Monday, August 30, 2021 – Blasting a way to get from the east to west side of northern Manhattan

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, AUGUST 30, 2021

THE 454th EDITION

Manhattan

Becomes an Island!

Stephen Blank

When did Manhattan become a true island?

Not in ancient times. Not even long ago. Only in 1895!

With the opening of the Harlem River Ship Canal. The Harlem River Ship Canal was one of the major infrastructure works in our country’s history and reshaped Manhattan – now Manhattan Island.

Today, we can sail north from our Island, and bear west on the Harlem River, around Manhattan and into the Hudson. We pass the Spuyten Duyvil Bridge, a swing-open railroad bridge which connects Manhattan and the Bronx. It’s only used by Amtrak traffic now, but in years past, it handled freight, passenger and all manner of trains. On the Bronx side is the neighborhood of Spuyten Duyvil. Both the neighborhood and the bridge are named after Spuyten Duyvil Creek, a small estuary that connected the Hudson River to the northern tip of the Harlem River. The creek wandered north of what is known today as Marble Hill, which was then well-connected to Manhattan.

Shallow and rocky, the creek was barely navigable even for small boats. In 1817, a narrow canal, called the ‘Dyckman Canal’, was dug to permit small craft traffic to sail south of Marble Hill. It allowed rowboats and small private sailing vessels to move between the upper part of Manhattan and the wider, western end of the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, connecting the Hudson and Harlem Rivers. Steam vessels, however, were far too large to make the passage.

With the opening of the Erie Canal in 1821, shipping traffic on the Hudson increased greatly. Some of these ships were bound for Long Island Sound (and vice versa). If only they could fit through the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, valuable time and money wouldn’t be lost sending them around the southern tip of Manhattan.

As early as 1829 the idea of a ship canal connecting the Harlem and Hudson rivers had been explored. If they could cut through the solid rock surrounding the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, the distance between the Hudson and Long Island Sound would be reduced by some twenty-file miles. More, 10 miles of new wharves could be added to the Manhattan’s new northern waterfront. And Manhattan would finally become a true island.

In 1863, the Hudson And Harlem River Canal Company was formed, still another effort to start the canal to join the Hudson and Harlem rivers with a navigable canal. But only in 1873 did the US Congress finally break the logjam by appropriating funds for a survey of the relevant area, following which New York State bought the necessary land and gave it to the federal government. In 1876, the New York State Legislature issued a decree for the construction of the canal.

But exactly where would the canal go? On March 3, 1881 Congress passed the River and Harbor act and called for a survey of possible routes for the proposed canal. (This might sound a familiar note that infrastructure legislation did not move expeditiously even then!) Several paths were considered. From an engineer’s perspective, the obvious choice would have been to blast through the south tip of the Bronx creating a straight line from river to river. But right here was the Johnson Ironworks, a major supplier of guns and cast ammunition to the US military, and that path would require condemning the major portion of its works and isolating the southern part. So, ultimately, it was decided that cutting through “Dyckman’s Meadows” would be the best option, and so the initial canal looped south of the foundry.

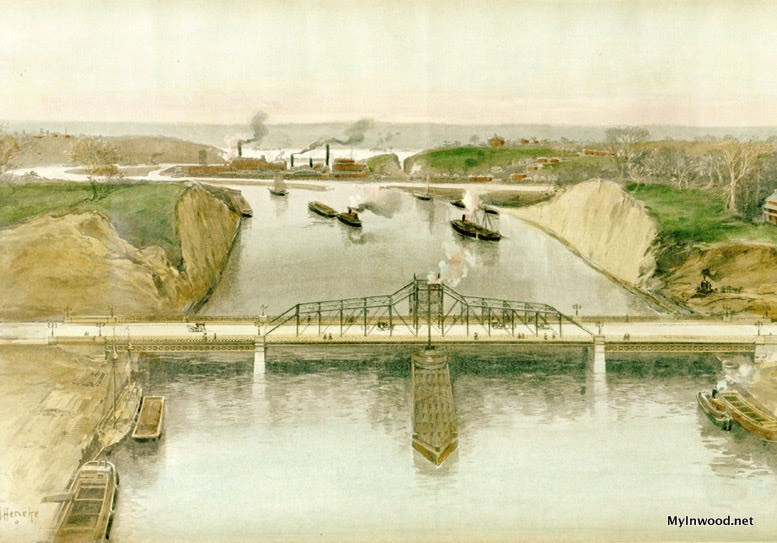

Construction of the Harlem River Ship Canal – officially the United States Ship Canal – finally started on January 9, 1888, when a group of some two hundred, mostly Italian laborers, set to work. To make the 1,200 foot cut the workers erected dams on either end of the Spuyten Duyvil–one dam at the eastern end of the small stream, where it emptied into the Harlem River, and another on the western end along the Hudson. Between these two man-made structures, designed to keep the water out, laborers blasted away the surrounding hills and burrowed through solid rock to create a channel 350 feet wide and 85 feet deep.

The work was dangerous and labor-intensive. Nor’easters caused extensive damage to the project, and destroyed the dams erected at the east and west ends to permit water-free excavation. Construction machinery was ruined by the flooding, and the canal was finished by dredging both the rock and the machinery away, while the drilling and blasting was done from that point on by underwater divers.

The canal opened officially in 1895. John Jacob Astor IV, one of the world’s richest men and a backer of the canal, who had speculated heavily on the real estate that the canal would improve into waterfront, was set on being the first man through it. However, three months prior to the opening ceremony a lowly steam tugboat – the Lillian M. Hardy – managed to traverse the entire route with its shallow draft, stealing his thunder.

The official ceremony, months later, would be opened by the U.S.S. Cincinnati firing a broadside to signal the opening of the Spuyten Duvil Bridge to ship traffic. A huge celebration took place, with hundreds of thousands showing up for the spectacle.

“The United States Cruiser Cincinnati, her brass guns shining brightly in the sun, lay near the New York shore, a little above the drawbridge, and around her the tugs and launches and the private yachts and excursion steamers collected, waiting for the signal to start…. The fleet of vessels made a pretty sight in the Hudson, waiting for the signal to start. The tugs, of which there were two dozen or more, were all profusely decorated with flags. The little steam and electric and naphtha launches puffed around here and there like brilliant-hued Croton bugs, while the Stiletto, the Now Then, the Vamoose, and other marine fliers cruised about on the western side of the river. The police steamer Patrol arranged the boats in the order in which they were to go throughout the canal.” (New York Times, June 18, 1895)

http:// Opening of Harlem Ship Canal, Harper’s Weekly, 1895.

For a while Marble Hill would be an island, but in 1916, part of the old creek was completely filled in, making the former island of Marble Hill physically contiguous with the Bronx. But in this case, possession wasn’t nine tenths of the law. Despite being physically in the Bronx, Marble Hill remained administratively part of Manhattan.

The Marble Hill story wasn’t over yet. In 1939, the Bronx borough president planted a borough flag and claimed it for the Bronx. The issue rattled around in court for decades (nothing moves quickly) until in 1984, the New York State Legislature permanently included Marble Hill as an administrative part of Manhattan.

In 1919, New York State passed a bill in order to straighten the western end of the canal feeding into the Hudson. Initially, it had been diverted south to avoid disturbing the Johnson Iron Works foundry. The foundry held out until 1923 when it vacated the premises, and in 1927 was awarded $3.28 million in compensation, just over a third of their original demand of $11.53 million. Plans to excavate the channel were finalized in 1935, and the channel was excavated from 1937 to 1938. The canal was now invisible, just a section of the Harlem River. The work severed the Johnson foundry’s 13.5-acre peninsula of land from the Bronx, and a piece of the Bronx was then absorbed into Manhattan’s Inwood Hill Park.

But there’s a still mystery. We know that the opening of the Canal was a very big deal on the Hudson side: “It was a great day for upper New York. The joining of the waters of the Hudson and East Rivers was celebrated as no similar event has been celebrated since the Erie Canal was opened in 1825.” (Newburgh Daily Journal, June 17, 1895)

But what about on this side? I find no information about celebrations on the East River as the flotilla of ships passed through the Canal and Harlem River and exited just north of our Island. Surely Island residents must have known about the Canal opening. Were they waiting to see the first ships emerge? Was there a celebration here?

New tasks for the renowned Roosevelt Island Historical Society!

Thanks for taking this trip with me.

Stephen Blank

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEEKEND PHOTO

S. KLEIN ON THE SQUARE

Lots of comments today about the S. Klein photo

O I remember that. The S Klein discount clothing store on Union Square

The dress company I worked for 3 summers in the 1960’s did hush-hush business with them

M. Frank

As the name on the building indicates this is one of the two S Klein on the Square Buildings. This building still exists as 24-32 Union Square East. The second and larger S. Klein building on Union Square occupied the corner lot at 14th Street and 4th Avenue (Park Avenue South).

When I worked for a home care company that was created by Roosevelt Island Residents with Disabilities we had an office at 853 Broadway which is across from the S Klein location. While working there, I witnessed the demolition of Klein’s and the replacement of that building with Zechendof Towers.

Ed Litcher

S Klein Department Store, 14th Street and 4th Ave. (now Park Ave. South).

Andy Sparberg

The Great S. Klein store on 14th Street. I remember seeing it for the first time as a youngster and insisting that it was owned by a favorite uncle, Manny Klein. I made such a nuisance of myself about this that I was taken to the restaurant that my uncle DID own and had a chocolate ice cream soda !

Jay Jabobson

Discount clothing on Union Square. My aunt bought her wedding dress there in the 50’s.

Harriet Lieber

Klein’s department Store. I lived down the street from Klein’s and loved searching for bargains for my new apartment in 1970.

Gloria Herman

Alexis Villafare, Hara Reiser, Laura Hussey also got it right.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

Sources

https://en.linkfang.org/wiki/Harlem_River_Ship_Canal

https://myinwood.net/the-harlem-ship-canal/

https://everything2.com/title/Harlem+Ship+Canal

http://www.washington-heights.us/spuyten-duyvil-creek-and-the-harlem-river-ship-canal/

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment