Monday, December 20, 2021 – FROM UPSTATE SARATOGA TO NEW YORK

MONDAY, DECEMBER 20, 2021

The 550th

Saratoga’s

‘Fanny the Flower Girl,’

Gotham Book Mart Founder

from NEW YORK ALMANACK

by Jaap Harskamp

Frances Steloff was the daughter of a Russian immigrant and itinerant rabbi who, in an age of rising anti-Semitism, was one of the early Jewish settlers in Saratoga Springs. The large family lived in dire poverty.

After the death of her mother, Frances was “informally” adopted by a wealthy Boston couple. Having run away from her foster parents, she made her way to New York, worked in a Brooklyn department store selling corsets, before establishing a tiny bookshop in Midtown Manhattan. On her death, after eighty-one years in the business, she was revered as one of America’s most influential booksellers and bibliophiles. Founder of the Gotham Book Mart, she turned her establishment into a center for avant-garde literature

Taking the Waters

Upstate New York mineral springs have been valued throughout American history for their medicinal properties. European colonists gradually obtained most of the springs from Indigenous People, and the habit of “taking the waters” to combat illness and promote health was recommended by colonial doctors. Boarding houses and hotels were constructed to accommodate an increasing number of visitors.

One of the first permanent dwellings in Saratoga Springs was built around 1776. An inn was constructed above High Rock Spring, and, in 1802, a tavern and boarding house was built by Gideon Putnam across from Congress Spring. This became the luxurious Union Hotel in 1864 and the 834-room Grand Union Hotel five years later.

Although spa activity had been central to Saratoga in the 1810s, by the 1820s the resort had hotels with great ballrooms, opera houses, stores and clubhouses. The Union Hotel had its own esplanade, fountain, and formal landscaping by then.

One regular guest to the springs staying at the impressive United States Hotel on Broadway was Joseph Bonaparte, the deposed King of Spain and elder brother of Napoleon. After defeat at Waterloo, Joseph had fled to America in 1816 and acquired the Point Breeze estate in Bordentown, New Jersey. It was his home until 1839 when he returned to Europe.

The house became famous for its gardens, extensive art collection of Flemish and Italian masters, and a library of some 8,000 volumes. Eager to encourage the fine arts in America, Joseph generously lent items for exhibitions to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and other places. He was instrumental in disseminating European culture and artistic knowledge to early nineteenth century Americans.

Thanks to its relative proximity to New York City, Saratoga Springs became the nation’s top upscale resort and tourist destination. With it, the town’s character changed. Not health, but pleasure became its major appeal. In 1863 the Saratoga Race Course was opened where members of the Vanderbilt and Whitney families brought their thoroughbred horses, watched the races, and shared in Saratoga’s hectic social life.

The town gained a reputation for its “gentlemen gamblers.” In 1870, John Morrissey built the casino in Congress Park and with his successor Richard Canfield helped make it the “Monte Carlo of America.” The presence of these men was accepted by locals as they played by the rules, supported various charities, and refrained from violence. That all changed when Arnold Rothstein, the “Grandfather of Organized Crime” and the “Brain” of New York’s Jewish mob, settled in town. Gambling soon became associated with gangland activities, especially during Prohibition. By the late nineteenth century, the Saratoga springs were being depleted by commercial use. Medical advances reduced the springs’ therapeutic appeal.

Anti-Semitism

In 1877 Saratoga became the center of a controversy that attracted nationwide publicity. Joseph Seligman was a Bavaria-born Jewish banker and railway investor, a prominent and politically influential figure. On June 13th, 1877, he and his family showed up at the Grand Union where they had holidayed on previous occasions.

Although still a prime resort, business had been slack in recent times. Owner Alexander Stewart and his manager Judge Henry Hilton (a jurist and entrepreneur) blamed the cause of decline on the presence of too many “Israelites” at the hotel; many customers did not wish to stay at a hotel that freely admitted Jews. When Stewart died in April 1876, Hilton decided to impose admission restrictions. Jews were barred from registering. Seligman was denied entrance to the hotel.

What seemed initially a mere feud between two powerful men, became one of the first widely publicized anti-Semitic controversies in the United States. In a headline set entirely in capital letters, the New York Times of June 19th, 1877, ran an article on “A SENSATION AT SARATOGA.” The case became a national topic of discussion. A group of Seligman’s friends started a boycott of the hotel, eventually causing its decline and demise. Other hotels nevertheless followed suit by posting notices such as “Hebrews Need Not Apply” and “No Jews or Dogs Admitted.”

Within a few years, the mass migration of Jews from Eastern European would begin, giving rise to a spike in American anti-Semitism. From 1880 to 1910 near 1.5 million Jews fled pogroms and violent discrimination in Russia and elsewhere.

One early Jewish settler in Saratoga was Benjamin Goldsmith who had arrived from Russia in 1865. He eventually operated a prominent cigar shop on Broadway. By 1910, the (Orthodox) Jewish community in Saratoga Springs consisted of some twenty-five mostly poor families who stuck together in a neighborhood full of boarding houses and cheap restaurants nicknamed “The Gut.”

Amongst the early Russian newcomers were Simon and Tobe Steloff with their children.

Flower Girl & Book Lover

Ida Frances (Fanny) Steloff was born on September 31st, 1887, the sixth of fourteen children in an immigrant family and the first to be born in America. Her father Simon was a dry goods peddler, itinerant rabbi, and Talmudic scholar who spent much of his time in meditation while his large family was close to starvation.

Fanny’s mother died in 1890. Simon immediately remarried and continued to have more children. One cannot cogitate all day. The stepmother was said to be a cold and indifferent character. Fanny’s younger years were recalled as difficult and dark.

Beneath their home’s single lamp, Simon would teach his sons to read from religious books he kept on his shelf. His girls looked on from the dark, not allowed to be part of the educational process. It filled young Frances with pain and envy, but also ingrained a deep love for books. For the rest of her life she would associate learning with “a circle of light.”

Taken from school at a young age to help in putting food on the table, Frances started selling little bouquets of flowers to the patrons who sat on the verandas of Saratoga’s grand hotels. Aged seven, she became known as “Fanny the Flower Girl.” She also took care of her younger brother who accompanied her on her trading rounds. A small and attractive boy, he received much attention and boosted her sales.

One day, a wealthy Boston couple expressed the wish to adopt her little brother (the informal procedure by which poor children were “farmed” out was common at the time). Simon refused to let his son leave, but offered one of his daughters instead. Pleased to escape her stepmother, Fanny left with her foster parents for Boston. Being used as a housemaid, she eventually ran away to New York City and never saw her adoptive parents again.

Having established herself, she began work at Frederick Loeser’s luxury department store in Fulton Street, Brooklyn, selling corsets. Once she was transferred to the book and magazine department to assist during the Christmas rush, she quickly found her niche. Her love for books had not died. Taking jobs and learning the trade in several bookstores, she slowly made her way up. By 1919, she was employed at Brentano’s, then the largest bookselling firm in the world.

One day in December 1919, while walking towards Times Square to see her sister who worked at the Hotel Aster, she noticed a “Shop for Rent” sign in the basement of an old brownstone. On January 2nd, 1920, in the middle of theater land, she opened her tiny Gotham Book & Art store on West 45th Street. As the district was also the center of the music publishing industry, the location proved a perfect choice. She soon built up a clientele of writers, artists, actors, and musicians. George and Ida Gershwin were amongst her first and most frequent visitors as their studio was on the same block.

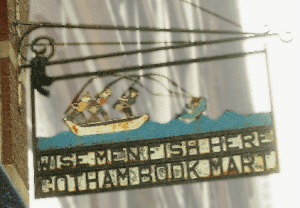

Wise Men Fish Here Steloff’s ‘Wise Men Fish Here’ sign in 2007

1923, planning permission was given for her building to be pulled down, forcing Frances to move her store to 51 West 47th Street. She changed its name to Gotham Book Mart (Gotham as a nickname for New York had been popularized by Washington Irving). Outside she displayed the iconic cast-iron sign “Wise Men Fish Here.”

Her customers remained loyal. John Dos Passos, H. L.Mencken, Theodore Dreiser, and many other prominent writers of the day followed her. The store continued to expand and gained a reputation for promoting the avant-garde.

Frances focused primarily on the “little” literary magazines of the day where many modernist writers would first publish their work. Steloff’s reputation reached Europe. She started to receive orders from T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and James Joyce. In return, she made every effort to supply their books to her customers, even if certain works were officially banned.

In order to smuggle Ulysses into the country, she arranged for friends in Paris to disassemble the books and mail them in gatherings. On arrival in New York these were sown back together again. Frances ordered Lady Chatterley’s Lover directly from D.H. Lawrence in Italy, arranging for customers to smuggle them in their luggage. She did the same with Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. Her disregard of and contempt for the censor resulted in a good deal of problems with the authorities. In 1936 she braved arrest for selling André Gide’s autobiography Si le grain ne meurt (If It Die).

Gotham Book Mart managed to survive throughout the Depression and the Second World War. Over a period of time, Frances acquired a long list of loyal literary customers. Christopher Morley, William Carlos Williams, Thornton Wilder, Marianne Moore, Anais Nin, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas, they all paid her a visit when they were in New York. Where possible Frances employed young authors. LeRoi Jones and Allen Ginsberg worked for a while at the Gotham. Tennessee Williams held his job as a clerk at the store for less than a day. Frances sacked him for being lazy and sloppy. The shop also functioned as a literary salon, hosting meetings of the James Joyce Society, organizing poetry readings, and holding exhibitions. It was a catalyst in the formation of the international avant-garde.

Frances was close friends with Edgar Stravinsky and his wife. When Edith Sitwell was in town she introduced the British poet to the composer and arranged tickets for her to attend a Stravinsky concert at Carnegie Hall. When Frances gave a party in honor of Jean Cocteau, the French author was accompanied to the occasion by Charlie Chaplin.

Having fled war-torn Europe in 1940, Henry Miller arrived in New York without a penny to his name. He turned to Frances for help. When on a brief vacation (she rarely left the premises of her bookshop) in New Mexico in the company of Georgia O’Keefe, she met Frieda Lawrence and other members of the literary commune gathered there.

In 1965 William Garland Rogers published Frances Steloff’s biography Wise Men Fish Here. That same year she received the gold medal from the Academy of Arts and Letters for her contribution to the arts. Fearing that she was slowing down, she sold Gotham Book Mart to her chosen successor Andreas Brown, the cataloger of John Updike’s manuscripts at Harvard University. The deal was struck in 1967, but Frances remained actively involved until her death, aged a hundred and one, in April 1989. Her career as a bookseller had spanned eighty-one years. Gotham Book Mart finally closed its doors in 2007.

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

Send your response to:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com.

If you get a bounce-back use jbird134@aol.com

WEEKEND PHOTO OF THE DAY

FROM FORGOTTEN NEW YORK

Now home to an ice cream franchise, this building, opened in 1926, was formerly used to berth fireboats and dry firehoses, hence the tower. On this spot, at the north end of Old Fulton Street where Brooklyn Heights meets DUMO in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, had been the elaborate Victorian Fulton Ferry Terminal; the ferry, connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan’s Fulton streets, began operating in 1814 by Robert Fulton’s ferry company and was discontinued in 1924. The building contained the offices for the harbor firefighting patrol until the late 1970s. (Contrary to popular belief, Fulton didn’t invent the steamboat, but his ship the Clermont established that it could be commercially viable.)

The opening of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 assured the decline of this and other ferries on the East River. Fulton Ferry service ended in 1924.

In addition, the Kings County Elevated Railway opened the line, from dual western terminals at Fulton Ferry and Brooklyn Bridge (Sands Street) east to Nostrand Avenue, on April 24, 1888. It was extended east to Albany Avenue on May 30, 1888. The line was further extended to Ralph Avenue on September 20, 1888 and completed to BMT Fulton Street Line at the west end of East New York in early November.

Service from Fulton Ferry ended May 31, 1940, and the Fulton Street el was gradually cut back until all of it was eliminated. Today’s A and C trains duplicate its route.

SOURCES

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARSKAMP

Illustrations, from above: Congress Spring, Saratoga, 1849; Morrissey’s Gambling House (later Canfield Casino) 1871; Saratoga Racecourse in 1907; the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga Springs; Lynn Gilbert’s iconic photograph of Frances Steloff in 1978; and Steloff’s ‘Wise Men Fish Here’ sign in 2007 (the year of the bookstore’s closure).

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment