Weekend, August 30 -Sept 1, 2024 – THE EAST MIDTOWN PROMENADE TO BE LENGTHENED

THE SCOTTISH-AMERICAN

PIONEER AT

BELLEVUE HOSPITAL

ISSUE # 1295

NEW YORK ALMANACK

By JAN HARSKAMP

A Scottish-American Pioneer at Bellevue Hospital

August 29, 2024 by Jaap Harskamp Leave a Comment

Bellevue Hospital is considered the oldest public hospital in the United States. Although its historical beginnings date back to Dutch settlement in the 1600s, the institution was officially founded in 1736 by the British on the second floor of a poorhouse, four decades before the outbreak of the American Revolution.

In spite of its contribution to the development of medical care in the metropolis, the hospital’s name occupies a dim place in New York City’s collective consciousness. In the later nineteenth century, the institution struck fear and disquiet in the hearts of New Yorkers. A grim sight on 1st Avenue and 26th Street, Bellevue was synonymous with degradation and death.

When a psychiatric unit was added to the hospital in the 1930s, its dire reputation grew even darker. An eerie red brick structure surrounded by an iron spiked fence, it inspired nightmare tales and horror films.

Most of the hospital’s Manhattan history has been recorded, but a strong Scottish connection with its early development needs further emphasis.

Infamy & Innovation

At the time of New York City’s massive expansion, Bellevue Hospital was overrun with victims of epidemics, homeless people, alcoholics, abandoned children and patients ranging from the suicidal to the homicidal.

Overcrowded and understaffed, conditions were abysmal. Antiseptic practices were poor and filthy surgical theatres not fit for purpose. In 1876 it was reported that nearly half of all amputations proved fatal due to a poor and ill-equipped working environment.

When in 1879 Harpers New Monthly Magazine ran an article on New York hospitals, it described Bellevue as serving the poorest of the poor, the dregs of society and the semi-criminal. Its wards were “filled with wasted souls drifting through the agonies of disease toward unpitied and unremembered deaths.”

Its numerous alcoholic inmates were transported to the asylums of Blackwell’s (now Roosevelt) Island, lying in sight from Bellevue up the East River.

For all this infamy and maybe because of it, Bellevue was also a pioneering place. It played a vanguard role in the battle against major epidemics, such as tuberculosis, typhus and yellow fever. It was the first American hospital to run a maternity ward; it established a nursing school (1873) and ran a children’s clinic, apart from playing a leading role in the search for new and effective medicines.

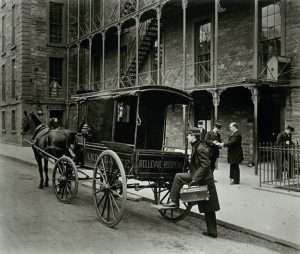

During the Civil War, the United States Army sent many of its wounded back there for medical care. Surgeon Colonel Edward Barry Dalton, a veteran of the conflict, had himself witnessed the urgent need to send injured soldiers for professional treatment as speedily as possible.

He introduced what is believed to be the first functioning ambulance in the city of New York, a horse-drawn wagon with removable slatted beds in the back, replete with medical equipment, morphine and brandy.

Wall of the Unknown Dead

In 1866, New York’s first professional morgue opened on the grounds of Bellevue Hospital. The term morgue is Old French for face or visage. Over time the word was applied to the space where unclaimed dead bodies awaited identification.

During the later nineteenth century, the Paris morgue was located on the Quai du Marche-Neuf, just behind Notre Dame. Two-thirds of the corpses that entered the building

were retrieved from the Seine, being suicides, drownings or murders.

The morgue’s assistants methodically noted down the particulars of each corpse. The naked bodies, often in a horrible state of decay, would be displayed for three days on twelve brass-lined stone slabs propped up in the morgue window for the public to view and possibly recognize. This showcase became a piece of entertainment in Paris. People of all ages would visit the famous windows of death.

As both an object of macabre fascination and a theme of the new literary vogue for sensational subjects, the Paris mortuary bewitched the Victorian imagination. Thomas Carlyle, Frances Trollope, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Charles Dickens, Walter Pater and many others left accounts of their visits.

When living in Paris in 1855/6, a trip to the morgue inspired Robert Browning’s dramatic monologue “Apparent Failure,” a moralistic poem about suicide.

Bellevue on the East River followed the Parisian example, but its staff made an interesting addition.

In 1867, the hospital established a Photographic Department where Oscar Mason (ca. 1830 – 1921), a thirty-seven-year-old portrait photographer, took pictures of anonymous corpses and hung them up for family or friends to identify the body. Mason established what New Yorkers would label as the “Wall of the Unknown Dead.” He subsequently created early criminal mugshots modeled after the Wall.

The Bellevue psychiatric hospital was erected on hospital grounds in 1931, a few blocks to the north of the main hospital on 1st Avenue. This haunting structure was once home to Mark David Chapman, on the night he shot John Lennon. Charlie Parker, Allen Ginsberg, Eugene O’Neill, William Burroughs and Sylvia Plath all stayed here at one point, as did Norman Mailer after he stabbed his wife.

The population of people who used its mental health facilities peaked in 1955 at 90,000. For locals, Bellevue was the end of the road. It was Manhattan’s Bedlam. So how did it all start?

An Early American Illustrator

Alexander Anderson was born to Scottish immigrant parents on April 21, 1775, near Beekman Slip, Manhattan, two days after the first bloody battle in the American War for Independence had taken place at Lexington and Concord. Many Scottish-Americans supported the Revolution, be they statesmen, soldiers or citizens.

Two signers of the Declaration of Independence, John Witherspoon and James Wilson, were of Scottish descent and so was naval hero John Paul Jones.

Alexander’s father John Anderson was a “rebel” printer and publisher of a newspaper called The Constitutional Gazette which opposed James Rivington’s loyalist Royal Gazette. He was also responsible for printing New York’s first edition of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in February 1776. By far the most influential tract of the American Revolution, the pamphlet had first been published a month previously by Robert Bell in Philadelphia.

When the British took possession of Manhattan in August 1776, the family escaped to Greenwich, Connecticut, but John lost nearly all of his books and printing materials on the way. They returned home soon after the British had departed. John Anderson would later run an auction house from his shop at 77 Wall Street.

Young Alexander Anderson took an early interest in the skill of local engravers and silversmiths. At the age of twelve years he made his first attempts at engraving on copper. By 1794 he was employed by William Durell, bookseller at 19 Queen Street, to copy the illustrations of a popular little English work entitled The Looking-Glass for the Mind.

The original images were engraved on boxwood and produced by Thomas Bewick, the pioneer of wood-engraving. Anderson soon adopted and mastered the technique.

He established himself as an artist, producing engravings for books, periodicals and newspapers. He illustrated the earliest editions of Noah Webster’s best-selling Spelling Book and millions of school children were familiar with his monogram “A.A.” in the corners of woodcuts in educational books.

In 1804 he adapted Bewick’s A General History of Quadrupeds for the American market and created forty engravings for an edition of Shakespeare. He was celebrated as “America’s First Illustrator” and “The Father of American Wood Engraving.”

Young Anderson had taken special delight in making copies of anatomical figures from medical books. It would be a lifelong passion. In 1808 he executed on wood more than sixty illustrations for an American edition of The Anatomy and Physiology of the Human Body by the Scottish anatomist Charles Bell. Medicine played a crucial part in his life and there was a time that he appeared to pursue a double career.

Scotch-Irish Patriots

After his fourteenth birthday and in spite of his passion for art, Anderson was apprenticed to the physician Joseph Young. It was a decision made for him by his parents. The idea of medicine was motivated by Alexander’s early interest in copying anatomical figures from text books, but the selection of their son’s master was significant.

John and Sarah Anderson most likely wanted him to pursue a socially useful profession in the city of New York’s independent but chaotic early development, rather than chase an individualistic career in the arts. Their Scottish identity remained strong, but they were patriots too and there was certainly a political motivation behind this choice.

Joseph Young was born in 1735 in Little Britain, Orange County, into a family of Scotch-Irish immigrants. During the 1760s he settled in Albany where he practiced medicine. In 1776 he joined the Albany Sons of Liberty and was appointed surgeon to the Ninth Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Army.

In 1778, he joined the staff of the Albany hospital. Three years later, he was promoted to hospital physician surgeon and served to the end of the war. He then removed to New York where he continued to practice medicine until his death in 1814. In their own individual ways, John Anderson and Joseph Young had been committed to the same cause.

Alexander received his license at the age at twenty. In his first year of medical practice he continued his artistic work and engraved a series of anatomical drawings on wood. In 1798 he produced a full-length and elaborate human skeleton copied from a 1747 edition of engravings by the German-born Dutch anatomist Bernard Siegfried Albinus.

Yellow Fever

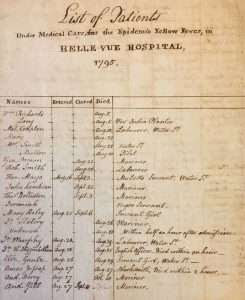

Founded in 1736, Bellevue was established by the British as an alms house. Located in the old common ground that is today City Hall Park, the second floor of the property provided six beds for the sick and insane. By 1795, it had expanded to accommodate nearly eight hundred urban paupers. That year, Anderson was appointed the institution’s first resident physician.

His immediate challenge was to deal with an outbreak of yellow fever in the city. As treatment options were limited, he witnessed many patients perish. The inability of medical staff to intervene deeply frustrated him. The burden of his task affected his mental well-being.

In his grim recollections of the epidemic, he admitted to a state of great depression. In a detailed list written in his hand, 238 yellow fever patients were admitted between August and October. One hundred and thirty-seven died.

When the epidemic ended, he sought an academic qualification to enhance his personal ability as a physician. In May 1796, at the age of twenty-one, he received the degree of Doctor of Medicine from the faculty of Columbia College. The subject of his inaugural dissertation (dedicated to Joseph Young) was “Chronic Mania.”

What motivated the young man to study this topic? Was he trying to deal with his own mental problems after the Bellevue experience?

With the city of New York’s burgeoning population and the alarming spread of contagious diseases, it became necessary to find a larger property to expand space for quarantine. In 1798 the commissioners purchased “Bel-Vue,” a parcel of land on Manhattan’s east side near Murray Hill, named for its fine view of the East River and the surrounding fields (the hospital was formally named Bellevue in 1824).

While New York Hospital on Broadway (opened in 1771) catered to high society, Bellevue became a refuge for the poor and destitute, mostly immigrants living in the slums of Lower Manhattan. Since its inception, Bellevue did not charge for treatment, acting as the hospital of last resort for the city’s most troubled inhabitants. It treated presidents and paupers alike.

When another, even more serious outbreak of yellow fever occurred in 1798 (more than 2,000 people died in the epidemic), Anderson returned to Bellevue as resident physician. He resigned a few weeks later after his three-month-old son, brother and father all died in the epidemic. His wife and mother passed soon afterwards.

These devastating losses would haunt him for the rest of his days. Emotionally drained and deeply depressed, he gave up his career as a physician and decided to devote his life to creative endeavors.

Having enjoyed a productive career as an engraver, Anderson died in January 1870. That same year the US Census Bureau recorded New York’s population at a milestone number of 942,292 citizens, affirming its status as the nation’s most populous city.

Bellevue’s ambulances were busier than ever that year, attending to 1401 emergency calls routed through the police. Anderson had been one of the pioneers who had been prepared to risk to own lives during severe epidemics in order to shield fellow New Yorkers from suffering.

CREDITS

JAN HARSKAMP

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: New York Alms House, later Bellevue Hospital (Library of Congress); Stanley Fox, “A Scene in the New York Morgue: Identification of the Unknown Dead,” wood engraving (Harper’s Weekly, July 7, 1866); an engraved self-portrait of Alexander Anderson at eighty-one; Anderson’s list of yellow fever patients, 1795 (New-York Historical Society); and the Bellevue Hospital Ambulance.

PHOTO OF THE DAY

CAN YOU IDENTIFY THE STRUCURES?

SEND TO ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment