Thursday, October 24, 2024 – RETURNED VETERANS LIVING IN SHACKS

1930’S SQUATTERS COLONY

ON

RIVERSIDE DRIVE

Thursday, October 24, 2024

EPHEMERAL NEW YORK

ISSUE #1334

The 1930s squatters colony that built its shacks beneath the luxury apartments of Riverside Drive

The Great Depression may have been a national financial catastrophe. But it hit New York City especially hard.

In 1932, three years after Wall Street crashed, one third of city workers were unemployed, and half of al factories had shut down production. An estimated 1.6 million residents relied on relief from shaky public funds and dwindling private charities.

Though Mayor Jimmy Walker’s administration launched an initiative to halt the eviction of poor families from their homes, according to New York Almanack, homeless encampments of mostly single men sprang up all over Gotham.

A shantytown called Hooverville popped up in Central Park. “Hardlucksville,” on East 10th Street, was a collection of shacks beside the East River. “Packing Box City” appeared on Houston Street. Two more Hoovervilles existed on Hester Street and on Red Hook’s Columbia Street.

And between the luxury apartment residences high up on Riverside Drive and the Hudson River below was a shanty community of 87 homeless men known as “Camp Thomas Paine.”

Why Thomas Paine? In The American Crisis from 1776, Paine wrote, “These are the times that try men’s souls”—which must have resonated in Depression-era America.

The men who lived in Camp Thomas Paine weren’t from New York City. “The Camp was initially formed in 1932 by seventy-five World War I veterans in Washington D.C.,” stated the neighborhood website I Love the Upper West Side.

After being expelled from Washington, “the group settled on Manhattan’s Upper West Side from 72nd to 79th Streets along the Hudson River,” per the website. A Daily News article from 1933 described the enclave as “in the trash flats bordering the Hudson.” (Below, an aerial view)

Riverside Drive, officially opened in 1880, was no stranger to shacks and shanties. In the Drive’s earliest decades as a budding millionaire colony, a line of palatial mansions and elegant row houses overlooking Riverside Park and the Hudson River were occasionally interrupted by flimsy wood shanties left over from the Upper West Side’s more rural, less monied era.

By the 1930s, however, the shacks as well as many of the mansions were gone. In their place rose handsome apartment houses for well-off city residents who likely didn’t anticipate a homeless commune getting in the way of their park and river views.

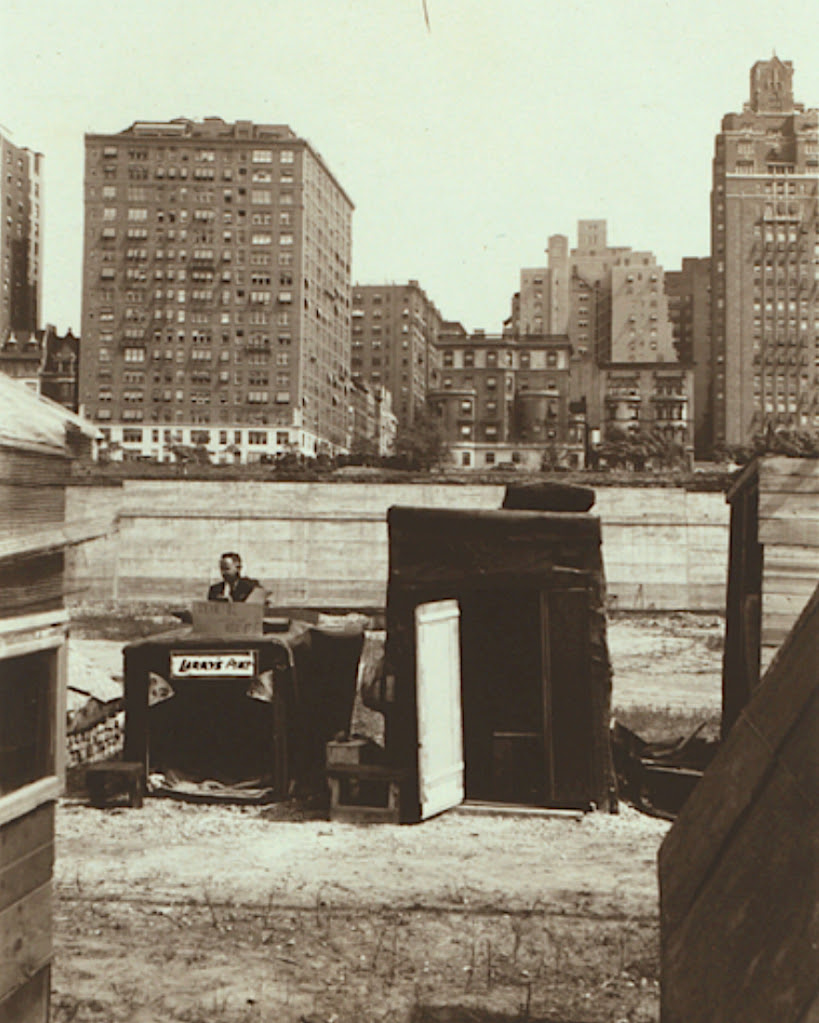

The Camp, explained a sympathetic New York Times article from 1933, is located “where the tugboats go puffing lazily up and down in the damp November fogs. On the east, freight trains clank and jar together in the night, and beyond, on a superior eminence, the politely glacial facades of Riverside Drive look down, not always approvingly.”

But Riverside Drive residents—and New York City officials—didn’t evict Camp Thomas Paine, at least not at first. Perhaps because the veterans who built their shacks there made sure the community was orderly and structured, Mayor John P. O’Brien allowed them to stay.

The only stipulation was that no more shacks could be built, per the Daily News.

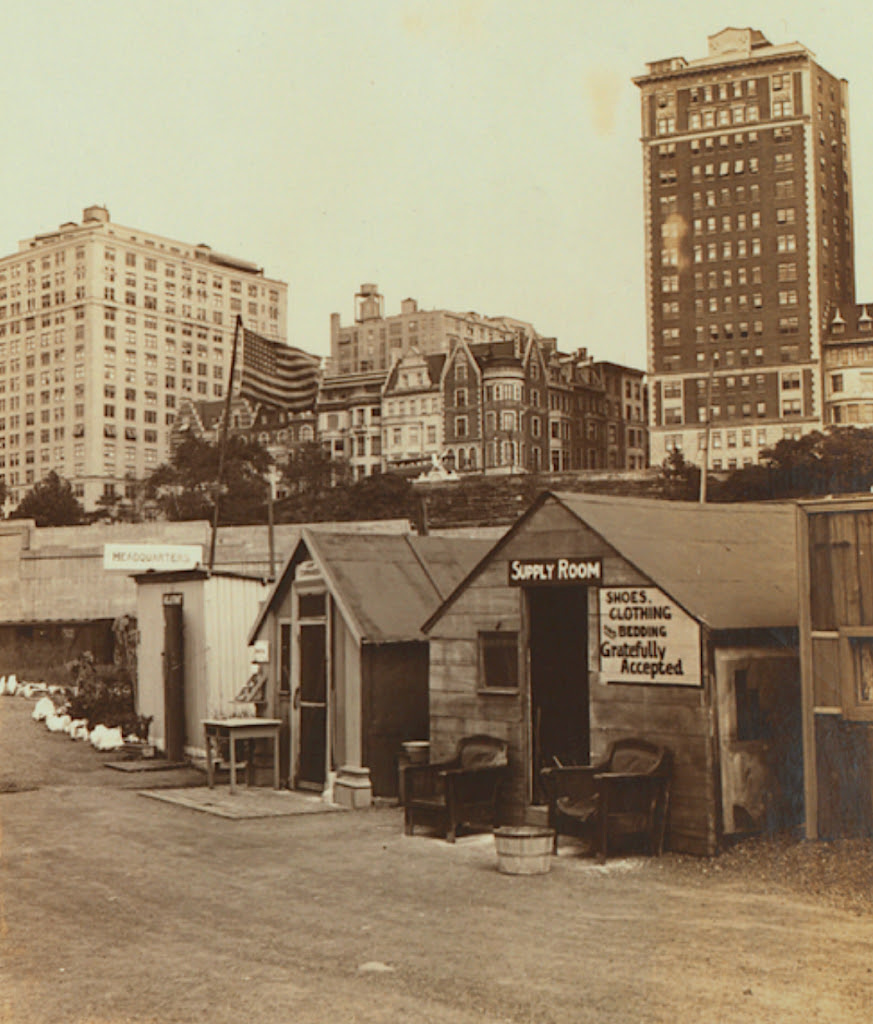

For the next few years, Riverside Drive embraced Camp Thomas Paine. The men living there occupied about 50 shacks, with the wood coming from auctioned Broadway theater sets. They ate meals at a mess hall, banned alcohol, kept a variety of pets, and accepted regular donations of food, fuel, bedding, and clothing.

“Camp Paine is not a port of missing men,” stated the Daily News. “Women come down looking for their husbands; fathers looking for sons, but no reunions have taken place. Nobody seems to be hiding there and the police never bother the men. It’s just a place where a man can call his soul his own.”

But Camp Thomas Paine’s days were numbered. In March 1934, a Daily News article reported that Robert Moses, at the time the city’s Parks Commissioner, sent eviction notices to the shacks. “They’re pre-empting public property that we are going to develop for public use,” the News quoted Moses.

Though many New Yorkers supported the men of Camp Thomas Paine—including Riverside Drive millionaire Charles Schwab, whose now-demolished French Chateau on the Drive is still considered to be New York’s largest-ever private house—the end was near.

“They are good neighbors,” Schwab, chairman of Bethlehem Steel, told the New York Times. “Some of the men came to our house to help in removing the snow last winter….When we had surplus produce from our Pennsylvania farm we were glad to share it with them. We will miss them.”

In May, the men torched their shacks. What didn’t burn was soon destroyed by Robert Moses in the name of West Side improvement, despite the Board of Aldermen ordering Moses to rescind the eviction. (Moses also put an end to the Columbia University Yacht Club at the foot of 86th Street.)

A handful of former Camp residents relocated to a farm colony in upstate New York, according to I Love the Upper West Side. The remaining men? Once the Camp was gone, they seem to have slipped anonymously into history—along with all the residents of the city’s Depression-era homeless encampments.

Curious about more stories of Riverside Drive? Join one of the year’s final walking tours led by Ephemeral New York and explore the Drive’s secrets, stories, and rich history. Space is available for the tour on Sunday, October 27, and the tour on Sunday, November 10. Click the links for more info!

[Top, second, and third images: NYPL Digital Collections; fourth image: New York Daily News; fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth images: NYPL Digital Collections]

Tags: Camp Thomas Paine 1930s New York City, Camp Thomas Paine Riverside Drive, Depression Shantytowns in New York City, Homeless Encampment Riverside Drive 1930s, Robert Moses Camp Thomas Paine, Shacks in New York City 1930s, Shantytown Riverside Drive Hudson River 1930s

Posted in Upper West Side/Morningside Hts | 9 Comments »

“They are good neighbors,” Schwab, chairman of Bethlehem Steel, told the New York Times. “Some of the men came to our house to help in removing the snow last winter….When we had surplus produce from our Pennsylvania farm we were glad to share it with them. We will miss them.”

In May, the men torched their shacks. What didn’t burn was soon destroyed by Robert Moses in the name of West Side improvement, despite the Board of Aldermen ordering Moses to rescind the eviction. (Moses also put an end to the Columbia University Yacht Club at the foot of 86th Street.)

A handful of former Camp residents relocated to a farm colony in upstate New York, according to I Love the Upper West Side. The remaining men? Once the Camp was gone, they seem to have slipped anonymously into history—along with all the residents of the city’s Depression-era homeless encampments.

PHOTO OF THE DAY

KIOSK STAFF NIGHT OUT

GLORIA HERMAN, BARBARA SPIEGEL & ELLEN JACOBY

WERE GUESTS AT THE TRIBA BENEFIT LAST EVENING!

A FUN EVENING CELEBRATING OUR COMMUNITY

CREDITS

EPHEMERAL NEW YORK

JUDITH BERDY

We invite you to become a cherished member of our RIHS community. Simply visit our website, RIHS.us, and select the ‘Membership’ option. It’s super easy to join online via PayPal. Your support plays a pivotal role in keeping the RIHS thriving. We appreciate you!

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment