Wednesday, August 14, 2024 – HOW ART INFLUENCED THE GREAT MIGRATION

IN THE STEERAGE

OF THE

GREAT ATLANTIC MIGRATION

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 14, 2024

Issue # 1286

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARKSKAMP

In the Steerage of the Great Atlantic Migration

August 12, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp

Painter George Benjamin Luks was born in August 1867 in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. According to the 1880 census, his father was Polish and his mother born in Bavaria. The family then moved to the coal mining borough of Pottstown, Montgomery County, PA, where his father worked as a physician.

Living in the midst of a community of struggling Eastern European families, Luks was directly confronted with the toughness of the immigrant experience. It would determine his career as an artist.

In the Steerage

Luks began his studies at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Dissatisfied with the conservative standard of teaching, he left for Europe and spent time in Düsseldorf (a number of American painters had received their training at the city’s Art Academy). He visited London and Paris.

On his return in 1893 he became an illustrator for the Philadelphia Press. Meeting at John Henri’s studio, Luks was a member of the “Philadelphia Five” (with John Sloan, William Glackens and Everett Shinn). These painters rejected the “genteel” approach of contemporary artists and turned to the harsh depiction of ordinary life.

In 1896, Luks moved to New York City where he was employed as an illustrator by the New York World. A tough character, he embraced the gritty side of the metropolis in art and life.

His former Philadelphian associates had also settled in the metropolis and encouraged him to further explore his painted themes of “New York Street Life.” He joined a group of artists (later referred to as the Ashcanners) who rebelled against conventional academicism and “pleasing” impressionism.

These painters believed in the worthiness of working-class life as artistic subject matter. An urban realist, Luks focused on cityscapes and street scenes. In a series of paintings he captured the energy and hardship of the tenement districts and their occupants.

In 1900, in the middle of a period of mass movement from Europe to the United States (the Great Atlantic Migration) Luks created “In the Steerage,” a painting in which he depicted a group of migrants lined up against the rail of an ocean liner arriving in New York Harbor after an arduous voyage across the Atlantic. Migrants tended to crowd on deck once the Statue of Liberty was sighted.

Steamships made their first stop at a pier on the mainland. There, First and Second Class passengers were free to disembark without medical checks or personal questioning. Afterward, steerage passengers were crowded onto a barge or ferry and taken to Ellis Island (the “Island of Tears”) for inspection and examination.

In bold colors and brushwork George Luks communicates an emphatic image that reflects both the exhaustion of a long stay in steerage and the anxiety about what the future may hold.

Precarious Passages

The steerage was located immediately below the main deck of a sailing ship where the control strings of the rudder ran. In the early days of migration passengers were placed in the cargo hold where temporary partitions were erected to accommodate people and livestock. As soon as a ship had set its passengers on land, the furnishings were removed and preparations made for a return cargo of cotton or tobacco to Europe.

Early steamships of the 1830s and 1840s were expensive to run and only attracted those travelers who could afford the fare. The Irish Potato Famine and the repression that followed the failed 1848 uprisings in Europe, forced many families to flee in search of a new beginning. Within a decade, a huge migrant market was created. Fledgling ocean liner companies competed to exploit the opportunities offered by this desperate mass of humanity.

The transport of boat people (“self-loading cargo”) became a money-spinner as some steamers could hold over 2,000 passengers in steerage. Carrying them in the cheapest manner was enormously profitable. The word steerage now began to refer to the lowest category of long-distance travel. Destitute migrants needed to make the transatlantic crossing at minimum cost.

Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson had sailed in 1879 from Glasgow to New York to research “Steerage Types” and give his travelogue The Amateur Emigrant a sense of authenticity (the book was not published until 1895).

He described a very uncomfortable journey in company of the poor and sick, supplying an abundance of details about bedding arrangements, food rations, etc. In 1906, American investigative reporter Kellogg Durland sailed as a steerage passenger and delivered a blistering attack on the miserable state of affairs on board.

In a cut-throat market, the price of transatlantic travel was made affordable to even the poorest travelers, but conditions were atrocious. Crammed in cargo holds, migrants were treated as cattle. They slept in rows of shared bunks on mattresses filled with straw or seaweed. On stormy days, all hatches were sealed to prevent water from getting in, making the already stuffy air below unendurable. For millions of migrants, steerage conjured up images of squalor, abuse and disease.

Passengers had to bring their own food for the duration of the voyage, which could last as long as three weeks. Many starved to death during the voyage, their corpses flung over the side. Infectious disease (cholera and typhus; measles among children) was another cause of high mortality.

Early ocean liners were a new generation of slave ships. British and American governments introduced (advisory) legislation in the 1850s to prevent overcrowding, provide toilet facilities and guarantee rations of food and water, but ship owners responded slowly and reluctantly.

The migration statistics in the period between 1860 and 1914 are staggering; some fifty-two million people left different parts of Europe for America. It was the intensity of competition for a share of the lucrative market and not government intervention that forced upgrades.

Liners became bigger, faster and more refined. Because of negative connotations, companies re-marketed steerage as Third Class, but the journey remained a testing experience.

SS Kaiser Wilhelm II

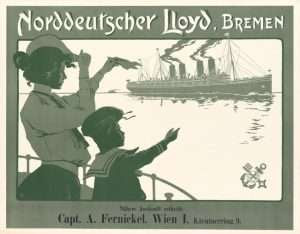

With the rise of a global travel industry, rival companies started competing with each other to make fast and luxurious crossings. Oceanic transportation boomed. To reach New York in record tempo was a race for glory and customers. Bremen-based Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL) became one of the largest shipping companies in the world.

Its liner Kaiser Wilhelm II was launched at Stettin in August 1902 in the presence of the German Emperor and joined her sister ships on a scheduled service between Bremen and New York City. In 1904 she won the “Blue Riband” for the fastest eastbound crossing of the North Atlantic.

Offering berths to 1,888 passengers, the ship’s interior was designed by Bremen’s most prominent architect Johann Poppe. He turned the liner into a floating Grand Hotel with a range of stylish amenities for affluent passengers. The First Class dining saloon was three decks high and decorated in German (Bremen) Baroque revival style. Displaying a life-size portrait of the Kaiser, it could seat 554 diners.

The golden age of ocean travel in the early twentieth century coincided with the emergence of the illustrated poster. Advertisers were driven to outdo their competitors with ever more appealing imagery. Shipping companies employed graphic artists to visualize leisure and modernity. Promotional posters transformed long distance travel into an alluring experience in the public imagination.

Glamour would remain central to promoting the image of ocean liners throughout the 1920s, although in reality these ship served the needs of a diverse public. NDL’s flagship Kaiser Wilhelm II mirrored society’s inequalities by offering extremes of luxury and comfort to a minority of wealthy travelers, whilst transporting large numbers of poor emigrants under the most basic of circumstances.

Edward Alfred Steiner was a Professor of Theology in Grinnell College, Iowa. Born into a Jewish Slovak-Hungarian family and educated in Vienna and Heidelberg, he had settled in the United States in 1886. He penned a number of books in which he detailed the experiences of immigrant Jews (although he had converted to Christianity himself).

In 1906, Steiner published On the Trail of the Immigrant in which he described the conditions in the steerage aboard SS Kaiser Wilhelm II where nine hundred passengers were packed like cattle. The flow of air was blocked, creating an unbearable stench.

A division between sexes was ignored, which meant that young women quartered among married passengers lacked privacy and protection. The food was miserable. Steerage on the world’s most prestigious ocean liner had barely improved.

Slumming at Sea

According to the Oxford English Dictionary the word “slumming” was first used in 1884 to refer to an increasing number of people who visited London’s poorest areas for either social observation or out of curiosity. By the 1890s the idea of “slumming it” in the East End had become a pastime for wealthy youngsters. The sight-seeing mania soon reached New York City. It was taken to sea as well.

First Class passengers would lean over their promenade deck railing and throw candy and pennies to children on the deck below. Slumming from above meant mixing with steerage passengers.

One of these slummers was photographer Alfred Stieglitz. In the spring of 1907, he and his family boarded the Kaiser Wilhelm II to visit relatives and friends in Europe. His wife Emmeline demanded luxury and Alfred purchased First Class tickets for their week-long passage on her account.

Once at sea, Stieglitz hated the stifling snobbishness of the quarters. He preferred to spend time at the end of his deck from where he could observe the crowd confined below. To his photographer’s eye, the ship’s steerage provided a framework for recording a moment of human drama. Using a hand-held Auto-Graflex camera with glass plate negatives, he captured the scene in a single picture.

Alfred was not able to develop the plate until he arrived in Paris and kept the photograph in its original plate holder until he returned to New York several weeks later – and put it aside.

Four years later “The Steerage” was first presented to the public when Stieglitz published the image in a 1911 issue of Camera Work devoted exclusively to his “new” style photographs, together with a Cubist drawing by Pablo Picasso. It then appeared on the cover of the magazine section of New York’s Saturday Evening Mail (April 20, 1912).

In 1913 “The Steerage” had its gallery debut, coinciding with the momentous Armory Show which introduced international avant-garde art to New York (George Luks was also well represented at the exhibition). Stieglitz intended to demonstrate that his photographs could rival the European vanguard.

Widely praised as a modernist masterpiece (Picasso was an admirer), “The Steerage” emboldened him to put his photography on a par with Cubist painting.

Golden Door & Returned Cargo

Stieglitz’s photograph captured the so-called steerage promenade. Every day at the same time passengers were herded on deck for their quarters to be cleaned. First Class travelers gathered on the upper decks to observe the spectacle. Looking at “The Steerage,” the photographer invites us to peek at the mass of migrants below. We are all invited to turn into slummers.

Stieglitz was aware of the fierce debates about immigration at the time and the ghastly treatment to which steerage passengers were subjected. His own Jewish father had joined the mass exodus from Germany, arriving in America in 1849 and making a fortune in the wool trade, but the photographer had mixed feelings about immigration.

Sympathetic to the plight of new arrivals, he objected to admitting the uneducated and marginal to the United States. Stieglitz may have felt for his subjects, but he denied that his work contained a statement. He was not promoting a social cause. He claimed that his only concern was to advance photography as a fine art.

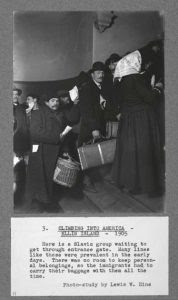

At the time, the immigration service channeled millions of arrivals through the “Golden Door” of Ellis Island’s main inspection building, but some twenty percent of incomers were detained for health or legal reasons. Some recuperated sufficiently to enter America, but others were returned to their homelands.

When Stieglitz took his famous shot, the Kaiser Wilhelm II was sailing on its return journey from New York to Europe. It is a visual record of people who had been turned away by officials for reasons of ill-health, “moral disease” (that is: politically suspect), old age or excessive poverty and forced to go back home (the criteria for refusal were summarized in the 1907 Immigration Act, signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt).

How can one interpret this photograph other than as a critique of migration policies? Stylistic mastery reinforced the message, but questions remain. Were all passengers in this photograph to be considered “returned cargo”?

Being sent back from Ellis Island even more destitute than they were on the day of departure, what happened to these lost souls once they had disembarked in their countries of origin? Information is scarce, history has kept silent.

IN THE RIVERCROSS DISPLAY WINDOW

CHECK OUT THE SIX PAINTINGS

BY YVONNE SMITH

SMITH WAS A RESIDENT OF GOLDWATER HOSPITAL,

A SELF-TAUGHT ARTIST. THESE ARE SOME OF HER

DOZENS OF PAINTING

CREDITS

Illustrations, from above: Robert Henri’s “Portrait of George Luks,” 1904; George Luks’ “In the Steerage,” 1900 (North Carolina Museum of Art); Fritz Rehm, poster for the Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL), 1903; Alfred Stieglitz’s “The Steerage,” 1907; and Lewis Hine’s “Climbing into America, immigrants at Ellis Island, 1905” (The New York Public Library).

JUDITH BERDY

NEW YORK ALMANACK

WE WILL BE TAKING SOME TIME OFF AND WILL RE-APPEAR OCCASIONALLY THIS MONTH. SEE YOU IN SEPTEMBER…

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment