Thursday, April 29, 2021 – A building with the intention to cure never has lived up to the promise

THURSDAY, APRIL 29, 2021

The

350h Edition

Building History

The Bellevue Psychopathic

Hospital

FROM THE NYC MUNICIPAL ARCHIVES BLOG

https://www.archives.nyc/blog

Psychopathic Building, Bellevue and Allied Hospitals, architects’ rendering, 1927. Department of Public Charities and Hospitals Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Bellevue Psychopathic Hospital, as it was called at the time, was built in 1931 by Charles B. Meyers in the Italian Renaissance style. The building is still standing alongside the East River on First Avenue between 29th and 30th Streets, occupying an entire city block. When constructed, it joined the growing Bellevue hospital complex, and was intended to match the existing buildings, which were designed by architects McKim, Mead & White – same color brick, embellished with granite base course, limestone and terra cotta trimmings. By then, McKim, Mead & White was barely active; Meyers had just designed the Tammany Hall building and was a favorite of then-Mayor Jimmy Walker.

Prior to its construction, Bellevue’s mental-health facilities were part of the main hospital and included an 1879 “pavilion for the insane,” and an alcoholic ward was added in 1892. Dr. Menas Gregory, a well-known psychiatrist who spent his career working in Bellevue’s psychiatric division, is credited with the idea for a psychiatric building after a trip to inspect similar institutions in Europe – a “Temple of Mental Health,” as he called it.

Wanting to create a very clean and stately environment for the new hospital was right on brand for Dr. Gregory. In his position, he had already changed the terminology – preferring “psychopathic” to the word “insane,” thinking this would help make the patients seem curable. He had also removed the iron bars from the old pavilion’s windows and had lessened the use of narcotics and physical restraints on the patients. Dr. Gregory was seen as a good guy in the field, at a time when most medical professionals were largely ignorant about mental illness.

Psychopathic Hospital, Department of Hospitals, Charles B. Meyers, elevation, 1929, blueprint. Manhattan Building Plan Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Before the hospital was built, The New York Times said it would be “one of the finest hospitals in the world for the treatment of mental disorders” and “thoroughly modern” at a cost of $3,000,000. (Unsurprisingly, by the time it was finished, the cost would be $4,300,000 ($66,000,000 today). It was designed as a single building with three separate units: 1) 10-stories to house administrative services, doctors’ offices, labs and a library; 2) 8-stories, for mild cases; 3) 8-stories, for more advanced cases. There were facilities for recreation and occupational therapy; physio-, electro- and hydro-therapy; an out-patient clinic; teaching facilities for medical students, and a special research clinic for the study and treatment of delinquency, crime and behavior problems, in collaboration with the Department of Correction, Criminal Courts and Probation Bureau.

Bellevue Hospital complex with new psychopathic building at right, October 31, 1934. Borough President Manhattan Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Rooms were designed to house either one, two or three patients at a time. In a Mental Hygiene Bulletin, it was written that “special consideration has been given in the plans to incorporate within the building the appearance and aspect of home or normal living conditions with simple decorations and color tones believed to have the most soothing effect upon the patient.” One hundred of the six hundred beds were dedicated for the study and treatment of children, under the supervision of the Department of Education.

Completing the building was nothing short of dramatic and filled with accusations of corruption and mismanagement. Its lavish exterior juxtaposed against the great depression couldn’t have been more tone deaf to the city’s residents. When ground was broken on June 18, 1930, it was thought the building would be completed at the end of 1931. Almost a year later, in February 1931, the cornerstone was just being laid. Delays were plentiful. It reportedly took a year to choose the architect and another year to draw the plans, and then, according to the Acting Commissioner of Hospitals, “after the contractor had collected all the funds he could get, he left for Europe.”

Psychopathic Hospital, Department of Hospitals, Charles B. Meyers, first floor plan, 1929, blueprint. Manhattan Building Plan Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

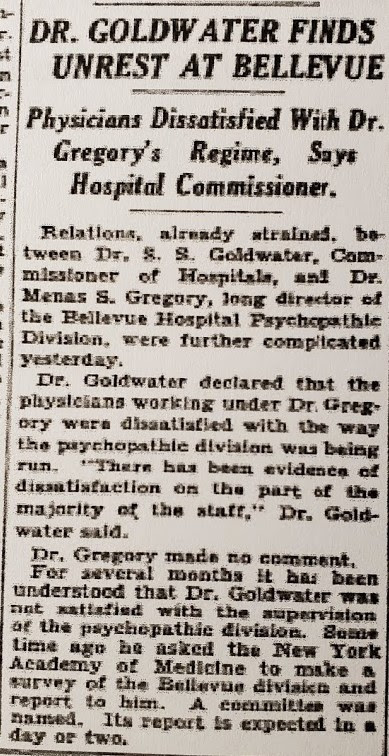

The hospital partially opened in May 1933 with the 600-bed facility only ready for 375 patients. A formal dedication occurred later that year in November, where tribute was paid to Dr. Gregory for his vision. Dr. Gregory resigned from his post in 1934, amid an investigation of his division by the Commissioner of Hospitals, Dr. S. S. Goldwater. This formed a spectacular tit-for-tat-type relationship between Dr. Gregory and Dr. Goldwater, which The New York Times covered extensively. Dr. Gregory died in 1941.

Over the years, the building went from temple of health to a scary place you didn’t want to go, and was the subject of many films, novels and exposes. The hospital saw many celebrity patients. Norman Mailer was sent there after stabbing his wife in a drunken rage. William Burroughs after he chopped off his own finger to impress someone. Eugene O’Neill had several stays in the alcoholic ward. Sylvia Plath came after a nervous breakdown. And infamous criminals like George Metesky the “Mad Bomber,” and John Lennon’s assassin, Mark David Chapman, were briefly committed to the hospital.

In 1984, the city began transitioning the building into a homeless shelter and intake center, but much of it was left empty. Around 2008, a proposal to turn the building into a hotel surfaced. To developers, the building was naturally suited to such a use, given the H-shaped layout with long hallways and small rooms.

July 20, 1934

Dr. Goldwater was the Hospital Commissioner under Mayor La Guardia

Unfortunately this building is a sad eyesore now as a neglected and homeless shelter. It is the shelter of last resort and many

attempts to renovate it have not come to fruition.

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR SUBMISSION

TO ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

The Tweed Courthouse

ED LITCHER, ARON EISENPREISS, GLORIA HERMAN,

NINA LUBLIN, NINA LUBLIN AND LAURA HUSSEY

ALL GOT IT RIGHT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Municipal Archives

NYC Department of Records

https://www.theguardian.com/food/2021/apr/06/ketchup-shortage-us-manufacturers-rush-meet-demand

https://www.thrillist.com/eat/nation/soy-sauce-packets-don-t-contain-soy-sauce

https://www.fox13news.com/news/ketchup-packets-being-sold-on-ebay-due-to-shortage

https://tedium.co/2016/01/07/condiment-sauce-packet-squeeze/

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment