Tuesday, August 18, 2020 – JACOB LAWRENCE STORYTELLER IN ART

TUESDAY, AUGUST 18th, 2020

The

133rd Edition

From Our Archives

JACOB LAWRENCE

ARTIST

&

“THE GREAT MIGRATION” SERIES

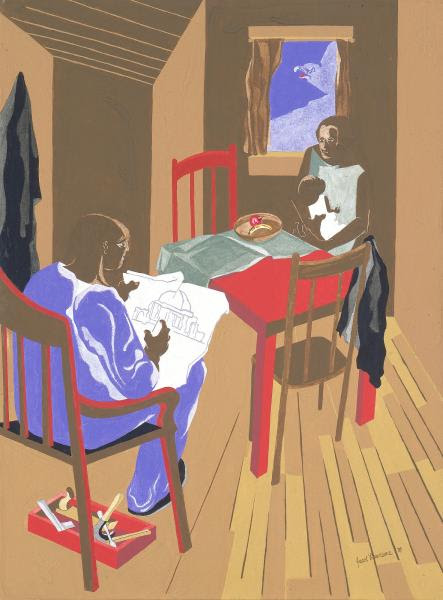

Jacob Lawrence, The Library, 1960, tempera on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc., 1969.47.24

Jacob Lawrence researched many of his paintings of African American events by reading history books and novels. Looking back at his high school years, he remembered that black culture was “never studied seriously like regular subjects,” and so he had to teach himself by visiting libraries and museums (Lawrence, 1940, Downtown Gallery Papers, Archives of American Art, quoted in Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, American Painter, 1986). This colorful view of a crowded reading room may show the 135th Street Library—now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture—where the country’s first significant collection of African American literature, history, and prints opened in 1925. Everybody appears absorbed in their books, and the standing figure in the front looking at African art may represent the artist as a young man, delving deeper into his heritage.

Jacob Lawrence, Bar and Grill, 1941, gouache on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Henry Ward Ranger through the National Academy of Design, 2010.52

In New Orleans, Lawrence experienced firsthand the daily reality of Jim Crow segregation, where legislation required that he ride in the back of city buses and live in a racially segregated neighborhood. His anger is apparent in Bar and Grill, which shows the interior of a café with a wall that divides the space into two distinct realms – one occupied by whites, the other by blacks. Lawrence says little about the individuals beyond their skin color and the way they are treated (customers on the left are cooled by a ceiling fan), but the skewed vantage point from behind the bar emphasizes the artificiality of the two separate worlds. African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era, and Beyond, 2012 Jacob Lawrence painted Bar and Grill shortly after arriving in New Orleans in late summer 1941.

Although he had just finished the sixty panels of his epic Migration series, he had only second-hand knowledge of the South, the point of origin for thousands of rural blacks who had made the great migration to industrial cities of the urban north. The South was a new experience for the young New Yorker. Lawrence’s mother had come from Virginia, his father from South Carolina, so as he remarked in 1961: “[In 1941] if you weren’t born in the South, your parents were. Your life had a whole Southern flavor; it wasn’t an alien experience to you even if you had never been there.”

Bar and Grill shows the interior of a café that is divided by a floor-to-ceiling wall that separates the commercial space into two realms—one occupied by whites, the other by blacks. Apart from obvious segregation by race, the image also reveals status. White customers drink in comfort, cooled by a ceiling fan above. The number of figures occupying each side of the room reflected the white-black ratio of city residents. Living in a southern city where legislation required that he ride in the back of city buses and live in a racially segregated neighborhood, Lawrence discovered the daily reality of Jim Crow segregation. This experience emerged in Bar and Grill and other paintings that dealt with what he called “the life of Negroes in New Orleans.” Several of Lawrence’s New Orleans paintings were featured along with a group of panels from the Migration series in a groundbreaking exhibition, Negro Art in America, which opened at Edith Gregor Halpert’s Downtown Gallery in New York City on December 8, 1941, the day the United States declared war on Germany and Japan.

The show was a huge success for Lawrence, who was celebrated by black and white critics alike. Halpert continued to push Lawrence’s work, and two years later, when Lawrence was drafted to serve as a steward in the Coast Guard, she persuaded his commanding officers to provide studio space so he could continue to paint. Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2010.

Jacob Lawrence, Firewood #55, 1942, gouache, ink and watercolor on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Information Agency through the General Services Administration, 1966.2.3

Jacob Lawrence, New Jersey, from the United States Series, 1946, watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Container Corporation of America, 1984.124.172

Jacob Lawrence was inspired by the women in his Harlem neighborhood. Like his own mother, they worked hard to support their families and survived on very little money. In this painting a girl rests on a chair in front of two large windows. In one, a tall, elegant lady stands with a bouquet of flowers and in the other, a bride and groom dance and throw confetti. Windows and doorways were focal points of New York’s brownstone neighborhoods, creating a link to life on the streets outside. But the bride and groom are clearly in a landscape beyond the city, and in this sense the windows have become screens onto which the young woman projects her fantasies. “Composing is most important. I seem to gravitate to geometric forms. It is like opening a book of geometry; I may not understand the formula but I love the beauty of line.” Lawrence, in Rago, “A Welcome from Jacob Lawrence,” School Arts, 1963

Jacob Lawrence, “In a free government, the security of civil rights must be the , 1976, opaque watercolor and pencil on paper mounted on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Container Corporation of America, 1984.124.170

Title “In a free government, the security of civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other, in the multiplicity of sects.”–James Madison, The Federalist Papers, 1788. From the series Great Ideas.

THE

GREAT MIGRATION

INTRODUCTION

WE WILL BE PRESENTING MORE VERY SOON

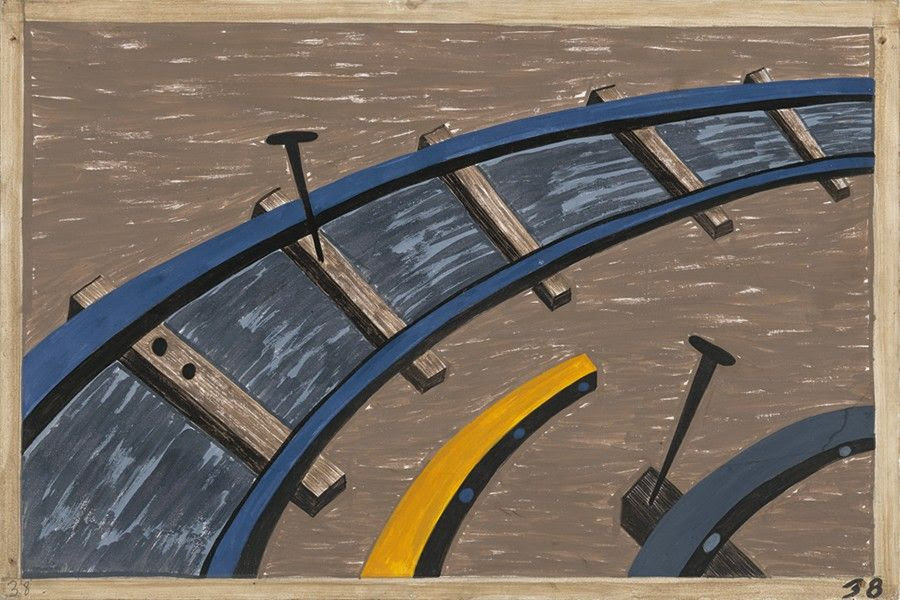

More than 75 years ago, a young artist named Jacob Lawrence set to work on an ambitious 60-panel series portraying the Great Migration, the flight of over a million African Americans from the rural South to the industrial North following the outbreak of World War I. By Lawrence’s own admission, this was a broad and complex subject to tackle in paint, one never before attempted in the visual arts. Yet, Lawrence had spent the past three years addressing similar themes of struggle, hope, triumph, and adversity in his narrative portraits on the lives of Harriet Tubman, leader of the Underground Railroad (1940), Frederick Douglass, abolitionist (1939), and Toussaint L’Ouverture, liberator of Haiti (1938). Lawrence found a way to tell his own story through the power and vibrancy of the painted image, weaving together 60 same-sized panels into one grand epic statement. Before painting the series, Lawrence researched the subject and wrote captions to accompany each panel. Like the storyboards of a film, he saw the panels as one unit, painting all 60 simultaneously, color by color, to ensure their overall visual unity. The poetry of Lawrence’s epic statement emerges from its staccato-like rhythms and repetitive symbols of movement: the train, the station, ladders, stairs, windows, and the surge of people on the move carrying bags and luggage. Following the example of the West African storyteller or griot, who spins tales of the past that have meaning for the present and the future, Lawrence tells a story that reminds us of our shared history and at the same time invites us to reflect on the universal theme of struggle in the world today: “To me, migration means movement. There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty. ‘And the migrants kept coming’ is a refrain of triumph over adversity. If it rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.”

TO SEE THE ENTIRE COLLECTION GO TO:

https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND OUR SUBMISSION TO ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WIN A KIOSK TRINKET

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

Three earthmovers that are

removing all forms of life on the east

side of Southpoint Park

WINNER #1 ALEXIS VILLEFANE

WINNER #2 JAY JACOBSON

LOSERS; ROOSEVELT ISLAND

CLARIFICATION

WE ARE HAPPY TO GIVE WINNERS OF OUR DAILY PHOTO IDENTIFICATION A TRINKET FROM THE VISITOR CENTER.

ONLY THE PERSON IDENTIFYING THE PHOTO FIRST WILL GET A PRIZE.

WE HAVE A SPECIAL GROUP OF ITEMS TO CHOOSE FROM. WE CANNOT GIVE AWAY ALL OUR ITEMS,. PLEASE UNDERSTAND THAT IN THESE DIFFICULT TIMES,

WE MUST LIMIT GIVE-AWAYS. THANK YOU

NEW FEATURE

FROM OUR KIOSK

GREAT STUFF FOR ALL OCCASIONS

LOCAL HISTORY BOOKS $25-

KIOSK IS OPEN WEEKENDS 12 NOON TO 5 P.M.

ONLINE ORDERS BY CHARGE CARD AT ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

EDITORIAL

As I have written before, our neighbors at Coler have been confined to the campus for the last six months. As with all nursing homes in New York State, no visitors are permitted and when they will be allowed it will be on a limited basis.

All group activities are severely limited and any communal event is on hold.

As the president of the Auxiliary, an organization that provides things that the home could not provide such as clothing, birthday events, parties, gardening equipment, special meals, all kinds of refreshments including coffee makers for the units and much more.

Now we need YOU to join the Auxiliary and help us become an Auxiliary member and keep activities and other services coming. The Auxiliary meets once a month and plans events, fundraisers and supports the activities that the Therapeutic Recreation Department organizes.

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment