Tuesday, May 18, 2021 – IMAGINE A PRODUCT……..IT WAS PROBABLY MADE HERE FROM FURS TO GLOVES AND MORE

TUESDAY, MAY 18, 2021

The

366th Edition

From the Archives

The John Vogt & Co.

Store

502-504

BROADWAY

The John Vogt & Co. Store – 502-504 Broadway

The private homes of Manhattan’s wealthy citizens had moved northward before 1853 when the luxurious marble-fronted St. Nicholas Hotel opened on Broadway between Spring and Broome Streets. The exclusive hotel, which cost about $1 million to construct, would attract handsome retail stores around it.

In 1859 Homer Bostwick hired architect John Kellum to design an upscale emporium building across the street from the St. Nicholas, at Nos. 502-504 Broadway. Kellum had just dissolved his partnership with Gamaliel King, and was now partnered with his son as Kellum & Son.

The private homes of Manhattan’s wealthy citizens had moved northward before 1853 when the luxurious marble-fronted St. Nicholas Hotel opened on Broadway between Spring and Broome Streets. The exclusive hotel, which cost about $1 million to construct, would attract handsome retail stores around it.

In 1859 Homer Bostwick hired architect John Kellum to design an upscale emporium building across the street from the St. Nicholas, at Nos. 502-504 Broadway. Kellum had just dissolved his partnership with Gamaliel King, and was now partnered with his son as Kellum & Son.

The cast iron storefront of clustered columns and regimented arches was manufactured by the Architectural Iron Works. Its catalogue listed these capitals as “Gothic.” Above, the four stories of white marble were distinguished by two-story arches, separated by slim engaged columns which would later earn the style “sperm candle” because of the similarity to candles made from the waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale.

Kellum & Son stacked nubby, faceted blocks up the side piers, which provided a somewhat incongruous frame when compared with the otherwise gentle lines of the facade. Below the stone cornice a corbel table carried on the arched motif. High above Broadway two stone urns were the finishing touches.

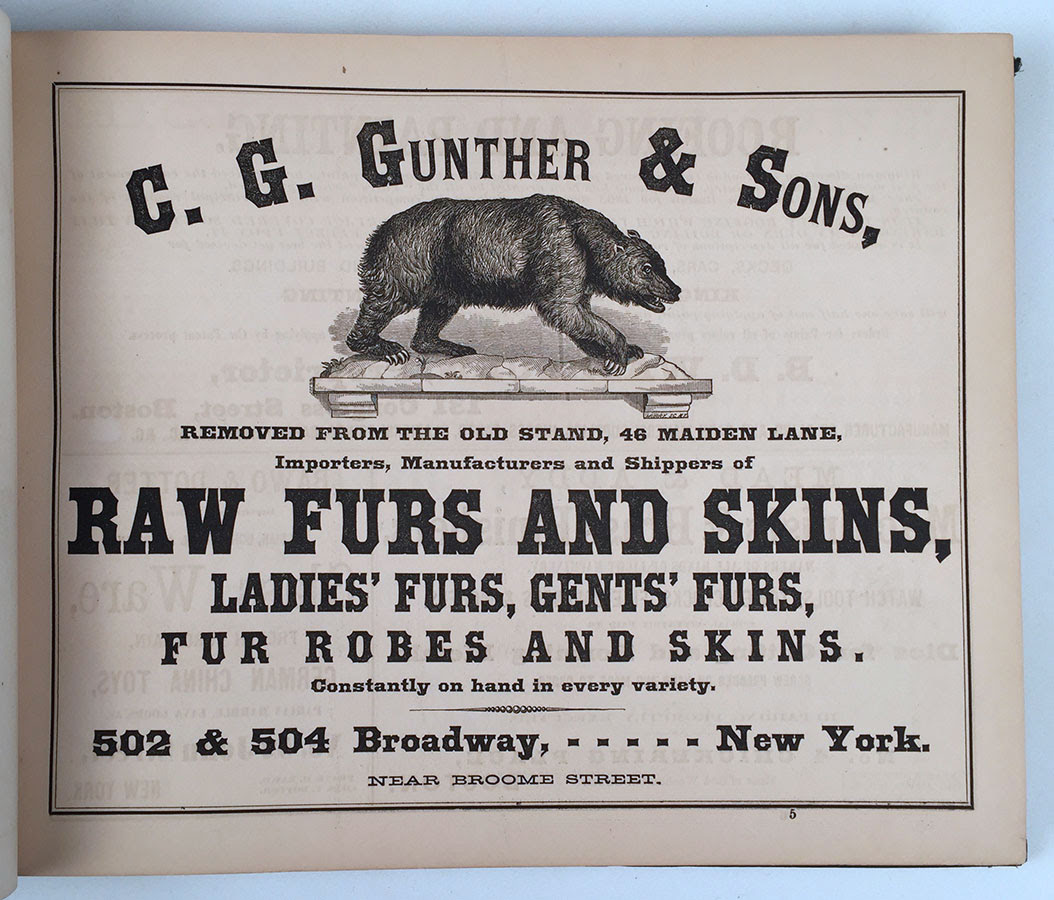

While the building was completed in 1860, the Civil War prevented tenants from moving in until 1866. That year C. G. Gunther & Sons moved into the top floor. Described as “The oldest and largest fur house in the United States,” it was founded in 1820 by Christian G. Gunther at No. 46 Maiden Lane and remained at that location until now. The firm, now headed by C. Godfrey Gunther, not only imported raw furs and skins, but manufactured fur clothing and accessories.

In May 1866 china and “fancy goods” dealers John Vogt & Co. moved into the first four floors. Founded in 1852 it had been operating from William Street. In its new store, according to the History of New York in 1868, “may now be seen the most magnificent and choice stocks of merchandise” and “an endless variety of curious, chase, quaint, and elaborate designs, and combining superb beauty of shapes, colors, and embellishments with rare excellence of materials and most exquisite workmanship in respect to moulding, carving, etc.”

The first floor was the “Porcelain Ware” showroom. Here well-do-to female shoppers browsed among dinnerware, tea services, and “toilet ware.” The second floor contained “Bohemian and Belgian Glass Ware, Lava Wave, German China, and Parian Marble.” Reproductions of classical statuary suitable for Victorian parlors were available here. Among the copies available in 1868 were “Cupid captive by Venus; Sybilla, with guitar; Paul and Virginia (from that memorable and pathetic story); [and] Mounted Amazon attacked by a leopard.” The third and fourth floors were used for warehousing stock.

Only four months after John Vogt & Co. opened, disaster struck. On October 8, 1866 The New York Times reported “A destructive fire occurred in the marble building No. 502 Broadway, on Saturday night. The building was occupied by C. G. Gunther & Sons, furriers, and John Vogt & Co., dealers in china and glass.” The devastating fire roared through the floors and sparks set St. Patrick’s Cathedral several blocks away on Mott Street ablaze.

Damage to the church and “its interior adornments” were estimated at $150,000; while the Broadway emporium was gutted. The Times reported “the edifice was reduced to ashes.” The losses suffered by John Vogt & Co. and C. G. Gunther & Sons was around $350,000–approximately $5.4 million in 2017.

The History of New York noted “the whole edifice underwent a thorough and costly refitting and adornment.” Undaunted, both companies moved back into the restored building.

By 1872 John Vogt & Co. had left and C. G. Gunther’s Sons had expanded throughout the lower floors. Formerly a wholesale house, it now opened both a men’s and a women’s store. On December 28, 1872 an advertisement in Harper’s Bazaar offered “Ladies’ Furs,” an “elegant assortment of seal-skin fur, in all the leading styles of sacques and turbans.”

Choosing its audience carefully, C. G. Gunther’s Sons placed its ad for menswear that same month in the Army, Navy, Air Force Journal & Register. The advertisement gave a hint of the wide variety of items manufactured and sold here. Well-to-do patrons were offered “caps, collars, gloves, gauntlets, etc., including the latest styles in seal skin fur.” There was also a “large and elegant stock of fur robes and skins for carriage and sleigh use” and “seal coats and vests.”

Earlier that year, in October, the New-York Tribune dedicated an article to C. G. Gunther’s Sons. It described the luxurious pelts used to create items worn by Manhattan’s wealthiest citizens. “The most costly furs are those made from the Russian and ‘Crown’ Sable, which always have been and always will be fashionable.” The article explained that the term “Crown” sable indicated these were the skins used by the Czar.

The prices quoted were an indication of the C. G. Gunther’s Sons’ carriage trade customers. “The price of a set, consisting of muff and boa, or collar, varies from $115 to $1,000. The darker the fur the more expensive, other things being equal.” The cheapest price mentioned would be equal to about $2,300 today; the most expensive about $20,000.

The Tribune’s article included mention of the extraordinary number of furs–a list that would shock readers today. Included were fox, chinchilla, mink, ermine, seal, beaver, monkey, marten, bear, buffalo, wolverine, lynx and wildcat. The writer decided “the purchasers who cannot find their wants immediately supplied must be difficult to please.”

A would-be burglar was attracted to the expensive goods within the store early on a September morning in 1874. Michael Moreno, described by The Times as “an Italian living at No. 59 Crosby street,” was noticed loitering outside by the night watchman. The guard used a forceful incentive to prompt the Moreno to move on; but was trumped. “The watchman caught hold of the Italian and drew his club, as if to strike him, when the latter drew a revolver.”

Hearing the commotion, Police Officer Corey rushed in. He grabbed Moreno by the collar, only to find the revolver now pointed at him. For his bold move Moreno received a “stunning blow on the forehead” by the policeman’s baton.

The blow was severe enough that the next morning he was moved from his jail cell to Bellevue Hospital. But he had not learned his lesson about 19th century law enforcement yet. The newspaper reported that he was “so threatening” that an officer was called in to help the nurses undress him. Finally he was placed in a strait-jacket.

If the authorities had searched Moreno for weapons, they missed his knife. He managed to escape from the strait-jacket then attacked the police officer with the knife. The policeman “was obliged to use his club to protect himself.” It all ended badly for the combative would-be burglar. “At a late hour last night Moreno was lying in a dangerous condition in the hospital,” reported The Times on September 19, 1874.

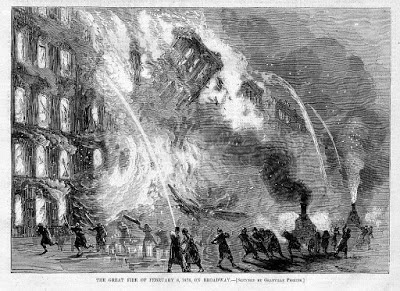

Although C. G. Gunther’s Sons had returned to the building after the ruinous fire a decade earlier, it would no do so in 1876. The conflagration of February 8 quickly became known nation-wide as the “Great Broadway Fire.” The Tribune described it in florid Victorian prose saying “The air rushed into the vortex of the ascending flame from every direction, and lifted the fire in gigantic billows that rolled aloft in roaming surges to a great height.”

Structures along Broadway collapsed during the massive fire. Harper’s Weekly, February 1876 (copyright expired)

Choosing its audience carefully, C. G. Gunther’s Sons placed its ad for menswear that same month in the Army, Navy, Air Force Journal & Register. The advertisement gave a hint of the wide variety of items manufactured and sold here. Well-to-do patrons were offered “caps, collars, gloves, gauntlets, etc., including the latest styles in seal skin fur.” There was also a “large and elegant stock of fur robes and skins for carriage and sleigh use” and “seal coats and vests.”

Earlier that year, in October, the New-York Tribune dedicated an article to C. G. Gunther’s Sons. It described the luxurious pelts used to create items worn by Manhattan’s wealthiest citizens. “The most costly furs are those made from the Russian and ‘Crown’ Sable, which always have been and always will be fashionable.” The article explained that the term “Crown” sable indicated these were the skins used by the Czar.

The prices quoted were an indication of the C. G. Gunther’s Sons’ carriage trade customers. “The price of a set, consisting of muff and boa, or collar, varies from $115 to $1,000. The darker the fur the more expensive, other things being equal.” The cheapest price mentioned would be equal to about $2,300 today; the most expensive about $20,000.

The Tribune’s article included mention of the extraordinary number of furs–a list that would shock readers today. Included were fox, chinchilla, mink, ermine, seal, beaver, monkey, marten, bear, buffalo, wolverine, lynx and wildcat. The writer decided “the purchasers who cannot find their wants immediately supplied must be difficult to please.”

A would-be burglar was attracted to the expensive goods within the store early on a September morning in 1874. Michael Moreno, described by The Times as “an Italian living at No. 59 Crosby street,” was noticed loitering outside by the night watchman. The guard used a forceful incentive to prompt the Moreno to move on; but was trumped. “The watchman caught hold of the Italian and drew his club, as if to strike him, when the latter drew a revolver.”

Hearing the commotion, Police Officer Corey rushed in. He grabbed Moreno by the collar, only to find the revolver now pointed at him. For his bold move Moreno received a “stunning blow on the forehead” by the policeman’s baton.

The blow was severe enough that the next morning he was moved from his jail cell to Bellevue Hospital. But he had not learned his lesson about 19th century law enforcement yet. The newspaper reported that he was “so threatening” that an officer was called in to help the nurses undress him. Finally he was placed in a strait-jacket.

If the authorities had searched Moreno for weapons, they missed his knife. He managed to escape from the strait-jacket then attacked the police officer with the knife. The policeman “was obliged to use his club to protect himself.” It all ended badly for the combative would-be burglar. “At a late hour last night Moreno was lying in a dangerous condition in the hospital,” reported The Times on September 19, 1874.

Although C. G. Gunther’s Sons had returned to the building after the ruinous fire a decade earlier, it would no do so in 1876. The conflagration of February 8 quickly became known nation-wide as the “Great Broadway Fire.” The Tribune described it in florid Victorian prose saying “The air rushed into the vortex of the ascending flame from every direction, and lifted the fire in gigantic billows that rolled aloft in roaming surges to a great height.”

Buildings collapsed, others were gutted. Nos. 502-504 Broadway was heavily damaged. The tailor’s trimmings firm of Lesher, Whitman & Co. took advantage of catastrophe by quickly purchasing the building. Three days later, even while The Times remarked “The public interest in the ruins of the buildings destroyed by fire Last Tuesday night was unabated yesterday,” it reported “Messrs. Lesher, Whitman & Co. yesterday purchased the premises No. 502 and 504 Broadway, at present occupied by Messrs. C. G. Gunther & Co. as a fur store.”

The article explained that Lesher, Whitman & Co. would take over the building “as soon as Messrs. Gunther & Co. shall have removed.” One month later C. G. Gunther’s Sons moved into “the new and capacious building No. 184 Fifth avenue” at 23rd Street.

According to a 1943 New York Times article, 104 patients were evacuated in accordance with an order by Mayor LaGuardia to close childcare institutions in order to conserve oil during World War II. LaGuardia noted that if Neponsit Hospital closed, 300,000 gallons of oil would be saved, which would lead to a 10% reduction of New York City’s fuel oil. Two years later in 1945, the hospital reopened, but mainly to veterans. The US Public Health Service leased the hospital to treat veterans with tuberculosis for five years.

In 1952, the Queens Hospital Center was created through the merging of Queens General Hospital and Triboro Hospitals, and Neponsit Beach Hospital was absorbed into this new medical center. Yet despite talks of expanding Neponsit into a general hospital, Neponsit closed in 1955, as tuberculosis cases declined significantly in the 1950s.

For the next few years, many New York agencies struggled to discover the best use for the building. New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses proposed expanding Jacob Riis Park onto the hospital land, replacing hospital buildings with sports fields and a swimming pool. The New York City Planning Commission actually approved this expansion unanimously, but the Board of Estimate overturned the plan. In the meantime, others proposed converting the hospital into housing, while others proposed turning the building into a nursing home. By 1959, construction began on the main building and the nurses’ residence, and in 1961 the Neponsit Home for the Aged was opened.

Lesher, Whitman & Co. conducted business from the restored building with little fanfare for more than a decade. The only upheaval seems to have been the ongoing battle with the New York District Rail Company in 1886 and 1887. The company proposed to build a “railroad underneath Broadway.” Stephen R. Lesher, head of the firm, vehemently fought against it.

It was not until 1889 that trouble came; not through business troubles, but through love. Stephen Lesher’s son, Charles S. Lesher, was 20 years old at the time and still lived in the family’s handsome house at No. 330 Madison Avenue. He was employed by the insurance firm Weed & Kennedy on Pine Street.

The young man became enamored with 28-year old Leonore Mitchell, described by The Times as “a handsome woman.” Shockingly, Lenore asserted that the two were “on intimate terms,” and Charles admitted, according to the newspaper, “that he had spent a good deal of his time in her company.”

But, according to Leonore, he became fiercely jealous. It came to a climax when he called on her at her home at No. 21 West 31st Street on March 4. During the preliminary hearing she declared he “induced her to drink a glass of wine in which he poured a quantity of digitalis.” Soon afterwards she became ill and “was compelled to call in a doctor, who saved her life.”

Lesher was arrested for attempted murder. His accuser appeared in the courtroom on May 14 “fashionably attired and was accompanied by a colored maid, Laura Paul.” She told the court that when he called on her a few days after the incident, he admitted to poisoning her; “but said that he had been drinking, or he would not have done it.”

Lesher insisted it was all a lie and that Leonore was simply attempting to blackmail him. He claimed to have a letter from her in which she confessed to attempted suicide. His father provided the $1,000 bail pending his court case.

More heartbreak came to the Lesher family six years later when Charles’s older brother Stephen visited the family’s ranch at Rockwood Station, Texas. While riding there his horse stepped into a prairie dog burrow and fell, rolling on top of Lesher. He suffered internal injuries and decided to return to New York “to get competent advice.” Doctors gave him morphine to ease the pain on the trip.

There was no railroad connecting Texas and New York; so Lesher boarded the steamer Neuces. According to other passengers, when the 35-year old went to his berth at 11:00 on the night of June 18, he was “cheerful.” But when Stephen Lesher, Sr. met the Neuces in New York Harbor four days later he would not be greeting his son, but retrieving his body. The 35-year old had been found dead in his berth, the apparent victim of an overdose.

At the time Wertheimer & Co., makers of gloves, was also in the Broadway building. On Christmas Eve 1891 Bloomindale’s ran an advertisement noting “Special–We have secured the entire sample stock of Lined Gloves from Wertheimer & Co…Ladies’ and Men’s, with and without fur tops.” The department store announced that although they were normally priced at up to $2.98 per pair, “We shall put these out as a great Holiday Special at 79c. per pair.” The store warned “Only 1,200 pairs; lingerers may be losers.”

Lesher, Whitman & Co. would remain in the Broadway building until 1900. In the meantime, other firms leased space. Benjamin & Caspary, cloak makers, were here by 1897. The firm sent a letter to the Citizens’ Union headquarters in October that year, endorsing Seth Low for reelection to mayor. It said in part “We wish to inform you that we are enthusiastically in favor of the election of Seth Low.”

The endorsement may not have been totally unbiased. Seth Low owned the Broadway building at the time and was, therefore, Benjamin & Caspary’s landlord. The property values along Broadway were an undergoing astonishing boom. In 1898 502-504 Broadway was valued at $250,000 and a year later at $300,000.

As Lesher, Whitman & Co. moved out, D. Jones & Sons moved in. The wholesale shirt makers were best known for their “Princely” and “Emperor” brands. In January 1901 The American Hatter insisted “No shirt buyer can afford to miss this line. Everything that is desirable in plain, fancy and negligee, or any variety of shirt, is here.”

Meinhard-Cozzens offered a variety of elegant women’s collars. Fabrics, Fancy Goods and Notions, December 1905 (copyright expired)

Headed by Dramin Jones, the firm included sons Joseph, Morris and Henry. Calling itself “the largest producers of popular priced shirts in the world” in 1902, it maintained a massive factory in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

The company was joined in the building on January 1, 1904 by Meinhard-Cozzens Company, makers and sellers of ladies’ neckwear and belts. “Neckwear” for women in 1904 referred to the high, stiff collars indispensable to a fashionable Edwardian wardrobe.

By 1909 another women’s neckwear company had moved in. Klauber Bros. & Co. advertised “Embroideries, Laces, Neckwear, and Novelties.” In November 1911 when Seth Low sold the building to Charles Lane, the three tenants were still here. D. Jones & Son was now known as Phillips-Jones Co.; but was still selling its highly-successful Emperor Shirts. Lane paid Low $251,000 for the property, a price the astonished Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide pointed out was “$194,000 less than the assessed value.”

Lane quickly resold the building a month later. On December 23 the Record & Guide hinted “The buyer is said to be the Coca-Cola Co.” The rumor was colorful but false. The purchaser was William H. Browning of Browning, King & Co. clothiers. He told reporters he had not decided what he would do with the property and “that the purchase was merely for investment.”

Throughout the next nine years the building continued to house apparel manufacturers. Philips-Jones employed 150 men, and 23 women in their shirt making shop. In 1917 another shirt manufacturer, Goodman, Cohen & Co. took 12,500 square feet of space; while Everett, Heaney & Co. dealt in fabrics.

For the first time in decades Nos. 502-504 Broadway was home to just one company when S. Blechman & Sons leased the entire building in July 1920. Listed in directories as “dry goods distributors,” the firm produced hosiery, underwear and other knit goods. And it found itself at odds with the labor unions several times over the next few years.

In 1934 management won a court order prohibiting strikers from carrying picket signs in front of the building. When the union refused to comply, S. Blechman & Sons went back to court, asking for a contempt of court ruling. In a case of deja vu the firm was back in court in 1937 when the union “flouted the injunction which restrained it from carrying signs…asserting that S. Blechman Sons, Inc…was unfair to labor.” The union was fined $250 for that offense.

The following year Simon Blechman commissioned architect Harry Hurwit to design the company’s new $65,000 building. Then in what was apparently a sudden change of mind, it purchased the old Rouss Building at Nos. 549-555 Broadway.

| The building was home to Canal Jeans on a much-changed Broadway. photo by Edmund Vincent Gillon from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York |

The stretch of Broadway had not been the shopping district of the carriage trade for decades. Until the last quarter of the century its once-elegant buildings would be overlooked and abused. With the renaissance of the Soho neighborhood, Canal Jeans leased ground floor of 502-504 Broadway in 1992.

Through it all, little changed to Kellum & Son’s striking 1860 facade. In 2003 Bloomingdale’s leased the former Canal Jeans store in the building where 112 years earlier it had purchased an entire line of gloves.

WHY 502?

Who would be interested in this building? I am. My father’s business was located in 502 for some years in the 1960’s and 1970’s. In those days, a rowboat was in front of the building filled with jeans that were sale in Canal Jeans.

My father was always in the textile business. Lower Broadway was full of manufacturers, converters, wholesales, jobbers and related industries. These cast iron buildings have immerse floor strength and could support die presses and heavy industrial equipment.

502 was a vast building going thru to Crosby Street and was far from a glamorous address in those years.

My father’s textile businesses ranged from manufacturing brassieres in the early years and then inside linings for men’s neckties. Like all our self taught manufactures of the past he could take on a new product easily and continue the small manufacturer business that are vanishing in New York.

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR SUBMISSION TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

ANSWERS WILL BE PUBLISHED ON WEDNESDAY

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

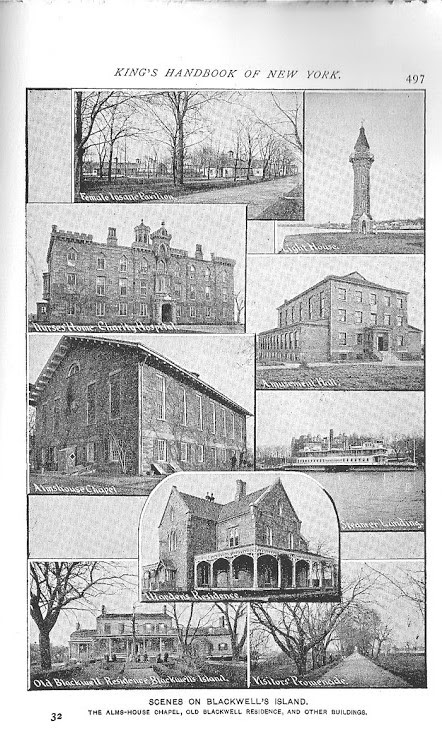

THE KING’S HANDBOOK OF NEW YORK CITY 1895

The Photos are

FEMALE INSANE PAVILLION, LIGHTHOUSE

SMALLPOX HOSPITAL, AMUSEMENT HALL

ALMSHOUSE CHAPEL, STEAMER LANDING

WARDEN’S RESIDENCE

BLACKWELL MANSION, VISITOR PROMENADE

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

Sources

DAYTONIAN IN MANHATTAN

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment