September 26/27, 2020 – HIS FLAGS STILL BLOW IN THE BREEZE

VISIT THE RIHS BOOK SALE AND SHOP AT THE FARMER’S MARKET 9 A.M. TO 2 P.M. TODAY

SEPTEMBER 26-27, 2020

167th Edition

FREDERICK CHILDE HASSAM

BY

STEPHEN BLANK

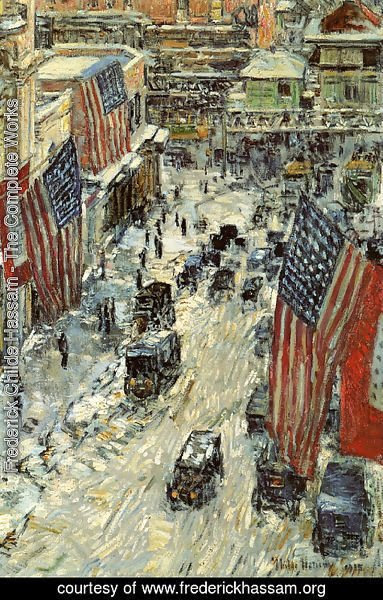

FLAGS, LOTS OF FLAGS

When I think of Childe Hassam, I think of flags. Lots of flags, flying out from buildings on 5th Avenue. But he also painted pictures of islands, in particular Appledore, the largest of the Isles of Shoals, off the Maine coast at the border with New Hampshire. It happens that Appledore Island was once named Hog Island, which was also the early name of our own Roosevelt Island (back in Dutch days). This is the only connection Hassam has to us since he didn’t paint Blackwell’s Island (that was Edward Hopper), nor, so far as I know, any pictures of hogs. But he did paint people and, most of all, landscapes, rocky coasts, and the white churches of Gloucester and East Hampton.

Childe Hassam, The South Ledges, Appledore, 1913, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.62

Childe Hassam, In the Garden (Celia Thaxter in Her Garden), 1892, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.52

A PROLIFIC ARTIST

Indeed, Childe Hassam painted a lot. Art historians say that he treated his art much like a business, aggressively marketing himself and churning out canvases and works on paper “by the carload”, and building networks of artists around him to increase his fame. He certainly seems to have been successful, building a major reputation and fortune over a career spanning more than fifty years.

Childe Hassam, The Island Garden, 1892, watercolor on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.64

Childe Hassam was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts in 1859. When his father’s business was destroyed by a fire in 1872, Hassam was forced to leave school and take a job to help support the family. The story (charming but unverified) goes that when he was fired after only three weeks in the accounting department of a publishing company, his supervisor suggested that since he spent all of his time drawing, he might consider a career in art. Taking this advice, Hassam obtained a job in a wood engraving shop, where he quickly rose to the position of draftsman. (Apparently, one of his works that he drew there, an intricate panorama of Marblehead Harbor, graced the editorial page of Marblehead’s newspaper at least until 1975, which was the most recent image I could find.) In 1882, Hassam became a free-lance illustrator, (known as a “black-and-white man” in the trade), and established his first studio. He specialized in illustrating children’s stories for magazines such as Harper’s Weekly, Scribner’s Monthly Magazine, and The Century. In that year, he had his first solo exhibition of around fifty watercolors at a Boston gallery, which included works depicting what would become one of his popular themes, landscape paintings of places he visited, such as Nantucket.

Childe Hassam, Ponte Santa Trinità, 1897, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.61

It’s not easy to classify Hassam’s work. Hassam is widely considered one of the giants of American Impressionism. He visited Paris in 1883 and sixty-seven of the watercolors (absolutely gorgeous, my opinion) he did on his trip formed the basis of his second exhibition in 1884. He married Kathleen Doan, a childhood friend, after his return to the US and they then spent several years in Paris. There’s a wonderful story (again unverified) from this time: In the summer of 1889, he rented a studio in Paris’ Montmartre district. Littering the space were unsold canvases abandoned by the previous tenant—“un peintre fou,” the concierge called him. The “mad painter” was Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The young American had never heard of the artist, a leader of the French Impressionists, but he was intrigued by his work. “I looked at these experiments in pure color and saw it was what I was trying to do myself,” he recalled 38 years later. We do know that Hassam earned a good living in Paris doing magazine illustrations and painting pictures which he sent home to dealers. They were able to find a well-located apartment/studio with a maid near the Place Pigalle, the center of the Parisian art community and lived among the French and socializing little with other American artists studying abroad.

His work shares a lot with the French impressionists, in particular his concern with the interaction of light, weather, and surface. But he seems to have been rather sensitive about his debt to French impressionists, insisting that the modern movement in painting was founded on John Constable, William Turner, and Richard Bonington. Hassam helped create a strand of Impressionism that was distinctly American. American artists, he said, were clearly able to claim a school of their own. “Inness, Whistler, Sargent and plenty of Americans just as well able to cope in their own chosen line with anything done over here…An artist should paint his own time and treat nature as he feels it, not repeat the same stupidities of his predecessors…The men who have made success today are the men who have got out of the rut.” Still, Hassam remained connected with the European Art of the 1870s and ’80s.

Hassam was unusual in the 1880s for attempting to make art out of urban streetscapes. American painting was focused then on faraway places and times. In his view, the urban scene provided its own unique atmosphere and light, one which Hassam found “capable of the most astounding effects” and as picturesque as any seaside scene. The grittiness of his urban work may also distinguish it from the work of French impressionists. His city paintings, often of pavements in the rain, were unorthodox at the time and remain much admired. During the summers, however, he would work in a more typical Impressionist location, such as Appledore Island, then famous for its artist’s colony.

Childe Hassam, The Billboards, New York, 1916, etching on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the National Museum of American History, Division of Graphic Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 1971.222

Childe Hassam, Lillie (Lillie Langtry), ca. 1898, watercolor and gouache on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.57

He and his wife returned to the US in October 1889 and settled in New York City where he helped to found the New York Water Color Club. He developed a deep friendship with fellow artists John Twachtman and J. Alden Weir over a shared affection for and desire to create Impressionist works. This focus was deepened by a friendship with Theodore Robinson, who had worked in Giverny with Claude Monet. But Hassam was drawn largely to the streets of New York. He kept a succession of studios on or near Fifth Avenue and seldom traveled more than a few blocks to paint. Sometimes he worked from a window or balcony, but often he sketched the passing crowds at street level from a parked carriage, using the opposite seat as his easel.

Feeling that the Society of American Artists was hostile to the Impressionist style they had adopted, Hassam, Twachtman and Weir left the Society in December 1897 and soon recruited seven other painters to form the Ten American Painters. The aim of The Ten was to create an exhibition society that valued their view of originality, imagination, and exhibition quality. The Ten achieved popular and critical success, and lasted two decades before dissolving.

From the late 1890s onward, Hassam’s style became even more impressionistic with quick brushstrokes that were so thin, one could almost see the canvas beneath. The increasing modernity of the city with the newly built skyscrapers, along with new summer locations he visited such as East Hampton, Long Island where Hassam would eventually buy a home, provided exciting subjects for the artist.

The outbreak of World War I was a source of inspiration late in Hassam’s career became the theme of one of Hassam’s greatest series, paintings of American and other flags that lined the many streets of New York City. Capturing the intense patriotism of the period, the works helped raise funds for the war effort while simultaneously raising the American spirit.

Childe Hassam, Noon above Newburgh, 1916, watercolor on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.59

Childe Hassam, New York Bouquet, 1917, lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the National Museum of American History, Division of Graphic Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 1971.231

Despite his emergence as one of the leaders of a new American art movement, Hassam became increasingly vocal near the end of his life against developing styles of modernism as well as European artists. He ridiculed non-representational abstraction in painting (which he called “Ellis Island paintings”) even after its acceptance as cutting-modernism by American critics in the interwar period.

An interesting character, Hassam was known for his dapper style, often wearing tweed suits and sometimes even a monocle. One art historian notes that “Hassam was a large, red-faced gentleman, proud of his New England ancestry. His life was without trials. He was lively and cheerful, rather aggressive and outgoing”, although another says he suffered from failing health and increased bouts of drinking before his death in 1935.

Hassam is viewed as a precursor in the development of a home-grown, distinctively American subject matter, who helped pave the way for other artists such as Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, and Andrew Wyeth, who, while they differed from him stylistically, shared the same commitment. On a personal note, I, like probably many of you, have seen many Childe Hassam paintings. But other than the flag series, I’m not sure I took much else seriously. Preparing this brief note for Judy opened a much wider vision of his work, particularly his wonderful work in watercolor. This has been a splendid, colorful experience and I strongly recommend his work.

Childe Hassam, Easthampton Elms in May, 1925, etching on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the National Museum of American History, Division of Graphic Arts, Smithsonian Institution, 1971.218

Childe Hassam, Tanagra (The Builders, New York), 1918, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly, 1929.6.63

WEEKEND PHOTO

SEND IN YOUR SUBMISSION

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WIN A TRINET FROM THE KIOSK SHOP

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

Steam Plant one east side of island, now in back of tram station. Jay Jacobson was the first to get it!!

Funding Provided by:

Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation Public Purpose Funds

Council Member Ben Kallos City Council Discretionary Funds thru DYCD

Text by Judith Berdy

CREDITS

https://www.frederickhassam.org/biography.html

http://hoocher.com/Frederick_Childe_Hassam/Frederick_Childe_Hassam.htm

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/hassam-childe/

http://diaryofamadinvalid.blogspot.com/2018/01/childe-hassam-american-artist.html

Edited by Deborah Dorff

ALL PHOTOS COPYRIGHT RIHS. 2020 (C)

PHOTOS IN THIS ISSUE (C) JUDITH BERDY RIHS

Thanks Stephen

Thanks to Stephen Blank for today’s feature on Childe Hassam. Enjoy the lightness and joy in his paintings. These are just a few of many that he painted. We can picture someone loved his work, knew his audience and kept everyone happy.

Judith Berdy

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment