Monday, September 6, 2021 – A GLIMPSE AT WORKS SHOWING OUR LABORERS AND THEIR LIVES

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2021

THE 460th EDITION

LABOR DAY

IN ART

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART

MUSEUM

THIS CAPTION IS FROM A 2014 EXHIBIT:

American Art’s exhibition Ralph Fasanella: Lest We Forget will open at the American Folk Art Museum in his home city of New York on September 2, 2014, celebrating both the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth as well as the soul of Labor Day as an American holiday of commemoration and honor. Folk and self-taught art curator, Leslie Umberger, writes about the artist and his connection to the ideas intrinsic to Labor Day.

The paintings that New Yorker Ralph Fasanella made between 1945-1995 are bold narratives of the working class. They are testaments to urban American life in the early and mid-twentieth century drawn from both personal and shared experience. Fasanella identified so strongly with the workers of America that he claimed Labor Day as his official birthday—making it known that to celebrate his life was to praise the achievements of the working class.

Fasanella’s parents immigrated to the United States in 1910 seeking a better life for their family. They were part of the immigrant wave that fueled America’s industrial age, an era when labor was cheap and plentiful and industrial practices were unregulated, unfair, and unsafe. As members of the working class became more unified, they fought for their rights with increasing success, and Fasanella learned from both his parents and his community how effective solidarity could be.

Fasanella was just fifteen years old when the stock market crashed and America was plunged into the Great Depression. To help the family get by, he took work as a delivery boy when he could find it. But the jobs never lasted and Fasanella increasingly came to believe that the Capitalist system was propelled only by greed. He became a dedicated activist, determined to fight for his rights rather than endure injustice.

The Federal holiday of Labor Day dates to 1894, but it wasn’t until 1923 that all states in the Union observed it, and in the 1930s the day meant to honor the societal contributions of the working class was reinvigorated by New Deal programs such as the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, which guaranteed the basic rights of individual workers, and the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938 which limited working hours and fixed minimum wages. Fasanella was among hundreds of thousands who joined in the annual parade meant to show the strength and spirit of the masses.

- Douglass Crockwell, Paper Workers, 1934, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.152

- The paper plant where these men are laboring was the mainstay of Glens Falls, New York, where Douglass Crockwell had his studio. Crockwell, like many artists on the Public Works of Art Project who anticipated the public exhibition of his painting, proudly depicted the chief industry of his town. The workers are smoothing and stamping an enormous roll of newsprint, the plant’s principal product.

Crockwell noted that in this scene dominated by mighty iron machinery he took “some liberties with the human form” because “the whole composition of the picture requires hard structural forms.” By showing the workers as blocky figures that appear to be roughly carved out of wood, the artist visually likened the men to the source of the wood pulp from which they made newsprint. The workers appear powerfully identified with their work. The question “what do you do for a living?” became a poignant one during this time when so many had no answer. Crockwell, a busy illustrator for much of his life, recalled that when “the depression arrived . . . there wasn’t much work.”

1934: A New Deal for Artists exhibition label

Douglass Crockwell made a massive machine the focus of this image, operated by three workers. The geometric forms and dull gray colors of the men make them appear like components in the machine, and their concentration emphasizes the determination of many Americans to overcome hardships during the Depression. The suited figure on the left, however, represents the new managerial class, who controlled the men as well as the machines. His presence emphasizes the threat to hourly workers in the 1930s, as machinery grew more sophisticated and required supervisors rather than laborers.

- Charles F. Quest, The Builders, ca. 1934-1935, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.1

- This painting shows a group of busy workers on a building site, mixing mortar, hanging cabinets, and carrying supplies. Charles F. Quest was a sculptor and printmaker as well as a painter, and enjoyed the satisfaction of making things with his hands. Here, he painted a cheerful view of construction workers that celebrates physical labor and teamwork. The thick, gritty paint evokes the sand, cement, and rough-hewn wood of an unfinished building.

- Harry Shokler, Waterfront–Brooklyn, ca. 1934, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.121

- This image shows a busy Brooklyn harbor with a view of Manhattan in the distance. Many artists during the 1930s focused on laborers and industrial scenes to emphasize the value of hard work in pulling the country out of the Depression. The smoking chimneys, groups of workers, and tracks in the snow evoke a sense of activity and perseverance in the face of hardship. To Americans in the 1930s, the skyscrapers of New York symbolized the city’s achievements and sustained the hope that the country’s economy would recover.

- Arthur Durston, Industry, 1934, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.92

- At the worst point of the Great Depression, more than fifteen million American workers were unemployed. Many who continued to work struggled to support themselves and their families. In Industry, Arthur Durston painted three dispirited women in the foreground walking away from the factories, while hunched, shirtless men toil in the background. The rooftops, pipes, towering chimney stacks, and smoke plumes appear to blend together to form one giant machine, of which the distant workers are just parts. The repetition of the women, men, and smokestacks (all are in groups of three) suggest the monotony of daily life. A newborn baby held by the most prominent woman symbolizes a hope for a better future and the ability of Americans to work through the Depression, but also a futility because the child will probably grow up to join the masses laboring in the factories.

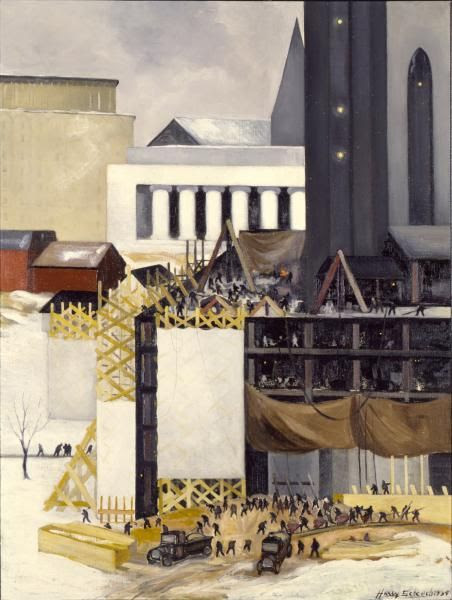

- Harry W. Scheuch, Finishing the Cathedral of Learning, 1934, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.42

- Workers scurry like busy ants to complete the University of Pittsburgh’s lofty Cathedral of Learning. The men and trucks trample the winter’s snow into mud as they labor through the frigid winter of 1933–1934 to house much-needed new classrooms. Carpenters nail timbers together to finish the scaffolding. The main part of the structure rises at the upper right, already clad in limestone blocks, while masons are still covering the lower stories of the façade in stone. Behind the Cathedral of Learning stand the gleaming white columns of the Mellon Institute Building, which was also under construction.

Artist Harry Scheuch painted the Cathedral of Learning twice for the PWAP. The first image is a close-up view of the masons at work(1964.1.157), while this second painting (1964.1.42) is a more distant view that reveals the horde of workers involved. Together the two paintings tell the story of this mighty undertaking. The forty-two-story structure was not substantially completed until 1937, and some interior work continued for decades after that. Like the Empire State Building and the Golden Gate Bridge, the Cathedral of Learning demonstrated that the Great Depression could not stop Americans from accomplishing great things.

1934: A New Deal for Artists exhibition label

Harry W. Scheuch painted this image in 1934, three years before the Cathedral of Learning at the University of Pittsburgh was finished. The cathedral was built to solve the university’s problems with overcrowding and to “convey a mood of power” to both students and residents of the city (Brown, The Cathedral of Learning, Exhibition Catalogue, 1987). The workers scurry around the base like ants, carrying equipment back and forth to the giant structure, which is the second tallest educational building in the world after Russia’s Moscow State University. The project struggled for money during the Depression, and hundreds of schoolchildren contributed dimes to “buy a brick” and help complete the work. Here, Scheuch emphasized the dramatic scale of the cathedral against the tiny workers to show what can be achieved when people work together.

Ferdinand Lo Pinto, Native’s Shack, Ketchikan, Alaska, 1937, gouache on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U. S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.210

Marcy Woods, The Oro Plata, Murphy’s Camp, California, 1934, oil on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.116

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEEKEND REMINDER

NYC Vaccine Hub – Long Island City

Wheelchair access

Community Health Center/Clinic

5-17 46th Road,**

Queens, 11101

(877) 829-4692

Vaccines offered: Pfizer (12+) Johnson & Johnson (18+) $100 incentive available

Walk-up vaccinations available to all eligible New Yorkers

FIRST DOSE APPOINTMENTS AVAILABLE!

THIS SITE IS OPEN THURSDAY THRU SUNDAY

** TWO BLOCKS FROM NYCFERRY LANDING

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment