Friday – Sunday, July 26-28, 2024 – STEP ON HISTORY EVERY DAY

NYC MANHOLE COVERS:

HISTORY AND HOW THEY’RE MADE

PART 1

UNTAPPED NEW YORK

ISSUE #1280

FRIDAY-SUNDAY, JULY 26-29. 2024

How many manhole covers are there in New York City? How are they made? Where do they lead to? In an episode of The Untapped New York Podcast we go over manhole covers 101 and discuss why New Yorkers find them to be such curious objects. We speak with Lisa Frigand, the former Manager of Cultural Affairs at the NYC Department of Environmental Protection, Natasha Raheja, an anthropologist at Cornell University who made the film Cast in India about how manhole are made, and with Justin Rivers, Untapped New York’s Chief Experience Officer, who will talk about his personal experience going down into a manhole. We’ll also look at a unique manhole cover art project that popped up in Greenwich Village. By the end of the episode, you’ll also have the answer to that famous interview question, why are manhole covers round?

If you look down on New York City’s streets, you’ll see quite a cacophony of things from manhole covers, to spray painted symbols, to crosswalks, and more. To kick things off, we first went out onto a Greenwich Village street with Justin Rivers to check out some manholes. The area around Minetta Street is a treasure trove for manhole cover hunters. In just about two blocks, you’ll find dozens of manhole covers for gas, water, sewer and the subway. Of particular note is a DPW manhole cover you’ll find on Minetta Street. If you shine a flashlight down one of the open holes on the cover, you can see the former Minetta Brook flowing. This former fresh-water source for New Yorkers has been long buried and connects into the sewer system now. DPW stands for Department of Public Works, a predecessor of the NYC Department of Environmental Protection. It’s just one of the many abbreviations you’ll find on NYC manhole covers.

A look at the Minetta Stream down a manhole

On Minetta Lane and the vicinity, you’ll be able to trace the evolution of the NYC Sewer manhole cover from a late-Victorian DPW manhole cover with ornate lettering, to a more industrial DPW manhole cover, to the classic NYC Sewer manhole cover, to one that is also “MADE IN INDIA,” as well as one that simply says “SEWER.”

On Minetta Street, a NYC Sewer Made in India manhole cover sits next to a more old-school DPW manhole cover

Each manhole cover is a portal to an underground world below. In popular culture, what lies beneath has been explored repeatedly, perhaps most notably by the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, who would pop a manhole cover to go down to their underground lair that they shared with Splinter, the mutant rat who raised them. The NYC Sewer manhole cover also doubled as a weapon.

Popular fascination with underground systems continues to be manifested in the websites of urban explorers, writers and photographers. This enthrallment can be attributed in part to the rich mythological origins of a fabled underground. In Greek and Roman mythology, Hades is an underground world of arrivals, transition, and temporality. Even if we don’t think of the world under New York City’s streets as a place for lost souls, manholes still remain as a portal between the city as us mortals experience it and the underbelly that supports our existence.

The earliest manhole covers you can find in cities are usually coal hole covers. Made of cast iron, they are generally square or rectangular in shape, sometimes hexagonal. They led to former coal chutes in residences and commercial buildings. Although coal is no longer used to heat homes, you can still find coal hole covers in some of New York City’s oldest districts, like Brooklyn Heights.

But the round manhole covers that most people think of are usually connected to essential services like water, sewers, and power. The advent of modern urban existence in the 1800s necessitated the removal of these services underground. It was part functional but also a utopian ideal, intended to preserve the beauty of cities.

The word “sewer” is defined in old English as “seaward,” which described the open drainage ditches that sloped downwards to the Thames River. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the origin of the word sewer to the old French word seuwiere, meaning “a channel to drain overflow.” By the nineteenth century, the waste from these conduits in all the major cities eventually overwhelmed the ability of natural bodies of water, like rivers and ponds, to self-cleanse. London experienced what is known as “The Great Stink” of 1858. The particular potency of the pollution that summer shut down government and prompted lawmakers to finally enforce and enact public health legislation.

Baron Georges Haussmann, who is credited with laying out modern Paris wrote in 1854, “The underground galleries, organs of the large city, would function like those of the human body, without revealing themselves to the light of day. Pure and fresh water, light, and heat would circulate there like the diverse fluids whose movement and maintenance support life. Secretions would take place there mysteriously and would maintain public health without troubling the good order of the city and without spoiling its exterior beauty.”

New York City was going through something similar. Like all early settlements, New Yorkers initially relied on existing bodies of water for fresh drinking water. Collect Pond is the most famous, located near the courthouses in Lower Manhattan today. The nearly 50-acre lake was the main source of drinking water, fed by an underground spring. But polluting industries like slaughterhouses, breweries, and tanneries built along the pond’s shores contaminated the water and eventually, the pond was filled in.

By 1811, the natural landscape around Collect Pond was gone and the relentless march of development continued even atop this poorly engineered and polluted landfill. The rough and tumble neighborhood built at Collect Pond became known as Five Points — immortalized in the Martin Scorsese film Gangs of New York. Things got so disgusting with sewage and industrial runoff, they actually had to fill Collect Pond in. A canal was created to drain the pond, but it too became an open sewer and had to be filled in. That’s how Canal Street got its name.

One of the public health crises that emerged from contaminated water was cholera. The first wave of cholera in 1832 killed 3500 New Yorkers. Adjusted for population, that would be equivalent to 100,000 New Yorkers losing their lives in 2020, which is nearly four times the current death toll of COVID-19 in New York City. New York would be hit with four more waves of cholera through 1866, some even deadlier than first wave, making it one of the most disastrous epidemics in New York City’s history.

PART 2 CONTINUES NEXT WEEK

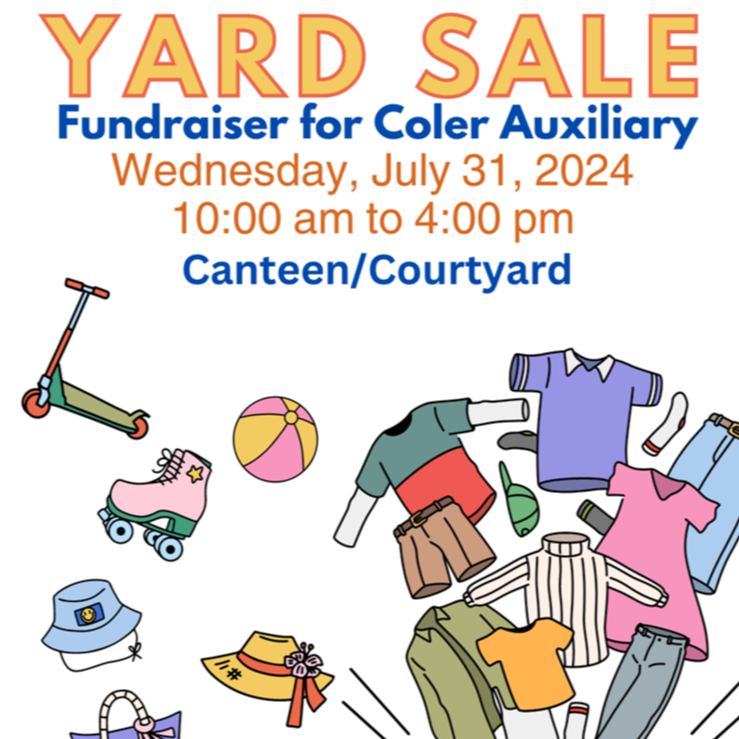

ALL PROCEEDS WILL GO TO SUPPORT THE AUXILIARY PROGRAMS

CREDITS

NYS Music is New York State’s Music News Source, offering daily music reviews, news, interviews, video, exclusive premieres and the latest on events throughout New York State and surrounding areas. Subscribe to their newsletter here.

Illustrations, from above: Tin Pan Alley in 1905; Abraham Lefcourt, June 1927 (courtesy Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University); The Brill Building in 1931; The Brass Portrait bust of Alan E. Lefcourt above the Brill Building’s entrance; and a young Paul Simon and Carole King in the Brill Building, 1959.

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment