Wednesday, August 21, 2024 – WOMEN FOUGHT TO FEED THEIR FAMILIES

Women’s War on Greed:

Inflation & Food Riots

WEDNESDAY & THURSDAY,

AUGUST 21-22, 2024

ISSUE # 1290

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARSKAMP

Women’s War on Greed: Inflation & Food Riots

August 20, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp

In the history of public disturbances, food riots were a recurring form of collective action. Initially, most “bread riots” were non-violent demonstrations restricted to the marketplace as the production and supply of food were local matters. Participants argued with their bakers trying to force them to sell their products at a “just” price.

Harvest failures happened regularly and shortages were common, but sudden price rises that deprived people of basic provisions were blamed on authorities for failing to protect their constituents. A “moral economy” dictated that markets should be run for the benefit of people. To exploit customers was similar to looting. Profiteering by hiking prices in a period of dearth (greedflation) was considered a criminal act.

During World War I, hunger hit civilian populations worldwide as agriculture and food distribution were disrupted. Riots took place in Vienna, Amsterdam Petrograd, Melbourne, Tokyo and elsewhere.

The crisis also hit Rhode Island. To the anger of its large Italian population, pasta prices increased by sixty percent. The “Macaroni Riots” (also known as The Federal Hill Riots of 1914) started in August in Providence when raucous residents attacked the premises of wholesale trader Frank Ventrone, a fellow Italian immigrant.

From the outset, food disturbances wherever they took place have had one feature in common: women stood in the forefront of agitation.

Marching Women

Paris had set a precedent. For centuries, bread was a staple of French diet and a symbol of national pride. Feeding the fast growing capital became a challenge. The city’s insatiable demand for foodstuffs led to the exploitation and exhaustion of the agricultural hinterland. A series of poor harvests intensified food-insecurity. High bread prices and supply shortages in Paris during the 1770s sparked outrage.

In late April/May 1775, hunger set off an explosion of popular anger in the towns and villages of the Paris Basin. Over three hundred incidents of theft and violence were recorded. The uproar became known as the “Flour War.”

The tension simmered in subsequent years and boiled over again on the morning of October 5, 1789, when groups of women protested against soaring bread prices. They were joined by large numbers of hungry and disgruntled other protesters. Together they marched towards the Palace of Versailles.

The unrest quickly became intertwined with the activities of revolutionaries seeking political and constitutional reforms. Rioters ransacked the city armory for weapons, before the crowd besieged the palace. The Women’s March on Versailles was an early and significant event leading up to the French Revolution as armed Parisian women rallied together to demand the intervention of King Louis XVI himself.

This statement of female independence disrupted social conventions that confined women to their “duties” at home, whilst caring for husband (the “breadwinner”) and children. This realization sent shock-waves through the political establishment, fanning fears that food riots might ignite demands for social change. The threat of a hungry “mob” was to be met with force.

Flour Riot

Demands for fair prices tended to include accusations of hoarding and price-gouging by traders. Political authorities were attacked for being in cahoots with business elites. More often than not, food riots were fueled by the fury about economic mismanagement and political corruption. What may have started as a spontaneous protest would soon be marshaled by members of community groups or trade unions and others. That was the case in the city of New York’s Flour Riot of 1837.

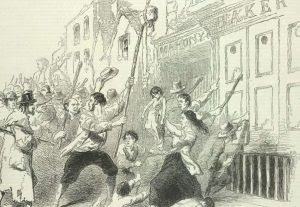

The disastrous Great Fire in 1835 was followed by a period of economic hardship and food shortages. The city was starving. On February 13, 1837, a meeting was called to protest against the price of flour and grain which speculators had driven up to twice their normal price. A crowd of 6,000 people was stirred up by the eloquence of political agitators.

Rumors were circulating. Word was spreading that the firm of Eli Hart & Co., a large brick building in Lower Manhattan owned by a Troy firm, was hoarding barrels of flour in order to inflate its price. Rioters marched up to its premises between Dey Street and Cortlandt Street. They ransacked the store by dumping 500 barrels of flour and 1,000 bushels of wheat outside its doors. Standing knee-deep in spilled flour and wheat, women collected the priceless spoils from the pavement.

The rioters then took down a second flour warehouse, that of S.H. Herrick & Co at nearby Coenties Slip, before being brutally dispersed by members of the New York State Militia. The mayhem was quelled by blunt muscle power. The use of violence did not stop people from protesting in times of need. Bread and flour wars were followed by meat conflicts. (You can read a first hand account here.)

Kosher Manhattan

Newcomers to the United States brought their own culinary practices with them, whilst acquiring the nutritional customs of their place of settlement. The migrant inhabits two worlds. Traditional “home” recipes are part of a heritage that will be nostalgically conserved, but modification to availability is always necessary and inevitable.

From the mid-nineteenth century onward, Manhattan’s Lower East Side was home to large numbers of German immigrants. Known as Kleindeutschland (Little Germany), its community was as diverse as the home nation itself before unification in 1871. By creating a social space in the process of adaptation, hundreds of local saloons and beer gardens played a formative role. Nostalgia was a good lunch, a reminder of home.

Erected in 1863, the brick tenement at 97 Orchard Street – which is today home to the Lower East Side Tenement Museum – had five stories and was designed (its architect is not known) to house twenty families in three-room apartments, four on each floor. The average household contained seven or more people.

On November 12, 1863, Bavarian-born Johann (John) Schneider and his Prussian wife started running a lager beer saloon from the basement of this building. The couple lived in a bedroom adjoining the beer hall’s kitchen. The Schneiders advertised the opening of their business with the promise of a buffet consisting of pretzels, sausages, pigs’ feet and sauerkraut.

Two decades later the ethnic composition of the district was changing rapidly. In 1881 the relatively liberal-minded Tsar Alexander II was assassinated in Russia. The ascendance to the throne of his reactionary son Alexander III initiated an era of relentless pogroms and persecutions that made living conditions for Russian Jews intolerable, leading to mass emigration between that year and 1914.

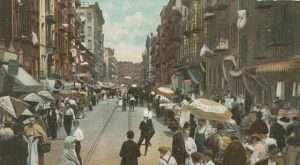

The Lower East Side became the destination for millions of Eastern European Jews, the crucible of a new life in New York City. It was the “goldene medinah” (promised land) for those fleeing oppression. Four out of five descendants trace their roots to this pivotal neighborhood.

By the turn of the twentieth century Schneider’s saloon had given way to Israel and Goldie Lustgarten’s butcher’s shop (one of 131 kosher butchers in the area at the time). The family hailed from town of Stanislau in Galician Poland (then under Austrian rule).

Sometime in the early 1880s, Israel, his wife and six children left the city and made the long journey to New York. His presence in Orchard Street was brief. During a local riot that took place in May 1902 the front window of his shop was smashed. Soon after he appears to have gone out of business.

Meat Boycott

At the beginning of 1902, wholesale meat prices began to climb. Jewish butchers were the first to feel the heat, because kosher meat was more expensive. Prices had to reflect not only the wages of slaughterers and religious supervisors, but also the cost of transporting live cattle to the city of New York in order to conform to Jewish dietary law (kashrut).

In May 1902, butchers had staged a shutdown to pressure slaughterhouses and wholesalers into lowering their rates, but they were unable to force price reductions. Their customers accused them of price gouging. The majority of Russian and Eastern European immigrant families in the Lower East Side (then the nation’s most densely populated neighborhood) could no longer afford to buy the staple.

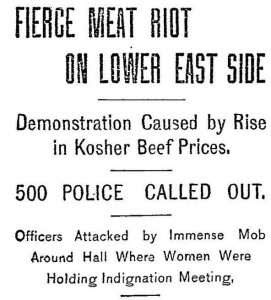

On May 14, 1902, as the price of kosher meat had jumped from twelve to eighteen cents a pound, mother of four Sarah Edelson called a meeting of local housewives at the Monroe Saloon in Monroe Street to discuss the crisis. Some five hundred people showed up, a much bigger turn-out than expected and the mood was angry.

Fanny Levy, one of Sarah’s neighbors and co-organizer, called for action and take on the might of the Beef Trust. It was decided to boycott butchers until they would reduce the price of beef.

The next morning some 3,000 women had assembled. Calling themselves the Ladies Anti-Beef Trust Association, its ad hoc membership split up in groups and picketed the kosher butcher shops in the Lower East Side and parts of Harlem and the Bronx, handing out leaflets that bore the image of a skull and crossbones and carried the slogan: “Eat no meat while the [Beef] Trust is taking meat from the bones of your women and children.”

Although many of the women had been in the United States for only a relatively short time and may not have managed much English, they made their collective voices heard. They felt angry enough to assert what they considered their newly gained American rights: the right to speak freely, protest publicly and demand fair prices.

Inevitably, there were violent scenes. Customers who ignored the pickets were heckled, pushed and pummeled; their parcels seized and the meat hurled into the gutters. Butchers who refused to shut their premises were attacked; their tools destroyed; their windows and fixtures smashed.

In trying to break up the protest, the police used brute force. Many participants were hurt or wounded. Eighty-five people were arrested and fined, three quarters of them women.

Meat & Monopoly

Three weeks into the boycott, the Beef Trust (temporarily) lowered the price for a pound of kosher meat by four cents. Although the event made controversial headlines in the press, the action highlighted the ability of (Jewish) women to organize and coordinate a movement throughout the boroughs.

The boycott would become a model for future protests (such as the 1907/8 rent boycotts) and was in many ways a precursor to larger scale strikes.

The basic problem was to identify the culprits who were responsible for the food crisis. Trapped in a cycle of scarcity and price rises, protesters aimed their anger at local suppliers who were as helpless in the process as their customers. On their side, butchers blamed the high cost of meat on “greedy” slaughterhouses. The root of problems however lay many miles away from Manhattan.

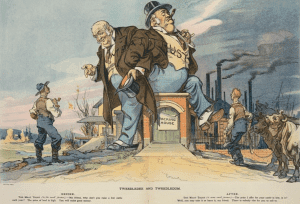

In an era of emerging trusts (companies banding together to control markets and fix prices), Chicago’s Beef Trust was one of those mighty cartels that held a stranglehold on the American marketplace until they were ruled illegal by the Supreme Court in 1905. Dominating the nation’s supply of meat products, it imposed steep price rises that were passed on to hundreds of Manhattan’s retail kosher butchers.

With the proliferation and intensification of commercial activity, food had become part of a free market system in which individuals had no agency. The traditional chain of food supply had been broken and become “invisible.”

What was once arranged locally, was now determined centrally; the community transformed into an economy. The market decided. The word no longer referred to a fair of shopkeepers and stallholders, but was applied as a euphemism for the most ruthless forces in the economic system.

Market meant the power of money. The concept of morality was deleted from economic theory.

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

“Illustrations, from above: Hungry people in Dungarvan, County Waterford, Ireland, attempt to break into a bakery during the Great Famine (The Pictorial Times, 1846); The “Ventrone Block” on Atwell’s Avenue, Providence, in 1910 (Providence Public Library); illustration of the Women’s March on Versailles, October 5, 1789; illustration of the Flour Riot 1837; Little Germany in Manhattan in the late 19th century; Jewish life in the Lower East Side; the 1902 Manhattan meat boycott covered in the national press; and “Tweedledee and Tweedledum” anti-Beef Trust cartoon (Udo J. Keepler, 1913). The text reads Before. The Meat Trust (to the small farmer): My friend, why don’t you raise a few cattle each year? The price of beef is high. You will make good money. After. The Meat Trust (to same small farmer): The price I offer for your cattle is low, is it? Well, you may take it or leave it, my friend. There is nobody else for you to sell to.”

PHOTO OF THE DAY

LITTLE FREE LIBRARY BOX

LOCATED BY THE RIVERCROSS LAWN

BRUCE BECKER, DEVELOPER OF THE OCTAGON HAS RECENTLY OPENED THE MARCEL HOTE IN NEW HAVEN. THIS HOTEL IS USING FULLY SUSTAINABLE WAYS TO OPERATE.

CHECK OUT THE YOU TUBE VIDEO FROM LAST SATURDAY’S “CBS SATURDAY MORNING”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wea23LTmeMo

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment