MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 2020 – TWO ARTISTS MARRIED TO ABSTRACTS

Monday, September 7, 2020

Our 150th Edition

ABSTRACTIONISTS FROM

THE

WPA ERA

ROSALIND

BENGELSDORF

BYRON BROWNE

ROSALIND BENGELSDORF

Rosalind Bengelsdorf, Seated Woman, 1938, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.11

One of the youngest members of the American Abstract Artists, Rosalind Bengelsdorf championed abstraction in her writings and lectures as well as in her paintings.

As a teenager, she studied at the Art Students League (1930–34) with John Steuart Curry, Raphael Soyer, Anne Goldthwaite, and George Bridgman, and then for a year at the Annot School. In 1935, she entered Hans Hofmann’s atelier as one of the many scholarship students he took on. The following year, she joined the abstract artists working on WPA murals under Burgoyne Diller’s enlightened leadership. In Hans Hofmann, Bengelsdorf found a true mentor. His dedication to the painting as an independent object matched her growing belief that the picture plane was a “living reality” of forms, energies, and colors. Like Hofmann, Bengelsdorf believed that “the shapes that compose the picture belong to nothing else but the picture.”

She had begun to analyze objects in terms of geometric form under George Bridgman at the league and subsequently at Annot. In a high school chemistry class, Bengelsdorf became fascinated with the idea that space is filled with “myriad, infinitesimal subdivisions.” She saw “the universe as a charged miracle, a vibrating orchestration of the continuous interplay of all forms of matter.” Under Hofmann, who emphasized the interrelationship of objects and the environments they occupy, these impulses merged. For Bengelsdorf, the artist’s task became the description of “not only what he sees but also what he knows of the natural internal function” of objects and the “laws of energy that govern all matter: the opposition, tension, interrelation, combination and destruction of planes in space.”

This meant that the abstract painter was studying the laws of nature, tearing it apart and then reorganizing the parts into a new creation. Despite this emphasis on formalism, Bengelsdorf also believed that abstract art played a larger function within society. She separated artistic concerns from economic ones and championed art’s potential for increasing knowledge and understanding. Satire, motion pictures, posters, and other pictorial solutions addressed some kinds of human concerns; but the larger ones — of the mind, of the possibility for order within life’s experience — these were the domain of abstraction.

In her own paintings, such as Abstraction and Seated Woman, Bengelsdorfwas concerned with these questions. Abstraction, which relates to a WPA mural (now destroyed) Bengelsdorf painted for the Central Nurses Home on Welfare Island, balances simple geometric forms through position and color. Seated Woman, which was featured in the 1939 American Abstract Artists annual exhibition, owes a clear debt to Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror (1932, Museum of Modern Art) and gives clear evidence of her belief that “energy and form are inseparable.”

After her marriage to Byron Browne in1940, and the birth of their son, Bengelsdorf turned from full-time painting to teaching, writing, and criticism. An articulate and perceptive writer, she often reviewed the exhibitions of work by her friends from the early days of the American Abstract Artists, and continued, through her writings, to champion the cause of abstract art.

They decided that there should be only “one painter in the family,” so Rosalind turned her attention to writing and teaching, only picking up a paintbrush again after her husband died in 1961 (Fraser, “Rosalind Browne, 62; Was Abstract Painter, Teacher and Historian,” New York Times, February 1979).

- Rosalind Bengelsdorf, Abstraction, 1938, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.10

- Rosalind Bengelsdorf believed that “energy and form are inseparable,” and created paintings that expressed her interest in physical science. Here, the round, cell-like shape at the bottom of the image contrasts with the rigid lines that divide the canvas. The bright primary colors and simple shapes express the artist’s wish to “tear … apart” nature into its basic forms and reconstruct the pieces into something new (Bengelsdorf, “The New Realism,” American Abstract Artists, 1938).

“[The artist’s] painting expresses the love of life, the form and color of life—a vibrating response to its powerful energy.” Bengelsdorf, “The New Realism,” American Abstract Artists, 1938

Rosalind Bengelsdorf, Cane Press, Untitled, from the portfolio American Abstract Artists, 1937, offset lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.114.3

“THE MURALS THAT NEVER WERE”

CENTRAL NURSES RESIDENCE

WELFARE ISLAND

Central Nurses’ Residence, Metropolitan Hospital, Welfare Island, 1935. Collection of the Public Design Commission of the City of New York.

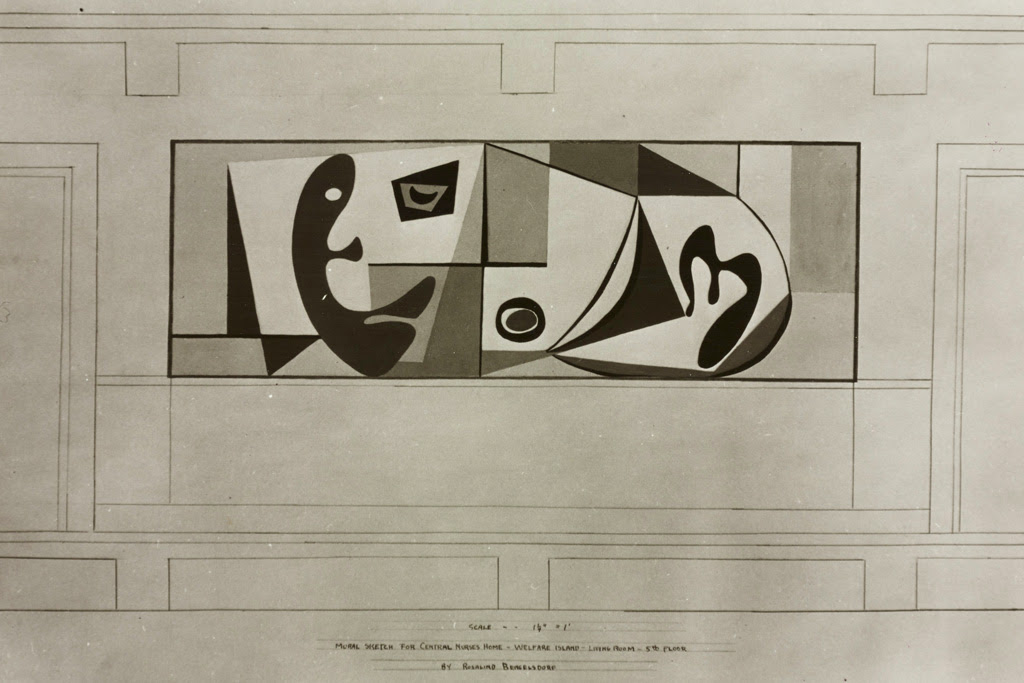

The Art Commission reviewed abstract murals by Richard Goldman and Rosalind Bengelsdorf for the Central Nurses Residence. While Richard Goldman’s mural for the fourth floor living room of the Central Nurses Residence sailed through the review process without changes, Rosalind Bengelsdorf faced difficulties with her proposal for the fifth floor living room. It was first disapproved in March 1938. A simplified proposal that included more curvilinear forms was resubmitted in June of the same year. It too was rejected. Finally in November, she offered yet another revision, much less abstract, with visual references to musical instruments and musical notes. It was approved in December 1938. Judging from the material in the Commission’s archives, this was the only abstract mural proposal that the Commission requested be altered. Perhaps not coincidentally, it was also the only submission from a female artist.

The Art Commission reviewed abstract murals by Richard Goldman and Rosalind Bengelsdorf for the Central Nurses Residence. While Richard Goldman’s mural for the fourth floor living room of the Central Nurses Residence sailed through the review process without changes, Rosalind Bengelsdorf faced difficulties with her proposal for the fifth floor living room. It was first disapproved in March 1938. A simplified proposal that included more curvilinear forms was resubmitted in June of the same year. It too was rejected. Finally in November, she offered yet another revision, much less abstract, with visual references to musical instruments and musical notes. It was approved in December 1938. Judging from the material in the Commission’s archives, this was the only abstract mural proposal that the Commission requested be altered. Perhaps not coincidentally, it was also the only submission from a female artist.

Below are the second and third submissions.

BYRON BROWNE

Byron Browne, Abstract Collage, 1933, pen and ink, ink wash, gouache, and paper on paper mounted on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.7

Modernist painter and one of the founders of American Abstract Artists, a New York City organization devoted to exhibiting abstract art. Browne specialized in still life in the style of Synthetic Cubism, influenced by his friends John Graham, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning.

Joan Stahl American Artists in Photographic Portraits from the Peter A. Juley & Son Collection (Washington, D.C. and Mineola, New York: National Museum of American Art and Dover Publications, Inc., 1995)

Byron Browne was a central figure in many of the artistic and political groups that flourished during the 1930s. He was an early member of the Artists’ Union, a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, and participated in the Artists’ Congress until 1940 when political infighting prompted Browne and others to form the break-away Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. Browne’s artistic training followed traditional lines. From 1925 to 1928, he studied at the National Academy of Design, where in his last year he won the prestigious Third Hallgarten Prize for a still-life composition. Yet before finishing his studies, Browne discovered the newly established Gallery of Living Art. There and through his friends John Graham and Arshile Gorky, he became fascinated with Picasso, Braque, Miró, and other modern masters.

The mid 1930s were difficult financially for Browne.(1) His work was exhibited in a number of shows, but sales were few. Relief came when Burgoyne Diller began championing abstraction within the WPA’s mural division. Browne completed abstract works for Studio D at radio station WNYC, the U.S. Passport Office in Rockefeller Center, the Chronic Disease Hospital, the Williamsburg Housing Project, and the 1939 World’s Fair.(2)

Although Browne destroyed his early academic work shortly after leaving the National Academy, he remained steadfast in his commitment to the value of tradition, and especially to the work of Ingres.(3) Browne believed, with his friend Gorky, that every artist has to have tradition. Without tradition art is no good. Having a tradition enables you to tackle new problems with authority, with solid footing.(4)”

Browne’s stylistic excursions took many paths during the 1930s. His WNYC mural reflects the hard-edged Neo-plastic ideas of Diller, although a rougher Expressionism better suited his fascination for the primitive, mythical, and organic. A signer, with Harari and others, of the 1937 Art Front letter, which insisted that abstract art forms “are not separated from life,” Browne admitted nature to his art—whether as an abstracted still life, a fully nonobjective canvas built from colors seen in nature, or in portraits and figure drawings executed with immaculate, Ingres-like finesse.(5) He advocated nature as the foundation for all art and had little use for the spiritual and mystical arguments promoted by Hilla Rebay at the Guggenheim Collection: When I hear the words non-objective, intra-subjective, avant-garde and such trivialities, I run. There is only visible nature, visible to the eye or, visible by mechanical means, the telescope, microscope, etc.”(6)

Increasingly in the 1940s, Browne adopted an energetic, gestural style. Painterly brushstrokes and roughly textured surfaces amplify the primordial undercurrents posed by his symbolic and mythical themes. In 1945, Browne showed with Adolph Gottlieb, William Baziotes, David Hare, Hans Hofmann, Carl Holty, Romare Bearden, and Robert Motherwell at the newly opened Samuel Kootz Gallery. When Kootz suspended business for a year in 1948, Browne began showing at Grand Central Galleries. In 1950, he joined the faculty of the Art Students League, and in 1959 he began teaching advanced painting at New York University.

1. When she met him in October 1934, Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne recalled that her future husband’s daily diet consisted of a quart of milk, a box of cornmeal, a head of lettuce, and some raisins. See Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

2. Browne was also involved with Léger’s mural project for the French Line terminal building that was canceled after officials discovered Léger’s communist sympathies. See Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

3. The abstract quality of Ingres’s work held special appeal not only for Browne, but for John Graham and Arshile Gorky. Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne remembered Gorky waving an Ingres reproduction around at the opening of the first American Abstract Artists annual exhibition and proclaiming that the French master was more “abstract” than all the work in the exhibition. See Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

4. Gorky is quoted in Melvin P. Lader, “Graham, Gorky, de Kooning and the “Ingres Revival” in America,” Arts Magazine 52, no. 7 (March 1978): 99.

5. The classical drawings, a group of which was exhibited at Washburn Gallery in 1977, show heads (often of cross-eyed women) and classically garbed and garlanded seated figures. They have important stylistic parallels to John Graham’s paintings and drawings of the period.

6. Quoted in Gail Levin, “Byron Browne in the Context of Abstract Expressionism,” Arts Magazine 59, no. 10 (Summer 1985): 129. Browne’s notebook is in the collection of his son Stephen B. Browne. Theidea of portraying matter visible through telescope or microscope parallels the fusion of scientific and artistic vision discussed by Rosalind Bengelsdorf.

Virginia M. Mecklenburg The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press for the National Museum of American Art, 1989)

Byron Browne worked at a lumberyard to pay his tuition at the National Academy of Design, where he enrolled in 1925. He was inspired by European artists such as Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró and in 1930 burned several of his realistic works as a gesture against conventional painting. He was a founder of the American Abstract Artists and in 1935 led a march protesting museums that did not collect modern work. After World War II, Browne exhibited frequently at the Kootz Gallery, which ardently supported avant-garde American artists. While abstract expressionism dominated New York’s art world, Browne’s paintings, which still showed recognizable figures and objects, failed to draw an audience. The gallery sold all of Browne’s work in a department store sale at “50% off,” dealing a heavy blow to the artist’s career. (Rogers, Byron Browne, A Seminal American Modernist, 2001)

Byron Browne, Cane Press, Untitled, from the portfolio American Abstract Artists, 1937, offset lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.114.6

Byron Browne, Head, 1938, oil on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.9

At first glance, Byron Browne’s Head appears frightening, with its menacing mouth and abstracted features. The pastel colors and the figure’s gaze, however, make it less intimidating and perhaps more human. Browne was greatly inspired by nature and felt his artwork should reflect what he saw in spite of his abstract style. The figure in Head also evokes a primitive mask. This type of mask, predominately from Africa, but also from Asia and Pre-Columbian America, was inspirational for a number of abstract artists during the first half of the twentieth century due to its simplified geometric shapes and sometimes brightly colored designs. Browne became interested in primitive masks while studying at the National Academy of Design in the 1920s. His style was also greatly shaped by European abstract artists, particularly Pablo Picasso, whose works reflected the influence of primitive masks as early as 1907.

“I sometimes paint the object more, I sometimes paint the object less, but by all means I must paint the object.” The artist, quoted in Levin, “Byron Browne: In the Context of Abstract Expressionism” (Arts Magazine, Summer 1985)

http://Byron Browne, White Still Life, 1947, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Katie and Walter C. Louchheim, 1971.6

Above: “Festival at Hamburg,” a mural study for the Hamburg, Iowa Post Office, by William Edward Lewis Bunn (1910-2009), created while he was in the New Deal’s Section of Fine Arts, 1941. According to SNAC, a collaborative enterprise that includes the National Archives and the University of California, “Wiliam Edward Lewis Bunn was a designer, muralist, and painter in Muscatine, Iowa and Ojai, Calif… During the 1930s he won commissions from the Federal Department of Fine Arts [the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Works Agency] to paint murals in public buildings throughout the Midwest. He also worked as an industrial designer for Shaeffer Pen and Cuckler Steel.” Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

FROM WNYC STUDIO

TO

NEW STATEN ISLAND COURTHOUSE

Byron Browne WNYC mural. (Photo courtesy of the Art Commission of the City of New York/FAP-WPA Photo)

Of all the artists, Byron Browne was the only one who tailored his work to fit the studio. He painted directly onto the acoustic tiles that were the soundproofing of the room. The mural (as well as the von Wicht) and some of WNYC’s Warren McArthur furniture had been used as part of 1986/87 Brooklyn Museum show The Machine Age in America, 1918-1941. Unfortunately, the mural did not return to WNYC but was moved to the city office of Management and Budget on the north side of the Municipal Building. Eventually, there were changes to those offices and the work was stored with the Art Commission of the City of New York. The mural was recently conserved and installed in the new Staten Island Courthouse.

The image of the mural was used on annual report cover.

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR ENTRY TO ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WIN A SELECT TRINKET FROM THE RIHS VISITOR CENTER KIOSK

WEEKEND PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEATING AREA BEHIND THE NEW 460 MAIN STREET

NINA LUBLIN GUESSED THE WATER CONTAINERS

USED FOR WEIGHT TESTING OF THE TRAM CABINS

Jay Jacobson came up with a unique answer to the question:

A supply of celebratory adult beverages for huge 8 day festival when retail shops on the Island are leased to merchants who understand that coming to Roosevelt Island is not merely to make money but also to provide a genuine community benefit. One of the vats is filled with sacred extra virgin olive oil.

OOPS

ON SATURDAY WE DID NOT MENTION THAT ALEXIS VILLEFANE GUESSED THE SAYRE AND FISHER BRICKS AT THE CHAPEL!!! ALEXIS IS OUR NUMBER ONE PHOTO IDENTIFIER .JAY JACOBSON NINA LUBLIN, JOAN BROOKS AND MANY OTHERS ARE DOING GREAT.

CLARIFICATION

WE ARE HAPPY TO GIVE WINNERS OF OUR DAILY PHOTO IDENTIFICATION A TRINKET FROM THE VISITOR CENTER. ONLY THE PERSON IDENTIFYING THE PHOTO FIRST WILL GET A PRIZE.

WE HAVE A SPECIAL GROUP OF ITEMS TO CHOOSE FROM.

WE CANNOT GIVE AWAY ALL OUR ITEMS,. PLEASE UNDERSTAND THAT IN THESE DIFFICULT TIMES, WE MUST LIMIT GIVE-AWAYS. THANK YOU

NEW FEATURE

FROM OUR KIOSK

GREAT STUFF FOR ALL OCCASIONS

CHANGE PURSES $5-

EDITORIAL

Start with one idea and you never know where you end up. I was looking into Rosalind Bengelsdorf and discovered she was married to to artist Byron Browne.

I had heard that Bengelsdorf had designed murals for the Central Nurses Residence. I discovered images of her three designs on the website of the Design Commission, formerly the Art Commission. You can see the images on the pages here.

We found an image of the WNYC studio on their website. Trying to find an image, we could not find one of the mural in its new home in the Staten Island courthouse. Finally, I located it on the cover of an annual report.

Without the wonderful websites and reference material. you can track down so much with your key board.

TODAY WE USED:

WIKIPEDIA

THE LIVING NEW DEAL

NYC DESIGN COMMISSION

WNYC ARCHIVES

RIHS ARCHIVES

Judith Berdy

Text by Judith Berdy Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky

for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All materials in this publication are copyrighted (c)

PHOTOS FROM JUDITH BERDY COPYRIGHT RIHS/2020 (C)

MATERIAL COPYRIGHT WIKIPEDIA, GOOGLE IMAGES, RIHS ARCHIVES AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION (C)

FOR THIS ISSUE:

SEE EDITORIAL ATTACHED

FUNDING BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDING

DISCRETIONARY FUNDING BY COUNCIL MEMBER BEN KALLOS THRU NYC DYCD

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment