899, Ferris trained as an architect and forged a career for himself in a role for which he invented his own job title: “architectural delineator”, bringing other architects’ projects to life on paper. His portfolio, now held by the Avery Art and Architecture Library at Columbia University, speaks to his proximity to numerous major works of modern architecture and engineering, with renderings of Rockefeller Center, Works Progress Administration infrastructure projects, World’s Fairs, United Nations buildings, and various mysterious, unnamed structures of his own imagination, visions swimming up to us through Ferriss’ dramatic wash of line and shadow.2

Metropolis is a portfolio of Ferriss’ images annotated with reflections on the work he had participated in and the architectural changes he had witnessed during recent decades, when American cities, especially his adopted home of New York, exploded upward. He made modest trend forecasts for the near future: glass, he predicted, would be huge (true); hydroplanes would be everywhere (sadly not). In the final, most memorable section of the book, he sketched a distant City of Tomorrow. This city would be planned along rational lines to maximize human health and spiritual happiness through a three-part plan with districts for art, science, and business, each centered on aesthetically appropriate superblocks.3

In the early twentieth century, architects turned to a newly discovered past to craft novel visions of the future: the ancient history of Mesopotamia. Eva Miller traces how both the mythology of Babel and reconstructions of stepped-pyramid forms influenced skyscraper design, speculative cinema in the 1910s and 20s, and, above all else, the retrofuturist dreams of Hugh Ferriss, architectural delineator extraordinaire.

Ferriss’ dramatic depictions of towering skyscrapers and lofty perspectives became, as media scholar Eric Gordon argues, the means by which “the image of the American urban future in the popular imagination took shape”.4 His futurism anticipated and influenced Norman Bel Geddes, as he created his Futurama for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the Walt Disney Company’s Tomorrowland, TV’s The Jetsons, and numerous other prognostications of the rational planned city, the elevated expressway, and the heliport.5

Yet Ferriss’ forward-looking vision also repeatedly evoked the ancient past. The pyramid skyscraper that he promoted was, in his own description, a “modern ziggurat”, the monumental architectural form of ancient Mesopotamian cities. Centered in modern-day Iraq, Assyria and Babylon were geopolitical superpowers of the first millennium BCE, empires discussed in both biblical and classical traditions which had once been considered lost to the desolating force of time. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, the crumbled remains of ziggurat towers had inspired speculative reconstructions. By the 1920s, German excavations had exposed the well-preserved urban fabric of Babylon’s sixth-century BCE city walls and gates, parts of which were also partially reconstructed in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, looking rather Art Nouveau. Meanwhile, the nearby city of Ur was being excavated by thousands of workers in digs sponsored by the British Museum and the Penn Museum, turning up mass burials of gold-bedecked bodies. These new discoveries stirred those who read about them in the popular press to imagine an antiquity that was also somehow strangely modern: the women’s fashion in the Ur burials led to press jokes about these dead bodies as traces of the original flappers.6

At the time of Ferriss’ Metropolis, a question had bedeviled modern architects for decades: what could be learned from the traditions of the past? Were the great buildings of antiquity, particularly of classical Greece and Rome, eternal blueprints, a standard never to be bettered? Architectural training programs in the US during the early twentieth century suggested this was the case. But increasing numbers of builders worried that the adulation of the past produced dead, stagnant structures, irrelevant to the modern world. Wherever they came down on this matter (and there was a wide middle ground), numerous commentators with different aesthetic preferences could agree on damning random and eclectic historical borrowing — even if they might disagree on what constituted an example of that tendency.

Perhaps no writer treated this historicizing, classicizing eclecticism with more vitriol than the perpetually worked-up Ayn Rand. Her architectural-philosophical melodrama The Fountainhead, published in 1943 but set during the years that Ferriss was writing, was an insightful, if unsubtle, rant against these trends. She castigated architects who “competed on who could steal best, from the oldest source and from the most sources at once”, resulting in “shingled post offices with Doric porticos, brick mansions with iron pediments, lofts made of twelve Parthenons piled on top of one another.” She imagined a benighted public who celebrated a skyscraper which “offered so many columns, pediments, friezes, tripods, gladiators, urns and volutes that it looked as if it had not been built of white marble, but squeezed out of a pastry tube.”7

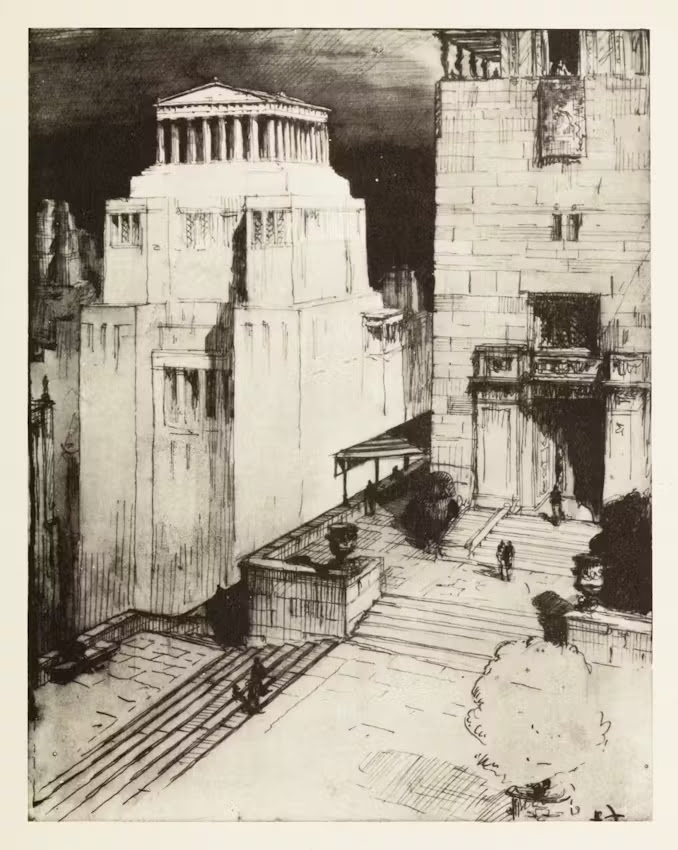

Ferriss was against this kind of inauthenticity too, advocating that modern buildings must follow the diktat of America’s great modernist innovator Louis Sullivan: form ever follows function. Architects of the future, Ferriss assures us, “will dismiss, as sentimentality, the notion that architectural beauty was once and for all delivered to the builders of ancient times. The employment of modern construction to support what are little more than classic or medieval stage sets, they will look upon as, at its most harmless, a minor theatrical art, but no longer as being Architecture”.8 He mocked this kind of “stage set” architecture in an illustration of the “Reversion to Past Styles” for Metropolis. He bemoaned this tendency’s persistence “despite the logical, and sometimes impassioned, pleas of leaders in modern design.” Still, stacks of “the same conventional forms” were appearing, and Ferriss believed it was his “duty to show what would happen if architects continued piling Parthenons upon skyscrapers!”9

THE ABOVE IS A PART OF A LONGER ESSAY ON FERRIS AND THE ZIGGURAT MOVEMENT.

FOR THE CONTINUATION SEE:

https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/modern-babylon-ziggurat-skyscrapers-and-hugh-ferriss-retrofuturism/?utm_source=newsletter

At the time of Ferriss’ Metropolis, a question had bedeviled modern architects for decades: what could be learned from the traditions of the past? Were the great buildings of antiquity, particularly of classical Greece and Rome, eternal blueprints, a standard never to be bettered? Architectural training programs in the US during the early twentieth century suggested this was the case. But increasing numbers of builders worried that the adulation of the past produced dead, stagnant structures, irrelevant to the modern world. Wherever they came down on this matter (and there was a wide middle ground), numerous commentators with different aesthetic preferences could agree on damning random and eclectic historical borrowing — even if they might disagree on what constituted an example of that tendency.

Perhaps no writer treated this historicizing, classicizing eclecticism with more vitriol than the perpetually worked-up Ayn Rand. Her architectural-philosophical melodrama The Fountainhead, published in 1943 but set during the years that Ferriss was writing, was an insightful, if unsubtle, rant against these trends. She castigated architects who “competed on who could steal best, from the oldest source and from the most sources at once”, resulting in “shingled post offices with Doric porticos, brick mansions with iron pediments, lofts made of twelve Parthenons piled on top of one another.” She imagined a benighted public who celebrated a skyscraper which “offered so many columns, pediments, friezes, tripods, gladiators, urns and volutes that it looked as if it had not been built of white marble, but squeezed out of a pastry tube.”7

Ferriss was against this kind of inauthenticity too, advocating that modern buildings must follow the diktat of America’s great modernist innovator Louis Sullivan: form ever follows function. Architects of the future, Ferriss assures us, “will dismiss, as sentimentality, the notion that architectural beauty was once and for all delivered to the builders of ancient times. The employment of modern construction to support what are little more than classic or medieval stage sets, they will look upon as, at its most harmless, a minor theatrical art, but no longer as being Architecture”.8 He mocked this kind of “stage set” architecture in an illustration of the “Reversion to Past Styles” for Metropolis. He bemoaned this tendency’s persistence “despite the logical, and sometimes impassioned, pleas of leaders in modern design.” Still, stacks of “the same conventional forms” were appearing, and Ferriss believed it was his “duty to show what would happen if architects continued piling Parthenons upon skyscrapers!”9

THE ABOVE IS A PART OF A LONGER ESSAY ON FERRIS AND THE ZIGGURAT MOVEMENT.

FOR THE CONTINUATION SEE:

https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/modern-babylon-ziggurat-skyscrapers-and-hugh-ferriss-retrofuturism/?utm_source=newsletter

PHOTOS OF THE DAY

THE DEMOLITION OF THE SYMBOLIC

GLASS ATRIUM OF THE 540 EASTWOOD BUILDING

C&C MANAGEMENT IS DESTROYING THE SYMBOLIC

FACADE WITH NO COMMENT OR INPUT FROM

THE PRESEVATION WORLD OR THE COMMUNITY.

CREDITS

Eva Miller is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at UCL History whose research explores how modern scholars and artists have conceived of the ancient past and theorized the importance of “origins”. She is the author of Early Civilization and the American Modern: Images of Middle Eastern Origins in the United States, 1893–1939 (UCL Press 2024) and editor (with G. Crouzet) of Finding Antiquity, Making the Modern Middle East: Archaeology, Empires, Nations (Bloomsbury 2025). Among other areas, she has worked on self-Orientalising Jewish art, cryptozoological investigations of living dinosaurs attested in ancient Babylonian artefacts, anthropological theories on the evolution of languages and writing, and the role of art in science museums. She originally trained as an Assyriologist, earning her doctorate from the University of Oxford in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies.

The text of this essay is published under a CC BY-SA license, see here for details.

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment