Thursday, May 29, 2025 – THE DELICIOUS FRUIT AND ITS BEGINNINGS IN NEW YORK

CHERRIES IN AMERICA

& THE

RISE AND FALL OF

CHERRY STREET, MANHATTAN

JAP HARSKAMP

NEW YORK ALMANACK

THURSDAY, MAY 29, 2025

ISSUE #1459

Cherries in America & The Rise and Fall of Cherry Street, Manhattan

The Queens-bound F train platform of Delancey and Essex Street Station features three cherry tree murals as well as several smaller cherry mosaics. Created in 2004 by the Shanghai-born and New York City-based sculptor Ming Fay, “Delancey Orchard” glass mosaic is an allusion to the farm land that once belonged to a Loyalist family.

Étienne De Lancy was a French Huguenot refugee from Caen; his wife Anne descended from the prominent Dutch-American Van Cortlandt family. In the course of his career their eldest son James De Lancey (born in 1703) served as Chief Justice, Lieutenant Governor and acting Colonial Governor of the Province of New York.

Up until the Revolutionary War, the family owned a 300-acre farm which stretched from the East River to the Hudson (having sided with the British during the Revolutionary War, James’s assets were confiscated by the authorities).

Located on what is today Orchard Street, the pride of the Delancey farm was a cherry grove. When the property was divided up among smaller landowners who were eager to remove all reminders of a British past, the orchard was destroyed.

There are other memories of a cherry culture. In the midst of the Inwood neighborhood, surrounded by towering apartment block at the corner of Broadway and 204th Street, stands a two-story Dyckman Farmhouse Museum that was built in 1784 by William Dyckman. Family members too took pride in their orchards (a cherry tree in the backyard may be a survivor from the original fruit garden). The dark “Dyckman Cherry” was a sought after species in its day.

Today, there are plenty of reminders of Manhattan’s passion for cherries (including a classic cocktail). The history of the fruit’s introduction and cultivation runs parallel to the city’s foundation and expansion.

Cherry Cultivation

Sweet cherries originated in the fertile lands of the region between the Black and Caspian Seas and were most likely brought to Europe by birds. Mentioned by Theophrastus in his History of Plants (3rd century BC), the author claims that the Greeks had been the first to grow cherries.

The Romans continued the tradition by cultivating the fruit on a larger scale. Their conquering armies brought trees with them to newly occupied territories; by the first century AD cherries were grown throughout Europe.

Early production was limited to personal consumption or local trade. One of the first known commercial cherry orchards was established in the Rhine Valley in the fourteenth century. By the sixteenth century farmers in the Low Countries were praised for their agricultural expertise.

As early as 1556 physician Gheraert Vorselman published Eenen nyeuwen coock boeck (A New Cook Book), the earliest Dutch compilation to include recipes for salads and vegetable dishes. Fruit was widely available, but cherries remained a symbol of wealth and privilege. It was not until the Renaissance that they became more widely available.

Throughout the seventeenth century the Dutch and Flemish enjoyed the reputation of being the best-fed populations in Europe. Domestically they produced a rich diet of bread, butter, cheese, fruit and vegetables. Techniques of preserving food were also well advanced. Settlers from the Low Countries in Manhattan brought with them the experience of growing fruit and veg as well as a passion for gardening.

The first colonials in the region were transient traders, not home makers. Actual settlement did not begin until Peter Minuit acquired Manhattan Island, but frequent hostile confrontations prevented land management until Peter Stuyvesant took over as Governor in 1647. According to records of that year, the latter planted an apple tree brought over from the Netherlands on the corner of what is now Third Avenue and 13th Street.

Stuyvesant was a farmer and a soldier. In 1651 he purchased the land from the West India Company (WIC) that would become known as the Stuyvesant Farm or Great Bowery. He did not live there until the English took possession of New Amsterdam in 1664. Having retired from politics, Peter devoted his energy to agriculture.

Using slave labor, his orchards and gardens were well kept according to contemporary accounts. Part of the original purchase, mainly along the Bowery and Fourth Avenue, remained in the hands of Governor’s descendants until the death of Peter Winthrop Rutherfurd Stuyvesant in 1970.

Cherries in New Amsterdam

In 1622, a resident of Amsterdam named Nicolaes Van Wassenaer began to publish (at intervals) a Historisch verhael (historical account) of events in New Netherland. His reports were based on facts supplied by officials of the WIC, communications from settlers in the colony, and rumors that were spread by sailors and former Company employees.

In December 1624, Van Wassenaer reported on the abundance of edibles in the colony, including plants and wild fruit. He made one specific exception: “Cherries are not found there.”

Sweet cherry cultivation in North America began at some time after the arrival of Europeans. Early settlers brought cherry pits with them to plant in their gardens. Cherry trees appeared in the settlements of Virginia and Massachusetts and they were a feature in the gardens of French newcomers in their Midwestern outposts.

The Dutch introduced cherries to New Netherland. One of the earliest instances of their cultivation was recorded in the Hudson Valley during the late 1600s.

There are two versions on the origin of the names Cherry Hill and Cherry Street (established in colonial times to run from the intersection of Pearl Street and Frankfort Street in Lower Manhattan).

Born in Amsterdam in August 1611 into a family of Huguenot descent (the French name was Prévost), David Provoost made his first journey to New Netherland in 1624 as a thirteen year old, two years before the island of Manhattan was purchased from Native Americans. He returned in April 1639, a married man working in various diplomatic functions for Governor Willem Kieft and the WIC.

Provoost was the original grantee of a considerable parcel of land in New Amsterdam. Having cleared the land, he built a farm house near the East River shore at a point which is believed to be in the interior of the block between the modern Pearl and Water Streets, Dover Street and Peck Slip.

There he created a small orchard that was long remembered as the “Cherry Garden.” Although Provoost later moved to Long Island (he died in Breukelen = Brooklyn; his grandson was the 24th Mayor of New York; his great grandson became the city’s first Bishop), his orchard was commemorated when the area was given the name Cherry Hill.

Other historians argue that Cherry Street was named for the seven-acre orchard that was owned by Goovert Loockermans, a wealthy merchant who was a representative of the Amsterdam trading firm Gillis Verbrugge & Company in the 1660s.

Loockermans was said to produce the best cherries in town. The orchard was lost in 1672 when his heirs sold the land for sixty dollars to the brewer Richard Sackett who turned the land into a beer garden and bowling-green known locally as Sackett’s Orchard.

Cherry Street Elite

By the second half of the eighteenth century Cherry Hill was becoming a fashionable area that attracted both moneyed families and entrepreneurs.

In 1786, Founding Father and merchant John Hancock had moved into the property at 10 Cherry Street; New York City’s first Governor DeWitt Clinton resided nearby on Pearl Street. In April 1818 clothing retailers Brooks Brothers opened their first shop there.

The residence at 7 Cherry Street, the home of Samuel Leggett (1782-1847, President of the New York Gas Company), was the first house illuminated with gas lamps in 1825. Close by stood fashionable Franklin Square, a chosen hub of the city’s elite lawyers and financiers.

The trend to settle in the area had been set by Walter Franklin, a Quaker merchant and importer of goods from China and the South Seas who had been actively involved in the American Revolution, first as a member of the Committee of One Hundred (opposing the laws of the British Parliament) and then as a representative of the first New York Provincial Congress (formed in 1775).

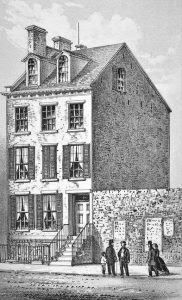

Having amassed a fortune, Franklin retired from business and built an elegant Georgian style mansion at the northeast corner of Pearl and Cherry Streets. Erected in 1770, it was considered to be one of the finest homes in the city. He subsequently married a young Quaker “milkmaid” by the name of Maria Bowne. The couple had two daughters.

Walter died in June 1780. When some six years later Maria remarried Samuel Osgood, a Massachusetts politician and lawyer who had recently settled in the city of New

York, the family continued living in the Cherry Street Mansion (the pair needed the space as they would have six more children).

Osgood had fought his way through the Revolution, having participated in the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. He also saw action during the Siege of Boston. By the end of the war he had attained the rank of Colonel. In 1785 he moved to New York to take on the position of Commissioner of the Treasury. Walter Franklin’s mansion became known as Osgood House.

Presidential Palace

On April 14, 1789, the Electoral College informed George Washington at Mount Vernon that he had been unanimously elected First President of the United States. Nine days later he arrived in New York, then the nation’s capital, for his inauguration. It was Washington’s first trip to the city since the end of the Revolutionary War and he was given a hero’s welcome as both a victorious General and newly-elected President.

For the triumphal voyage a special barge had been constructed with thirteen oars on both sides (dressed in white, all oarsmen under command of coxswain Thomas Randall were New York pilots). Thousands of people packed the waterfront between the Battery and Wall Street to greet the barge on arrival. Governor George Clinton met the President as he landed at Murray’s Wharf.

In preparation for his arrival in Manhattan, Congress had made considerable effort to find a suitable property that would serve as “Presidential Palace” (the term remained in circulation until the White House was built).

They finally agreed on the lease of Osgood House. Housing the President, his family and household staff, 1 Cherry Street became the first seat of the federal government’s executive branch.

It was from here that in October 1789 the President penned his first Thanksgiving proclamation, setting aside – as a cherry on the cake – a Thursday each November as a national holiday.

It soon became clear that the Cherry Street mansion was too small to function both as a Presidential residence and a workplace. When Comte de Moustier, French Minister to the United States, vacated the large four-story Alexander Macomb mansion at 39/41 Broadway on his return to France, the property was made available to the Washington family and staff. They moved into their new residence in February 1790.

Osgood House was demolished in 1856. In spite of its historical pedigree, the district had by then changed dramatically and devolved into a neighborhood of overcrowded tenements, paralleling the decline of nearby Five Points. Quaker John Franklin had initiated the rise of Cherry Street. The name of another Friend is associated with its demise.

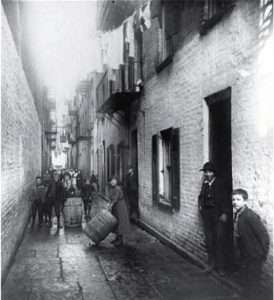

In 1850/1 a “model tenement” named Gotham Court was opened at 38 Cherry Street. It comprised two rows of six tenement blocks, each five stories high, standing back to back. The complex was built by the Quaker philanthropist Silas Wood for the purpose of improving the life of local residents and immigrants who occupied dreadful “rookeries” in the district. It did not stop the area’s rapid decline.

In 1862, a sanitary official reported rampant infectious disease and high child mortality in the properties. Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives (1890) described Gotham Court as one of the “worst tenements along the East River.”

For Riis, the block stood as a symbol of Manhattan’s squalid living conditions. The court was demolished seven years after publication of his book; the rest of the area would follow. Cherry Hill was erased from the map. In its place would rise the Alfred E. Smith Houses.

ON ASCENTION

REMEMBERING THOSE BURIED ON HART ISLAND

ON THIS HOLIDAY, MAY 29TH, A GROUP OF FRIENDS AND FAMILY REMEMBER THOSE BURIED ON HART ISLAND AT THE MUNICIPAL CEMETERY. THIS YEAR THE WEATHER DID NOT PERMIT THE SERVICE TO BE HELD ON THE ISLAND. IT WAS HELD AT GRACE EPISCOPAL CHURCH ON CITY ISLAND.

Hart Island in the mist, just 5 minutes from City Island

Grace Episcopal Church is a lovely landmark on City Island

The Chapel’s stained glass window celebrates those who went to sea in this waterfront community.

WANTED

FOR OUR 50TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION

“KEEPING HISTORY ALIVE”

PHOTOS OF THE ISLAND, THE PEOPLE, PLACES, EVENTS THAT MADE OUR COMMUNITY FROM 1975 TO TODAY.

SEND US YOUR PHOTOGRAPHS OF LIFE ON THE ISLAND FOR OUR EXHIBIT DURING OUR CELEBRATION STARTING JUNE 7.

CONTACT JBIRD134@AOL.COM FOR DETAILS.

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JUDITH BERDY

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2025 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment