Wednesday, April 30, 2025 – WOMEN HAD AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN PRINTING

Elizabeth Glover & The Founding of Harvard University Press

Wednesday, April 30, 2025

NEW YORK ALMANACK

ISSUE #1438

Elizabeth Glover & The Founding of Harvard University Press

April 28, 2025 by Jaap Harskamp

E lizabeth I’s reign in 1558, a desire was expressed that the role and position of the Church of England should be explained. As a consequence, a stream of devotional and exegetical publications designed for Protestant edification flooded the market. Printers gained a prominent place in the process.

From the outset women were active participants in the trade. They looked after the well-being of young apprentices in the shop and worked alongside men as printer’s devils and compositors. They managed the distribution of printed matter, the sale of stationery and kept the books.

A small number of them ran an entire printing shop by themselves. They were mostly widows who continued business after the death of their partners. Although women were restricted from partaking in business (from buying and selling or interacting with local government), widows were exempt from these repressive “coverture” regulations.

The same conditions would apply in New England. It was a widowed Puritan immigrant who initiated the foundation of Harvard University Press.

Press & Pulpit

In 1562 John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury, published Apologia Ecclesiae Anglicanae (The Apology of the Church of England) in response to the demand for clarification. Crucially, an English version was made widely available in translation of the learned Lady Anne Bacon (her father Anthony Cooke had been tutor to King Edward VI).

The author supplied a vindication of the establishment of the English Church by exposing the failings of Roman Catholicism. The document embodied the deep divisions of a polemical age in which politics and religion were inextricably entwined.

Increasingly, English Protestants started to use the printing press in order to disseminate their message and ideology. Printers supplanted preachers; the press replaced the pulpit.

Printing proved to be a double-edged sword. Soon Puritans, separatists, non-conformists and other dissidents also resorted to the press to advance their brands of Protestantism. Their onslaught against the “half” reformed Church of England and its representatives may have been relentless, but it was met with brutal counterattacks.

Authors, printers and booksellers were imprisoned, physically mutilated or worse. Once strict censorship made printing and publishing too dangerous, Puritan radicals turned to presses in the Protestant Netherlands and continued their crusade by smuggling clandestine literature into the country. The same applied to Catholic authors and printers who organized their “mission” from the university town of Louvain in (Catholic) Flemish Brabant.

For Puritans, printing became a major instrument of religious education and reform. Once the “Great Migration” had started in 1620 with the establishment of the Plymouth Plantation, they transported their skills, practices and regulations from England to Massachusetts.

Diatribe of Distrust

Pre-Revolutionary printing in the British colonies was an urban undertaking and largely confined to the seats of local government. The number of printing establishments was therefore never great and the shops were relatively small (one to three presses).

Compared to London which supplied the whole British Empire with printed matter, the output was small. London not only remained the source for most of the books read in America, but it was also a focus for its authors. First generation Puritan ministers such as John Cotton or Thomas Hooker published their writings almost entirely in the capital.

Early printers produced mainly what could be more conveniently produced at home rather than being shipped from England such as local laws, ephemera, pamphlets or almanacs. Large or lengthy works (including novels) were more economical to import. Before 1740, law books were almost the only folios printed in the colonies.

The first colonial press was established in 1639. The “Cambridge Press,” like the William Brewster’s “Pilgrim Press” at Leiden in the Netherlands (between 1617 and 1619), began the publication of religious works without interference from London. But practitioners had other obstacles to overcome. They were dependent on government contracts and their output was regulated by the ruling oligarchy.

Control was strict as the authorities were prone to take offense at any “disagreeable” publication (William Bradford was persecuted in 1692). They distrusted the printed word and feared it would breed schism and sedition – England had set a precedent.

William Berkeley, Charles II’s Royal Governor of Virginia in 1671, attacked both public education and printing, arguing that learning had brought “heresy and sects into the world and printing [had] divulged them.” Berkeley’s diatribe summarized Puritan unease about the free flow of ideas.

Up until the eighteenth century little changed in the actual technology of the printing process. The slow evolution of the press gave way to rapid expansion in the 1720s and 30s.

The rise of the newspaper altered the socio-economic position of colonial printers as commercial demand for printed matter increased. It was only then that the city of New York manifested itself as a future printing powerhouse.

The Widow Franklin

Early colonial printers were mainly male immigrants from England. The Franklin brothers may have been American-born, but they received their training in English printing shops. The role of immigrant women in general and in the trade in particular has been persistently underestimated.

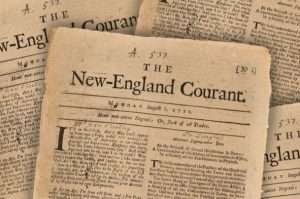

In 1721, Benjamin Franklin’s elder brother James became the Boston-based printer of the New England Courant, one of the first independent American newspapers. In 1727, he and his wife Ann Smith-James moved to Newport, Rhode Island, and opened the colony’s first print shop.

Ann was fully engaged in the undertaking, she knew how to set type and operate the press. In 1732, the couple started the Rhode-Island Gazette, James acting as its editor and Ann taking on the role of assistant printer.

James died in February 1735. With her know-how of the printing process and her extensive experience of running the firm, Ann was more than capable of continuing the business.

As Franklin’s widow, she was granted the legal right of forming and dissolving partnerships, pursuing contracts and expanding the firm’s commitments. Within a year of her husband’s death, Ann secured the lucrative position of “Colony Printer.”

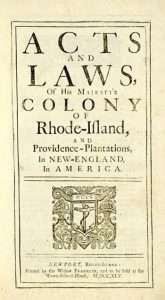

Working for the Rhode Island Assembly, she was tasked with producing all legislative and official documents (she printed the Colony’s Charter granted by Charles II). Her publications carried the standard imprint “Newport, Printed by the Widow Franklin.”

In addition to printing pamphlets and sermons, she also published a newspaper titled The Newport Mercury. In 1748, her son Jemmy became a partner in his mother’s printing house. After Ann’s death in 1763, the company continued to produce books, almanacs, pamphlets and legal documents.

The Franklin succession was a common phenomenon in the trade. It occurred continuously in Europe and was likewise repeated in the American Colonies where female professionals stood in the vanguard of the trade.

It was Mary Katherine Goddard (1738-1816) in Baltimore who printed the first signed edition of the Declaration of Independence. America’s first printing house was also run by a widowed woman.

The Glovers

In 1624 Reverend Joseph Glover took on the position as Rector of St Nicholas Church, Sutton (about fifteen miles south of London), where he arrived with his young wife Sarah Owfield who brought with her a generous dowry. The clergyman came from a prosperous family too and the couple lived in stylish comfort until Sarah’s early death.

In 1630 Glover remarried Elizabeth Harris, daughter of the Reverend Nathaniel Harris, a prominent figure in ecclesiastical circles. During the first six years of their marriage, Joseph continued to serve the Sutton rectory. Elizabeth cared for three stepchildren and had two children herself with Joseph.

Gradually, Glover began questioning his religious loyalty, whilst his interest in Puritan thinking deepened. As a consequence, in 1636 the family had to leave Sutton and began planning a move to New England with the ambition of starting a printing press.

With financial support from friends, Joseph purchased a press, font and other supplies needed to establish a business. In June 1638, he hired Sutton-born locksmith Stephen Daye and three workers to run and maintain the press. Part of that contract included the Glovers financing the journey to New England of Daye and his family.

In the summer that year the John of London, captained by Master George Lamberton, sailed from Hull to Boston. She was one of eight to twelve ships organized by the Reverend Ezekiel Rogers to transport about sixty families from the Yorkshire village of Rowley to New England (they would eventually settle in Rowley, Massachusetts). Colonization of the region was to a large extent determined by the arrival of family groups.

Among the passengers were the Glovers, the Daye family and three assistants. Stowed away in the ship’s hold were a printing press, type, reams of paper, ink and maintenance tools.

During the voyage Joseph died of an illness, probably smallpox, and was buried at sea. Elizabeth was now the sole owner of the printing press and Stephen Daye’s indenture. The ship arrived a few weeks later on the coast of New England.

Crooked Street

When Elizabeth and her children arrived in Cambridge in the fall of 1638, she decided to settle near the town’s college and acquired a large house built by John Haynes (former governor of Massachusetts and the first governor of Connecticut). Once settled, Elizabeth gained approval from local magistrates and elders to establish a printing house.

She purchased a property for Stephen Daye and his family in Crooked Street (later: Holyoke Street) where the printing press was installed in one of the lower rooms. Elizabeth was in charge of the “Cambridge Press,” Stephen Daye acted as manager, while his son Matthew did much of the laborious tasks.

Within the first year of settlement, Stephen and Matthew printed a broadside entitled “The Freeman’s Oath,” the first tract published in North America. Written by John Winthrop, the Oath was taken by every man over the age of twenty who had been a householder for at least six months, making him a freeman of the Corporation and legal citizen of the Massachusetts Bay Company. Apart from the original text penned by Winthrop himself, no copy of this document exists today. The only surviving work is a reprint.

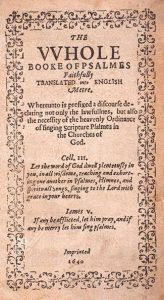

Elizabeth Glover also produced The Whole Booke of Psalmes Faithfully Translated into English Metre, commonly called the “Bay Psalm Book.” It was the first book printed in the Colonies. Although a versatile craftsman, Stephen Daye was not a trained printer; his workers were inexperienced; and his types were poor.

The result of his labors was a crudely printed quarto of 148 leaves. Typographical errors and curiosities of spacing exist throughout the book. Out of the 1,700 copies printed, only eleven are known to have survived, many of them in poor condition.

Harvard: College & Press

Henry Dunster was born in 1609 near Bury, Lancashire. After graduating from Magdalene College, Cambridge, in 1634, he became Curate of Bury Parish Church and was appointed (the third) Master of Bury School. Like many fellow Puritans, he condemned the “corruptions” of both state and church. In the summer of 1640, he left Lancashire for New England.

Dunster had lived for only three weeks in Massachusetts when he was appointed President of Harvard College (later Harvard University). His selection remains somewhat of a mystery. He was barely known to the authorities; there was no evidence of his qualities as a teacher or administrator; he held a master’s degree, but had never published. In spite of initial uncertainties, he was later credited with rescuing the fledgling institution from collapse and laying the groundwork for its future development.

Elizabeth Glover and Henry Dunster met and shortly after were married (June 1641). He became co-owner of her printing press. She died two years later, leaving in his care five stepchildren and the ownership of a publishing house.

He removed the press to the newly erected President’s residence in Harvard Yard. Here the Laws and Liberties of Massachusetts were printed in 1648, followed a year later by the Cambridge Platform (a standard for Massachusetts Bay’s religion until the time of the American Revolution).

Henry dismissed Stephen Daye and put his son in charge of the Press, but the output declined sharply. With the premature death of Matthew Daye in 1649, Dunster appointed Samuel Green and, in 1651, commissioned a reprint the Bay Psalm Book as this text remained in demand throughout the seventeenth century.

When Henry Dunster died in 1654, the printing press was gifted to Harvard College. Harvard University Press as we know it today was founded in January 1913.

Is there a justifiable case for Britain to claim back stewardship of Harvard University in order to safeguard its academic independence?

PHOTO OF THE DAY

STILL A WONDERFUL SITE-

DRIVING OVER THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: U.S. stamp commemorating the 300th anniversary of printing in colonial America; The New-England Courant, August 7, 1721, published in Boston by James and Ann Franklin; Acts and Laws … of Rhode Island; Newport, Printed by the Widow Franklin, 1745; Title page of the first book printed in North America The Whole Booke of Psalmes, 1640 (The Rosenbach Museum and Library, Philadelphia); and Harvard University Press logo, 1925.

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment