FRIDAY, OCT. 23, 2020 – THE CITY OF PIANOS AND PIANO MAKERS

SPECIAL EDITION

THIS WEEKEND

SEND US STORIES ABOUT YOUR FAMILY CAR

“THE CARS OUR PARENTS DROVE”

DEADLINE IS FRIDAY AT 6 P.M.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23 , 2020

The

190th Edition

From Our Archives

THE SOHMER

PIANO FACTORY

&

THE ELEGANT SHOWROOMS

THAT

PROUDLY SHOWCASED

THE

INSTRUMENTS

Hugo Sohmer – founder of Sohmer & Co. – relocated his manufacturing premises from 149 East 14th Street in 1886 after building a new land-mark building on the Astoria coast of East River.

He had founded the company few years earlier together with his partner Joseph Kuder from Vienna, who was also a former Steinway and Sons employee.

The new building of Sohmer & Co was designed by Berger & Baylies architecture firm. Entering in piano building business in NY in the end of 19th century was not a hard thing to do as there were many skilled emigrants coming from Europe (mostly Germany) and the demand for the instrument was growing fast.

The building was expanded by Baylies & Co architecture firm in 1906–7. After 1924 year’s collapse of piano industry Sohmer’s production rates fell. In the time of Great Depression parts of the building were leased out to other manufacturers. However the company survived the Great Depression and maintained production in its Astoria factory till 1982 when the grand son of Hugo Sohmer sold the company to Pratt-Read company – producers of piano pieces and furniture.

The plant was then relocated to Ivoryton, Connecticut, and the building sold to Adirondack Chair Company. Between 2007 and 2013, the building was converted for residential use with new penthouse additions above the sixth floor.[5] Currently Sohmer pianos are produced in Korea.

WIKIPEDIA

Architecture

The building is one of the most prominent in the coast of Astoria on the East River. The building is specially distinguished by its mansard roofed clock tower over the top of its impressive scale. Designed by Berger & Baylies architecture firm this 6 story L-shaped factory building was a typical wealthy factory of New York’ s piano manufacturing scene. It is built in red bricks and designed in German Romanesque Revival Style or Rundbogenstil. Characteristic to this style was the usage of curved edges and surfaces on the roof. Thus segmentally-arched brick lintels. Band courses surmount the first, second and fifth floors.[7]

This factory building is one of the few surviving factories in Queens. It represents many characteristics of 19th century factory building. typically to the age these principles were always rooted in functionality and practical needs. According to architecture historian Betsy Hunter Bradly “the aesthetic bases of American Industrial building design was an ideal of beauty based on function, utility and process”.[10]

Basic characteristics of Sohmer factory – its narrow width and L-shaped plan was due to the need for natural light as the factory was built before the advent of electric lighting. The need for good light for the interior dictated the narrow shape of the floor plan, but the land plot size did not let to build it in I shaped formation. thus L-shape was chosen. Often factory buildings were in I, L, U, H, E configurations. Flat roofs were also a practical need for a factory. They were mostly used after 1860s. It was due to the fire safety.[10] Flat roofs let to eliminate the attic space – a place that could get dusty and easily catch on fire. Bricks were used for factory walls because they were the most fire resistant material.[7] Brick work decorations was a popular method of livening up large wall surfaces – displaying dogtoothing, recessed panels, channeling, pilasters, corbelling were among most popular forms of decorative brickwork.

Positioning the building on the edge of the street let the owners of the factory preserve larger back side space away from public eyes, thus buildings well organized and regular facade was the only public face of the company. The physical aesthetics played important role in marketing the company. Factory’s image was used on letterheads, catalogs, business directories and in advertisements. Typically they were bird’s eye views of the factory with smoke coming out of the chimneys thus rendering image of energy, dynamics and organization of the work.[7]

The building’s prominent location on the river front also served as an attraction of new customers. It was seen from long distances, even from across the East River. As the Sohmers were producing product for popular consumption it was important that his factory was seen by as many people as possible, thus this location served not only as a display for inhabitants of Manhattan, but also those who passed by on the boats. The building served excellent as an eye catcher because of its scale and proportions. But the most focal point of the building of course remained the clock tower elevating above the 2 wings of the factory. This clock tower remains the most significant feature of the building. It is also most elaborately decorated part of the building. Mansard roof with curved dome is covered with decorations expressing this as the most focal part of the building. From the corner side the building was seen the best thus architects have chosen to express this part of it the most. For factories usually most decorated parts were entrances and clock towers.[10]

The clock towers had their roots in cupolas of New England Mills. Clocks organized the daily lives of local community. It was long before the affordable watch had made its first appearance, when need for strictly organized daily rhythm was established. By late nineteenth century clock was one of the main tool to organize the daily lives of New Yorkers. Living synchronized was becoming a necessity. They delivered this function to the network of public clock towers, factory whistles and bells. But clock tower was more than that. it was also a fire sealed staircase for factory that prevented the fires to spread vertically in the building. Thus tower was not only aesthetically most prominent place in the factory, but also most socially important and functional one.

The clocktower that is still maintained

SOHMER PIANO SHOWROOM AT 22 STREET

The Sohmer Piano Building, or Sohmer Building, is a Neo-classical Beaux-Arts building located at 170 Fifth Avenue at East 22nd Street, in the Flatiron District neighborhood of the New York City borough of Manhattan, diagonally southwest of the Flatiron Building.

Designed by Robert Maynicke as a store-and-loft building for real-estate developer Henry Corn, and built in 1897-98 It is easily recognizable by its gold dome, which sits on top of a 2-story octagonal cupola. The building is located in within the Ladies’ Mile Historic District, and, according to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, is “characteristic of the later development phase of the District”

.It was named for the Sohmer Piano Company, which had its offices and showroom there early in the building’s history. Other tenants included architects, publishers, and merchants of leather, hats, perfume and upholstery.

SOHMER SHOWROOM AT 315 FIFTH AVENUE

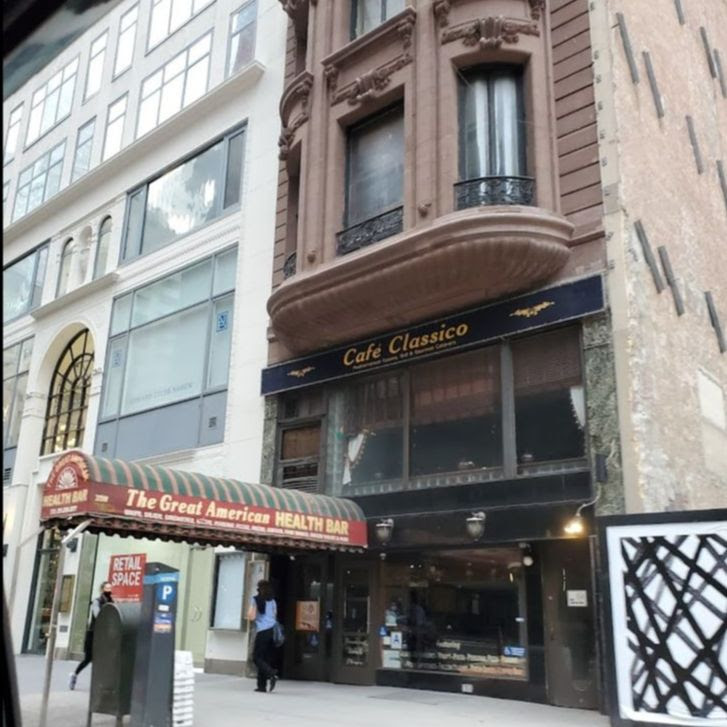

SOHMER SHOWROOM AT 31 WEST 57 STREET

31 West 57 Street Showroom

On April 4, 1911 the 68-year old millionaire died in the house following a severe stroke. His death coincided with changes that were already being noticed in the neighborhood. It had all started a decade earlier when John Jacob Astor demolished mansions at the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 55th Street for his high-end St. Regis Hotel. As millionaires avoided the encroaching commerce, fleeing northward along Central Park, their mansions were altered or razed for business buildings. The Rothschild mansion would soon join them. On November 20, 1913 The New York Times reported that Dunstan, Incorporated “one of the oldest dressmaking concerns in the city,” had taken a long-term lease on the house. The firm announced it would make “extensive alterations.” In the meantime Sohmer & Company was following the northward trend, as well. The long-established piano firm had started on 14th Street; then moved to No. 170 Fifth Avenue in 1898; then to No. 315 Fifth Avenue in July of 1909. The highly-competitive piano business in New York City kept the company’s directors constantly aware of the need to change business practices—or location. In 1919 the need to move once again was evident. Before long the piano and organ district would be centered along West 57th Street and Sohmer would be one of the pioneers in the movement. On May 3 the Real Estate Record and Guide reported that “Sohmer & Co. make the announcement that negotiations have just been completed for the leasing for a long term of years, the property at 31 West 57th Street.” It signaled the end of the line for the Rothschild residence. “The present building will be razed and there will be erected by Sohmer & Co. a six-story building, all of which will be occupied in the conduct of their piano business.” On June 7, 1919 The Music Trades reported that Harry J. Sohmer and his wife were “compelled to return to New York last Monday on account of matters pertaining to the new building now being planned by Sohmer & Co. for early erection on West Fifty-seventh Street, that required his attention. Mr. Sohmer said they were making good progress with the plans and sketches and work on the new building would be started soon.” Indeed, work got started soon. Two months later, on August 30, The Music Trades noted “Demolition of the building occupying the site of the new Sohmer structure was begun last week, and the work of construction will be pushed rapidly from this time on.” Sohmer & Co. had chosen architect Randolph H. Almiroty for its $100,000 home. “The building will have an Italian façade and will be constructed throughout with the idea of making it one of the most complete piano salons in the country,” said the Record and Guide. “The top floor will house the executive and accounting departments, both wholesale and retail.” In reporting on the planned structure, the Real Estate Record and Guide noted the changes on West 57th. “Real estate experts and those competent to know are all agreed that 57th street is destined to become one of the famous streets of the world—the ‘Bond Street’ of America.” Construction was completed within the year and Sohmer & Co. opened its doors for business in October 1920. Almiroty’s handsome Italian-inspired façade retained the proportions of the surviving former residences that surrounded it, creating a harmonious flow. The double-height, rusticated ground floor base supported four floors of understated and dignified design that demanded little attention. An 32-foot arched opening at ground floor however presented a dramatic introduction to the showrooms.

| In 1922 the two houses on either side of the Sohmer Building had been converted to businesses — photo by Wurtz Bros. from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York http://collections.mcny.org/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult_VPage&VBID=24UAYW5T4L1N&SMLS=1&RW=1366&RH=579 |

The firm’s opening announcement on October 9 said “The building was especially designed and erected” for the display of “Sohmer Pianos–Grands, Uprights, Player-Pianos–and Victor Victrolas.” “Every detail has been planned to afford a perfect environment in which to display the exquisite beauties of the Sohmer Piano.”

Before long other piano dealers would follow the lead to West 57th Street. Further west was the handsome Steinway Building which included Steinway Hall, and in 1924 the Chickering Piano firm opened its 13-story Chickering Hall next door to Sohmer & Co. at No. 29. Then in 1934 Hardman, Peck & Co. moved into the old Edward Rapallo house on the other side at No. 33 West 57th Street. Following Almiroty’s example, the street level was renovated to a similar double-height glass-paned arch.

A clever marketing scheme devised by Sohmer in 1933 was its annual National Piano Playing Tournament. School-aged pianists from New York and the vicinity entered the three-day contest, vying for national, state or district certificates of honor. The children were graded according to their excellence as compared to their age and length of time they had studied. The stark difference in the youthful attire of the 1930s and today is evident in The New York Times report on the competition on June 9, 1939. “Immaculate in starched white frocks and natty blue coats, the girls and boys, respectively–with the former outnumbering the latter by three to one–were nervous at first, but soon lost themselves in the spirit of the occasion. Although both judges and parents were forced by the rules of the tournament to sit behind screens, the players knew they were there and did their best to prove their knowledge of the piano and its part in music.” After manufacturing pianos in New York for 110 years, Sohmer & Co. moved its factory to Connecticut in 1982. The company was making at the time about 3,000 instruments per year. In announcing the move, the Sohmer management promised that the 57th Street showroom would remain. But only two years later it was gone. In December 1984 the Rizzoli International Bookstore announced its plan to move into the former Sohmer Piano Building. Like Sohmer, Rizzoli intended to use the entire building—the lower three stories being used as the main bookstore while the upper floors were reserved for imported books, stationery items and related products. Three months later the Rizzoli bookstore was opened with a grand champagne reception. Along with the facade, the firm’s architects sensitively preserved the original elegant Italian interiors. The delicate, carved-in-place plaster ceiling ornamentation was gently updated by adding a Italian fresco glaze. A few vintage fixtures from Rizzoli’s old Fifth Avenue location were integrated; including four hand-crafted chandeliers, cherry woodwork, and the hand-carved marble doorframe. Within a generation New Yorkers had forgotten that the beautiful building at No. 31 West 57th Street had not always been the Rizzoli Building. The vaulted ceilings, the old world atmosphere and the warm racks of books were as familiar to some Manhattanites as their own living room. As the 20th century came to a close, the Schieffelin mansion had lost its lower floors to be replaced by a flat-faced commercial façade; the Rapallo mansion held on to its 1930s storefront and Victorian upper floors; but the Sohmer Building was virtually intact, inside and out. By now the West 57th Street block had drastically changed and the three survivors were essentially the last relics of a far more elegant era. Then as 2013 drew to a close the LeFrak real estate family and Vornado Realty Trust, owners of the three structures, announced plans to demolish the buildings for an unspecified project. The Landmarks Preservation Commission considered the Sohmer & Co. Building and decided it “lacks the architectural significance necessary to meet the criteria for designation as an individual landmark.” The hearts of preservationists, historians, and lovers of Manhattan in general dropped. Interestingly, the three picturesque structures represent the three rapid-fire developments of the block: The Rapallo house is a surviving example of the first period of rowhouse construction; the Schieffelin mansion represents the second, fashionable period; and the Sohmer Building the commercial period. Look fast, though. It appears fairly certain that the charming buildings will not last much longer. Posted by Tom Miller at 3:27 AM Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to FacebookShare to Pinterest

I happened to drive on West 57th Street today. All that is left is 37 West. The buildings that are mentioned are only memories now.

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR ENTRY TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WIN A KIOSK TRINKET

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

The new fieldhouse in Queensbridge Park, just north of

the Queensboro Bridge.

CLARIFICATION

WE ARE HAPPY TO GIVE WINNERS OF OUR DAILY PHOTO IDENTIFICATION A TRINKET FROM THE VISITOR CENTER.

ONLY THE PERSON IDENTIFYING THE PHOTO FIRST WILL GET A PRIZE. WE HAVE A SPECIAL GROUP OF ITEMS TO CHOOSE FROM. WE CANNOT GIVE AWAY ALL OUR ITEMS,.PLEASE UNDERSTAND THAT IN THESE DIFFICULT TIMES, WE MUST LIMIT GIVE-AWAYS. THANK YOU

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

Roosevelt Island Historical Society

MATERIALS USED FROM:

WIKIPEDIA

A DAYTONIAN IN MANHATTAN (C)

NYC LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS

CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment