Tuesday, May 13, 2025 – THE HEIGHT OF STYLE FOR ALL WOMEN IN THE 1880–1890’S

The Stylish Shirtwaist

THE NEW-YORK HISTORICAL BLOG

Keren Ben-Horin

Women at the Center

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

ISSUE #1447

Unidentified maker. Shirtwaist, 1890–1900. Cotton, needlepoint lace. The New York Historical, Z.1317

Between the 1860s and 1910s, the shirtwaist was a wardrobe essential, as popular a women’s garment as a pair of jeans are today. As a result, shirtwaists are an object of inquiry for many Center for Women’s History projects.

This tailored bodice, worn tucked into a skirt, was a democratic equalizer donned by American women of all classes and races. It was among the first women’s clothing to be available ready-made in an endless variety of fabrics, styles, and price points. The wide variety of shirtwaist styles (sometimes called simply waists) made them a wardrobe staple, especially for younger women. Shirtwaists could be tailored with starched collars and cuffs in a masculine style or femininely soft and lightweight, with lace and needlepoint inserts like the example included in our 2023–24 exhibition Women’s Work. These popular garments could be paired with a light, matching skirt for a summer afternoon outing, or paired with a dark skirt for a woman working as a clerk, a salesperson, a teacher, a garment worker, or—as pictured here—a public health official.

They are literally thousands of doors lining the streets of Paris. Some are very simple doors, others are extravagant works of art. The styles of these doors tell about the history of Paris. As you walk across the 20 arrondissements of Paris, you will discover Gothic, Renaissance, Haussmann and Art Nouveau door styles. It is up to you to take the time to look for little details of these Paris’ most beautiful doors: mascarons, statues, bas-reliefs, gold-leaves, handles…

Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870–1942), photographer. Dr. Josephine Baker, head of the Child Hygiene Dept. of the Dept. of Health of C[it]y of NY, 1917–19. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

Shirtwaists could also be worn for leisure activities and sports, such as bicycling, sailing, tennis, and golf, that both pushed the boundaries of “acceptable” feminine behavior, and required clothes that allowed a full range of motion. Along with slightly shorter hemlines, many of these athletic outfits incorporated ties, tailored jackets, and shirtwaists. Sometimes they were paired with bloomers, the ballooning undergarments adopted by that time period as gym clothes in women’s colleges around the country.

Burr McIntosh (1862–1942), photographer. Woman with golf clubs, ca. 1900–10. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

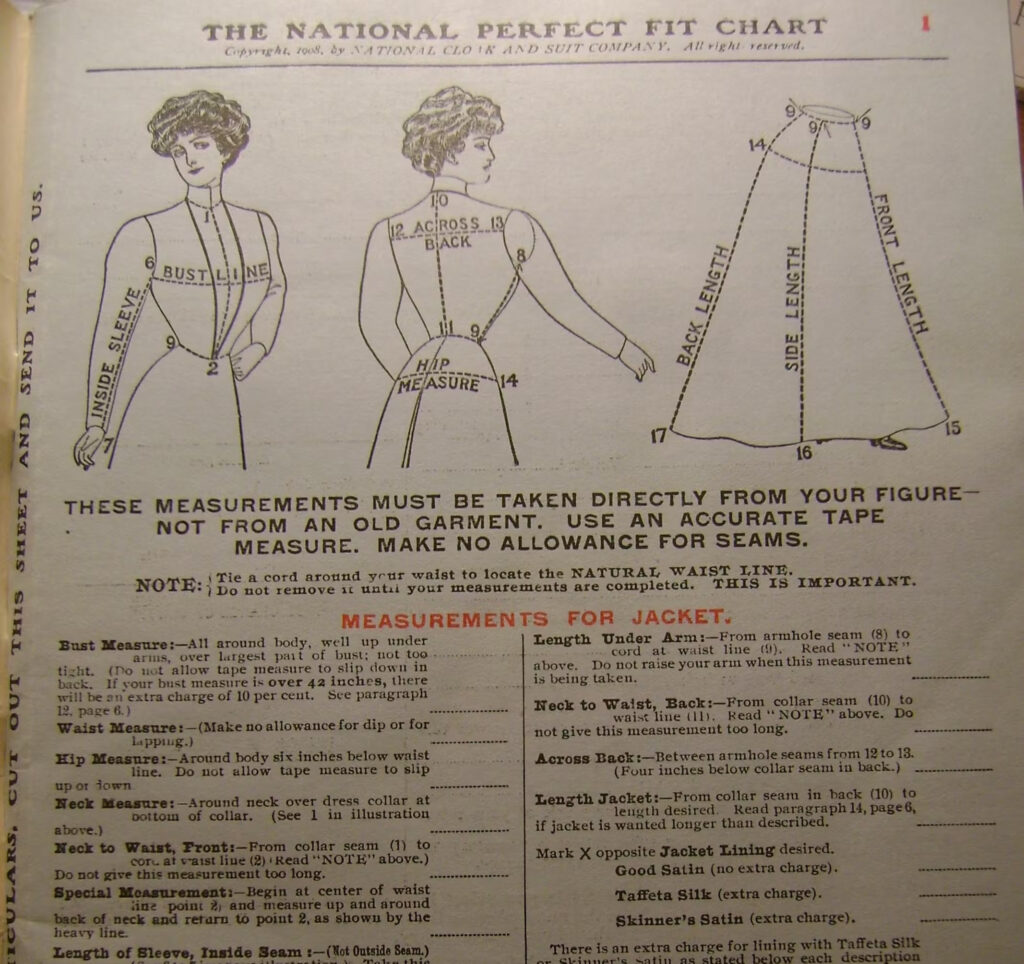

The shirtwaist in The New York Historical’s collection was most likely sewn at home, perhaps using a paper pattern purchased from the several home-sewing magazines that were available during that time period. Women’s magazines of the time often included detailed descriptions of how to construct shirtwaists at home using a domestic sewing machine: a mid-19th century innovation that helped reduce the time-consuming task of dressing the family while increasing the number of clothes per person. For our Women’s Work exhibition, we commissioned dress historian and living-history specialist Kenna Libes to create a matching skirt that would closely illustrate how the shirtwaist in our collection would have been worn. She used historical patterns to recreate the skirt from lightweight linen, closely matching the one used to make the original garment

National Cloak and Suit Company. New York Fashions, 1908. Bella C. Landauer Collection of Business and Advertising Ephemera, Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

By the last quarter of the 19th century, shirtwaists were predominantly manufactured by low-paid women toiling in Manhattan’s sweatshops. Garment manufacturing labor was historically divided by gender and dictated by the type of garment. Men traditionally worked with finer, high-quality woolens requiring careful tailoring, while women made cheaper, looser-fitting garments, especially those worn by women themselves. But, by the mid- to late 19th century, these roles shifted. Immigrant men increasingly occupied jobs previously held by women and produced a greater number of women’s clothes in a task system: instead of making a garment from start to finish, each worker was in charge of one step in the manufacturing process. That also meant that skilled tailors who could fashion a garment from start to finish were increasingly unnecessary, replaced by low-paid workers, predominantly Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. The production of shirtwaists, children’s dresses, and robes became known as the “women’s industries,” because 95 percent of the workforce were young, unmarried women.

Unidentified photographer. Group of striking women — shirtwaist workers, New York City, 1909. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Ironically, many of the women toiling in New York’s massive factories, making ready-made shirtwaists for American women of every walk of life, were themselves wearing shirtwaists. In 1909 and 1910, thousands of garment workers left their sewing machines and marched the streets of Manhattan demanding better pay and better working conditions. Known as the “Shirtwaist Strikes” or the “Uprising of the 20,000,” it brought out a mass of demonstrators in their finest: white shirtwaists, paired with serious looking dark skirts, and fashionable hats that sent the message that their labor was respectable and worthy of a living wage, a clean and healthy environment, and a workday that did not extend from dawn to sunset. Sadly, despite the strides they made in 1909 and 1910, it took a horrifying disaster to bring meaningful change: in 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire claimed the life of 146 garment workers, mostly young Jewish immigrant women, and exposed the human cost of fashionable, affordable clothing. You can read more about the fire that claimed so many young lives in this post from our archives.

Frederick Hugh Smyth (1878-1949), photographer. Triangle Waist Co. Factory Fire, Washington Place & Greene Street, 1911. Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, The New York Historical

Don’t miss out on a chance to learn more about shirtwaists: visit Real Clothes, Real Lives: 200 Years of What Women Wore, an exhibition of garments from the Smith College Historic Clothing Collection, on view in our Joyce B. Cowin Women’s History Gallery until June 22, 2025.

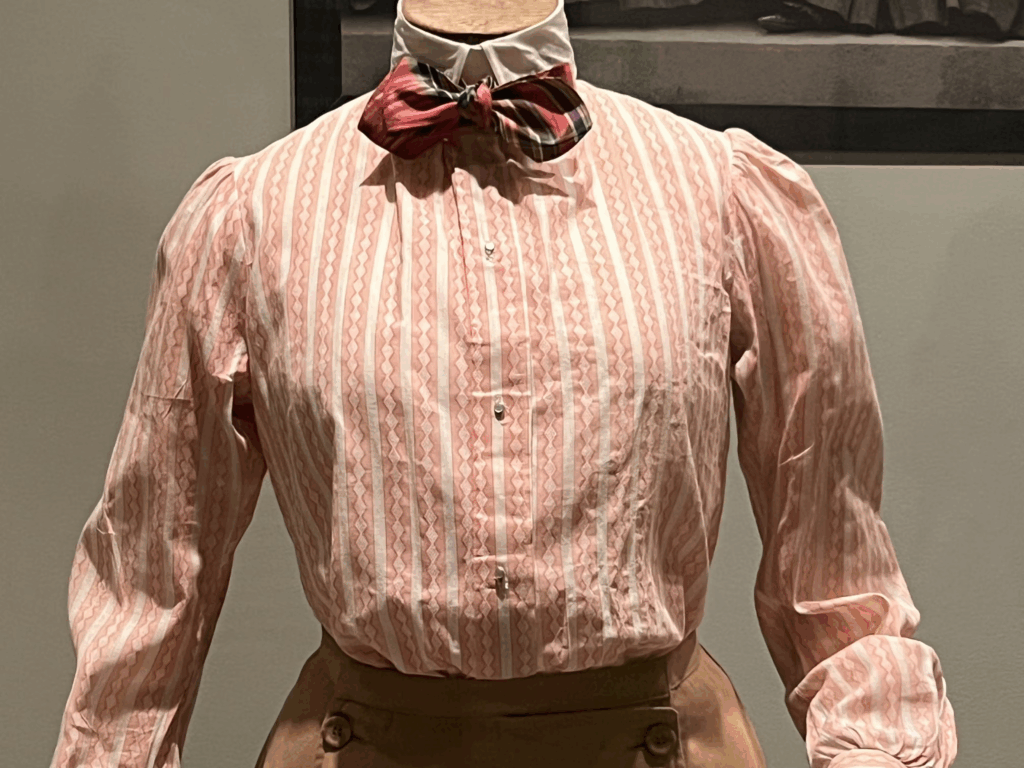

Unidentified maker. Pink striped shirtwaist, ca. 1902–03. Cotton, mother-of-pearl studs. Smith College Historic Clothing Collection, SCHCC 2015.1.38

PHOTO OF THE DAY

MANHATTAN ABLOOM FROM CORNELL TECH

CREDITS

NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY BLOG

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment