Thursday, April 30, 2020 Hoffman and Swinburne Islands

THURSDAY

APRIL 30, 2020

RIHS’s 40th Issue of

BURNED OUT OF STATEN ISLAND

THE QUARANTINE ISLANDS

HOFFMAN AND SWINBURNE ISLANDS

CELEBRATING ISLANDS WEEK

NORTH BROTHER

WARD’S & RANDALL’S

BEDLOE’S

HOFFMAN & SWINBURNE

GOVERNOR’S

The Staten Island Quarantine War

The Staten Island Quarantine War was a series of attacks on the New York Marine Hospital in Staten Island—known as “the Quarantine” and at that time the largest quarantine facility in the United States—on September 1 and 2, 1858.

The attacks, perpetrated mainly by residents of Staten Island, which had not yet joined New York City, were a result of longstanding local opposition to several quarantine facilities on the island’s East Shore. During the attacks, arsonists set a large fire that completely destroyed the hospital compound.

At trial, the leaders of the attack successfully argued that they had destroyed the Quarantine in self-defense. Though there were no deaths as a direct result of the attacks, the conflict serves as an important historical case study of the use of quarantines as a first response.

Background

From 1795 to 1798, yellow fever killed thousands in New York City. In reaction, the New York City Common Council passed a quarantine law in 1799 authored by Richard Bayley, the port’s first health officer.[ This act funded the creation of the New York Marine Hospital, and the first patients arrived in 1800. Bayley died from yellow fever while caring for patients there in 1801. The Quarantine had capacity to house 1,500 patients. At its peak in the 1840s, the Quarantine treated more than 8,000 patients each year.

By the 1850s a rigorous inspection system was in place. Newly arrived ships were boarded, and if any signs of disease were found, all passengers were unloaded at the Quarantine. Health officials housed first-class passengers in St. Nicholas Hospital while passengers from steerage were put in the shanties.

The Quarantine was on a large site in the former town of Castleton, overlooking Upper New York Bay near the border of today’s St. George and Tompkinsville. The site is now occupied by the Staten Island Coast Guard Station and the National Lighthouse Museum The Quarantine comprised over a dozen buildings: Map of the Marine Hospital grounds St. Nicholas Hospital, the most-prominent structure on the site; the Smallpox Hospital, with six wards; the Female Hospital, a two-story structure; grounds buildings containing offices, harbor inspectors, and physicians’ residences; eight wooden shanties for housing patients. A six-foot-high brick wall enclosed the grounds.

The Quarantine Hospital, 1858 Opposition to the Quarantine by local residents began from its creation. In this sense, “the quarantine war” could be understood as a decades-long campaign by Staten Islanders against the facility. Land owners opposed the acquisition of the site by the city but also complained about the effects of the Quarantine on property values. “I have thought the existence of the Quarantine very injurious,” explained one land developer in 1849, “to the rise and sale of property “

Staten Islanders blamed local infectious outbreaks on the presence of the Quarantine. In addition, tensions between employees of the Quarantine and local residents grew throughout the 1850s. Attempt to establish a new quarantine facility at Seguine Point In 1857 New York City officials attempted to defuse local anger by moving the facility to a more remote location on Staten Island, Seguine Point.

However, arsonists from the town of Westfield destroyed the construction site before the new facility could be finished.[One participant in that attack wrote an anonymous letter to The New York Times, signed as “An Oysterman”, warning of further action if construction resumed: “Yes, I may say that every urchin who can rub a match will aid in producing a general conflagration of materials that shall be sent there for the purpose of erecting an institution which will endanger their lives and destroy their homes.”[

Another writer to The New York Times declared that the populace would resist the establishment of a quarantine hospital at Seguine Point even if it cost “thousands of lives”. In April 1858, arsonists destroyed the remaining buildings at Seguine Point. A combined reward of $3,000 (equivalent to $89,000 in 2019) from New York State and City officials for information about the perpetrators resulted in only one arrest.[

Resolutions of the Castleton Board of Health

In 1856 the Castleton Board of Health (located on Staten Island and sympathetic to its residents) passed an ordinance that prohibited anyone from passing from the grounds of the Quarantine into the town. From 1856 through 1858, local residents sporadically erected barricades to prevent access to the Quarantine.[

Yellow fever returned to Staten Island in August 1858. Locals were quick to blame the outbreak on workers from the Quarantine. In August 1858 the Castleton Board of Health passed ordinances encouraging local residents to take action against the Quarantine. When New York City officials sought an injunction against the Castleton Board of Health, locals responded by threatening to burn down the Quarantine. In retaliation, the City shut down the Staten Island Ferry, ostensibly on health grounds. At this point, locals began to stockpile hay and other flammable materials

On September 1, 1858, the Castleton Board of Health passed the following resolution: “[The Quarantine is] a pest and a nuisance of the most odious character, bringing death and desolation to the very doors of the people….Resolved: That this board recommend the citizens of this county to protect themselves by abating this abominable nuisance without delay.”

Attacks of September 1 and 2

Attack on the Quarantine Establishment, September 1, 1858 Attack on the Quarantine Establishment, September 1, 1858 Locals acted quickly following the passage of the Castleton Board of Health resolution. At dark, two large groups assaulted the Quarantine: one broke down the gate, the other scaled the wall on the opposite side of the compound. The attackers removed patients from buildings and then systematically used mattresses and hay to set every building on fire.]

The New York Times reported that the conflagration illuminated the bay and the entire east side of Staten Island. Efforts by employees or firemen to combat the blazes were met by violence; one stevedore was shot.[One of the leaders of the attackers, Ray Tompkins (a grandson of former Governor Daniel D. Tompkins) convinced the crowd to spare the medical staff from physical violence. In addition, Tompkins struck a deal with Quarantine staff to leave the Female Hospital standing in exchange for the release of attackers who had earlier been apprehended by Quarantine officials.

The attackers also battered down large sections of the wall surrounding the Quarantine.Two men died in the night, one from yellow fever, and one Quarantine staff member who was murdered by a co-worker. New York City officials were slow to react both because of the health risk posed by sending police officers into a quarantine zone and the likelihood of violence. The following day a handbill appeared posted throughout Tompkinsville.

The handbill read: A meeting of the Citizens of Richmond County, will be held at Nautilus Hall, Tompkinsville, this evening, September 2 at 7 1-2 o’clock , for the purpose of making arrangments to celebrate the burning of the shanties and hospitals at the Quarantine ground last evening, and to transact such business as may come before the meeting. September 2nd, 1858. Several hundred individuals attended the meeting and then proceeded to the Quarantine. The crowd burned down the Female Hospital and the piers.Government response, aftermath, and trial One hundred police officers sent by New York City arrived on September 3. They were heavily armed and even possessed an artillery piece.

The police and hospital staff moved several dozen patients who had been sheltering under makeshift tarps to Ward Island. In addition, Governor John A. King dispatched military units to Tompkinsville.[16] These forces initially consisted of several regiments of New York State militia from the 71st New York Infantry and the 7th New York Militia. The police arrested several leaders of the attack, including Ray Tompkins, on September 4.[18] At trial, the defendants argued that they had destroyed the Quarantine in self-defense. The presiding judge agreed. He noted that patients had been removed and that the local health board had previously identified the facility as a danger to the community. “For these reasons,” he concluded, “I am of opinion that no crime has been committed, that the act, the necessity of which all must deplore, was yet a necessity not caused by any act or omission of those upon whom it was imposed, and that his summary act of self-protection, justified by that necessity and therefore by law, was resorted to only after every other proper resource was exhausted.”

The historian of the conflict Kathryn Stephenson notes that the judge owned property within a mile of the Quarantine and had asked the state legislature in 1849 to remove it from Staten Island. The military occupation of Staten Island ended in early January 1859, when the new Governor of New York, Edwin D. Morgan, cancelled the orders of four companies of the 7th New York Militia which had been sent as a relief force for units that were departing Staten Island.

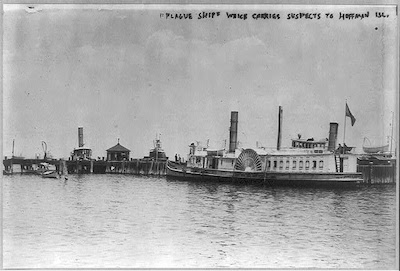

[Quarantine facilities were not re-established on the site. Instead, a floating hospital was used beginning in 1859. Two artificial islands, Swinburne Island and Hoffman Island, began operation as quarantine facilities in the 1860s.[

Swinburne Island

Hoffman Island

Hoffman Island is an 11-acre (4.5 ha) artificial island in the Lower New York Bay, off the South Beach of Staten Island, New York City. A smaller, 4-acre (1.6 ha) artificial island, Swinburne Island, lies immediately to the south.

Created in 1873 upon the Orchard Shoal[3] by the addition of landfill, the island is named for former New York City mayor (1866–1868) and New York Governor (1869–1871) John Thompson Hoffman.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Hoffman (and Swinburne) Island was used as a quarantine station, housing immigrants who, upon their arrival at the immigrant inspection station at nearby Ellis Island, presented with symptoms of contagious disease(s).World War II

Starting in 1938 and extending through World War II, the United States Merchant Marine used Hoffman and Swinburne Islands as a training station. The Quonset huts built during this period are no longer evident on Hoffman Island, but as of 2017 their remnants remain on Swinburne Island.

During World War II the islands also served as anchorages for Antisubmarine Nets intended to protect New York Bay and its associated shipping/naval activities from enemy submarines entering from the Atlantic Ocean.Post–World War II

The remains of Swinburne Island Crematorium

EDITORIAL

When I had decided to do this article I had heard of the unwelcome behavior of Staten Islanders to the facility. Reading about is is shocking. Tomorrow I will travel (by internet) to Governor’s Island. I do not know what I will find

I may add Ellis Island Coney Island and who knows what other islands in the future. Okay, I should add Bermuda, St. Thomas and Martinique!!! (I will resist Devil’s Island, since I do not speak French).

This is issue #40 and there are still more subjects to cover. That does not mean I want this quarantine to go on too long!!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment