Tuesday, April 28, 2020 Ward’s and Randall’s Islands

T U E S D A Y

April 28, 2020

RIHS’s 38th Issue of

Included in this Issue:

WARD’S & RANDALL’S ISLANDS

CELEBRATING ISLANDS WEEK

NORTH BROTHER

WARD’S & RANDALL’S

BEDLOE’S

HOFFMAN & SWINBURNE

GOVERNORS

Native Americans called Wards Island Tenkenas which translated to “Wild Lands” or “uninhabited place”whereas Randalls Island was called Minnehanonck. The islands were acquired by Wouter Van Twiller, Director General of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, in July 1637. The island’s first European names were Great Barent Island (Wards) and Little Barent Island (Randalls) after a Danish cowherd named Barent Jansen Blom.[9] Both islands’ names changed several times. At times Randalls was known as “Buchanan’s Island” and “Great Barn Island”, both of which were likely corruptions of Great Barent Island.

Captain John Montresor, an engineer with the British army, purchased Randalls Island in 1772. He renamed it Montresor’s Island and lived on it with his wife until the Revolutionary War forced him to deploy. During the Revolutionary War, both islands hosted military posts for the British military. The British used his island to launch amphibious attacks on Manhattan, and Montresor’s house there was burned in 1777.

He resigned his commission and returned to England in 1778, but retained ownership of the island until the British evacuated the city in 1783 and it was confiscated. Both islands gained their current names from new owners after the war. In November 1784, Jonathan Randell (or Randel) bought Randalls Island, while Jaspar Ward and Bartholomew Ward, sons of judge Stephen Ward, bought Wards. Nineteenth century The New York House of Refuge youth detention center in 1855. Although a small population had lived on Wards since as early as the 17th century, the Ward brothers developed the island more heavily by building a cotton mill and in 1807 building the first bridge to cross the East River.

The wooden drawbridge connected the island with Manhattan at 114th Street, and was paid for by Bartholomew Ward and Philip Milledolar. The bridge lasted until 1821, when it was destroyed in a storm. After the destruction of the bridge, Wards island was largely abandoned until 1840. Jonathan Randel’s heirs sold Randalls to the city in 1835 for $60,000. In the mid-19th century, both Randalls and Wards Islands, like nearby Blackwell’s Island, became home to a variety of social facilities.

Randalls housed an orphanage, poor house, burial ground for the poor, “idiot” asylum, homeopathic hospital and rest home for Civil War veterans, and was also site of the New York House of Refuge, a reform school completed in 1854 for juvenile delinquents or juveniles adjudicated as vagrants. Between 1840 and 1930, Wards island was used for: Burial of hundreds of thousands of bodies relocated from the Madison Square and Bryant Park graveyards

The State Emigrant Refuge, a hospital for sick and destitute immigrants, opened in 1847, the biggest hospital complex in the world during the 1850s The New York City Asylum for the Insane, opened around 1863 Manhattan Psychiatric Center (incorporating the Asylum for the Insane), operated by New York State when it took over the immigration and asylum buildings in 1899. With 4,400 patients, it was the largest psychiatric institution in the world. The 1920 census notes that the hospital had a total of 6,045 patients. It later became the Manhattan Psychiatric Center.

(c) Wikipedia

Little Hell Gate

Looking east from the footbridge at the mouth of the waterway toward the Triborough Bridge viaduct, 2008 Little Hell Gate was originally a natural waterway separating Randalls Island and Wards Island. The east end of Little Hell Gate opened into the Hell Gate passage of the East River, opposite Astoria, Queens. The west end of Little Hell Gate met the Harlem River across from East 116th Street, Manhattan.

At the Hell Gate Bridge, Little Hell Gate was over 1000 feet (300 m) wide. Currents were swift.

After the Triborough Bridge opened in 1936, it spurred the conversion of both islands to parkland. Soon thereafter, the city began filling in most of the passage between the two islands, in order to expand and connect the two parks. The inlet was filled in by the 1960s.

What is now called “Little Hell Gate Inlet” is the western end of what used to be Little Hell Gate, however, few traces of the eastern end of Little Hell Gate still remain: an indentation in the shoreline on the East River side indicates the former east entrance to that waterway. Today, parkland and part of the New York City Fire Department Academy (see below) occupy that area.

(c) Wikipedia

“Exterior View of the New Inebriate Asylum, Ward’s Island” Image Source: National Library of Medicine

In the late nineteenth century the belief that alcoholism could be cured by confinement led to the establishment of inebriate asylums. In 1864 judges were granted the power to commit alcoholics to asylums.

In the Textbook of Temperance (1869), Lees proclaims, “At last physiologists and statesmen have begun to acknowledge that the drinker’s appetite is a true mania and must be treated as such. Hence the establishment of ‘Inebriate Asylums’ in various parts of the States.” The Asylum on Ward’s Island was opened in 1868 by the Commissioners of Public Charities and Correction, becoming the third in New York State. In New York and its Institutions, 1609-1871 (1872), Richmond chronicles its opening,

“On the 21st of July 1868 the Asylum was formally opened to the public with appropriate services and on the 31st of December the resident physician reported 339 admissions. During 1869 1,490 were received and during 1870 1,270 more were admitted.” While most patients were transferred from the Workhouse, there were also three classes of paying patients, with voluntary attendance of some.

However, the Commissioners and the Attending Physician of the Inebriate Asylum came to agree with prevailing expert opinion that stricter confinement was necessary. Richmond explains, “The rules of the Institution were at first exceedingly mild. The patients were relieved from all irksome restraints, paroles very liberally granted and every inmate supposed intent on reformation. But this excessive kindness was subject to such continual abuse that to save the Institution from utter demoralization a stricter discipline was very properly introduced

As forcible detention came to lose favor as a means of treating alcoholism, the Inebriate Asylum closed in 1875. The buil.” ding temporarily housed the overflow of patients from the Insane Asylum, also located on Ward’s Island, before becoming the Homeopathic Hospital the same year.

The Homeopathic Hospital was renamed Metropolitan Hospital in 1894 when it moved to Blackwell’s Island, marking the beginning of Metropolitan’s affiliation with New York Homeopathic Medical College (now New York Medical College). 5

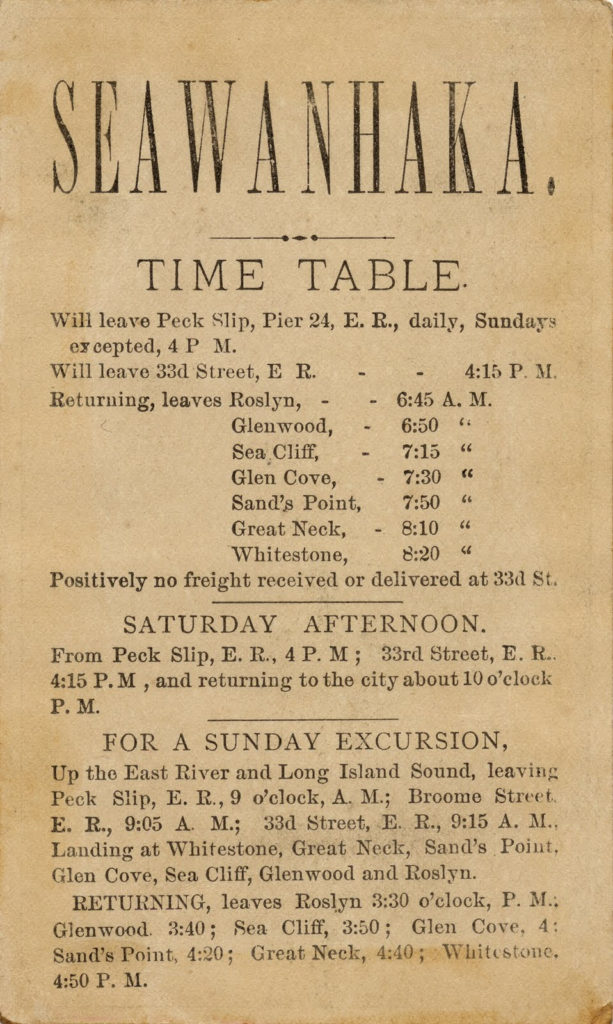

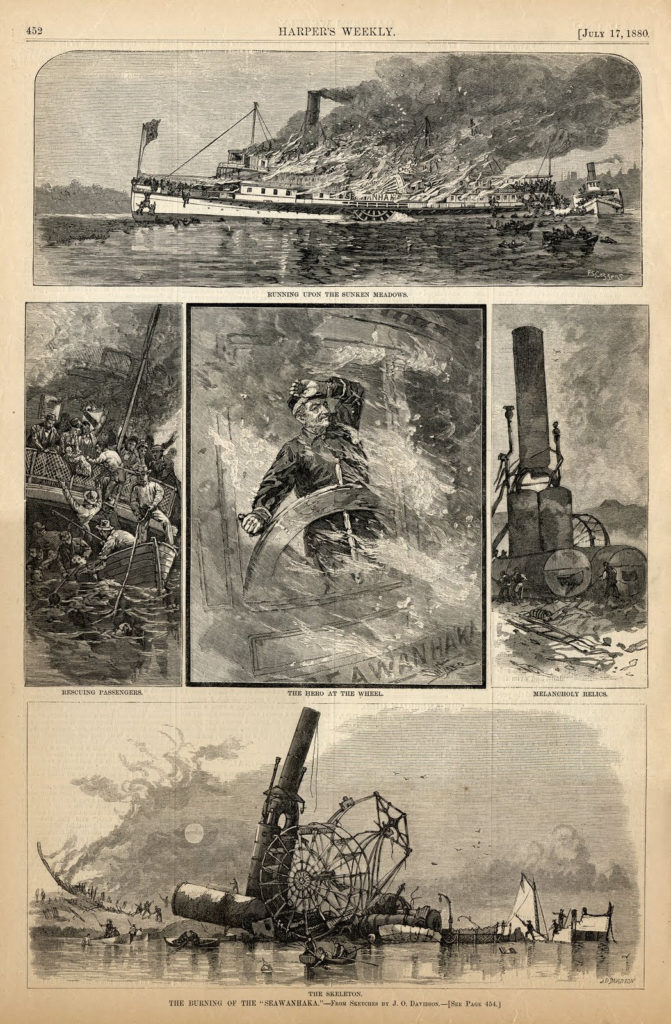

The Fire and Sinking of the Seawanhaka

EDITORIAL

I could not include all the material in today’s edition. The history that I discovered would only touch the tip of the institutional histories here. The best published source we have is Frederick Dearborn’s book “The Metropolitan Hospital: Chronicle of Sixty-two Years. Dearborn was a physician collector and wrote of the good, bad and adventures of the Homeopathic Hospital on Ward’s Island from 1875 to 1895 and after the hospital moved to Blackwell’s Island in 1895. He led the medical team that went to Mars Sur Alliers in France during World War I representing Metropolitan Hospital. This book is of great value for researchers. It includes the names of Physicians Alumni and even the nursing school graduates until the year 1936. I have often used this book to see if I can locate a graduate.

These two islands have a long and complicated history of institutional uses and buildings being used by multiple hospitals, asylums, orphanage and other facilities. I must say that the history of most of these was bleak and miserable for the patients, inmates or others confined here.

Judith Berdy

212-688-4836

917-744-3721

jbird134@aol.com

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment