Wednesday, March 10, 2021 – Far from the glamourous travel of the 20th century

The Roosevelt Island Historical Society and the New York Public Library are proud to host author Richard Panchyk and his presentation of his book “Abandoned Queens”.

TUESDAY, MARCH 16TH, 7 P.M. VIA ZOOM Click below to register:

https://www.nypl.org/events/programs/2021/03/16/abandoned-queens

There are many places in New York City’s borough of Queens where traces of the past linger, haunting reminders of the way things used to be, sometimes hidden and sometimes in plain sight. In this presentation, author Richard Panchyk takes us on a journey through his book Abandoned Queens, through a variety of fascinating abandoned places in Queens, including the chilling Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, the meandering remains of the country’s first modern highway, and a defunct airport reclaimed by wilderness. Because Queens is so densely populated, these abandoned places usually coexist adjacent to living, thriving locations, making for an often eerie and beautiful juxtaposition of old and new, used and unused. From an eerie old railroad line in Forest Hills to a destroyed neighborhood in the Rockaways, the poignant images in this book are filled with context and history.

WEDNESDAY, MARCH 10, 2021

THE 307th EDITION

FROM OUR ARCHIVES

CROSSING THE ATLANTIC

STEPHEN BLANK

Black Ball ship Montezuma By Antonio Jacobsen – Christie’s, LotFinder: entry 5648386 (sale 2670, lot 2030, New York, 25 January 2013), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23751297

Crossing the Atlantic, Part I

In March 1959, I left Dartmouth (long story), purchased the cheapest fare possible and boarded the Queen Mary (the original) from the famous Pier 54 and set off for Southampton. A total innocent, I had no idea of the ship’s grand salons and ballrooms I would never see. But I vividly remember climbing to the highest point I could reach and watching the stormy waves rise up to what seemed eye level before crashing down, more like broken glass than water. Over the next few years, I did two more Atlantic crossings and a mid-winter round trip sailing between Marseilles and Haifa. Only years later was I willing even to get on a river cruise.

But crossing the Atlantic by liner is a good story and very much involves New York. On board all.

Folks did sail across the Atlantic in colonial times. But few made the journey for pleasure. Businessmen, diplomats, men on the run – but most of the human cargo was migrants (coming and, about a third, returning).

Mail ships were the earliest regularly scheduled Atlantic crossings. The British Government started operating monthly mail brigs from Falmouth, Cornwall, to New York in 1756. These ships carried few non-governmental passengers and no cargo. Ben Franklin an amazing traveler, made eight crossings, possibly on these vessels.

In the early 19th century, sailing ships took about six weeks to cross the Atlantic. (Columbus made it in 36 days, but not all the way to New York.) With adverse winds or bad weather the journey could take as long as fourteen weeks. When this happened passengers would often run short of provisions which they had to bring on board themselves.

Early on, captains waited until they had a full enough ship and then departed. The novel idea was packet ships that departed from port on a regular schedule. The typical packet sailed between American and British ports, and the ships were designed for the North Atlantic, where storms and rough seas were common.

The first of the packet lines was the Black Ball Line, which began sailing between New York City and Liverpool in 1818. Packets were contracted by governments to carry mail and also carried passengers and timely items such as newspapers. The line originally had four ships, and it advertised that one of its ships would leave New York on the first of each month irrespective of cargo or passengers. Within a few years several other companies followed the example of the Black Ball Line, and the North Atlantic was being crossed by ships that regularly battled the elements while trying to remain on schedule.

Average time for packets to cross between New York and Liverpool was 23 days eastward and 40 days westward. But many times, crossing were much longer, and westward passages of 65 to 90 days were not uncommon. The best time from New York to Liverpool was the 15 days 16 hours achieved at the end of 1823 by the ship New York. American packets, based in New York, dominated this market.

Travel times might be better, but the trip was not very pleasant. Wealthier, more distinguished passengers fared a bit better. But it was rough sailing. One historian observes, “In 1842 the British government attempted to bring an end to the exploitation of passengers by passing legislation that made it the responsibility of the shipping company to provide adequate food and water on the journey. However, the specified seven pounds a week of provisions was not very generous. Food provided by the shipping companies included bread, biscuits and potatoes. This was usually of poor quality. One government official who inspected provisions in Liverpool in 1850 commented that ‘the bread is mostly condemned bread ground over with a little fresh flour, sugar and saleratus and rebaked’.” (SB: “fresh flour, sugar and baking powder and then baked again”)

Steam changed everything. Only a dozen years after Fulton’s Clermont steamed from New York City to Albany—150 miles—in 32 hours, the Savannah in 1819, an American sailing ship with auxiliary steam engines and two paddle wheels that could be folded away on deck, made the first steam-assisted crossing of the Atlantic. In reality, she (always “she”) used her engines only a fraction of the time and mostly when she was in sight of critical eyes ashore. No one could be found who was willing to risk the trip, so Savannah carried no passengers. In the end, the steam experiment failed, and Savannah was converted back to full sails. (The name Savannah appeared again in another unsuccessful experiment – the USS Savannah was the first and last nuclear powered merchant ship, in 1955.)

In 1838, the British and American Steam Navigation Co.’s Sirius left Ireland with 40 paying passengers for a historic voyage to New York. It took 18 days and the Sirius ran out of coal—the crew had to burn cabin furniture and even a mast—but it was the first passenger ship to cross the Atlantic entirely on steam power. There’s a story here, involving competition between lines and the beginning of a new era of Atlantic liner history.

The Great Western Steamship Company was an outgrowth of the yet incomplete Great Western Railway. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was chief engineer. The Great Western Company was ready to send its new ship, Great Western from Bristol to New York. The British and American Steam Navigation Company was also planning a transatlantic steamship service, but because its first ship was unfinished, British and American chartered the Irish Sea steamer, the Sirius from the St. George Steam Packet Company for two voyages. Sirius left Cork four days before Great Western departed, but Great Western still came within a day of overtaking Sirius to New York.

Because British and American did not begin its regular service until the following year, the Great Western Steam Ship Company is considered the first regular transatlantic steamship service. Great Western was launched in July 1837 and ready for her maiden Bristol-New York voyage the following April and the Company operated the first regular transatlantic steamer service from 1838 until 1846.

In fact, the Great Western Company didn’t achieve a dominant position in Atlantic passenger trade when it failed to win a mail contract – although it was a pioneer in ship building. Cunard was the winner.

With the birth of the Cunard Line in 1840 a steamship company promised to deliver its passengers to their destinations on a regular timetable. Cunard’s first four small steamers, all commissioned in 1840-41, had actually launched something completely new in ocean travel: constant, reliable service on a fixed schedule.

But wind was still important. These early steamers weren’t pure steamships, but wooden-hulled sailing ships with steam engines and great side paddle wheels. They used their sails whenever possible, to enhance speed and to promote fuel economy. Coal was bulky and expensive, and making steam was a noisy and dirty process. Nautical technology would need years of development before steam completely displaced sail.

The nineteenth century saw great waves of emigration from the Old World to the New, but in the early days of steam, few emigrants arrived under steam power. The four original Cunard ships, each with space for only 115 passengers, made no provision for steerage passengers at all, concentrating on their main task, which was the speedy and safe delivery of the Royal Mail.

The new world of the grand trans-Atlantic passenger steamship (whose revenues were largely based on immigrants in steerage class) was about to begin. It would include both the worst – Irish “coffin ships” – and the best – an entire new class of elegance in Atlantic travel. New York was the destination for most of these passages, but foreign companies dominated the industry.

Happy Sailing. Part II will depart soon.

Savannah https://almostchosenpeople.wordpress.com/2016/05/22/may-22-1819-ss-savannah-begins-first-trans-atlantic-trip-by-a-steam-ship/

Britannia of 1840, the first Cunard liner built for the transatlantic By Wikid77 -http://cunardline.tripod.com/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderpictures/rmsbritannia.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4242795

MARK YOUR CALENDARS FOR OUR EVENTS

UPCOMING PROGRAMS ON ZOOM

Registration will be available before each event

All events are at 7 p.m.

Tuesday, March 16 “Abandoned Queens”

Author Richard Panchyk takes us on a journey through Queens’ past. Revealing haunting reminders of the way things used to be, he describes fascinating, abandoned places, including the chilling Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, the meandering remains of the country’s first modern highway, a defunct airport reclaimed by wilderness, an eerie old railroad line in Forest Hills, and a destroyed neighborhood in the Rockaways.

Tuesday, April 20 “Mansions and Munificence: the Gilded Age on Fifth Avenue”

Guide, lecturer, author and teacher of art and architecture, Emma Guest-Consales leads a virtual tour of the great mansions of Fifth Avenue. Starting with the ex-home of Henry Clay Frick that now houses the Frick Collection, all the way up to the former home of Andrew Carnegie, now the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, she takes us through some of the most extravagant urban palaces the city has ever seen.

Tuesday, May 18 “Saving America’s Cities” Author and Harvard History Professor Lizabeth Cohen

Provides an eye-opening look at her award-winning book’s subtitle: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age. Tracing Logue’s career from the development of Roosevelt Island in the ‘70s, to the redevelopment of New Haven in the ‘50s, Boston in the’60s and the South Bronx from 1978–85, she focuses on Logue’s vision to revitalize post-war cities, the rise of the Urban Development Corporation.

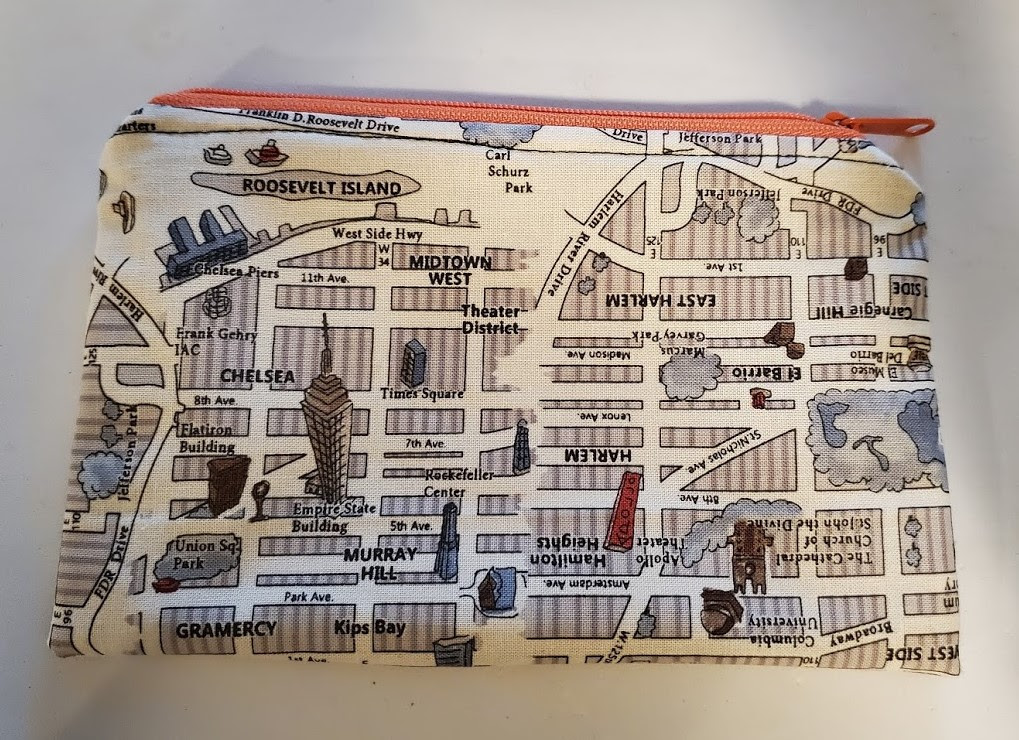

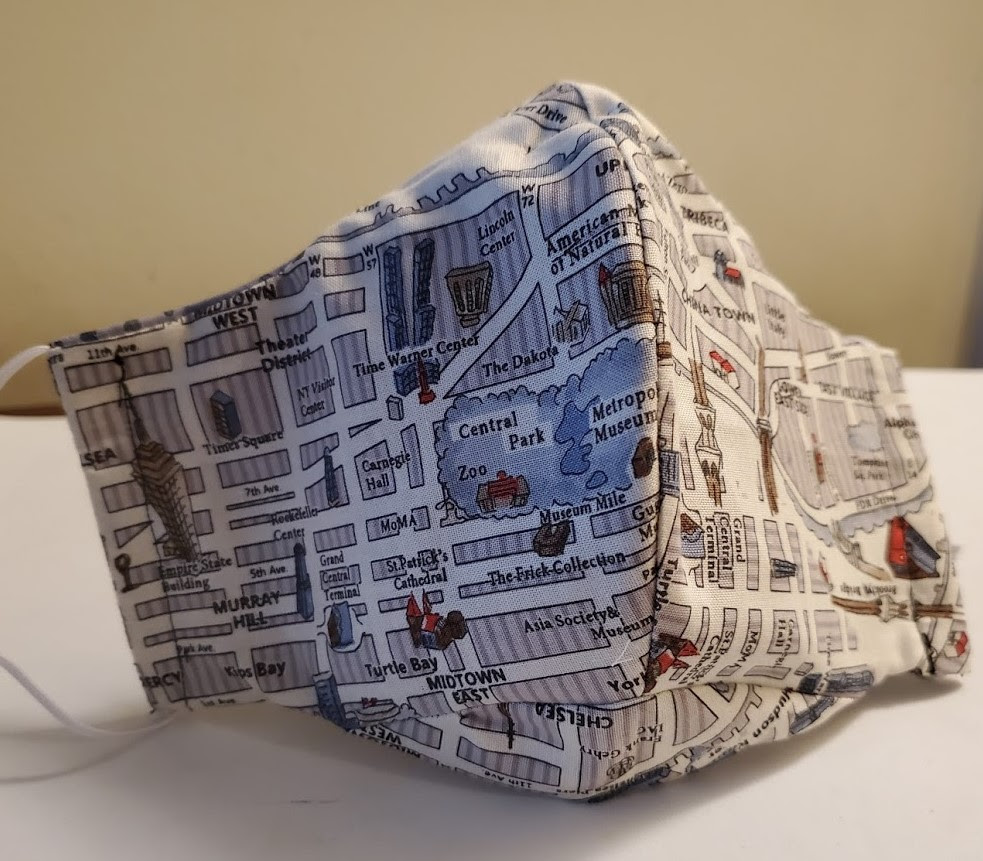

EXCLUSIVE NYC MAP DESIGN MASKS AND ZIPPER POUCHES

MASKS $18-, ZIPPER POUCHES $12-

AT RIHS VISITOR KIOSK

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

Can you identify this photo from today’s edition?

Send you submission to

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

ALBERTA HUNTER

Thom Heyer was the only person to recognize Miss Hunter.

** Yesterday’s image was the library at the Morgan Library.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

STEPHEN BLANK

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment