Saturday, May 10, 2025 – TIME FOR SPORTS HISTORY THIS LATE SPINGTIME

The National League’s First Home Run, Hit By An Upstate New Yorker

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JUDITH BERDY

SATURDAY, MAY 10, 2025

ISSUE #1445

The National League’s First Home Run,

Hit By An Upstate New Yorker

May 2, 2025 by Phil Brown Leave a Comment

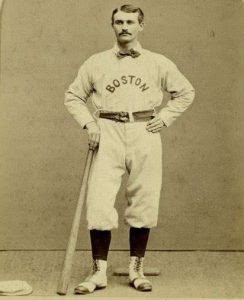

On this day in 1876, a young man from Upstate New York hit the first home run in the history of the National League. Ross Barnes, the Chicago White Stockings’ second baseman, was not known as a home-run hitter, but in the infancy of professional baseball, no one was.

The parks were spacious, and the ball was dead. Nearly all homers were inside-the-park jobs, with the batter dashing around all the bases. Hence, the term home run.

He hit the homer off Cherokee Fisher, the ace of the Cincinnati Red Stockings, in the top of the fifth inning. A sportswriter for the Chicago Tribune described the feat: “Barnes, coming to bat with two men out, made the finest hit of the game, straight down the left field to the carriages, for a clean home run.”

In the parlance of the time, a “clean home run” was one that did not involve errors or overthrows, according to the Vintage Base Ball Association. Henry Chadwick, the pioneering baseball writer, argued that only clean home runs should count as genuine home runs. In this instance, Barnes hit a ball that reached horse-drawn carriages deep in the outfield from which some spectators watched the game.

Barnes had two more hits, including a triple, as Chicago beat the Red Stockings, 15-9. Errors on both sides, not infrequent in the days before players wore gloves, accounted for much of the scoring.

About 4,000 people attended the game at Cincinnati’s Brighton Park. Barnes would hit only one other homer in 1876, which was the first year of the National League. The season’s home-run champion, George Hall of the Philadelphia Athletics, hit just five.

Barnes dominated the other offensive categories like no one before or since. He batted .429, an astounding 63 points higher than Hall, the second-place finisher. He also led the league in hits, runs, doubles, triples, walks, total bases, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage.

What’s more, Barnes led all second basemen in fielding average. He was known for his sure hands and strong, accurate throws. Decades later, old-timers who had seen Barnes in action described him as one of best to play the game. More recently, baseball historians have revived interest in Barnes and other 19th-century players. It has even been suggested that he belongs in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Charles Roscoe “Ross” Barnes was born on May 8, 1850 in Mount Morris, a small town in Livingston County, south of Rochester. Its population was about 4,500. Other notables born there include Francis Julius Bellamy, the author of the Pledge of Allegiance, and John Wesley Powell, the explorer of the Grand Canyon and the American West.

By the mid-1860s, the Barnes family had moved to Rockford, Illinois, where Ross played baseball in a youth league. Within a few years, the teenager was playing for the Rockford Forest City Club, an adult amateur team. Another local teen, Al Spalding, was the mound ace.

Rockford was one of the strongest baseball teams in the country. In 1867, Spalding pitched the Rockfords to a celebrated victory over the powerful Washington Nationals. It was the Washington team’s only loss in its tour of the Midwest.

In 1871, both Spalding and Barnes were recruited by Harry Wright to play for the Boston Red Stockings. This was the inaugural year of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, the first pro league. Wright, who managed the club and played centerfield, was one of the main organizers of the association.

The National Association lasted only five years, and Boston won four of the annual championships, thanks in no small part to Spalding and Barnes. Spalding led the league in wins every year, including 55 in 1875. In three of the seasons, Barnes hit over .400, and he twice won the batting title. Overall, he hit .388 during the league’s existence. He also excelled in the field and on the base paths.

After the poorly managed National Association folded, Barnes and Spalding joined the Chicago White Stockings in the new National League. Unlike the association, the NL was run not by the players but by businessmen. It was the brainchild of William Hulbert, president of the Chicago club. Hulbert served as the league’s president for its first six seasons.

Chicago won the first NL pennant in 1876, with Spalding getting credit for 47 of the club’s 66 victories. As noted earlier, Barnes was the league’s dominant hitter. Unfortunately, it would be his last great season. Due to illness, he played in only 22 games the following year, batting .272.

He didn’t play at all in 1878. He tried coming back with the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1879. In 77 games, he hit .266. After another year off, he signed with Boston for a final season in the majors, hitting .271.

Some historians attribute Barnes’s precipitous decline to the abolition of the fair-foul rule in the NL’s second season. Under this rule, a struck ball that landed in fair territory and then rolled foul was still in play. If a batter managed to hit a ball like this, the fielders would be hard-pressed to get to it in time to throw him out. Barnes mastered the art of the fair-foul ball.

David Nemec, a historian of 19th-century baseball, concedes that Barnes’s stats might have been hurt by the rule change, but “his abrupt deterioration in 1877 was actually rooted in a chronic illness that permanently robbed his strength.”

Bill James sees reliance on the fair-foul rule as a demerit and argues that Barnes does not belong in the Hall of Fame. “His ‘greatness’ as a player is based on his ability to do something which was eliminated from the game 125 years ago because it was perceived as cheap trickery,” he wrote in The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, published in 2001.

Yet the contemporaries of Barnes recognized that mastering the fair-foul hit required exceptional bat control. “Only the most highly skilled strikers were able to execute it with consistency,” Robert H. Schaefer writes in National Pastime, the journal of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR).

Moreover, Barnes led the NL in doubles and triples in 1876. He also led the National Association in doubles twice and triples once. Surely, not all these extra-base hits were cheap trickery.

“Far from being a one-trick pony capable only of fair-foul hits, Barnes was a complete hitter who sprayed balls to all fields as attested by countless game summaries from Boston and Chicago newspapers,” Gregory H. Wolf writes in an article for SABR.

James is on firmer ground for denying Barnes entry into the Hall of Fame when he suggests that the National Association was not a major league. For one thing, the teams followed a haphazard schedule, competing in as few as 30 games a year. As for the 1876 season, James likens the caliber of play in the early NL to Double A ball.

Barnes played in 265 games in the National Association and 234 games in the National League. Judged by today’s standards, that’s fewer than two seasons in each league. Taken together, he played the modern equivalent of three seasons – of at best Double A ball, in James’s estimation.

And yet writers and players continued to praise his skill decades after Barnes retired. Some said he was as good as Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, and Nap LaJoie. Bob Ferguson, one of his contemporaries and a longtime manager, proclaimed Barnes the “best batter and ball player that ever lived,” according to Wolf. Al Spalding, who became a sporting-goods magnate, considered Barnes the best second baseman ever.

In 2013, the Society for Baseball Research named Barnes an Overlooked 19th Century Legend. He did a lot more than hit the NL’s first home run, and though he’s not in the hall, he deserves to be remembered.

PHOTO OF THE DAY

The clock in the Steam Plant

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: Ross Barnes in 1874; a newspaper article detailing the home run; and an advertisement for the Avenue Grounds (Brighton Park) announcing its opening with a September 9, 1875 game.

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment