Wednesday, May 14, 2025 – A WONDERFUL COLLECTION DONATED TO THE N-Y HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Scenes of New York City: The Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld Collection

THE NEW-YORK HISTORICAL

Wednesday, May 14, 2025

ISSUE #1448

This collection exudes New York. Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld have amassed a stunning array of works honoring their hometown, from its bustling harbors to its Harlem diners, Village speakeasies, sleek skyscrapers, and gritty streetscapes. Their promised gift to the New-York Historical Society invigorates the Museum’s 20th- and 21st-century holdings and amplifies the story of a place at once enthralling, mystifying, and inspiring.

Art by Keith Haring, Jacob Lawrence, Andy Warhol, Giorgio de Chirico, and Georgia O’Keeffe, among others, brings the city to life. The 130 paintings, sculptures, prints, and drawings in the collection spotlight New York-centric movements like Abstract Expressionism and Pop, probe Gotham’s layered past, and trace the rhythms of the metropolis and its daily life.

To match the multiple facets captured in this portrait of the city, the New-York Historical Society invited multiple New Yorkers to respond to select objects in the collection. Their commentaries appear under the heading “COMMUNITY VOICE.”

Manhattan with Roosevelt Island Removed

1978

Cut black and white photograph

15 7/8 x 15 7/8 in.

Promised gift of Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld, Scenes of New York City

IL2021.51.102

Solomon LeWitt, known as Sol, executed Manhattan with Roosevelt Island Removed the year the Conceptual artist received a major retrospective at MoMA. It belongs to a series of works on paper (1967–80) that explore the different ways that LeWitt could alter black-and-white aerial photographs and maps. The work is also part of a group of torn-, folded-, and cut-paper compositions that LeWitt termed “hundred dollar drawings” because he wanted them to be sold for $100 in perpetuity—a rock-bottom price for a one-of-a-kind artwork at the time. For the series, LeWitt excised geometrical shapes or areas from satellite photographs or cartographic maps of recognizable cities, among them New York (as in this work), Chicago, Amsterdam, London, and Florence, leaving empty spaces. The 1978 MoMA catalogue describes each as a “cut paper drawing.” They demonstrate LeWitt’s conceptual explorations of different markmaking systems and embody his resistance to the commodification of art. The action of cutting away a part of the image liberates the map or photograph from its producer and its original purpose, he stated, because it becomes a different entity. The action also induces sensations of dislocation as geography is disembodied. In addition, LeWitt’s titles are intended as instructions to anyone interested in repeating his procedure—in keeping with the artist’s decommodification of art and what one critic calls his “wink at any belief in maps’ reliability.” A son of Jewish immigrants from Russia, LeWitt visited Hartford, Connecticut’s Wadsworth Atheneum as a child, which sparked his interest in art; he would develop into a major figure in the vanguard of later twentieth-century art. As a youth, he was employed as a graphic designer at Seventeen magazine and in the office of the architect I.M. Pei. In 1960, he took a low-level job at MoMA, and this and his discovery of Eadweard Muybridge’s serial photographs of locomotion clinched his decision to be an artist. Prolific in a wide range of media—drawing, printmaking, photography, painting, installation, and artist’s books—LeWitt helped summarize Minimalism and Conceptualism with his 1969 credo: “[T]he idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” The artist and others denied the materiality of New York School painting, the quickly understood logos of Pop Art, and the swift commercial success of both. LeWitt reduced art to its geometric essentials—an open cube as a modular unit—which he multiplied into “structures” (a term he preferred to “sculptures”) that filled their settings. The cubes themselves were empty spaces; only their outlines were physical. The next step in this reductivism occurred in 1968, when he began executing drawings directly on the wall, and then to his providing drawing instructions to be executed by assistants. LeWitt’s radical step transformed the act of drawing—yet without losing beauty. In fact, the artist soon added full color and environmental scale, as he expanded his diverse drawings from floor to ceiling and around doors, while upending conventional relationships between art and architecture. Likewise, his Manhattan with Roosevelt Island Removed defies expectations of what aerial photographs and maps do. His simple excision turns a black-andwhite sign system into an object—an altered glossy photograph— and displays the artist’s power over a potent emblem of New York. Conceptual Art for LeWitt was neither mathematical nor intellectual but intuitive. That he was a major figure in the art world of the 1960s and 1970s is not surprising. COMMUNITY VOICE The excising of Roosevelt (formerly Blackwell’s) Island makes me wonder whether LeWitt is making a statement about its dark history as a hub for institutions housing the sick, poor, imprisoned, and mentally ill. Does the erasure represent a call for reforming these institutions and a more humane treatment of their residents? Steve Hanon President, The New York Map Society

ClassificationsDRAWINGS

Collections

- Scenes of New York City: The Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld Collection

- Discover More

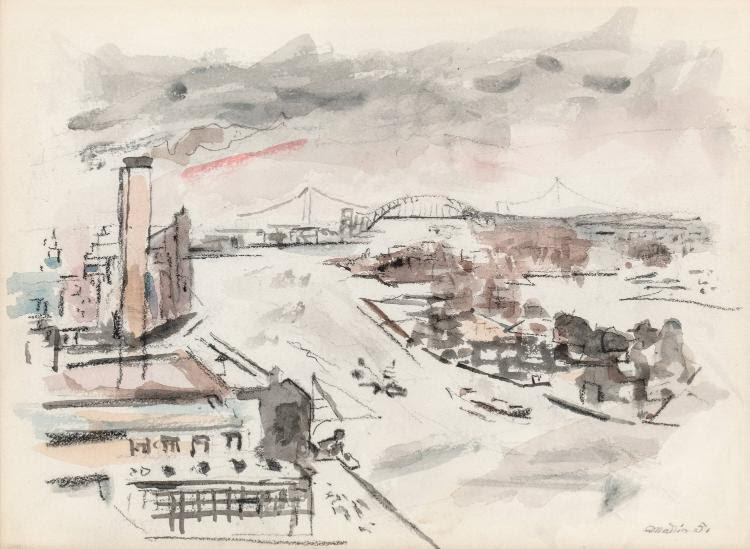

View of the East River Looking North with the Hell Gate and Triborough Bridges from Manhattan

1951

Watercolor and black crayon on paper

Unframed: 8 1/2 × 11 1/2 in. (21.6 × 29.2 cm)

Framed: 14 1/2 × 17 1/2 in. (36.8 × 44.5 cm)

Promised gift of Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld, Scenes of New York City

IL2021.51.18

This watercolor has a provenance from Edith Halpert’s pioneering Downtown Gallery, the first commercial art space in Greenwich Village that promoted avant-garde art. By 1945, the gallery had moved to 32 East Fifty-first Street, where the John Marin Room, operated by John Marin Jr., opened in 1950. An early American modernist, Marin is known for his abstract landscapes and freely painted watercolors. Together, the two works reveal the artist’s stylistic development between 1936 and 1951 toward greater freedom and breadth of execution and, above all, toward mastery of the medium. View of the East River Looking North belongs to a series of small watercolors from 1951 entitled “From New York Hospital,” which the artist produced from his sickbed. Looking out of his window while lying gravely ill, he began using a syringe to draw lines. In 1912, New York Hospital became affiliated with the Cornell University Medical College and moved to York Avenue between East Sixty-sixth and Sixty-seventh streets; today, after another merger, it is known as New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Unlike most of the works in Marin’s series—views looking downtown featuring more southern bridges across the East River—this watercolor has an uptown vista toward the arched Hell Gate Bridge (1912–16) and the Triborough Bridge (1936), renamed the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge. Marin created this limpid cityscape with freely applied black brushstrokes that are similar to strokes of Chinese calligraphy, and he varied the width of the layers of translucent washes that resemble pure staining. He also left large areas of bare paper—known as “the reserve”—to create much of the atmospheric sky and the East River’s water: both elements are made mutable with transient effects. Marin’s ability to render water benefited from the many studies he had made of it during summers in Maine. “In painting water make the hand move the way the water moves,” the artist advised in a letter of 1933. In his youth, Marin had wanted to become an architect, and his fascination with architecture, which is evident in these watercolors, became a constant theme in his works. After attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia and the Art Students League in New York, like many of his contemporaries Marin went to Europe, and over the next six years obtained his first exposure to modern art. There, he mastered watercolor media and endowed his works with the sense of avant-garde freedom that became one of his hallmarks and allied him with like-minded figures in the art world. Introduced by the photographer Edward Steichen to Alfred Stieglitz, Marin was given his first one-person exhibition at Stieglitz’s avant-garde 291 Gallery in 1909. Four years later, Marin exhibited five watercolors in the landmark 1913 Armory Show. Then, in 1938, his art enjoyed a retrospective at MoMA, establishing him as a leading modernist. Among the first American artists to make abstract paintings, Marin is often credited with influencing the Abstract Expressionists.

ClassificationsDRAWINGS

Collections

- Scenes of New York City: The Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld Collection

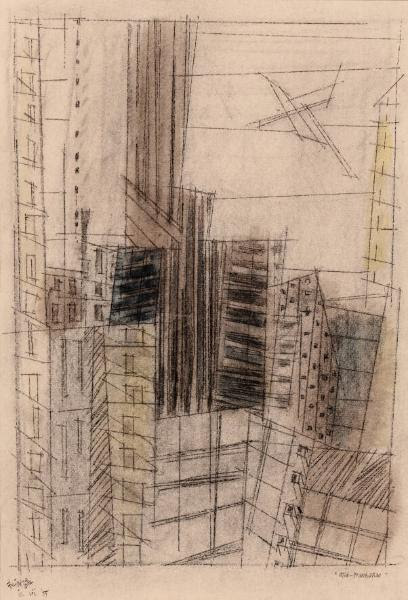

Mid Manhattan

1955

Charcoal, black ink, and watercolor on beige paper

Unframed: 19 1/4 × 12 1/4 in. (48.9 × 31.1 cm)

Framed: 24 1/4 × 25 in. (61.6 × 63.5 cm)

Promised gift of Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld, Scenes of New York City

IL2021.51.19

Mid-Manhattan is Lyonel Feininger’s elegantly delineated ode to the vertical landscape of his birth city, which he executed a year before his death. The sheet’s distinguished provenance can be traced to the artist’s estate. Feininger is best known as a German-American painter and member of the Bauhaus (operative 1919–33), the German school of art and architecture famous for its modern approach to design. Its mission was to unite the fine and applied arts, the aesthetic and the functional, and to reconcile mass production with individual artistic vision. Architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, appointed Feininger to head its printmaking workshop. Not only did the latter teach at the Bauhaus with his friends Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, but he also designed the expressionistic woodcut cover for its 1919 manifesto, whose aspirational forms are allied with those of Mid-Manhattan. His allegiance to Bauhaus ideals of crystalline architecture is evident in the Hirschfeld Collection promised gift, as is his early experience as a draftsman and a master of expressive, often witty linear invention. In fact, Feininger‘s teenage career as a cartoonist in the United States and Germany was so successful that he only began to paint at the age of thirty-six. The artist’s foundational years in Germany inform Mid-Manhattan. A child of professional musicians who instilled in him a love of music, Feininger was also a pianist and composer. At the age of sixteen, he began studying at the Leipzig Music Conservatory, but his interest in drawing led him to transfer to the Hamburg School of Art and soon afterward to the Royal Academy of Arts in Berlin. He exhibited drawings at the Berlin Secession (1901–03), supporting himself by producing caricatures and cartoons, which allowed him to experiment with shorthand styles and abstraction. Although Feininger is not well known for his work in comics, his strips play an important role in the history of comic art. Becoming a member of the Berlin Secession in 1909, Feininger also associated with avowedly Expressionist groups, such as Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). During trips to Paris, he was drawn to Cubism, especially the faceted planes of color in the works of Orphist Robert Delaunay. Like Delaunay, Feininger frequently focused on the urban landscape and its perceptually dazzling glass-walled buildings, as in the interpenetrating geometries of his ethereal Mid-Manhattan. When the National Socialist party came into power in 1933, it closed the Bauhaus and declared Feininger’s work “degenerate art,” exhibiting it in the 1937 exhibition of the same name, Entartete Kunst, the Nazis’ term for the spectrum of modern art. Before that exhibition in Munich, Feininger had escaped to the U.S., as had such Bauhaus leaders as Gropius and Anni and Joseph Albers, moving permanently in 1938 to a vastly changed New York City, which enthralled him until the end of his life. COMMUNITY VOICE Mid-Manhattan reminds me of the wonderful, unpredictable juxtaposition of buildings that makes New York’s skyline unique. I see both modern buildings and older buildings in this drawing. Feininger had been at the Bauhaus in Germany, and the architectural descendants of that movement were just making it to the United States when he drew this. I wonder if he was drawing what he saw out his window or what he imagined New York’s future to be. Frank Mahan Architect at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

ClassificationsDRAWINGS

Collections

- Scenes of New York City: The Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld Collection

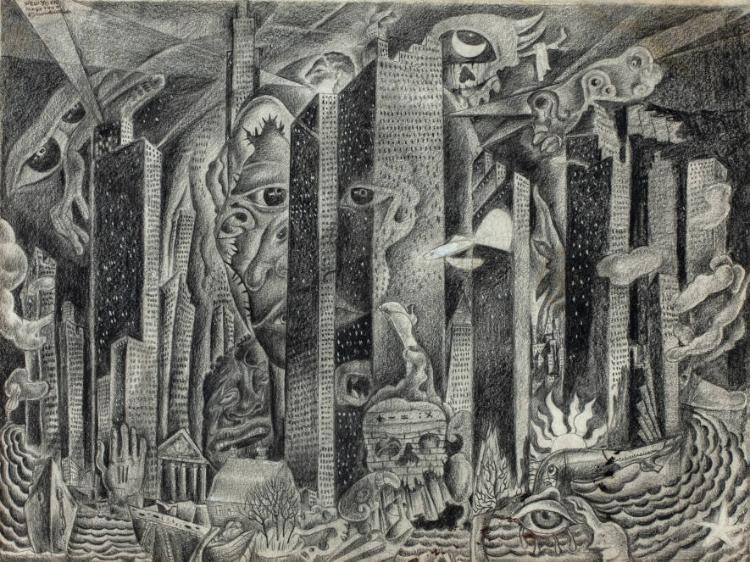

New York

1940

Graphite, black chalk, black ink, watercolor, and white heightening on paper

Unframed: 17 3/4 × 23 7/8 in. (45.1 × 60.6 cm)

Framed: 24 1/2 × 30 in. (62.2 × 76.2 cm)

Promised gift of Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld, Scenes of New York City

IL2021.51.48

Roberto Montenegro’s apocalyptic cityscape is populated by surreal creatures that morph into composite forms, and swim with fish in an aqueous atmosphere interpenetrating the geometric shapes of skyscrapers and earlier building types. Under a watchful eye with a crescent moon, this hallucinatory scene presents, among other things, a weeping eye that sprouts a female leg wearing high heels and a building in the shape of a skull. Winds whip disembodied faces around a wasteland that distantly evokes the southern tip of Manhattan surrounded by the sea. The Mexican artist may have included a self-portrait to the left of center in this personal vision, which is more than a disquieting visual nightmare, and today may seem prophetic. He has transfigured reality and created an oneiric world with its own puzzling laws and an iconography that remains too arcane to decipher completely. Although he claimed to be a “subrealist” rather than a Surrealist, Montenegro often mixed two elements: folklore and fantasy. New York reveals the artist’s awareness of Maurits Cornelis Escher, the Dutch graphic artist and illustrator, whose work showcases mathematical operations, impossible juxtapositions of objects, and explorations of reflections and infinity. Escher’s example may have encouraged Montenegro’s success as an illustrator. When the Mexican artist delineated this highly finished scene, he also must have known Pablo Picasso’s monochromatic painting Guernica (1937). In 1940, the Spaniard’s watershed antiwar statement was politically and artistically topical. During the Spanish Civil War, Guernica was exhibited in the Spanish Republican Pavilion at the 1937 Internationa; Expostion in Paris, and elsewhere, to raise money for war relief. At nearly two feet wide—unusual for a drawing—New York in scale and subject may testify to Montenegro’s experience as a muralist. In fact, he was one of the first artists involved in the Mexican muralist movement after the Mexican Revolution (ca. 1910–20). One of his classmates at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City was Diego Rivera, who helped establish the movement and became one of its leaders. Montenegro continued his artistic education in Europe, first in Spain and then in Paris (1907–10), where he met the Cubists Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris. When World War I broke out in 1914, he moved to Mallorca, painted his first mural, and earned his living as a fisherman—an experience reflected in New York. After moving back to Mexico permanently in 1921, he painted his most important murals at the former monastery and school of San Pedro y San Pablo in Mexico City, the church of which is now the Museo de la luz. Even though he did not consider himself a Surrealist, his works fuse diverse realities, seen especially in his beguiling self-portraits and portrayals of his colleagues and friends, including Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Montenegro’s passion for all things Mexican was manifested in his promotion of Mexican folk art and artisans through books and exhibitions in Mexico and the United States.

ClassificationsDRAWINGS

Collections

- Scenes of New York City: The Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld Collection

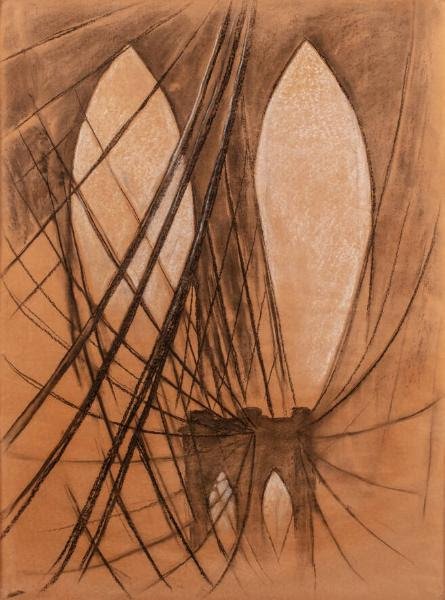

Study for “Brooklyn Bridge”

1949

Charcoal and black and white chalk on paper

Unframed: 39 7/8 × 29 1/2 in. (101.3 × 74.9 cm)

Framed: 47 1/8 × 36 3/4 × 2 1/4 in. (119.7 × 93.3 × 5.7 cm)

Promised gift of Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld, Scenes of New York City

IL2021.51.49

Georgia O’Keeffe’s powerful is dynamic and emotional. It has an eminent provenance from its original owner Doris Bry—O’Keeffe’s agent, confidante, and the noted scholar of Alfred Stieglitz, the artist’s husband. Bry acquired the large sheet directly from the artist in 1978, underlining that O’Keeffe valued it, keeping it with her for nearly three decades. That same year, O’Keeffe sold Bry another smaller, descriptive graphite sketch of one of the bridge’s towers with only a few cables delineated, which was likely O’Keeffe’s initial study. In the large drawing the artist placed the viewer inside rather than outside the bridge’s dynamic heart, its arches seemingly illuminated in white chalk with the cables swinging freely. O’Keeffe repeated the other tower with its crenelations, as in her initial sketch, in a smaller scale—either in the perspectival distance or like a footnote in a transparent experience of the bridge with two views telescoped together. This juxtaposition creates a simultaneity that endows the sheet with a complex and mysterious power. The artist loved to draw in friable charcoal, as well as in graphite, admiring its softness, boldness, and its ability to create threedimensional forms by smudging. She drew a few other bridges—among them two graphite sketches of the Triborough Bridge in New York (1936), and an unidentified bridge (1901–02)—but none have the immersive power of the Hirschfeld Collection sheet. The longest suspension bridge in the world when it opened in 1883, John A. Roebling’s engineering wonder captivated artists and writers alike. Although unique to her, O’Keeffe’s works on the Brooklyn Bridge theme contain a nod to the Italian-born American Futurist Joseph Stella, who depicted the span in numerous studies and in five oils. His fractured compositions of the fabled structure reflect his modernist approach while simultaneously recalling the stained-glass windows of Gothic architecture: a marriage of the old with the new. In O’Keeffe’s monumental drawing, her formal inventions rival those of Stella. Like O’Keeffe, Walker Evans in several of his photographic series of the bridge (1928–30) put the viewer within its cables. Pioneering abstractionist O’Keeffe executed her Brooklyn Bridge trio around the time she left New York—after settling Stieglitz’s museum-quality estate—to live in New Mexico. As a group, they may have been a salute to her success in the City, a monument to the ability of bridges to connect people and places, or a gateway to her new life. O’Keeffe was known to have driven down to Wall Street on Sundays and back and forth across the Brooklyn Bridge. Unlike the arches in the painting, those of the drawing suggest the lobes of a heart, creating a valentine to New York, where she and Stieglitz had launched their careers COMMUNITY VOICE O’Keeffe was among my favorite artists, long before she came into our collection. The eroticism in her pictures, including in this one, is subtle and palpable at the same time. Sarah and I both loved the Brooklyn Bridge for many reasons. Now, inspired by the artist’s amazing vision, we see the Bridge in a new way as this piece emotes a uniquely different powerful feeling. Elie Hirschfeld New York City real estate developer

ClassificationsDRAWINGS

Collections

- Scenes of New York City: The Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld Collection

PHOTO OF THE DAY

ROCKEFELLER PLAZA

ALL IN FLORAL SPLENDOR

CREDITS

NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY BLOG

Collections

- Scenes of New York City: The Elie and Sarah Hirschfeld Collection

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment