Weekend, January 23/24, 2021 – From the Croton Water System to your Rooftop

On Monday, January 25, a brand new Roosevelt Island branch will open at 504 Main Street. The new 5,200-square-foot location will open with grab-and-go service, and replace Roosevelt Island’s former one-room branch.

At this time, you will be able to access a small area of the branch to pick up, check out, and drop off material requested online or over the phone. Beginning today, you can use our website to request items that can be picked up from the new branch as soon as Monday; an email notification will be sent to you when your items are ready. If you prefer, you are now also able to use your phone to reserve material at this location and use contactless self-checkout when you download the new NYPL app, available for iOS and Android devices. For full details on our grab-and-go service and reopening policies, please visit our website.

The Library currently offers a wide range of free virtual programs and services to all New Yorkers. When conditions allow us to expand services, the new library will offer significantly more space for additional classes, storytimes, and computers, plus designated areas for children, teens, and adults, a community room, an outdoor seating area with an exterior book drop, and more. Learn more about our Roosevelt Island location.

The completion of this exciting project, managed by the New York City Department of Design and Construction, ensures that the Roosevelt Island Library will continue to serve New Yorkers now and in the future. The Library is thankful to Mayor Bill de Blasio, Speaker Corey Johnson, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, City Council Member Ben Kallos, NYS Assembly Member Rebecca Seawright, NYS Senator José Serrano, Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, Former Speaker Gifford Miller, Former Council Member Jessica Lappin, and the Roosevelt Island Operating Corp. for their support of this project.

Yours,

Sumie Ota

Associate Director for the East Manhattan Neighborhood Library Network

The New York Public Library

269th Edition

January 23-24, 2021

Stephen Blank

“The Wondrous Water Towers of New York City” is an art print by Pop Chart Lab featuring a “curated selection of New York City’s best rooftop darlings.”

Tanks for the Memories

If you have kept up with the reading, you will recall that the Croton Aqueduct system (and High Bridge) were completed in 1848. But that was scarcely the end of the story of water in Manhattan. Read on.

Bear in mind that a lot of things were going on in the city. Most important, New York City’s population doubled every decade from 1800 to 1880, and it expanded physically north rapidly on Manhattan Island as well. This radical growth demanded a lot of water (and, we shall see, produced a lot of water).

The Croton system brought clean water to the city, but remember that getting water into the city was one thing. Getting water into building where people lived and worked was another, and getting waste water (and other waste) out of buildings and roads was still another. These tasks were not carried out in any coherent fashion across the city, and some neighborhoods lagged badly behind.

The water towers we see on New York City roofs played an important part in the complicated evolution of our city’s water system. They have become a symbol, an icon of the city.

In 1865, New York State created a general sewage system that took into account the natural water histories of New York City districts when creating drainage lines. Unfortunately, these requirements only extended to unsewered areas; older districts would continue to struggle with sewage issues and access to clean water. Imagine the task of laying down water lines and sewer pipes in the crowded, narrow streets of much of the city.

By this time, some wealthier city households had indoor plumbing, which would have included one faucet and a water closet of some sort, but drainage systems were still in their infancy: builders buried house drains under cellar floors, rendering them inaccessible for repair or cleaning and preventing proper ventilation. If you weren’t that rich, you shared a water tap and privy in a common yard or hall. What this meant, of course, was that these districts were not only poorer but more crowded and sicker – suffering much more from typhus and small pox. Only during the 1880s, did indoor plumbing begin to appear more widely, and roughly 50 years later, top-floor storage tanks started popping up all over the city. Soon, the city mandated that every building more than 6 stories tall have a water tower.

The Tenement Act of 1901 states, “In every tenement house here after erected there shall be a separate water-closet in a separate compartment within each apartment.” Although new tenement construction had to comply and nearly all buildings erected after 1910 were built with indoor toilets, many existing tenement owners were slow to come into line with the new regulations. Indeed, in 1937, an estimated 165,000 families living in tenements were still without access to private indoor toilets.

Before we turn our attention to water tanks, let’s answer a question I know you want to ask. Before we had a comprehensive sewer system, what happened to our waste?

Well, until the late nineteenth century, most New Yorkers relied on outhouses located in backyards and alleys. While some residents had their own private outhouses, anyone living in a tenement would have shared facilities with their neighbors. The outhouse/resident ratio varied, but most tenements had just three to four outhouses and it was not uncommon to find over 100 people living in a single tenement building. This meant that people often shared a single outhouse with anywhere from 25 to 30 of their neighbors, making long line-ups and limited privacy common problems. Uncomfortable at best in the daytime and often dangerous at night. So, many continued to use chamber pots and – hopefully – empty them in outhouses and not in the street.

You cannot photograph the smell Wiki Commons

In 1975-77, I lived in a 5 story tenement on 2nd Ave at 82nd Street. Each floor had two apartments – front and back (with a window for air circulation in the dividing wall) – and a sleeping room in the hallway that would have been rented in 8-hour shifts to 3 working men. Perhaps 20 people had lived on each floor. In the hall on each floor was one toilet (and a water tap in each kitchen).

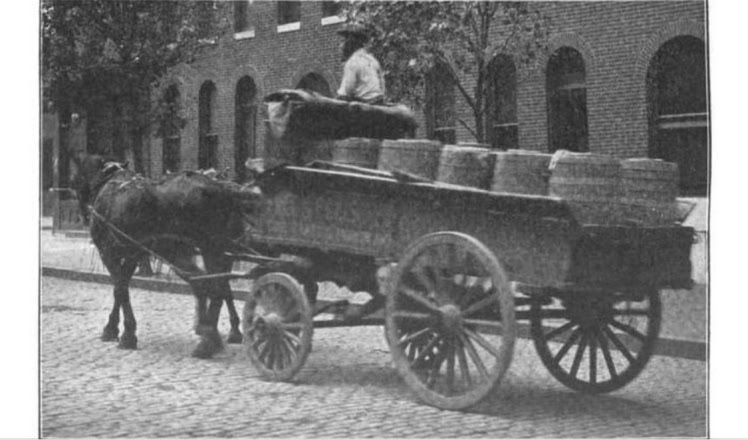

In the City, outhouses were permanent structures which meant that removing human waste was a thriving business in the nineteenth-century New York. Human waste was known as “night soil” probably because so-called night soil cart men, who worked for companies that had been lucky enough to win a coveted city contract for waste removal, made their living largely after dark. They shoveled waste from the city’s outhouses into carts (sometimes other garbage and animal carcasses would also be collected) and then disposed of the contents. Where did it go? Into the rivers, of course, and, we are told (though I am not absolutely sure of this), it was dumped on what became the UWS – which may account for some of the oddness some find there.

Even as toilets began to replace outhouses, there was still much work to be done as most cities had not yet built enough sewer pipes to connect every house. In the 1880s, two-thirds of flush toilets still emptied into backyard cesspools, which had to be cleaned to keep from overflowing. In New York, not until the first decades of the twentieth century were all toilets finally connected to main sewer lines.

In any case, water towers.

As you know, the source of New York’s water was in the Croton Highlands, considerably more elevated than the city (the water had to flow downhill in the aqueduct to reach the city). The force of this change in height (hydrostatic pressure) pushed water up to about five floors in standard multi-story buildings. But as buildings grew taller – and by the first decade of the twentieth century, much taller – the city needed a way to get water to the higher floors of buildings. One way would be to increase pressure to push water to higher levels. But this was viewed as dangerous, leading to exploding pipes. A second method, storing water in roof top tanks was viewed as a safer and cheaper alternative. Thus water tanks. Water tanks are simply giant barrels that store between 5,000 and 10,000 gallons of water which cover all uses. When the water level drops below a certain level, pumps are activated and the tanks are filled. Their design hasn’t changed substantially since they were mandated to ensure that all New York City residents had access to water.

Made of untreated wood (originally redwood, now from cedar planks) so that no chemicals or sealants will seep into drinking water, the tanks leak when first constructed until water saturates the wood, making it swell, closing any gaps between the planks held together with cable. Steel tanks are possible, but are more expensive and require more maintenance. Roof top water tanks look old, New York City antiques, but they are all pretty new. A well maintained wooden tank lasts about 25 years and then requires replacement, thus keeping the water-tower-building business alive.

When first introduced, they were used solely to provide water to the occupants of the building. After the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, buildings were required to install fire safety measures. The bottom 40% of the water in a tank is now saved for fire protection and the rest is for domestic use.

The water tanks reduce the chance that water will freeze during cold weather. It is difficult for water in a water tower to freeze if it is constantly being drained and refilled. Water can be supplied during a power failure (at least until tank needs to be refilled). Water towers provide water during peak usage times, reducing stress on the municipal water system. They are a cheaper alternative to pumps, which demand electricity and must be maintained.

Rather than roof top tanks, other systems make use water pressure tanks, which store very little water and continuously supply water at the necessary pressure by pumping. Sometimes builders hide the tanks inside elaborate structures.

Originally, water tank builders were barrel makers who expanded their craft to meet a growing need, as city buildings grew taller. Today, New York water tanks are all made by one of two local, family-owned companies — Rosenwach Tank Company and the Isseks Brothers.

The Rosenwach Tank Company, the best known of the group, first began on the Lower East Side in 1866 by barrel maker William Dalton, who later hired Polish immigrant Harris Rosenwach. After Dalton died, Rosenwach bought the company for $55 and, along with his family, expanded services over the decades to include historic building preservation, outdoor site furnishings, and new water technologies.

Rosenwach boasts that they’re the only company that mills its own quality wood tanks in New York City. Isseks Brothers opened in 1890 and is now overseen by David Hochhauser, his brother, and sister. As Scott Hochhauser told the NY Times, there has been little changes to their water tank construction process over the past century. Despite this, a lot of people are curious about the tanks. “Some are interested in the history; a lot of artists like them, for the beauty; and there are people who are into the mechanics of them. But I don’t get too many people call up to say, ‘Hey, tell me about those steel tanks.’”

Thanks for reading,

Sources

- https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/a-right-to-be-clean-sanitation-and-the-rise-of-new-york-citys-water-towers/

- https://www.6sqft.com/nyc-water-towers-history-use-and-infrastructure/#:~:text=Tanks%20were%20placed%20on%20rooftops,be%20stored%20in%20the%20tanks.

- https://www.nachi.org/commercial-water-towers.htm

- https://www.6sqft.com/stuff-you-should-know-whats-really-in-your-water-tower-and-what-to-expect-when-its-replaced/

- https://gothamist.com/news/report-some-rooftop-wooden-water-tanks-full-of-squirrel-martinis-and-other-grossness

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/when-american-cities-were-full-of-crap

- https://www.6sqft.com/life-in-new-york-city-before-indoor-toilets/

WEEKEND PHOTO

SEND IN YOUR SUBMISSION

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

FRIDAY PHOTOS OF THE DAY

SONJA HENIE

NINA LUBLIN, MARTIN DORNBAUM, GLORIA HERMAN,

LIDA FERNANDEZ, ARLENE BESSENOFF

WERE THE FIRST ONES.

SPELLING DID NOT COUNT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

Roosevelt Island Historical Society

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.

Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment